Monday, April 7, 2014

Why It Is Not Possible to Regulate Robots

If you're a regular reader, you'll know that I believe two things about computers: first, that they are the most significant functional element of most modern artifacts, from cars to houses to hearing aids; and second, that we have dramatically failed to come to grips with this fact. We keep talking about whether 3D printers should be "allowed" to print guns, or whether computers should be "allowed" to make infringing copies, or whether your iPhone should be "allowed" to run software that Apple hasn't approved and put in its App Store.

Practically speaking, though, these all amount to the same question: how do we keep computers from executing certain instructions, even if the people who own those computers want to execute them? And the practical answer is, we can't.

Practically speaking, though, these all amount to the same question: how do we keep computers from executing certain instructions, even if the people who own those computers want to execute them? And the practical answer is, we can't.

Oh, you can make a device that goes a long way to preventing its owner from doing something bad. I have a blender with a great interlock that has thus far prevented me from absentmindedly slicing off my fingers or spraying the kitchen with a one-molecule-thick layer of milkshake. This interlock is the kind of thing that I'm very unlikely to accidentally disable, but if I decided to deliberately sabotage my blender so that it could run with the lid off, it would take me about ten minutes' work and the kind of tools we have in the kitchen junk-drawer.

This blender is a robot. It has an internal heating element that lets you use it as a slow-cooker, and there's a programmable timer for it. It's a computer in a fancy case that includes a whirling, razor-sharp blade. It's not much of a stretch to imagine the computer that controls it receiving instructions by network. Once you design a device to be controlled by a computer, you get the networked part virtually for free, in that the cheapest and most flexible commodity computers we have are designed to interface with networks and the cheapest, most powerful operating systems we have come with networking built in. For the most part, computer-controlled devices are born networked, and disabling their network capability requires a deliberate act.

My kitchen robot has the potential to do lots of harm, from hacking off my fingers to starting fires to running up massive power-bills while I'm away to creating a godawful mess. I am confident that we can do a lot to prevent this stuff: to prevent my robot from harming me through my own sloppiness, to prevent my robot from making mistakes that end up hurting me, and to prevent other people from taking over my robot and using it to hurt me.

The distinction here is between a robot that is designed to do what its owner wants – including asking "are you sure?" when its owner asks it to do something potentially stupid – and a robot that is designed to thwart its owner's wishes. The former is hard, important work and the latter is a fool's errand and dangerous to boot. (....)

Is there such a thing as a robot? An excellent paper by Ryan Calo proposes that there is such a thing as a robot, and that, moreover, many of the thorniest, most interesting legal problems on our horizon will involve them.

As interesting as the paper was, I am unconvinced. A robot is basically a computer that causes some physical change in the world. We can and do regulate machines, from cars to drills to implanted defibrillators. But the thing that distinguishes a power-drill from a robot-drill is that the robot-drill has a driver: a computer that operates it. Regulating that computer in the way that we regulate other machines – by mandating the characteristics of their manufacture – will be no more effective at preventing undesirable robotic outcomes than the copyright mandates of the past 20 years have been effective at preventing copyright infringement (that is, not at all).

But that isn't to say that robots are unregulatable – merely that the locus of the regulation needs to be somewhere other than in controlling the instructions you are allowed to give a computer. For example, we might mandate that manufacturers subject code to a certain suite of rigorous public reviews, or that the code be able to respond correctly in a set of circumstances (in the case of a self-driving car, this would basically be a driving test for robots). Insurers might require certain practices in product design as a condition of cover. Courts might find liability for certain programming practices and not for others. Consumer groups like Which? and Consumer Union might publish advice about things that purchasers should look for when buying devices. Professional certification bodies, such as national colleges of engineering, might enshrine principles of ethical software practice into their codes of conduct, and strike off members found to be unethical according to these principles.

by Cory Doctorow, The Guardian | Read more:

Image: Blutgruppe/ Blutgruppe/Corbis

Practically speaking, though, these all amount to the same question: how do we keep computers from executing certain instructions, even if the people who own those computers want to execute them? And the practical answer is, we can't.

Practically speaking, though, these all amount to the same question: how do we keep computers from executing certain instructions, even if the people who own those computers want to execute them? And the practical answer is, we can't.Oh, you can make a device that goes a long way to preventing its owner from doing something bad. I have a blender with a great interlock that has thus far prevented me from absentmindedly slicing off my fingers or spraying the kitchen with a one-molecule-thick layer of milkshake. This interlock is the kind of thing that I'm very unlikely to accidentally disable, but if I decided to deliberately sabotage my blender so that it could run with the lid off, it would take me about ten minutes' work and the kind of tools we have in the kitchen junk-drawer.

This blender is a robot. It has an internal heating element that lets you use it as a slow-cooker, and there's a programmable timer for it. It's a computer in a fancy case that includes a whirling, razor-sharp blade. It's not much of a stretch to imagine the computer that controls it receiving instructions by network. Once you design a device to be controlled by a computer, you get the networked part virtually for free, in that the cheapest and most flexible commodity computers we have are designed to interface with networks and the cheapest, most powerful operating systems we have come with networking built in. For the most part, computer-controlled devices are born networked, and disabling their network capability requires a deliberate act.

My kitchen robot has the potential to do lots of harm, from hacking off my fingers to starting fires to running up massive power-bills while I'm away to creating a godawful mess. I am confident that we can do a lot to prevent this stuff: to prevent my robot from harming me through my own sloppiness, to prevent my robot from making mistakes that end up hurting me, and to prevent other people from taking over my robot and using it to hurt me.

The distinction here is between a robot that is designed to do what its owner wants – including asking "are you sure?" when its owner asks it to do something potentially stupid – and a robot that is designed to thwart its owner's wishes. The former is hard, important work and the latter is a fool's errand and dangerous to boot. (....)

Is there such a thing as a robot? An excellent paper by Ryan Calo proposes that there is such a thing as a robot, and that, moreover, many of the thorniest, most interesting legal problems on our horizon will involve them.

As interesting as the paper was, I am unconvinced. A robot is basically a computer that causes some physical change in the world. We can and do regulate machines, from cars to drills to implanted defibrillators. But the thing that distinguishes a power-drill from a robot-drill is that the robot-drill has a driver: a computer that operates it. Regulating that computer in the way that we regulate other machines – by mandating the characteristics of their manufacture – will be no more effective at preventing undesirable robotic outcomes than the copyright mandates of the past 20 years have been effective at preventing copyright infringement (that is, not at all).

But that isn't to say that robots are unregulatable – merely that the locus of the regulation needs to be somewhere other than in controlling the instructions you are allowed to give a computer. For example, we might mandate that manufacturers subject code to a certain suite of rigorous public reviews, or that the code be able to respond correctly in a set of circumstances (in the case of a self-driving car, this would basically be a driving test for robots). Insurers might require certain practices in product design as a condition of cover. Courts might find liability for certain programming practices and not for others. Consumer groups like Which? and Consumer Union might publish advice about things that purchasers should look for when buying devices. Professional certification bodies, such as national colleges of engineering, might enshrine principles of ethical software practice into their codes of conduct, and strike off members found to be unethical according to these principles.

by Cory Doctorow, The Guardian | Read more:

Image: Blutgruppe/ Blutgruppe/Corbis

Portraits of Reconciliation

NZABAMWITA: “I damaged and looted her property. I spent nine and a half years in jail. I had been educated to know good from evil before being released. And when I came home, I thought it would be good to approach the person to whom I did evil deeds and ask for her forgiveness. I told her that I would stand by her, with all the means at my disposal. My own father was involved in killing her children. When I learned that my parent had behaved wickedly, for that I profoundly begged her pardon, too.”

KAMPUNDU: “My husband was hiding, and men hunted him down and killed him on a Tuesday. The following Tuesday, they came back and killed my two sons. I was hoping that my daughters would be saved, but then they took them to my husband’s village and killed them and threw them in the latrine. I was not able to remove them from that hole. I knelt down and prayed for them, along with my younger brother, and covered the latrine with dirt. The reason I granted pardon is because I realized that I would never get back the beloved ones I had lost. I could not live a lonely life — I wondered, if I was ill, who was going to stay by my bedside, and if I was in trouble and cried for help, who was going to rescue me? I preferred to grant pardon.”

Last month, the photographer Pieter Hugo went to southern Rwanda, two decades after nearly a million people were killed during the country’s genocide, and captured a series of unlikely, almost unthinkable tableaus. In one, a woman rests her hand on the shoulder of the man who killed her father and brothers. In another, a woman poses with a casually reclining man who looted her property and whose father helped murder her husband and children. In many of these photos, there is little evident warmth between the pairs, and yet there they are, together. In each, the perpetrator is a Hutu who was granted pardon by the Tutsi survivor of his crime. (...)

At the photo shoots, Hugo said, the relationships between the victims and the perpetrators varied widely. Some pairs showed up and sat easily together, chatting about village gossip. Others arrived willing to be photographed but unable to go much further. “There’s clearly different degrees of forgiveness,” Hugo said. “In the photographs, the distance or closeness you see is pretty accurate.”

In interviews conducted by AMI and Creative Court for the project, the subjects spoke of the pardoning process as an important step toward improving their lives. “These people can’t go anywhere else — they have to make peace,” Hugo explained. “Forgiveness is not born out of some airy-fairy sense of benevolence. It’s more out of a survival instinct.” Yet the practical necessity of reconciliation does not detract from the emotional strength required of these Rwandans to forge it — or to be photographed, for that matter, side by side.

At the photo shoots, Hugo said, the relationships between the victims and the perpetrators varied widely. Some pairs showed up and sat easily together, chatting about village gossip. Others arrived willing to be photographed but unable to go much further. “There’s clearly different degrees of forgiveness,” Hugo said. “In the photographs, the distance or closeness you see is pretty accurate.”

In interviews conducted by AMI and Creative Court for the project, the subjects spoke of the pardoning process as an important step toward improving their lives. “These people can’t go anywhere else — they have to make peace,” Hugo explained. “Forgiveness is not born out of some airy-fairy sense of benevolence. It’s more out of a survival instinct.” Yet the practical necessity of reconciliation does not detract from the emotional strength required of these Rwandans to forge it — or to be photographed, for that matter, side by side.

by Susan Dominus, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Pieter Hugo

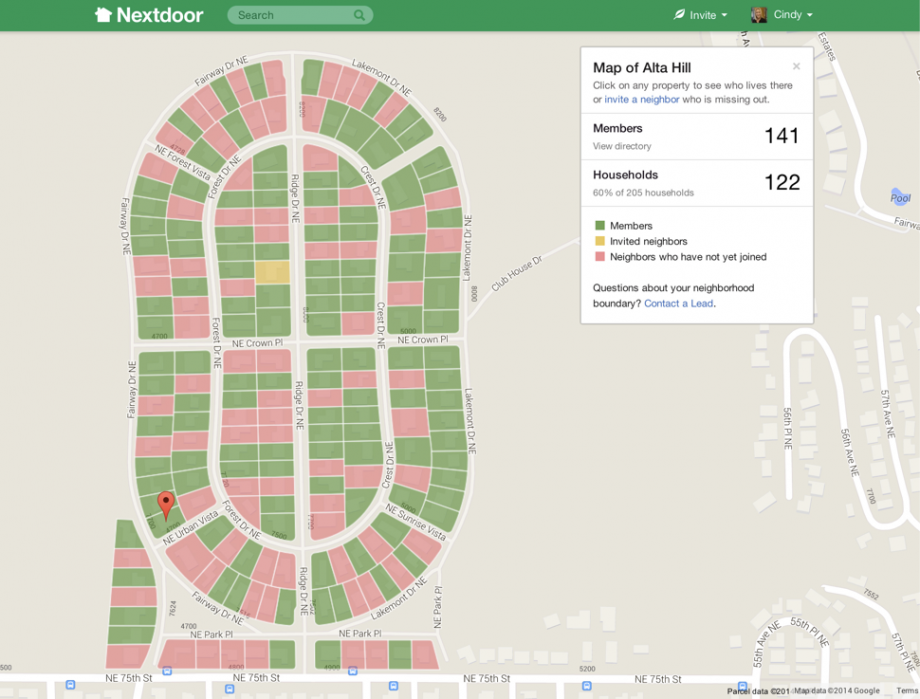

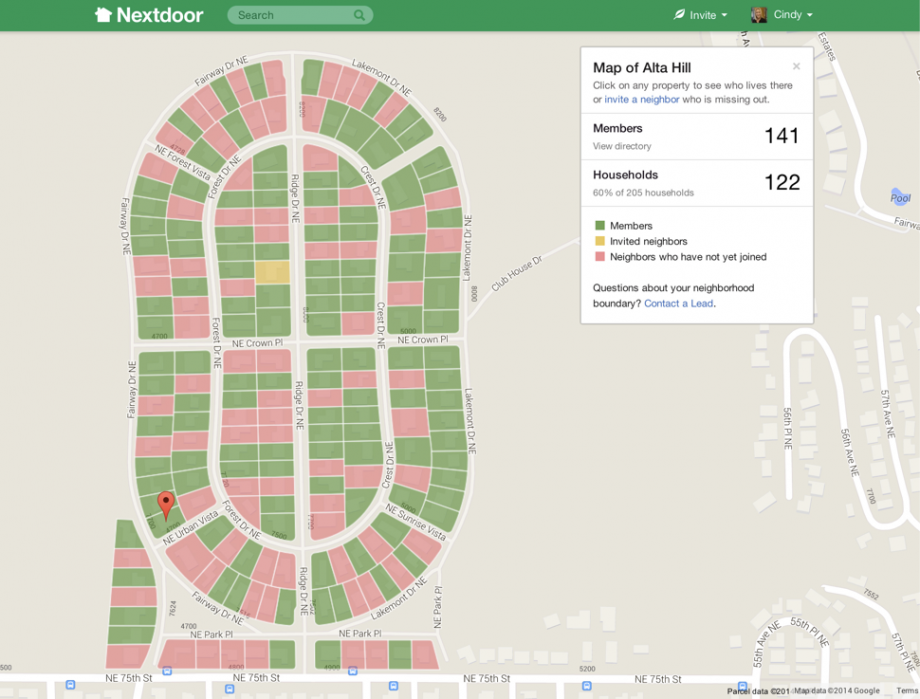

Building the Facebook of Neighborhoods

[ed. I've thought for a long time that something like this would be useful, if for no other reason than to share information about crime in our neighborhoods (and, wondered why the police didn't take the initiative to create neighborhood web sites themselves). This is more elaborate].

Having her bike yanked from the utility closet of her San Francisco apartment building reminded Sarah Leary why she had spent the last three years building an online social network for neighbors.

"I put out a message saying, ‘Here’s what my bike looks like,’” says Leary, co-creator of Nextdoor, “and I had three or four people chime in with just, like, ‘I’m so sorry that that happened.’” (She added that those few posted words alone “made her feel known and loved and supported.”) Other neighbors were more practical. One insisted that she file a report so that the police might add it to the stats used to track local bicycle thievery.

"I put out a message saying, ‘Here’s what my bike looks like,’” says Leary, co-creator of Nextdoor, “and I had three or four people chime in with just, like, ‘I’m so sorry that that happened.’” (She added that those few posted words alone “made her feel known and loved and supported.”) Other neighbors were more practical. One insisted that she file a report so that the police might add it to the stats used to track local bicycle thievery.

Oh right, Leary, a Massachusetts native and tech world veteran who now lives in the Lower Pacific Heights neighborhood, recalls thinking. I’m supposed to do something about this for my neighborhood in real life, not just gripe about it online.

The site co-founded by Leary is a simple enough idea. We’ve become acclimated to using Facebook to connect with friends and family. LinkedIn for work. Twitter for our interests. Yet in 2014 there is no go-to online social network for the people we live among. "And that," Leary says while sitting in Nextdoor’s suite of offices, "is kind of crazy."

The Nextdoor team, Leary says, draws some of its inspiration from Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam, who concluded in his 2000 book Bowling Alone that "social networks in a neighborhood" make crime go down and test scores go up. Even more fundamentally, our neighbors would be the first to dig us out from the rubble after an earthquake. But today, we don’t know them that well. Nearly a third of Americans can’t pick out a single person in their neighborhood by name. For all the talk about technology driving us ever further into our personal bubbles — Putnam used “social networks” in the pre-Facebook sense — Nextdoor’s gamble is that the Internet can, in fact, be the missing bridge between us and the people with whom we share a spot on the map. (...)

The ultimate goal is to make information shared on Nextdoor so valuable that people don’t want to miss it — a bet on the notion that far more people care about, say, what happens at community meetings than attendance numbers suggest. It’s a vision of Nextdoor less as a social network than as a social utility.

Having her bike yanked from the utility closet of her San Francisco apartment building reminded Sarah Leary why she had spent the last three years building an online social network for neighbors.

"I put out a message saying, ‘Here’s what my bike looks like,’” says Leary, co-creator of Nextdoor, “and I had three or four people chime in with just, like, ‘I’m so sorry that that happened.’” (She added that those few posted words alone “made her feel known and loved and supported.”) Other neighbors were more practical. One insisted that she file a report so that the police might add it to the stats used to track local bicycle thievery.

"I put out a message saying, ‘Here’s what my bike looks like,’” says Leary, co-creator of Nextdoor, “and I had three or four people chime in with just, like, ‘I’m so sorry that that happened.’” (She added that those few posted words alone “made her feel known and loved and supported.”) Other neighbors were more practical. One insisted that she file a report so that the police might add it to the stats used to track local bicycle thievery.Oh right, Leary, a Massachusetts native and tech world veteran who now lives in the Lower Pacific Heights neighborhood, recalls thinking. I’m supposed to do something about this for my neighborhood in real life, not just gripe about it online.

The site co-founded by Leary is a simple enough idea. We’ve become acclimated to using Facebook to connect with friends and family. LinkedIn for work. Twitter for our interests. Yet in 2014 there is no go-to online social network for the people we live among. "And that," Leary says while sitting in Nextdoor’s suite of offices, "is kind of crazy."

The Nextdoor team, Leary says, draws some of its inspiration from Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam, who concluded in his 2000 book Bowling Alone that "social networks in a neighborhood" make crime go down and test scores go up. Even more fundamentally, our neighbors would be the first to dig us out from the rubble after an earthquake. But today, we don’t know them that well. Nearly a third of Americans can’t pick out a single person in their neighborhood by name. For all the talk about technology driving us ever further into our personal bubbles — Putnam used “social networks” in the pre-Facebook sense — Nextdoor’s gamble is that the Internet can, in fact, be the missing bridge between us and the people with whom we share a spot on the map. (...)

The ultimate goal is to make information shared on Nextdoor so valuable that people don’t want to miss it — a bet on the notion that far more people care about, say, what happens at community meetings than attendance numbers suggest. It’s a vision of Nextdoor less as a social network than as a social utility.

by Nancy Scola, Next City | Read more:

Image: Nextdoor

Sunday, April 6, 2014

The New Normal

[ed. Remember folks, you heard it here first.]

2. A sociocultural concept, c. 2013, having nothing to do with fashion, that concerns hipster types learning to get over themselves, sometimes even enough to enjoy mainstream pleasures like football along with the rest of the crowd.

3. An Internet meme that turned into a massive in-joke that the news media keeps falling for. (See below).

A little more than a month ago, the word “normcore” spread like a brush fire across the fashionable corners of the Internet, giving name to a supposed style trend where dressing like a tourist — non-ironic sweatshirts, white sneakers and Jerry Seinfeld-like dad jeans — is the ultimate fashion statement.

As widely interpreted, normcore was mall chic for people — mostly the downtown/Brooklyn creative crowd — who would not be caught dead in a shopping mall. Forget Martin Van Buren mutton chops; the way to stand out on the streets of Bushwick in 2014, apparently, is in a pair of Gap cargo shorts, a Coors Light T-shirt and a Nike golf hat. (...)

A style revolution? A giant in-joke? At this point, it hardly seems to matter. After a month-plus blizzard of commentary, normcore may be a hypothetical movement that turns into a real movement through the power of sheer momentum.

Even so, the fundamental question — is normcore real? — remains a matter of debate, even among the people who foisted the term upon the world. (...)

Like a mass sociological experiment, the question now is whether repetition, at a certain point, makes reality. Even those who coined the phrase concede that normcore has taken on a life of its own. “If you look through #normcore on Twitter or Instagram, people are definitely posting pictures of that look,” said Gregory Fong, a K-Hole founder. “Whether they believe it’s real or a joke, it’s impossible to say, but it’s there and it’s happening.”

It certainly seems to be. Sort of.

by Alex Williams, NY Times | Read more:

Image: uncredited

“It is an interesting subject: superfluous people in the service of brute power. A developed, stable, organized society is a community of clearly delineated and defined roles, something that cannot be said of the majority of third-world cities. Their neighborhoods are populated in large part by an unformed, fluid element, lacking precise classification, without position, place, or purpose. At any moment and for whatever reason, these people, to whom no one pays attention, whom no one needs, can form into a crowd, a throng, a mob, which has an opinion about everything, has time for everything, and would like to participate in something, mean something.

“All dictatorships take advantage of this idle magma. They don’t even need to maintain an expensive army of full-time policemen. It suffices to reach out to these people searching for some significance in life. Give them the sense that they can be of use, that someone is counting on them for something, that they have been noticed, that they have a purpose.”

Ryszard Kapuściński, from “Problem, No Problem.”

Photography: Judy Dater

via:

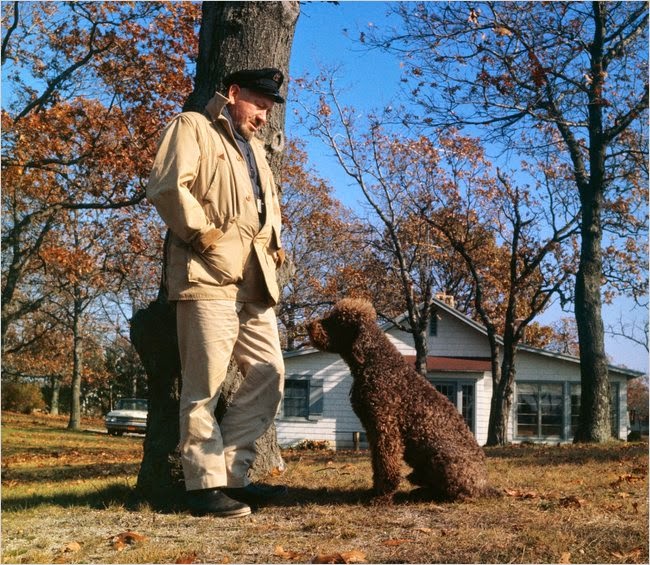

A Small Gain in Yardage

Who doesn't like to be a center for concern? A kind of second childhood falls on so many men. They trade their violence for the promise of a small increase of life span. In effect, the head of the house becomes the youngest child. And I have searched myself for this possibility with a kind of horror. For I have always lived violently, drunk hugely, eaten too much or not at all, slept around the clock or missed two nights of sleeping, worked too hard and too long in glory, or slobbed for a time in utter laziness. I've lifted, pulled, chopped, climbed, made love with joy and taken my hangovers as a consequence, not as a punishment. I did not want to surrender fierceness for a small gain in yardage... And in my own life, I am not willing to trade quality for quantity.

~ John Steinbeck, Travels With Charley

image: Bettmann/Corbis via:

The Perfect Lobby: How One Industry Captured Washington, DC

Many of America’s for-profit colleges have proven themselves a bad deal for the students lured by their enticing promises—as well as for US taxpayers, who subsidize these institutions with ten of billions annually in federal student aid.

More than half of the students who enroll in for-profit colleges—many of them veterans, single mothers, and other low- and middle-income people aiming for jobs like medical technician, diesel mechanic or software coder—drop out within about four months. Many of these colleges have been caught using deceptive advertising and misleading prospective students about program costs and job placement rates. Although the for-profits promise that their programs are affordable, the real cost can be nearly double that of Harvard or Stanford. But the quality of the programs are often weak, so even students who manage to graduate often struggle to find jobs beyond the Office Depot shifts they previously held. The US Department of Education recently reported that 72 percent of the for-profit college programs it analyzed produced graduates who, on average, earned less than high school dropouts.

More than half of the students who enroll in for-profit colleges—many of them veterans, single mothers, and other low- and middle-income people aiming for jobs like medical technician, diesel mechanic or software coder—drop out within about four months. Many of these colleges have been caught using deceptive advertising and misleading prospective students about program costs and job placement rates. Although the for-profits promise that their programs are affordable, the real cost can be nearly double that of Harvard or Stanford. But the quality of the programs are often weak, so even students who manage to graduate often struggle to find jobs beyond the Office Depot shifts they previously held. The US Department of Education recently reported that 72 percent of the for-profit college programs it analyzed produced graduates who, on average, earned less than high school dropouts.

Today, 13 percent of all college students attend for-profit colleges, on campuses and online—but these institutions account for 47 percent of student loan defaults. For-profit schools are driving a national student debt crisis that has reached $1.2 trillion in borrowing. They absorb a quarter of all federal student aid—more than $30 billion annually—diverting sums from better, more affordable programs at nonprofit and public colleges. Many for-profit college companies, including most of the biggest ones, get almost 90 percent of their revenue from taxpayers.

So why does Washington keep the money flowing?

It’s not that politicians are unaware of the problem. One person who clearly understands the human and financial costs of the for-profit college industry is President Obama. Speaking at Fort Stewart, Georgia, in April 2012, the president told the soldiers that some schools are "trying to swindle and hoodwink" them, because they only “care about the cash." Speaking off the cuff last year, Obama warned that some for-profit colleges were failing to provide the certification that students thought they would get. In the end, he said, the students "can't find a job. They default.... Their credit is ruined, and the for-profit institution is making out like a bandit." And, he noted, when students default on their federally backed loans, “the taxpayer ends up holding the bag.”

On March 14, the administration released its much-anticipated draft "gainful employment" rule, aimed at ending taxpayer support for career college programs that consistently leave students with insurmountable debt.

This rule would have a real impact: it would eventually cut off federal student grants and loans to the very worst career education programs, whose students consistently earn far too little to pay down their college loans, or whose students have very high rates of loan defaults.

But advocates believe that the standards in the proposed rule are too weak; they would leave standing many programs that harm a high percentage of their students. The rule , they argue, doesn’t do enough to ensure that federal aid goes only to programs that actually help students prepare for careers. But it isn’t soft enough to satisfy APSCU, the trade association representing for-profit colleges, which denounced the rule as the flawed product of a “sham” process. The administration gave the public until May 27 to comment before issuing a final rule.

APSCU and other lobbyists for the for-profit college industry are now out in full force, hoping to extract from the gainful employment rule its remaining teeth. Supporters of stronger standards to protect students from industry predation—among them the NAACP, the Consumers Union, Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, the Service Employees International Union and others (including, full disclosure, myself)—will push back, but they have far fewer financial resources for the battle. This is a crucial round in a long fight, one in which the industry has already displayed a willingness to spend tens of millions to manipulate the machinery of modern influence-peddling—and with a remarkable degree of success.

Because most of this lobbying money is financed by taxpayers, this is a story of how Washington itself created a monster—one so big that it can work its will on the political system even when the facts cry out for reform and accountability.

More than half of the students who enroll in for-profit colleges—many of them veterans, single mothers, and other low- and middle-income people aiming for jobs like medical technician, diesel mechanic or software coder—drop out within about four months. Many of these colleges have been caught using deceptive advertising and misleading prospective students about program costs and job placement rates. Although the for-profits promise that their programs are affordable, the real cost can be nearly double that of Harvard or Stanford. But the quality of the programs are often weak, so even students who manage to graduate often struggle to find jobs beyond the Office Depot shifts they previously held. The US Department of Education recently reported that 72 percent of the for-profit college programs it analyzed produced graduates who, on average, earned less than high school dropouts.

More than half of the students who enroll in for-profit colleges—many of them veterans, single mothers, and other low- and middle-income people aiming for jobs like medical technician, diesel mechanic or software coder—drop out within about four months. Many of these colleges have been caught using deceptive advertising and misleading prospective students about program costs and job placement rates. Although the for-profits promise that their programs are affordable, the real cost can be nearly double that of Harvard or Stanford. But the quality of the programs are often weak, so even students who manage to graduate often struggle to find jobs beyond the Office Depot shifts they previously held. The US Department of Education recently reported that 72 percent of the for-profit college programs it analyzed produced graduates who, on average, earned less than high school dropouts.Today, 13 percent of all college students attend for-profit colleges, on campuses and online—but these institutions account for 47 percent of student loan defaults. For-profit schools are driving a national student debt crisis that has reached $1.2 trillion in borrowing. They absorb a quarter of all federal student aid—more than $30 billion annually—diverting sums from better, more affordable programs at nonprofit and public colleges. Many for-profit college companies, including most of the biggest ones, get almost 90 percent of their revenue from taxpayers.

So why does Washington keep the money flowing?

It’s not that politicians are unaware of the problem. One person who clearly understands the human and financial costs of the for-profit college industry is President Obama. Speaking at Fort Stewart, Georgia, in April 2012, the president told the soldiers that some schools are "trying to swindle and hoodwink" them, because they only “care about the cash." Speaking off the cuff last year, Obama warned that some for-profit colleges were failing to provide the certification that students thought they would get. In the end, he said, the students "can't find a job. They default.... Their credit is ruined, and the for-profit institution is making out like a bandit." And, he noted, when students default on their federally backed loans, “the taxpayer ends up holding the bag.”

On March 14, the administration released its much-anticipated draft "gainful employment" rule, aimed at ending taxpayer support for career college programs that consistently leave students with insurmountable debt.

This rule would have a real impact: it would eventually cut off federal student grants and loans to the very worst career education programs, whose students consistently earn far too little to pay down their college loans, or whose students have very high rates of loan defaults.

But advocates believe that the standards in the proposed rule are too weak; they would leave standing many programs that harm a high percentage of their students. The rule , they argue, doesn’t do enough to ensure that federal aid goes only to programs that actually help students prepare for careers. But it isn’t soft enough to satisfy APSCU, the trade association representing for-profit colleges, which denounced the rule as the flawed product of a “sham” process. The administration gave the public until May 27 to comment before issuing a final rule.

APSCU and other lobbyists for the for-profit college industry are now out in full force, hoping to extract from the gainful employment rule its remaining teeth. Supporters of stronger standards to protect students from industry predation—among them the NAACP, the Consumers Union, Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, the Service Employees International Union and others (including, full disclosure, myself)—will push back, but they have far fewer financial resources for the battle. This is a crucial round in a long fight, one in which the industry has already displayed a willingness to spend tens of millions to manipulate the machinery of modern influence-peddling—and with a remarkable degree of success.

Because most of this lobbying money is financed by taxpayers, this is a story of how Washington itself created a monster—one so big that it can work its will on the political system even when the facts cry out for reform and accountability.

by David Halperin, The Nation | Read more:

Image: Brian Ach / AP Images for DeVry UniversityDebunking Alcoholics Anonymous: Behind the Myths of Recovery

Myths have a way of coming to resemble facts through repetition alone. This is as true in science and psychology as in politics and history. Today few areas of public health are more riven with unsubstantiated claims than the field of addiction.

Alcoholics Anonymous has been instrumental in the widespread adoption of many such myths. The organization’s Twelve Steps, its expressions, and unique lexicon have found their way into the public discourse in a way that few other “brands” could ever match. So ingrained are these ideas, in fact, that many Americans would be hard-pressed to identify which came from AA and which from scientific investigation.

Alcoholics Anonymous has been instrumental in the widespread adoption of many such myths. The organization’s Twelve Steps, its expressions, and unique lexicon have found their way into the public discourse in a way that few other “brands” could ever match. So ingrained are these ideas, in fact, that many Americans would be hard-pressed to identify which came from AA and which from scientific investigation.

The unfortunate part of this cultural penetration is that many addiction myths are harmful or even destructive, perpetuating false ideas about who addicts are, what addiction is, and what is needed to quit for good. In this chapter, I’d like to take a look at a few of these myths and examine some of the ways they impair efforts at adopting a more effective approach.

MYTH #1: YOU HAVE TO “HIT BOTTOM” BEFORE YOU CAN GET WELL

This common myth essentially says that an addict needs to reach a point of absolute loss or despair before he or she can begin to climb back toward a safe and productive life.

The most common objection to this myth is simple logic: nobody can possibly know where their “bottom” is until they identify it in retrospect. One person’s lowest point could be a night on the street, while another’s could be a bad day at work or even a small personal humiliation. It’s not unusual for one “bottom” to make way for another following a relapse. Without a clear definition, this is a concept that could be useful only in hindsight, if it is useful at all.

A bigger problem with this notion is the idea that addiction is in some fundamental way just a matter of stubbornness or stupidity—that is, addicts cannot recover until they are shown the consequences of their actions in a forceful enough way. This is a dressed-up version of the idea that addiction is a conscious choice and that stopping is a matter of recognizing the damage it causes. I have said it before, but it bears repeating: if consequences alone were enough to make someone stop repeating an addictive behavior, there would be no addicts. One of the defining agonies of addiction is that people can’t stop despite being well aware of the devastating consequences. That millions of people who have lost their jobs, marriages, and families are still unable to quit should be a clear indication that loss and despair, even in overwhelming quantities, aren’t enough to cure addiction. Conversely, many addicts stop their behavior at a point where they have not hit bottom in any sense.

There is a moralistic subtext at work here as well. The notion that addicts have to hit bottom suggests that they are too selfish to quit until they have paid a steep enough personal price. Once again we get an echo of the medieval notion of penance here: through suffering comes purity. Addicts no more need to experience devastating personal loss than does anyone else with a problem. Yes, it can be useful when a single moment helps to crystallize that one has a problem, but the fantasy that this moment must be especially painful is simply nonsensical.

Finally, the dogmatic insistence that addicts hit bottom is often used to excuse poor treatment. Treaters who are unable to help often scold addicts by telling them that they just aren’t ready yet and that they should come back once they’ve hit bottom and become ready to do the work. This is little more than a convenient dodge for ineffectual care, and a needless burden to place on the shoulders of addicts.

Alcoholics Anonymous has been instrumental in the widespread adoption of many such myths. The organization’s Twelve Steps, its expressions, and unique lexicon have found their way into the public discourse in a way that few other “brands” could ever match. So ingrained are these ideas, in fact, that many Americans would be hard-pressed to identify which came from AA and which from scientific investigation.

Alcoholics Anonymous has been instrumental in the widespread adoption of many such myths. The organization’s Twelve Steps, its expressions, and unique lexicon have found their way into the public discourse in a way that few other “brands” could ever match. So ingrained are these ideas, in fact, that many Americans would be hard-pressed to identify which came from AA and which from scientific investigation.The unfortunate part of this cultural penetration is that many addiction myths are harmful or even destructive, perpetuating false ideas about who addicts are, what addiction is, and what is needed to quit for good. In this chapter, I’d like to take a look at a few of these myths and examine some of the ways they impair efforts at adopting a more effective approach.

MYTH #1: YOU HAVE TO “HIT BOTTOM” BEFORE YOU CAN GET WELL

This common myth essentially says that an addict needs to reach a point of absolute loss or despair before he or she can begin to climb back toward a safe and productive life.

The most common objection to this myth is simple logic: nobody can possibly know where their “bottom” is until they identify it in retrospect. One person’s lowest point could be a night on the street, while another’s could be a bad day at work or even a small personal humiliation. It’s not unusual for one “bottom” to make way for another following a relapse. Without a clear definition, this is a concept that could be useful only in hindsight, if it is useful at all.

A bigger problem with this notion is the idea that addiction is in some fundamental way just a matter of stubbornness or stupidity—that is, addicts cannot recover until they are shown the consequences of their actions in a forceful enough way. This is a dressed-up version of the idea that addiction is a conscious choice and that stopping is a matter of recognizing the damage it causes. I have said it before, but it bears repeating: if consequences alone were enough to make someone stop repeating an addictive behavior, there would be no addicts. One of the defining agonies of addiction is that people can’t stop despite being well aware of the devastating consequences. That millions of people who have lost their jobs, marriages, and families are still unable to quit should be a clear indication that loss and despair, even in overwhelming quantities, aren’t enough to cure addiction. Conversely, many addicts stop their behavior at a point where they have not hit bottom in any sense.

There is a moralistic subtext at work here as well. The notion that addicts have to hit bottom suggests that they are too selfish to quit until they have paid a steep enough personal price. Once again we get an echo of the medieval notion of penance here: through suffering comes purity. Addicts no more need to experience devastating personal loss than does anyone else with a problem. Yes, it can be useful when a single moment helps to crystallize that one has a problem, but the fantasy that this moment must be especially painful is simply nonsensical.

Finally, the dogmatic insistence that addicts hit bottom is often used to excuse poor treatment. Treaters who are unable to help often scold addicts by telling them that they just aren’t ready yet and that they should come back once they’ve hit bottom and become ready to do the work. This is little more than a convenient dodge for ineffectual care, and a needless burden to place on the shoulders of addicts.

by Dr. Lance Dodes and Zachary Dodes, Salon | Read more:

Image: DonNichols via iStock/SalonSaturday, April 5, 2014

Just Cheer, Baby

Lacy T. was born to cheer. When she dances, she moves at the speed of a shook-up pompom. When she talks, it's in a peppy Southern drawl that makes everything sound as sweet as sugar. And when she poses, she is the image of a classic pinup: big hair, tiny waist and full lips that part to reveal a megawatt smile.

Naturally, when Lacy auditioned for the Oakland Raiderettes a year ago, she made the squad. And the Raiderettes quickly set to work remaking her in their image. She would be known exclusively by her first name and last initial -- a tradition across the NFL, ostensibly designed to protect its sideline stars from prying fans. The squad director handed Lacy, now 28, a sparkling pirate-inspired crop top, a copy of the team's top-secret "bible" -- which guides Raiderettes in everything from folding a dinner napkin correctly to spurning the advances of a married Raiders player -- and specific instructions for maintaining a head-to-toe Raiderettes look. The team presented Lacy with a photograph of herself next to a shot of actress Rachel McAdams, who would serve as Lacy's "celebrity hairstyle look-alike." Lacy was mandated to expertly mimic McAdams' light reddish-brown shade and 11/2-inch-diameter curls, starting with a $150 dye job at a squad-approved salon. Her fingers and toes were to be french-manicured at all times. Her skin was to maintain an artificial sun-kissed hue into the winter months. Her thighs would always be covered in dancing tights, and false lashes would be perpetually glued to her eyelids. Periodically, she'd have to step on a scale to prove that her weight had not inched more than 4 pounds above her 103-pound baseline.

Naturally, when Lacy auditioned for the Oakland Raiderettes a year ago, she made the squad. And the Raiderettes quickly set to work remaking her in their image. She would be known exclusively by her first name and last initial -- a tradition across the NFL, ostensibly designed to protect its sideline stars from prying fans. The squad director handed Lacy, now 28, a sparkling pirate-inspired crop top, a copy of the team's top-secret "bible" -- which guides Raiderettes in everything from folding a dinner napkin correctly to spurning the advances of a married Raiders player -- and specific instructions for maintaining a head-to-toe Raiderettes look. The team presented Lacy with a photograph of herself next to a shot of actress Rachel McAdams, who would serve as Lacy's "celebrity hairstyle look-alike." Lacy was mandated to expertly mimic McAdams' light reddish-brown shade and 11/2-inch-diameter curls, starting with a $150 dye job at a squad-approved salon. Her fingers and toes were to be french-manicured at all times. Her skin was to maintain an artificial sun-kissed hue into the winter months. Her thighs would always be covered in dancing tights, and false lashes would be perpetually glued to her eyelids. Periodically, she'd have to step on a scale to prove that her weight had not inched more than 4 pounds above her 103-pound baseline.

Long before Lacy's boots ever hit the gridiron grass, "I was just hustling," she says. "Very early on, I was spending money like crazy." The salon visits, the makeup, the eyelashes, the tights were almost exclusively paid out of her own pocket. The finishing touch of the Raiderettes' onboarding process was a contract requiring Lacy to attend thrice-weekly practices, dozens of public appearances, photo shoots, fittings and nine-hour shifts at Raiders home games, all in return for a lump sum of $1,250 at the conclusion of the season. (A few days before she filed suit, the team increased her pay to $2,780.) All rights to Lacy's image were surrendered to the Raiders. With fines for everything from forgetting pompoms to gaining weight, the handbook warned that it was entirely possible to "find yourself with no salary at all at the end of the season."

Like hundreds of women who have cheered for the Raiders since 1961, Lacy signed the contract. Unlike the rest of them, she also showed it to a lawyer.

Naturally, when Lacy auditioned for the Oakland Raiderettes a year ago, she made the squad. And the Raiderettes quickly set to work remaking her in their image. She would be known exclusively by her first name and last initial -- a tradition across the NFL, ostensibly designed to protect its sideline stars from prying fans. The squad director handed Lacy, now 28, a sparkling pirate-inspired crop top, a copy of the team's top-secret "bible" -- which guides Raiderettes in everything from folding a dinner napkin correctly to spurning the advances of a married Raiders player -- and specific instructions for maintaining a head-to-toe Raiderettes look. The team presented Lacy with a photograph of herself next to a shot of actress Rachel McAdams, who would serve as Lacy's "celebrity hairstyle look-alike." Lacy was mandated to expertly mimic McAdams' light reddish-brown shade and 11/2-inch-diameter curls, starting with a $150 dye job at a squad-approved salon. Her fingers and toes were to be french-manicured at all times. Her skin was to maintain an artificial sun-kissed hue into the winter months. Her thighs would always be covered in dancing tights, and false lashes would be perpetually glued to her eyelids. Periodically, she'd have to step on a scale to prove that her weight had not inched more than 4 pounds above her 103-pound baseline.

Naturally, when Lacy auditioned for the Oakland Raiderettes a year ago, she made the squad. And the Raiderettes quickly set to work remaking her in their image. She would be known exclusively by her first name and last initial -- a tradition across the NFL, ostensibly designed to protect its sideline stars from prying fans. The squad director handed Lacy, now 28, a sparkling pirate-inspired crop top, a copy of the team's top-secret "bible" -- which guides Raiderettes in everything from folding a dinner napkin correctly to spurning the advances of a married Raiders player -- and specific instructions for maintaining a head-to-toe Raiderettes look. The team presented Lacy with a photograph of herself next to a shot of actress Rachel McAdams, who would serve as Lacy's "celebrity hairstyle look-alike." Lacy was mandated to expertly mimic McAdams' light reddish-brown shade and 11/2-inch-diameter curls, starting with a $150 dye job at a squad-approved salon. Her fingers and toes were to be french-manicured at all times. Her skin was to maintain an artificial sun-kissed hue into the winter months. Her thighs would always be covered in dancing tights, and false lashes would be perpetually glued to her eyelids. Periodically, she'd have to step on a scale to prove that her weight had not inched more than 4 pounds above her 103-pound baseline.Long before Lacy's boots ever hit the gridiron grass, "I was just hustling," she says. "Very early on, I was spending money like crazy." The salon visits, the makeup, the eyelashes, the tights were almost exclusively paid out of her own pocket. The finishing touch of the Raiderettes' onboarding process was a contract requiring Lacy to attend thrice-weekly practices, dozens of public appearances, photo shoots, fittings and nine-hour shifts at Raiders home games, all in return for a lump sum of $1,250 at the conclusion of the season. (A few days before she filed suit, the team increased her pay to $2,780.) All rights to Lacy's image were surrendered to the Raiders. With fines for everything from forgetting pompoms to gaining weight, the handbook warned that it was entirely possible to "find yourself with no salary at all at the end of the season."

Like hundreds of women who have cheered for the Raiders since 1961, Lacy signed the contract. Unlike the rest of them, she also showed it to a lawyer.

by Amanda Hess, ESPN | Read more:

Image: Chris McPherson

New York 2050: Connected, But Alone

There are so many of us now.

Two centuries ago, the urban bourgeoisie of Haussmann's Paris used the grands boulevards, the shopping arcades, as the stage on which to perform the identities they had chosen for themselves. We are no longer so limited.

People like us don't use streets. We can, we must, use space for houses. The broad sidewalks of Madison Avenue, the soft green of Central Park: all these, if we see them at all, are only shadows between skyscrapers: patches between the towers that have taken the place of crosswalks, of trees.

People like us don't use streets. We can, we must, use space for houses. The broad sidewalks of Madison Avenue, the soft green of Central Park: all these, if we see them at all, are only shadows between skyscrapers: patches between the towers that have taken the place of crosswalks, of trees.

After all, we don't need them. Social media – now a quaintly antiquarian term, like “speakeasy” or “rave” – has been supplanted by an even bolder form of avatar-making. People like us needn't leave the house, after all. We send our proxy-selves by video or by holograph to do our bidding for us. Selves we can design, control. The Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard once analysed the anxiety of choice, of the dizziness engendered by an infinite number of possibilities. “Because it is possible to create,” he wrote, “creating one’s self, willing to be one’s self … one has anxiety. One would have no anxiety if there were no possibility whatever.” We know this is false. Of course we can create ourselves. We can look, act, enchant others, any way we like. We make ourselves in our own images.

At least, people like us do.

People like us have no limits. With so many avatars, we have no fear of missing out. We can be everywhere, every time. We simultaneously attend cocktail parties, dinners, fashionable literary readings, while going on five or ten dates with five or ten different men, who may or may not be on dates with as many women. All it takes is a click, and we've grown adept at multi-tasking. We sit within our white walls, in our windowless rooms, and project onto the barest of surfaces the most dizzying imagined backgrounds: Fifth Avenue as it once was, the Rainbow Room still intact, Coney Island before it sank into the sea. We project our friends and lovers, as they want us to see them, and know that somewhere, on their ceilings, we exist: the way we've always wanted to be.

The technology was invented in Silicon Valley, but it was in New York that it first caught on. In New York, where we were most wild for self-invention, where we were most afraid of missing out, where we were so afraid of being only one, lost in a crowd.

We fill up our hard drives with as many avatars, as many images, as we can afford. Demand has driven up the price of computer memory, and now this is where the majority of our money goes. The richest can afford as many selves as they like – any and all genders, appearances, orientations; our celebrities attend as many as a hundred parties at once. Though most of us still have to choose. We might have five or six avatars, if we're comfortably middle-class.

Still, we worry we've chosen wrong.

by Tara Isabella Burton, BBC | Read more:

Two centuries ago, the urban bourgeoisie of Haussmann's Paris used the grands boulevards, the shopping arcades, as the stage on which to perform the identities they had chosen for themselves. We are no longer so limited.

People like us don't use streets. We can, we must, use space for houses. The broad sidewalks of Madison Avenue, the soft green of Central Park: all these, if we see them at all, are only shadows between skyscrapers: patches between the towers that have taken the place of crosswalks, of trees.

People like us don't use streets. We can, we must, use space for houses. The broad sidewalks of Madison Avenue, the soft green of Central Park: all these, if we see them at all, are only shadows between skyscrapers: patches between the towers that have taken the place of crosswalks, of trees.After all, we don't need them. Social media – now a quaintly antiquarian term, like “speakeasy” or “rave” – has been supplanted by an even bolder form of avatar-making. People like us needn't leave the house, after all. We send our proxy-selves by video or by holograph to do our bidding for us. Selves we can design, control. The Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard once analysed the anxiety of choice, of the dizziness engendered by an infinite number of possibilities. “Because it is possible to create,” he wrote, “creating one’s self, willing to be one’s self … one has anxiety. One would have no anxiety if there were no possibility whatever.” We know this is false. Of course we can create ourselves. We can look, act, enchant others, any way we like. We make ourselves in our own images.

At least, people like us do.

People like us have no limits. With so many avatars, we have no fear of missing out. We can be everywhere, every time. We simultaneously attend cocktail parties, dinners, fashionable literary readings, while going on five or ten dates with five or ten different men, who may or may not be on dates with as many women. All it takes is a click, and we've grown adept at multi-tasking. We sit within our white walls, in our windowless rooms, and project onto the barest of surfaces the most dizzying imagined backgrounds: Fifth Avenue as it once was, the Rainbow Room still intact, Coney Island before it sank into the sea. We project our friends and lovers, as they want us to see them, and know that somewhere, on their ceilings, we exist: the way we've always wanted to be.

The technology was invented in Silicon Valley, but it was in New York that it first caught on. In New York, where we were most wild for self-invention, where we were most afraid of missing out, where we were so afraid of being only one, lost in a crowd.

We fill up our hard drives with as many avatars, as many images, as we can afford. Demand has driven up the price of computer memory, and now this is where the majority of our money goes. The richest can afford as many selves as they like – any and all genders, appearances, orientations; our celebrities attend as many as a hundred parties at once. Though most of us still have to choose. We might have five or six avatars, if we're comfortably middle-class.

Still, we worry we've chosen wrong.

by Tara Isabella Burton, BBC | Read more:

Image: Science Photo Library

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)