Saturday, August 27, 2011

Friday, August 26, 2011

Good Night, Irene

Whatever happens, here are a few tips to ride out the storm.

If you've ever wondered what total disaster preparedness looks like, here it is: http://goo.gl/kFmPL

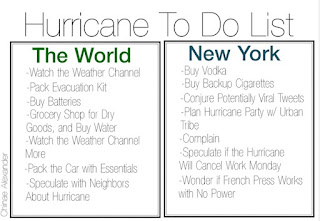

Another hurricane to-do list, this one a little more relevant to New Yorkers: http://goo.gl/7sJtD

Finally, don't take it too personally.

(Image: Taking things very personally on Van Dyke Street in Red Hook., a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share-Alike (2.0) image from Shelley Bernstein's photostream, via @adrianchen)

via:

If you've ever wondered what total disaster preparedness looks like, here it is: http://goo.gl/kFmPL

Another hurricane to-do list, this one a little more relevant to New Yorkers: http://goo.gl/7sJtD

Finally, don't take it too personally.

(Image: Taking things very personally on Van Dyke Street in Red Hook., a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share-Alike (2.0) image from Shelley Bernstein's photostream, via @adrianchen)

via:

Friday Book Club - The Road

by William Kennedy

Cormac McCarthy’s subject in his new novel is as big as it gets: the end of the civilized world, the dying of life on the planet and the spectacle of it all. He has written a visually stunning picture of how it looks at the end to two pilgrims on the road to nowhere. Color in the world — except for fire and blood — exists mainly in memory or dream. Fire and firestorms have consumed forests and cities, and from the fall of ashes and soot everything is gray, the river water black. Hydrangeas and wild orchids stand in the forest, sculptured by fire into “ashen effigies” of themselves, waiting for the wind to blow them over into dust. Intense heat has melted and tipped a city’s buildings, and window glass hangs frozen down their walls. On the Interstate “long lines of charred and rusting cars” are “sitting in a stiff gray sludge of melted rubber. ... The incinerate corpses shrunk to the size of a child and propped on the bare springs of the seats. Ten thousand dreams ensepulchred within their crozzled hearts.”

Cormac McCarthy’s subject in his new novel is as big as it gets: the end of the civilized world, the dying of life on the planet and the spectacle of it all. He has written a visually stunning picture of how it looks at the end to two pilgrims on the road to nowhere. Color in the world — except for fire and blood — exists mainly in memory or dream. Fire and firestorms have consumed forests and cities, and from the fall of ashes and soot everything is gray, the river water black. Hydrangeas and wild orchids stand in the forest, sculptured by fire into “ashen effigies” of themselves, waiting for the wind to blow them over into dust. Intense heat has melted and tipped a city’s buildings, and window glass hangs frozen down their walls. On the Interstate “long lines of charred and rusting cars” are “sitting in a stiff gray sludge of melted rubber. ... The incinerate corpses shrunk to the size of a child and propped on the bare springs of the seats. Ten thousand dreams ensepulchred within their crozzled hearts.”

McCarthy has said that death is the major issue in the world and that writers who don’t address it are not serious. Death reaches very near totality in this novel. Billions of people have died, all animal and plant life, the birds of the air and the fishes of the sea are dead: “At the tide line a woven mat of weeds and the ribs of fishes in their millions stretching along the shore as far as eye could see like an isocline of death.” Forest fires are still being ignited (by lightning? other fires?) after what seems to be a decade since that early morning — 1:17 a.m., no day, month or year specified — when the sky opened with “a long shear of light and then a series of low concussions.” The survivors (not many) of the barbaric wars that followed the event wear masks against the perpetual cloud of soot in the air. Bloodcults are consuming one another. Cannibalism became a major enterprise after the food gave out. Deranged chanting became the music of the new age.

A man in his late 40’s and his son, about 10, both unnamed, are walking a desolated road. Perhaps it is the fall, but the soot has blocked out the sun, probably everywhere on the globe, and it is snowing, very cold, and getting colder. The man and boy cannot survive another winter and are heading to the Gulf Coast for warmth, on the road to a mountain pass — unnamed, but probably Lookout Mountain on the Tennessee-Georgia border. It is through the voice of the father that McCarthy delivers his vision of end times. The son, born after the sky opened, has no memory of the world that was. His father gave him lessons about it but then stopped: “He could not enkindle in the heart of the child what was ashes in his own.” The boy’s mother committed suicide rather than face starvation, rape and the cannibalizing of herself and the family, and she mocks her husband for going forward. But he is a man with a mission. When he shoots a thug who tries to murder the boy (their first spoken contact with another human in a year) he tells his son: “My job is to take care of you. I was appointed to do that by God. I will kill anyone who touches you.” And when he washes the thug’s brains out of his son’s hair he ruminates: “All of this like some ancient anointing. So be it. Evoke the forms. Where you’ve nothing else construct ceremonies out of the air and breathe upon them.” He strokes the boy’s head and thinks: “Golden chalice, good to house a god.”

McCarthy does not say how or when God entered this man’s being and his son’s, nor does he say how or why they were chosen to survive together for 10 years, to be among the last living creatures on the road. The man believes the world is finished and that he and the boy are “two hunted animals trembling like groundfoxes in their cover. Borrowed time and borrowed world and borrowed eyes with which to sorrow it.” But the man is a zealot, pushing himself and the boy to the edge of death to achieve their unspecified destination, persisting beyond will in a drive that is instinctual, or primordial, and bewildering to himself. But the tale is as biblical as it is ultimate, and the man implies that the end has happened through godly fanaticism. The world is in a nuclear winter, though that phrase is never used. The lone allusion to our long-prophesied holy war with its attendant nukes is when the man thinks: “On this road there are no godspoke men. They are gone and I am left and they have taken with them the world.”

Read more:

image credit:

Cormac McCarthy’s subject in his new novel is as big as it gets: the end of the civilized world, the dying of life on the planet and the spectacle of it all. He has written a visually stunning picture of how it looks at the end to two pilgrims on the road to nowhere. Color in the world — except for fire and blood — exists mainly in memory or dream. Fire and firestorms have consumed forests and cities, and from the fall of ashes and soot everything is gray, the river water black. Hydrangeas and wild orchids stand in the forest, sculptured by fire into “ashen effigies” of themselves, waiting for the wind to blow them over into dust. Intense heat has melted and tipped a city’s buildings, and window glass hangs frozen down their walls. On the Interstate “long lines of charred and rusting cars” are “sitting in a stiff gray sludge of melted rubber. ... The incinerate corpses shrunk to the size of a child and propped on the bare springs of the seats. Ten thousand dreams ensepulchred within their crozzled hearts.”

Cormac McCarthy’s subject in his new novel is as big as it gets: the end of the civilized world, the dying of life on the planet and the spectacle of it all. He has written a visually stunning picture of how it looks at the end to two pilgrims on the road to nowhere. Color in the world — except for fire and blood — exists mainly in memory or dream. Fire and firestorms have consumed forests and cities, and from the fall of ashes and soot everything is gray, the river water black. Hydrangeas and wild orchids stand in the forest, sculptured by fire into “ashen effigies” of themselves, waiting for the wind to blow them over into dust. Intense heat has melted and tipped a city’s buildings, and window glass hangs frozen down their walls. On the Interstate “long lines of charred and rusting cars” are “sitting in a stiff gray sludge of melted rubber. ... The incinerate corpses shrunk to the size of a child and propped on the bare springs of the seats. Ten thousand dreams ensepulchred within their crozzled hearts.” McCarthy has said that death is the major issue in the world and that writers who don’t address it are not serious. Death reaches very near totality in this novel. Billions of people have died, all animal and plant life, the birds of the air and the fishes of the sea are dead: “At the tide line a woven mat of weeds and the ribs of fishes in their millions stretching along the shore as far as eye could see like an isocline of death.” Forest fires are still being ignited (by lightning? other fires?) after what seems to be a decade since that early morning — 1:17 a.m., no day, month or year specified — when the sky opened with “a long shear of light and then a series of low concussions.” The survivors (not many) of the barbaric wars that followed the event wear masks against the perpetual cloud of soot in the air. Bloodcults are consuming one another. Cannibalism became a major enterprise after the food gave out. Deranged chanting became the music of the new age.

A man in his late 40’s and his son, about 10, both unnamed, are walking a desolated road. Perhaps it is the fall, but the soot has blocked out the sun, probably everywhere on the globe, and it is snowing, very cold, and getting colder. The man and boy cannot survive another winter and are heading to the Gulf Coast for warmth, on the road to a mountain pass — unnamed, but probably Lookout Mountain on the Tennessee-Georgia border. It is through the voice of the father that McCarthy delivers his vision of end times. The son, born after the sky opened, has no memory of the world that was. His father gave him lessons about it but then stopped: “He could not enkindle in the heart of the child what was ashes in his own.” The boy’s mother committed suicide rather than face starvation, rape and the cannibalizing of herself and the family, and she mocks her husband for going forward. But he is a man with a mission. When he shoots a thug who tries to murder the boy (their first spoken contact with another human in a year) he tells his son: “My job is to take care of you. I was appointed to do that by God. I will kill anyone who touches you.” And when he washes the thug’s brains out of his son’s hair he ruminates: “All of this like some ancient anointing. So be it. Evoke the forms. Where you’ve nothing else construct ceremonies out of the air and breathe upon them.” He strokes the boy’s head and thinks: “Golden chalice, good to house a god.”

McCarthy does not say how or when God entered this man’s being and his son’s, nor does he say how or why they were chosen to survive together for 10 years, to be among the last living creatures on the road. The man believes the world is finished and that he and the boy are “two hunted animals trembling like groundfoxes in their cover. Borrowed time and borrowed world and borrowed eyes with which to sorrow it.” But the man is a zealot, pushing himself and the boy to the edge of death to achieve their unspecified destination, persisting beyond will in a drive that is instinctual, or primordial, and bewildering to himself. But the tale is as biblical as it is ultimate, and the man implies that the end has happened through godly fanaticism. The world is in a nuclear winter, though that phrase is never used. The lone allusion to our long-prophesied holy war with its attendant nukes is when the man thinks: “On this road there are no godspoke men. They are gone and I am left and they have taken with them the world.”

Read more:

image credit:

The Decemberists

Michael Schur, the co-creator of NBC’s Parks and Recreation, has had a long-running fascination with David Foster Wallace’s sprawling magnum opus, Infinite Jest. So when his favorite band, The Decemberists, asked him to shoot a video for their new track “Calamity Song,” he knew the creative direction he wanted to take. And so here it is — the newly-premiered video that makes “Eschaton” its creative focus. Fans of DWF’s novel will remember that Eschaton — “basically, a global thermonuclear crisis recreated on a tennis court” — appears on/around page 325. The New York Times has more…

via:

Kind of Screwed

[ed. I hate to keep harping on this, but copyright law and the concept of fair use in this digital age is a mess. I firmly believe that many transformative and aggregative efforts actually benefit copyright holders by promoting wider awareness and appreciation of their work; yet, studies examining this effect are relatively few. In the mean time, copyright opportunists (and their lawyers) continue to work off an old template and exploit this confusion by attempting to extract as many dollars as they can from people who are some of their most ardent admirers.]

by Andy Baio

The Long Version

Remember Kind of Bloop, the chiptune tribute to Miles Davis' Kind of Blue that I produced? I went out of my way to make sure the entire project was above board, licensing all the cover songs from Miles Davis's publisher and giving the total profits from the Kickstarter fundraiser to the five musicians that participated.

But there was one thing I never thought would be an issue: the cover art.

Before the project launched, I knew exactly what I wanted for the cover — a pixel art recreation of the original album cover, the only thing that made sense for an 8-bit tribute to Kind of Blue. I tried to draw it myself, but if you've ever attempted pixel art, you know how demanding it is. After several failed attempts, I asked a talented friend to do it.

You can see the results below, with the original album cover for comparison.

Original photo © Jay Maisel. Low-resolution images used for critical commentary qualifies as fair use. (Usually! Sometimes!)

In February 2010, I was contacted by attorneys representing famed New York photographer Jay Maisel, the photographer who shot the original photo of Miles Davis used for the cover of Kind of Blue.

In their demand letter, they alleged that I was infringing on Maisel's copyright by using the illustration on the album and elsewhere, as well as using the original cover in a "thank you" video I made for the album's release. In compensation, they were seeking "either statutory damages up to $150,000 for each infringement at the jury's discretion and reasonable attorneys fees or actual damages and all profits attributed to the unlicensed use of his photograph, and $25,000 for Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) violations."

After seven months of legal wrangling, we reached a settlement. Last September, I paid Maisel a sum of $32,500 and I'm unable to use the artwork again. (On the plus side, if you have a copy, it's now a collector's item!) I'm not exactly thrilled with this outcome, but I'm relieved it's over.

But this is important: the fact that I settled is not an admission of guilt. My lawyers and I firmly believe that the pixel art is "fair use" and Maisel and his counsel firmly disagree. I settled for one reason: this was the least expensive option available.

At the heart of this settlement is a debate that's been going on for decades, playing out between artists and copyright holders in and out of the courts. In particular, I think this settlement raises some interesting issues about the state of copyright for anyone involved in digital reinterpretations of copyrighted works.

Fair Use?

French street artist Invader recreates Joel Brodsky's iconic Jim Morrison photo with Rubik's Cubes

There are a lot of myths and misconceptions about "fair use" on the Internet. Everyone thinks they know what fair use is, but not even attorneys, judges, and juries can agree on a clear definition. The doctrine itself, first introduced in the 1976 Copyright Act, is frustratingly vague and continually being reinterpreted.

Four main factors come into play:

- The purpose and character of your use: Was the material transformed into something new or copied verbatim? Also, was it for commercial or educational use?

- The nature of the copyrighted work

- The amount and substantiality of the portion taken, and

- The effect of the use upon the potential market

Why Math Education Needs to Adapt to the Real World

"When am I ever going to use this?"

Chances are you've asked a math teacher that question. Maybe the teacher told you about a few real-world applications of the law of cosines, but if you're not working as a mathematician or engineer, you probably haven't thought about it since you last closed your trigonometry book. On the other hand, your job very likely requires you to know how to analyze data and statistics, or do basic finance and accounting. An op-ed in The New York Times argues that math education must adapt to reflect the practical ways we actually use it to solve real-world problems.

Sol Garfunkel, executive director of the Consortium for Mathematics and Its Applications and David Mumford, emeritus professor of mathematics at Brown, argue that instead of teaching each student the same sequence of algebra, geometry and calculus courses, those should be replaced with practical, skills-based math classes in finance, data and basic engineering. "In the data course, students would gather their own data sets and learn how, in fields as diverse as sports and medicine, larger samples give better estimates of averages," they offer as an example.

So does that mean students should be put on two different kinds of math education tracks—one for students that plan to enter STEM fields, and one for everyone else? Not necessarily; all students need to learn some of the more abstract mathematical concepts too. There needs to be a place for both "useable knowledge and abstract skills," the authors conclude.

If our math curricula actually creatively connected students to the "why" through project-based learning or teaching real-life applications (for example, using taxes to teach calculus), students would remember much more of what they learned in class. Everyone—including students who go on to become scientists, engineers and mathematicians—would gain a deeper understanding of how math applies to the world, while also being able to comprehend the federal budget.

If we don't make the switch to grounding math in the real world, we're just setting ourselves up for another generation of students who will keep asking when they'll ever use what's being taught. With no concrete answer from their teachers, they'll keep tuning out of class.

via:

photo (cc) via Flickr user lexicon10055805

TED: How Algorithms Shape Our World

via:

Cosmic Bling

by Mark Brown

An international team of astronomers, led by Australia’s Swinburne University of Technology professor Matthew Bailes, has discovered a planet made of diamond crystals, in our own Milky Way galaxy.

The planet is relatively small at around 60,000 km in diameter (still, it’s five times the size of Earth). But despite its diminutive stature, this crystal space rock has more mass than the solar system’s gas giant Jupiter.

Radio telescope data shows that it orbits its star at a distance of 600,000 km, making years on planet diamond just two hours long. Any closer and it would be ripped to shreds by the star’s gravitational tug. Putting together its immense mass and close orbit, researchers can reveal the planet’s unique makeup.

It’s “likely to be largely carbon and oxygen,” said Michael Keith, one of the research team members, in a press release. Lighter elements, “like hydrogen and helium would be too big to fit the measured orbiting times”. The object’s density means that the material is certain to be crystalline, meaning a large part of the planet may be similar to a diamond.

Read more:

An international team of astronomers, led by Australia’s Swinburne University of Technology professor Matthew Bailes, has discovered a planet made of diamond crystals, in our own Milky Way galaxy.

The planet is relatively small at around 60,000 km in diameter (still, it’s five times the size of Earth). But despite its diminutive stature, this crystal space rock has more mass than the solar system’s gas giant Jupiter.

Radio telescope data shows that it orbits its star at a distance of 600,000 km, making years on planet diamond just two hours long. Any closer and it would be ripped to shreds by the star’s gravitational tug. Putting together its immense mass and close orbit, researchers can reveal the planet’s unique makeup.

It’s “likely to be largely carbon and oxygen,” said Michael Keith, one of the research team members, in a press release. Lighter elements, “like hydrogen and helium would be too big to fit the measured orbiting times”. The object’s density means that the material is certain to be crystalline, meaning a large part of the planet may be similar to a diamond.

Read more:

Thursday, August 25, 2011

Creation Myth

Xerox PARC, Apple, and the truth about innovation

by Malcolm Gladwell

In late 1979, a twenty-four-year-old entrepreneur paid a visit to a research center in Silicon Valley called Xerox PARC. He was the co-founder of a small computer startup down the road, in Cupertino. His name was Steve Jobs.

Xerox PARC was the innovation arm of the Xerox Corporation. It was, and remains, on Coyote Hill Road, in Palo Alto, nestled in the foothills on the edge of town, in a long, low concrete building, with enormous terraces looking out over the jewels of Silicon Valley. To the northwest was Stanford University’s Hoover Tower. To the north was Hewlett-Packard’s sprawling campus. All around were scores of the other chip designers, software firms, venture capitalists, and hardware-makers. A visitor to PARC, taking in that view, could easily imagine that it was the computer world’s castle, lording over the valley below—and, at the time, this wasn’t far from the truth. In 1970, Xerox had assembled the world’s greatest computer engineers and programmers, and for the next ten years they had an unparalleled run of innovation and invention. If you were obsessed with the future in the seventies, you were obsessed with Xerox PARC—which was why the young Steve Jobs had driven to Coyote Hill Road.

Apple was already one of the hottest tech firms in the country. Everyone in the Valley wanted a piece of it. So Jobs proposed a deal: he would allow Xerox to buy a hundred thousand shares of his company for a million dollars—its highly anticipated I.P.O. was just a year away—if PARC would “open its kimono.” A lot of haggling ensued. Jobs was the fox, after all, and PARC was the henhouse. What would he be allowed to see? What wouldn’t he be allowed to see? Some at PARC thought that the whole idea was lunacy, but, in the end, Xerox went ahead with it. One PARC scientist recalls Jobs as “rambunctious”—a fresh-cheeked, caffeinated version of today’s austere digital emperor. He was given a couple of tours, and he ended up standing in front of a Xerox Alto, PARC’s prized personal computer.

An engineer named Larry Tesler conducted the demonstration. He moved the cursor across the screen with the aid of a “mouse.” Directing a conventional computer, in those days, meant typing in a command on the keyboard. Tesler just clicked on one of the icons on the screen. He opened and closed “windows,” deftly moving from one task to another. He wrote on an elegant word-processing program, and exchanged e-mails with other people at PARC, on the world’s first Ethernet network. Jobs had come with one of his software engineers, Bill Atkinson, and Atkinson moved in as close as he could, his nose almost touching the screen. “Jobs was pacing around the room, acting up the whole time,” Tesler recalled. “He was very excited. Then, when he began seeing the things I could do onscreen, he watched for about a minute and started jumping around the room, shouting, ‘Why aren’t you doing anything with this? This is the greatest thing. This is revolutionary!’ ”

Xerox began selling a successor to the Alto in 1981. It was slow and underpowered—and Xerox ultimately withdrew from personal computers altogether. Jobs, meanwhile, raced back to Apple, and demanded that the team working on the company’s next generation of personal computers change course. He wanted menus on the screen. He wanted windows. He wanted a mouse. The result was the Macintosh, perhaps the most famous product in the history of Silicon Valley.

“If Xerox had known what it had and had taken advantage of its real opportunities,” Jobs said, years later, “it could have been as big as I.B.M. plus Microsoft plus Xerox combined—and the largest high-technology company in the world.”

This is the legend of Xerox PARC. Jobs is the Biblical Jacob and Xerox is Esau, squandering his birthright for a pittance. In the past thirty years, the legend has been vindicated by history. Xerox, once the darling of the American high-technology community, slipped from its former dominance. Apple is now ascendant, and the demonstration in that room in Palo Alto has come to symbolize the vision and ruthlessness that separate true innovators from also-rans. As with all legends, however, the truth is a bit more complicated.

After Jobs returned from PARC, he met with a man named Dean Hovey, who was one of the founders of the industrial-design firm that would become known as IDEO. “Jobs went to Xerox PARC on a Wednesday or a Thursday, and I saw him on the Friday afternoon,” Hovey recalled. “I had a series of ideas that I wanted to bounce off him, and I barely got two words out of my mouth when he said, ‘No, no, no, you’ve got to do a mouse.’ I was, like, ‘What’s a mouse?’ I didn’t have a clue. So he explains it, and he says, ‘You know, [the Xerox mouse] is a mouse that cost three hundred dollars to build and it breaks within two weeks. Here’s your design spec: Our mouse needs to be manufacturable for less than fifteen bucks. It needs to not fail for a couple of years, and I want to be able to use it on Formica and my bluejeans.’ From that meeting, I went to Walgreens, which is still there, at the corner of Grant and El Camino in Mountain View, and I wandered around and bought all the underarm deodorants that I could find, because they had that ball in them. I bought a butter dish. That was the beginnings of the mouse.”

Steve Jobs: The Insanely Great Comeback Kid

by Andrew Leonard

I've never seen a living man receive as many obituaries as Steve Jobs has in the last 24 hours, but I guess it's understandable. The first line of his letter to the "Apple Community" spells it out: "I have always said if there ever came a day when I could no longer meet my duties and expectations as Apple''s CEO, I would be the first to let you know. Unfortunately, that day has come." Those words are a sucker punch to the communal solar plexus -- it's impossible to imagine anything other than severe illness that would impel Jobs to step down from running the show -- except maybe a palace coup. And we've already been there, done that. There will be no reruns. Apple is currently the most successful and influential company on the planet -- nobody, anywhere, questions the quality of his leadership.

I've never seen a living man receive as many obituaries as Steve Jobs has in the last 24 hours, but I guess it's understandable. The first line of his letter to the "Apple Community" spells it out: "I have always said if there ever came a day when I could no longer meet my duties and expectations as Apple''s CEO, I would be the first to let you know. Unfortunately, that day has come." Those words are a sucker punch to the communal solar plexus -- it's impossible to imagine anything other than severe illness that would impel Jobs to step down from running the show -- except maybe a palace coup. And we've already been there, done that. There will be no reruns. Apple is currently the most successful and influential company on the planet -- nobody, anywhere, questions the quality of his leadership.

And that's what's so amazing about the Steve Jobs story. It's easy enough to rhapsodize over Jobs' incredible track record -- his accomplishments include the first great personal computer, the transformation of both the music and the telephone business, and the creation of one of the greatest movie-making studios of our time. Just writing that sentence is breathtaking. We will not see its like again. But for me, Jobs' career signifies something more primal -- his comeback saga is a story of redemption, a fantasy epic in which a great king is toppled, but through force of will and grit and brilliance fights his way all the way back to the throne, and inaugurates an even greater empire. It's hard to think of parallels. Mohammed Ali, maybe.

America loves underdogs and comeback kids and winners. Jobs' career arc fills all of those bills. You don't have to be a Windows guy or a Mac guy to appreciate this. All you have to do is love a great story. And the story of how Jobs got pushed out of Apple by a man he personally hand-picked to help run his company, how the company teetered perilously close to bankruptcy, and how Jobs came back to lead Apple to unthinkable success is one hell of an insanely great yarn.

Read more:

image credit:

I've never seen a living man receive as many obituaries as Steve Jobs has in the last 24 hours, but I guess it's understandable. The first line of his letter to the "Apple Community" spells it out: "I have always said if there ever came a day when I could no longer meet my duties and expectations as Apple''s CEO, I would be the first to let you know. Unfortunately, that day has come." Those words are a sucker punch to the communal solar plexus -- it's impossible to imagine anything other than severe illness that would impel Jobs to step down from running the show -- except maybe a palace coup. And we've already been there, done that. There will be no reruns. Apple is currently the most successful and influential company on the planet -- nobody, anywhere, questions the quality of his leadership.

I've never seen a living man receive as many obituaries as Steve Jobs has in the last 24 hours, but I guess it's understandable. The first line of his letter to the "Apple Community" spells it out: "I have always said if there ever came a day when I could no longer meet my duties and expectations as Apple''s CEO, I would be the first to let you know. Unfortunately, that day has come." Those words are a sucker punch to the communal solar plexus -- it's impossible to imagine anything other than severe illness that would impel Jobs to step down from running the show -- except maybe a palace coup. And we've already been there, done that. There will be no reruns. Apple is currently the most successful and influential company on the planet -- nobody, anywhere, questions the quality of his leadership.And that's what's so amazing about the Steve Jobs story. It's easy enough to rhapsodize over Jobs' incredible track record -- his accomplishments include the first great personal computer, the transformation of both the music and the telephone business, and the creation of one of the greatest movie-making studios of our time. Just writing that sentence is breathtaking. We will not see its like again. But for me, Jobs' career signifies something more primal -- his comeback saga is a story of redemption, a fantasy epic in which a great king is toppled, but through force of will and grit and brilliance fights his way all the way back to the throne, and inaugurates an even greater empire. It's hard to think of parallels. Mohammed Ali, maybe.

America loves underdogs and comeback kids and winners. Jobs' career arc fills all of those bills. You don't have to be a Windows guy or a Mac guy to appreciate this. All you have to do is love a great story. And the story of how Jobs got pushed out of Apple by a man he personally hand-picked to help run his company, how the company teetered perilously close to bankruptcy, and how Jobs came back to lead Apple to unthinkable success is one hell of an insanely great yarn.

Read more:

image credit:

Wednesday, August 24, 2011

The World's Best Travel Book

"The Way of the World" is a 1950s travelogue of a trip that Nicolas Bouvier and Thierry Vernet took from Geneva to the Khyber Pass in their faithful FIAT Topolino. Bouvier’s account is now famous amongst travel literature lovers and is generally considered to be the best travel book ever written.

by Henri Lagouleme

There is plenty of competition for the title of best ever travel book: Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts; A.W. Kinglake’s Eothen; Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia or Robert Byron’s The Road to Oxiana have all been cited as the very best of the genre at one time or another. Travel Writing has attracted many a famous name but being a genius of fiction is certainly no guarantee of accomplishment as Henry James’s (A Little Tour in France) or Dostoyevsky’s (Winter Notes on Summer Impressions) incursions into the field make clear. Travel writing is an art of its own and requires specific gifts, imagination is one of them but force and depth of character are probably the key to success – which is where Nicolas Bouvier beats them all hands down.

There is plenty of competition for the title of best ever travel book: Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts; A.W. Kinglake’s Eothen; Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia or Robert Byron’s The Road to Oxiana have all been cited as the very best of the genre at one time or another. Travel Writing has attracted many a famous name but being a genius of fiction is certainly no guarantee of accomplishment as Henry James’s (A Little Tour in France) or Dostoyevsky’s (Winter Notes on Summer Impressions) incursions into the field make clear. Travel writing is an art of its own and requires specific gifts, imagination is one of them but force and depth of character are probably the key to success – which is where Nicolas Bouvier beats them all hands down.

Bouvier outlines the nature of the trip: “We denied ourselves every luxury except one, that of being slow.” He and Vernet did exactly that, setting off at a leisurely pace with very little money –only enough for a few months – thus throwing themselves into the hands of fate. Bouvier and Vernet were no trailblazers, neither were they Jack Kerouacs out for “kicks”. “Taking your time is the best way not to lose it”, Bouvier advises. They were out for a slow and full immersion into the whole business of travelling and discovery: “Travel provides occasions for shaking oneself up but not, as people believe, freedom.” And “Travelling outgrows its motives. It soon proves sufficient in itself. You think you are making a trip, but soon it is making you—or unmaking you.”

The success of the book is mainly due to Bouvier’s literary style. He is disarmingly humane and poetic and comes across as the antithesis to the presumptuous traveller: strangely lovable, completely without guile and very smart.

He treats everyone he meets as an equal, from down-and-out Serbian artisans, to bored border guards, to a Texan consultant pulling his hair out in Tabriz, and restaurant owners with colourful pasts in Quetta, gypsies, Iranian long-distance lorry drivers and the doctors he fortuitously meets along the way who put him back together again. Bouvier’s intelligence is profound and above all generous and thoughtful. Despite throwing his life to the four winds on this slightly madcap escapade, there is something sensible about the man – his critical eye never abandons him.

Bouvier and Thierry Vernet set off from former Yugoslavia in 1953, determined to reach Kabul. They believed, as everyone does, that Kabul was at the ends of the earth, only to discover that – as King Babur (the 15th century founder of the Mogul dynasty in India) reminds us in his memoirs – Kabul is actually the centre of the earth. Bouvier does not disagree – quoting Babur at length.

by Henri Lagouleme

There is plenty of competition for the title of best ever travel book: Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts; A.W. Kinglake’s Eothen; Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia or Robert Byron’s The Road to Oxiana have all been cited as the very best of the genre at one time or another. Travel Writing has attracted many a famous name but being a genius of fiction is certainly no guarantee of accomplishment as Henry James’s (A Little Tour in France) or Dostoyevsky’s (Winter Notes on Summer Impressions) incursions into the field make clear. Travel writing is an art of its own and requires specific gifts, imagination is one of them but force and depth of character are probably the key to success – which is where Nicolas Bouvier beats them all hands down.

There is plenty of competition for the title of best ever travel book: Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts; A.W. Kinglake’s Eothen; Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia or Robert Byron’s The Road to Oxiana have all been cited as the very best of the genre at one time or another. Travel Writing has attracted many a famous name but being a genius of fiction is certainly no guarantee of accomplishment as Henry James’s (A Little Tour in France) or Dostoyevsky’s (Winter Notes on Summer Impressions) incursions into the field make clear. Travel writing is an art of its own and requires specific gifts, imagination is one of them but force and depth of character are probably the key to success – which is where Nicolas Bouvier beats them all hands down. Bouvier outlines the nature of the trip: “We denied ourselves every luxury except one, that of being slow.” He and Vernet did exactly that, setting off at a leisurely pace with very little money –only enough for a few months – thus throwing themselves into the hands of fate. Bouvier and Vernet were no trailblazers, neither were they Jack Kerouacs out for “kicks”. “Taking your time is the best way not to lose it”, Bouvier advises. They were out for a slow and full immersion into the whole business of travelling and discovery: “Travel provides occasions for shaking oneself up but not, as people believe, freedom.” And “Travelling outgrows its motives. It soon proves sufficient in itself. You think you are making a trip, but soon it is making you—or unmaking you.”

The success of the book is mainly due to Bouvier’s literary style. He is disarmingly humane and poetic and comes across as the antithesis to the presumptuous traveller: strangely lovable, completely without guile and very smart.

He treats everyone he meets as an equal, from down-and-out Serbian artisans, to bored border guards, to a Texan consultant pulling his hair out in Tabriz, and restaurant owners with colourful pasts in Quetta, gypsies, Iranian long-distance lorry drivers and the doctors he fortuitously meets along the way who put him back together again. Bouvier’s intelligence is profound and above all generous and thoughtful. Despite throwing his life to the four winds on this slightly madcap escapade, there is something sensible about the man – his critical eye never abandons him.

Bouvier and Thierry Vernet set off from former Yugoslavia in 1953, determined to reach Kabul. They believed, as everyone does, that Kabul was at the ends of the earth, only to discover that – as King Babur (the 15th century founder of the Mogul dynasty in India) reminds us in his memoirs – Kabul is actually the centre of the earth. Bouvier does not disagree – quoting Babur at length.

Passion Pit

[ed. It's interesting sometimes to glance at the comments sections of these videos. I guess hipsters are down these days (if it's even possible to come up with a definitive explanation of what a hipster is... music, wise). I guess I post for hipsters, fossils, soul surfers, jazzers, rockers, funkmeisters, grassers, clubbers, blues dudes and anyone else that just finds all kinds of music interesting.]

Adventures in Indiana State Fair Food 2011

by Aaron Carroll

That’s a doughnut burger. They take a Krispy Kreme and put it on the griddle. Then they take a bacon cheeseburger and put it on top. No veggies for us. Of course, it’s topped with another Krispy Kreme. Noah, who has the most discriminating palate in the family, loved this. Aimee will deny liking this, but she darn well tried it. What makes the Indiana State Fair better than any other food adventure you can think of, though, is that the doughnut burger was pretty much the healthiest thing offered at the grill.

Read more:

That’s a doughnut burger. They take a Krispy Kreme and put it on the griddle. Then they take a bacon cheeseburger and put it on top. No veggies for us. Of course, it’s topped with another Krispy Kreme. Noah, who has the most discriminating palate in the family, loved this. Aimee will deny liking this, but she darn well tried it. What makes the Indiana State Fair better than any other food adventure you can think of, though, is that the doughnut burger was pretty much the healthiest thing offered at the grill.

Read more:

This Wine Goes Well With Fish

Brilliant ideas sometimes arise out of pure necessity. Consider Piero Lugano, 63, the suntanned artist-turned-wine-merchant who opened a shop called Bisson in this town on the Italian Riviera in 1978.

Not content merely to sell wine, he soon began making it. Ten years ago he decided to try producing sparkling wine from indigenous varieties grown in vineyards overlooking the Golfo Paradiso on the Mediterranean.

But he immediately encountered a problem: there was simply no space in his already cramped shop and winery to carry out the aging required to make a bottle-fermented sparkling wine in the classic method of Champagne. Then, as he recalled recently, “a light bulb went on in my head: I thought, why not put the wine under the sea?”

This might seem logical to someone like Mr. Lugano who has long struggled to reconcile his twin passions for vine and sea. To most everyone else, the idea of making wine underwater might seem a bit unusual.

But Mr. Lugano makes an interesting argument: “It’s better than even the best underground cellar, especially for sparkling wine. The temperature is perfect, there’s no light, the water prevents even the slightest bit of air from getting in, and the constant counterpressure keeps the bubbles bubbly. Moreover, the underwater currents act like a crib, gently rocking the bottles and keeping the lees moving through the wine.” (The lees refer to yeast particles.)

It’s quite a creative solution to a space problem. But Italy is infamous for its labyrinthine bureaucracy. And the place he wanted to put the wine happened to be in the tightly controlled waters of a national marine preserve, the Area Marina Protetta di Portofino. So the odds would seem overwhelmingly against such a project.

Read more:

Not content merely to sell wine, he soon began making it. Ten years ago he decided to try producing sparkling wine from indigenous varieties grown in vineyards overlooking the Golfo Paradiso on the Mediterranean.

But he immediately encountered a problem: there was simply no space in his already cramped shop and winery to carry out the aging required to make a bottle-fermented sparkling wine in the classic method of Champagne. Then, as he recalled recently, “a light bulb went on in my head: I thought, why not put the wine under the sea?”

This might seem logical to someone like Mr. Lugano who has long struggled to reconcile his twin passions for vine and sea. To most everyone else, the idea of making wine underwater might seem a bit unusual.

But Mr. Lugano makes an interesting argument: “It’s better than even the best underground cellar, especially for sparkling wine. The temperature is perfect, there’s no light, the water prevents even the slightest bit of air from getting in, and the constant counterpressure keeps the bubbles bubbly. Moreover, the underwater currents act like a crib, gently rocking the bottles and keeping the lees moving through the wine.” (The lees refer to yeast particles.)

It’s quite a creative solution to a space problem. But Italy is infamous for its labyrinthine bureaucracy. And the place he wanted to put the wine happened to be in the tightly controlled waters of a national marine preserve, the Area Marina Protetta di Portofino. So the odds would seem overwhelmingly against such a project.

Read more:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)