Friday, January 2, 2015

Why The Mona Lisa Stands Out

[ed. See also: The Art World's Patron Satan]

In 1993 a psychologist, James Cutting, visited the Musée d’Orsay in Paris to see Renoir’s picture of Parisians at play, “Bal du Moulin de la Galette”, considered one of the greatest works of impressionism. Instead, he found himself magnetically drawn to a painting in the next room: an enchanting, mysterious view of snow on Parisian rooftops. He had never seen it before, nor heard of its creator, Gustave Caillebotte.

That was what got him thinking.

That was what got him thinking.

Have you ever fallen for a novel and been amazed not to find it on lists of great books? Or walked around a sculpture renowned as a classic, struggling to see what the fuss is about? If so, you’ve probably pondered the question Cutting asked himself that day: how does a work of art come to be considered great? (...)

The process described by Cutting evokes a principle that the sociologist Duncan Watts calls “cumulative advantage”: once a thing becomes popular, it will tend to become more popular still. A few years ago, Watts, who is employed by Microsoft to study the dynamics of social networks, had a similar experience to Cutting in another Paris museum. After queuing to see the “Mona Lisa” in its climate-controlled bulletproof box at the Louvre, he came away puzzled: why was it considered so superior to the three other Leonardos in the previous chamber, to which nobody seemed to be paying the slightest attention?

When Watts looked into the history of “the greatest painting of all time”, he discovered that, for most of its life, the “Mona Lisa” languished in relative obscurity. In the 1850s, Leonardo da Vinci was considered no match for giants of Renaissance art like Titian and Raphael, whose works were worth almost ten times as much as the “Mona Lisa”. It was only in the 20th century that Leonardo’s portrait of his patron’s wife rocketed to the number-one spot. What propelled it there wasn’t a scholarly re-evaluation, but a burglary.

In 1911 a maintenance worker at the Louvre walked out of the museum with the “Mona Lisa” hidden under his smock. Parisians were aghast at the theft of a painting to which, until then, they had paid little attention. When the museum reopened, people queued to see the gap where the “Mona Lisa” had once hung in a way they had never done for the painting itself. The police were stumped. At one point, a terrified Pablo Picasso was called in for questioning. But the “Mona Lisa” wasn’t recovered until two years later when the thief, an Italian carpenter called Vincenzo Peruggia, was caught trying to sell it to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

The French public was electrified. The Italians hailed Peruggia as a patriot who wanted to return the painting home. Newspapers around the world reproduced it, making it the first work of art to achieve global fame. From then on, the “Mona Lisa” came to represent Western culture itself. In 1919, when Marcel Duchamp wanted to perform a symbolic defacing of high art, he put a goatee on the “Mona Lisa”, which only reinforced its status in the popular mind as the epitome of great art (or as the critic Kenneth Clark later put it, “the supreme example of perfection”). Throughout the 20th century, musicians, advertisers and film-makers used the painting’s fame for their own purposes, while the painting, in Watts’s words, “used them back”. Peruggia failed to repatriate the “Mona Lisa”, but he succeeded in making it an icon.

Although many have tried, it does seem improbable that the painting’s unique status can be attributed entirely to the quality of its brushstrokes. It has been said that the subject’s eyes follow the viewer around the room. But as the painting’s biographer, Donald Sassoon, drily notes, “In reality the effect can be obtained from any portrait.” Duncan Watts proposes that the “Mona Lisa” is merely an extreme example of a general rule. Paintings, poems and pop songs are buoyed or sunk by random events or preferences that turn into waves of influence, rippling down the generations.

by Ian Leslie, Intelligent Life | Read more:

Image: Eyevine

In 1993 a psychologist, James Cutting, visited the Musée d’Orsay in Paris to see Renoir’s picture of Parisians at play, “Bal du Moulin de la Galette”, considered one of the greatest works of impressionism. Instead, he found himself magnetically drawn to a painting in the next room: an enchanting, mysterious view of snow on Parisian rooftops. He had never seen it before, nor heard of its creator, Gustave Caillebotte.

That was what got him thinking.

That was what got him thinking.Have you ever fallen for a novel and been amazed not to find it on lists of great books? Or walked around a sculpture renowned as a classic, struggling to see what the fuss is about? If so, you’ve probably pondered the question Cutting asked himself that day: how does a work of art come to be considered great? (...)

The process described by Cutting evokes a principle that the sociologist Duncan Watts calls “cumulative advantage”: once a thing becomes popular, it will tend to become more popular still. A few years ago, Watts, who is employed by Microsoft to study the dynamics of social networks, had a similar experience to Cutting in another Paris museum. After queuing to see the “Mona Lisa” in its climate-controlled bulletproof box at the Louvre, he came away puzzled: why was it considered so superior to the three other Leonardos in the previous chamber, to which nobody seemed to be paying the slightest attention?

When Watts looked into the history of “the greatest painting of all time”, he discovered that, for most of its life, the “Mona Lisa” languished in relative obscurity. In the 1850s, Leonardo da Vinci was considered no match for giants of Renaissance art like Titian and Raphael, whose works were worth almost ten times as much as the “Mona Lisa”. It was only in the 20th century that Leonardo’s portrait of his patron’s wife rocketed to the number-one spot. What propelled it there wasn’t a scholarly re-evaluation, but a burglary.

In 1911 a maintenance worker at the Louvre walked out of the museum with the “Mona Lisa” hidden under his smock. Parisians were aghast at the theft of a painting to which, until then, they had paid little attention. When the museum reopened, people queued to see the gap where the “Mona Lisa” had once hung in a way they had never done for the painting itself. The police were stumped. At one point, a terrified Pablo Picasso was called in for questioning. But the “Mona Lisa” wasn’t recovered until two years later when the thief, an Italian carpenter called Vincenzo Peruggia, was caught trying to sell it to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

The French public was electrified. The Italians hailed Peruggia as a patriot who wanted to return the painting home. Newspapers around the world reproduced it, making it the first work of art to achieve global fame. From then on, the “Mona Lisa” came to represent Western culture itself. In 1919, when Marcel Duchamp wanted to perform a symbolic defacing of high art, he put a goatee on the “Mona Lisa”, which only reinforced its status in the popular mind as the epitome of great art (or as the critic Kenneth Clark later put it, “the supreme example of perfection”). Throughout the 20th century, musicians, advertisers and film-makers used the painting’s fame for their own purposes, while the painting, in Watts’s words, “used them back”. Peruggia failed to repatriate the “Mona Lisa”, but he succeeded in making it an icon.

Although many have tried, it does seem improbable that the painting’s unique status can be attributed entirely to the quality of its brushstrokes. It has been said that the subject’s eyes follow the viewer around the room. But as the painting’s biographer, Donald Sassoon, drily notes, “In reality the effect can be obtained from any portrait.” Duncan Watts proposes that the “Mona Lisa” is merely an extreme example of a general rule. Paintings, poems and pop songs are buoyed or sunk by random events or preferences that turn into waves of influence, rippling down the generations.

by Ian Leslie, Intelligent Life | Read more:

Image: Eyevine

Toxic Detox Myths

Whether it’s cucumbers splashing into water or models sitting smugly next to a pile of vegetables, it’s tough not to be sucked in by the detox industry. The idea that you can wash away your calorific sins is the perfect antidote to our fast-food lifestyles and alcohol-lubricated social lives. But before you dust off that juicer or take the first tentative steps towards a colonic irrigation clinic, there’s something you should know: detoxing – the idea that you can flush your system of impurities and leave your organs squeaky clean and raring to go – is a scam. It’s a pseudo-medical concept designed to sell you things.

“Let’s be clear,” says Edzard Ernst, emeritus professor of complementary medicine at Exeter University, “there are two types of detox: one is respectable and the other isn’t.” The respectable one, he says, is the medical treatment of people with life-threatening drug addictions. “The other is the word being hijacked by entrepreneurs, quacks and charlatans to sell a bogus treatment that allegedly detoxifies your body of toxins you’re supposed to have accumulated.”

“Let’s be clear,” says Edzard Ernst, emeritus professor of complementary medicine at Exeter University, “there are two types of detox: one is respectable and the other isn’t.” The respectable one, he says, is the medical treatment of people with life-threatening drug addictions. “The other is the word being hijacked by entrepreneurs, quacks and charlatans to sell a bogus treatment that allegedly detoxifies your body of toxins you’re supposed to have accumulated.”

If toxins did build up in a way your body couldn’t excrete, he says, you’d likely be dead or in need of serious medical intervention. “The healthy body has kidneys, a liver, skin, even lungs that are detoxifying as we speak,” he says. “There is no known way – certainly not through detox treatments – to make something that works perfectly well in a healthy body work better.”

Much of the sales patter revolves around “toxins”: poisonous substances that you ingest or inhale. But it’s not clear exactly what these toxins are. If they were named they could be measured before and after treatment to test effectiveness. Yet, much like floaters in your eye, try to focus on these toxins and they scamper from view. In 2009, a network of scientists assembled by the UK charity Sense about Science contacted the manufacturers of 15 products sold in pharmacies and supermarkets that claimed to detoxify. The products ranged from dietary supplements to smoothies and shampoos. When the scientists asked for evidence behind the claims, not one of the manufacturers could define what they meant by detoxification, let alone name the toxins.

Yet, inexplicably, the shelves of health food stores are still packed with products bearing the word “detox” – it’s the marketing equivalent of drawing go-faster stripes on your car. You can buy detoxifying tablets, tinctures, tea bags, face masks, bath salts, hair brushes, shampoos, body gels and even hair straighteners. Yoga, luxury retreats, and massages will also all erroneously promise to detoxify. You can go on a seven-day detox diet and you’ll probably lose weight, but that’s nothing to do with toxins, it’s because you would have starved yourself for a week.

Then there’s colonic irrigation. Its proponents will tell you that mischievous plaques of impacted poo can lurk in your colon for months or years and pump disease-causing toxins back into your system. Pay them a small fee, though, and they’ll insert a hose up your bottom and wash them all away. Unfortunately for them – and possibly fortunately for you – no doctor has ever seen one of these mythical plaques, and many warn against having the procedure done, saying that it can perforate your bowel.

Other tactics are more insidious. Some colon-cleansing tablets contain a polymerising agent that turns your faeces into something like a plastic, so that when a massive rubbery poo snake slithers into your toilet you can stare back at it and feel vindicated in your purchase. Detoxing foot pads turn brown overnight with what manufacturers claim is toxic sludge drawn from your body. This sludge is nothing of the sort – a substance in the pads turns brown when it mixes with water from your sweat.

“It’s a scandal,” fumes Ernst. “It’s criminal exploitation of the gullible man on the street and it sort of keys into something that we all would love to have – a simple remedy that frees us of our sins, so to speak. It’s nice to think that it could exist but unfortunately it doesn’t.”

by Dara Mohammadi, The Guardian | Read more:

Image: Frederic J. Brown/AFP/Getty Images

“Let’s be clear,” says Edzard Ernst, emeritus professor of complementary medicine at Exeter University, “there are two types of detox: one is respectable and the other isn’t.” The respectable one, he says, is the medical treatment of people with life-threatening drug addictions. “The other is the word being hijacked by entrepreneurs, quacks and charlatans to sell a bogus treatment that allegedly detoxifies your body of toxins you’re supposed to have accumulated.”

“Let’s be clear,” says Edzard Ernst, emeritus professor of complementary medicine at Exeter University, “there are two types of detox: one is respectable and the other isn’t.” The respectable one, he says, is the medical treatment of people with life-threatening drug addictions. “The other is the word being hijacked by entrepreneurs, quacks and charlatans to sell a bogus treatment that allegedly detoxifies your body of toxins you’re supposed to have accumulated.”If toxins did build up in a way your body couldn’t excrete, he says, you’d likely be dead or in need of serious medical intervention. “The healthy body has kidneys, a liver, skin, even lungs that are detoxifying as we speak,” he says. “There is no known way – certainly not through detox treatments – to make something that works perfectly well in a healthy body work better.”

Much of the sales patter revolves around “toxins”: poisonous substances that you ingest or inhale. But it’s not clear exactly what these toxins are. If they were named they could be measured before and after treatment to test effectiveness. Yet, much like floaters in your eye, try to focus on these toxins and they scamper from view. In 2009, a network of scientists assembled by the UK charity Sense about Science contacted the manufacturers of 15 products sold in pharmacies and supermarkets that claimed to detoxify. The products ranged from dietary supplements to smoothies and shampoos. When the scientists asked for evidence behind the claims, not one of the manufacturers could define what they meant by detoxification, let alone name the toxins.

