[ed. I was subjected to one of these freeze drills in Portland, Oregon a couple years ago -- a very disorienting and eerily oppressive experience]

by Patrick Smith

At the Bangkok airport they took my scissors. This was the second time they took my scissors in Bangkok. I should have learned my lesson.

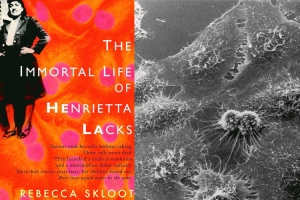

They were safety scissors, the kind you'd give to a child, about two-and-a-half inches long with rounded tips. (The photo at the top of this column shows an identical pair that I bought as a replacement.) Highly dangerous -- at least as the BKK security staff saw it. My airline pilot credentials meant nothing to them.

It's funny, but not really, when you stop to consider how easy it would be to fashion a sharp object -- certainly one deadlier than a pair of rounded-end scissors -- after boarding an airplane, from almost anything within your reach: a wine bottle, a first-class juice glass, a piece of plastic molding, and so on and so forth. Heck, if you're seated in first or business class, they give you a metal knife and fork.

But more to the point, pun intended, why do we still care so much about pointy objects?

When it came right down to it, the success of the Sept. 11 attacks had nothing -- nothing -- to do with box cutters. The hijackers could have used anything. They were not exploiting a weakness in luggage screening, but rather a weakness in our mind-set -- our understanding and expectations of what a hijacking was and how it would unfold. The hijackers weren't relying on weapons, they were relying on the element of surprise.

All of that is different now. For several reasons, from passenger awareness to armored cockpit doors, the in-flight takeover scheme has long been off the table as a viable M.O. for an attack. It was off the table before the first of the twin towers had crumbled to the ground. Why don't we see this? Although a certain anxious fixation would have been excusable in the immediate aftermath of the 2001 attacks, here it is a decade later and we're still pawing through people's bags in a hunt for what are effectively harmless items.

There in Bangkok it hit me, in a moment of gloomy clarity: These rules are never going to change, are they?

How depressing is that, to be stuck with this nonsense permanently? Not only the obsession with sharps, but the liquids and gels confiscations, the shoe removals, etc.

These policies aren't just annoying, they're potentially self-destructive. Self-destructive because they draw our security resources away from more useful pursuits. Imagine if, instead of a tiny pair of scissors, I'd had a half-pound of explosives in my luggage, shaped into some innocuous-looking item. Would the Bangkok screeners have caught it, or are they too busy hunting for pointy things and contraband shampoo? And what of passengers' checked luggage? Are the bags down below undergoing adequate scrutiny for explosives -- a far more potent threat than somebody's hobby knife?

Read more:

by Patrick Smith

At the Bangkok airport they took my scissors. This was the second time they took my scissors in Bangkok. I should have learned my lesson.

They were safety scissors, the kind you'd give to a child, about two-and-a-half inches long with rounded tips. (The photo at the top of this column shows an identical pair that I bought as a replacement.) Highly dangerous -- at least as the BKK security staff saw it. My airline pilot credentials meant nothing to them.

It's funny, but not really, when you stop to consider how easy it would be to fashion a sharp object -- certainly one deadlier than a pair of rounded-end scissors -- after boarding an airplane, from almost anything within your reach: a wine bottle, a first-class juice glass, a piece of plastic molding, and so on and so forth. Heck, if you're seated in first or business class, they give you a metal knife and fork.

But more to the point, pun intended, why do we still care so much about pointy objects?

When it came right down to it, the success of the Sept. 11 attacks had nothing -- nothing -- to do with box cutters. The hijackers could have used anything. They were not exploiting a weakness in luggage screening, but rather a weakness in our mind-set -- our understanding and expectations of what a hijacking was and how it would unfold. The hijackers weren't relying on weapons, they were relying on the element of surprise.

All of that is different now. For several reasons, from passenger awareness to armored cockpit doors, the in-flight takeover scheme has long been off the table as a viable M.O. for an attack. It was off the table before the first of the twin towers had crumbled to the ground. Why don't we see this? Although a certain anxious fixation would have been excusable in the immediate aftermath of the 2001 attacks, here it is a decade later and we're still pawing through people's bags in a hunt for what are effectively harmless items.

There in Bangkok it hit me, in a moment of gloomy clarity: These rules are never going to change, are they?

How depressing is that, to be stuck with this nonsense permanently? Not only the obsession with sharps, but the liquids and gels confiscations, the shoe removals, etc.

These policies aren't just annoying, they're potentially self-destructive. Self-destructive because they draw our security resources away from more useful pursuits. Imagine if, instead of a tiny pair of scissors, I'd had a half-pound of explosives in my luggage, shaped into some innocuous-looking item. Would the Bangkok screeners have caught it, or are they too busy hunting for pointy things and contraband shampoo? And what of passengers' checked luggage? Are the bags down below undergoing adequate scrutiny for explosives -- a far more potent threat than somebody's hobby knife?

Read more: