For as long as the environment has existed, it’s been in crisis. Nature has always been a focus of human thought and action, of course, but it wasn’t until pesticides and pollution started clouding the horizon that something called “the environment” emerged as a matter of public concern.

In 1960s and 1970s America, dystopian images provoked anxiety about the costs of unprecedented prosperity: smog thick enough to hide skylines from view, waste seeping into suburban backyards, rivers so polluted they burst into flames, cars lined up at gas stations amid shortages, chemical weapons that could defoliate entire forests. Economists and ecologists alike forecasted doom, warning that humanity was running up against natural limits to growth, extinction crises, and population explosions.

In 1960s and 1970s America, dystopian images provoked anxiety about the costs of unprecedented prosperity: smog thick enough to hide skylines from view, waste seeping into suburban backyards, rivers so polluted they burst into flames, cars lined up at gas stations amid shortages, chemical weapons that could defoliate entire forests. Economists and ecologists alike forecasted doom, warning that humanity was running up against natural limits to growth, extinction crises, and population explosions.

But the apocalypse didn’t happen. The threat that the environment seemingly posed to economic growth and human well-being faded from view; relieved to have vanquished the environmental foe, many rushed to declare themselves its friends instead.

Four decades later, everyone’s an environmentalist — and yet the environment appears to be in worse shape than ever. The problems of the seventies are back with a vengeance, often transposed into new landscapes, and new ones have joined them. Species we hardly knew existed are dying off en masse; oceans are acidifying in what sounds like the plot of a second-rate horror movie; numerous fisheries have collapsed or are on the brink; freshwater supplies are scarce in regions home to half the world’s population; agricultural land is exhausted of nutrients; forests are being leveled at staggering rates; and, of course, climate change looms over all.

These aren’t issues that can be fixed by slapping a filter on a smokestack. They’re certainly not about hugging trees or hating people. To put it bluntly, we’re confronted with the fact that human activity has transformed the entire planet in ways that are now threatening the way we inhabit it — some of us far more than others. And it’s not particularly helpful to talk in generalities: the idea that The Environment is some entity that can be fixed with A Solution is part of the problem.

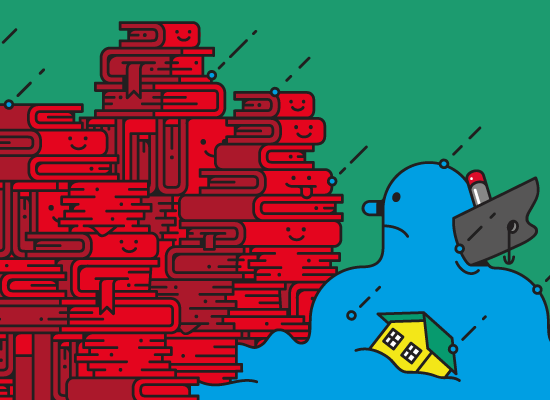

The category “environmental problems” contains multitudes, and their solutions don’t always line up: water shortages in Phoenix are a different matter than air pollution in Los Angeles, disappearing wetlands in Louisiana, or growing accumulations of atmospheric carbon. So instead of laying out some kind of template for a sustainable future, I argue that there’s no way to get there without tackling environmentalism’s old stumbling blocks: consumption and jobs. And the way to do that is through a universal basic income. (...)

It’s hard to think of many things more disingenuous than arguing that addressing environmental issues will impose unacceptable restrictions on the American standard of living while simultaneously promoting austerity measures — yet that attitude is pervasive in mainstream political discourse.

And while having stuff doesn’t make you a miserable soulless materialist, as some of the shriller anti-consumerist rhetoric would suggest, it doesn’t necessarily make you happier, either. Rather, the “status treadmill” frequently does the opposite: fueling anxiety, inadequacy, and debt under the banner of democracy and freedom. Meanwhile, consumer guilt has led to an explosion in “green” products — recycled toilet paper, organic T-shirts, all-natural detergents — but most do little more than greenwash the same old stuff, bestowing a sheen of virtue on their users, suggesting personal choices will save the planet. But the individual agonizing that constitutes consumer politics isn’t going to get around the fact that the global economy depends on more or less indefinitely expanding consumption. In fact, consumption has come full circle and become virtuous: protesting sweatshops and ranting about exploitation is passé; buying gadgets is the new way to lift people out of poverty. And so it’s not just workers who are threatened with jobs blackmail — we’re all threatened with consumption blackmail, wherein consuming less will put millions out of work worldwide and crash the global economy. Even our trash is creating jobs somewhere. (...)

In 1960s and 1970s America, dystopian images provoked anxiety about the costs of unprecedented prosperity: smog thick enough to hide skylines from view, waste seeping into suburban backyards, rivers so polluted they burst into flames, cars lined up at gas stations amid shortages, chemical weapons that could defoliate entire forests. Economists and ecologists alike forecasted doom, warning that humanity was running up against natural limits to growth, extinction crises, and population explosions.

In 1960s and 1970s America, dystopian images provoked anxiety about the costs of unprecedented prosperity: smog thick enough to hide skylines from view, waste seeping into suburban backyards, rivers so polluted they burst into flames, cars lined up at gas stations amid shortages, chemical weapons that could defoliate entire forests. Economists and ecologists alike forecasted doom, warning that humanity was running up against natural limits to growth, extinction crises, and population explosions.But the apocalypse didn’t happen. The threat that the environment seemingly posed to economic growth and human well-being faded from view; relieved to have vanquished the environmental foe, many rushed to declare themselves its friends instead.

Four decades later, everyone’s an environmentalist — and yet the environment appears to be in worse shape than ever. The problems of the seventies are back with a vengeance, often transposed into new landscapes, and new ones have joined them. Species we hardly knew existed are dying off en masse; oceans are acidifying in what sounds like the plot of a second-rate horror movie; numerous fisheries have collapsed or are on the brink; freshwater supplies are scarce in regions home to half the world’s population; agricultural land is exhausted of nutrients; forests are being leveled at staggering rates; and, of course, climate change looms over all.

These aren’t issues that can be fixed by slapping a filter on a smokestack. They’re certainly not about hugging trees or hating people. To put it bluntly, we’re confronted with the fact that human activity has transformed the entire planet in ways that are now threatening the way we inhabit it — some of us far more than others. And it’s not particularly helpful to talk in generalities: the idea that The Environment is some entity that can be fixed with A Solution is part of the problem.

The category “environmental problems” contains multitudes, and their solutions don’t always line up: water shortages in Phoenix are a different matter than air pollution in Los Angeles, disappearing wetlands in Louisiana, or growing accumulations of atmospheric carbon. So instead of laying out some kind of template for a sustainable future, I argue that there’s no way to get there without tackling environmentalism’s old stumbling blocks: consumption and jobs. And the way to do that is through a universal basic income. (...)

It’s hard to think of many things more disingenuous than arguing that addressing environmental issues will impose unacceptable restrictions on the American standard of living while simultaneously promoting austerity measures — yet that attitude is pervasive in mainstream political discourse.

And while having stuff doesn’t make you a miserable soulless materialist, as some of the shriller anti-consumerist rhetoric would suggest, it doesn’t necessarily make you happier, either. Rather, the “status treadmill” frequently does the opposite: fueling anxiety, inadequacy, and debt under the banner of democracy and freedom. Meanwhile, consumer guilt has led to an explosion in “green” products — recycled toilet paper, organic T-shirts, all-natural detergents — but most do little more than greenwash the same old stuff, bestowing a sheen of virtue on their users, suggesting personal choices will save the planet. But the individual agonizing that constitutes consumer politics isn’t going to get around the fact that the global economy depends on more or less indefinitely expanding consumption. In fact, consumption has come full circle and become virtuous: protesting sweatshops and ranting about exploitation is passé; buying gadgets is the new way to lift people out of poverty. And so it’s not just workers who are threatened with jobs blackmail — we’re all threatened with consumption blackmail, wherein consuming less will put millions out of work worldwide and crash the global economy. Even our trash is creating jobs somewhere. (...)

A “green economy” can’t just be one that makes “green” versions of the same stuff, or one that makes solar panels in addition to SUVs. Eco-Keynesianism in the form of public works projects can be temporarily helpful in building light rail systems and efficient infrastructure, weatherizing homes, and restoring ecosystems — and to be sure, there’s a lot of work to be done in those areas. But a spike in green jobs doesn’t tell us much about how to provide for everyone without creating jobs by perpetually expanding production. The problem isn’t that every detail of the green-jobs economy isn’t laid out in full — calls for green jobs are meant to recognize the fraught history of labor-environmentalist relations, and to signify a commitment to ensuring that sustainability doesn’t come at the expense of working communities. The problem is that the vision they call forth isn’t a projection of the future so much as a reflection of the past — most visions of a “new economy” look a whole lot like the same old one. Such visions reveal a hope that climate change will be our generation’s New Deal or World War II, vaulting us out of hard times into a new era of widespread prosperity.

by Alyssa Battistoni, Jacobin | Read more:

Image: Edward Carvalho-Monaghan