Yet, inexplicably, the shelves of health food stores are still packed with products bearing the word “detox” – it’s the marketing equivalent of drawing go-faster stripes on your car. You can buy detoxifying tablets, tinctures, tea bags, face masks, bath salts, hair brushes, shampoos, body gels and even hair straighteners. Yoga, luxury retreats, and massages will also all erroneously promise to detoxify. You can go on a seven-day detox diet and you’ll probably lose weight, but that’s nothing to do with toxins, it’s because you would have starved yourself for a week.

Then there’s colonic irrigation. Its proponents will tell you that mischievous plaques of impacted poo can lurk in your colon for months or years and pump disease-causing toxins back into your system. Pay them a small fee, though, and they’ll insert a hose up your bottom and wash them all away. Unfortunately for them – and possibly fortunately for you – no doctor has ever seen one of these mythical plaques, and many warn against having the procedure done, saying that it can perforate your bowel.

Other tactics are more insidious. Some colon-cleansing tablets contain a polymerising agent that turns your faeces into something like a plastic, so that when a massive rubbery poo snake slithers into your toilet you can stare back at it and feel vindicated in your purchase. Detoxing foot pads turn brown overnight with what manufacturers claim is toxic sludge drawn from your body. This sludge is nothing of the sort – a substance in the pads turns brown when it mixes with water from your sweat.

“It’s a scandal,” fumes Ernst. “It’s criminal exploitation of the gullible man on the street and it sort of keys into something that we all would love to have – a simple remedy that frees us of our sins, so to speak. It’s nice to think that it could exist but unfortunately it doesn’t.”

by Dara Mohammadi, The Guardian | Read more:

Image: Frederic J. Brown/AFP/Getty Images

13 Notes on the College Football Playoff

[ed. Go Ducks! Man, what a wipeout. Something of a trend across the SEC. Safe to say the new college football playoffs have been a great success so far.]

1. Florida State completely collapsed. You know what they say about pressure: it bursts pipes or creates diamonds. Or sometimes, when Oregon is running you to the limit of your football credit, it takes your diamonds, flushes them down the world's biggest pipes, and then stuffs you into the great sucking drain of history.

That is what happened when Florida State lost, 59-20, New Year's Day. It feels like a kind of duty to note, out of sportsmanship, just how monumental a thing ended in the Rose Bowl. The Seminoles had won 29 in a row, won two ACC titles and one national title, and garnered a Heisman Trophy for Jameis Winston. That all happened, and nothing can ever take that away from Florida State. Look, it's in a book and in the records and everything.

That is what happened when Florida State lost, 59-20, New Year's Day. It feels like a kind of duty to note, out of sportsmanship, just how monumental a thing ended in the Rose Bowl. The Seminoles had won 29 in a row, won two ACC titles and one national title, and garnered a Heisman Trophy for Jameis Winston. That all happened, and nothing can ever take that away from Florida State. Look, it's in a book and in the records and everything.

2. But that -- is that how you want it to end? The suspicions all along for the Seminoles this year were that they were skating along in a weak conference, aided and abetted by the longest string of fortuitous bounces and tips ever, and bailed out in key situations by the holy triumverate of Jameis, Nick O'Leary, and Rashad Greene. And it should have been so easy to call their bluff, and yet no one could, not Louisville, not Notre Dame, not Florida, not even Miami playing at home.

3. They were going to steal a title, and you were going to haaaaaaate how they did it.

4. Even at the half, you thought it was going to happen. FSU only trailed, 18-13, and was in prime position to do the dastardly thing it'd done all year long. The Seminoles were going to steal the train. They were going to run into the sunset with your horses and your children, and then Dalvin Cook fumbled, and Oregon scored. But there, at 25-13, right there, that's when Florida State would do that thing, and throw a few passes and get this back to a one-score game, and that's what they did, but then another Cook fumble.

5. Then Jameis Winston scrambled his way into his personal disaster meme.

Winston could try to do that a thousand times and fail to duplicate it. It is a piece of failure so perfect it is its own achievement. It is a spastic piece of randomness unlike any other in the entire scope of human history. And all joking aside, this is when you knew the game was over at 45-20: not because of the score, but because no one recovers from a line in the script like this.

by Spencer Hall, SBNation | Read more:

Image: Harry How/Getty Images and Giphy

1. Florida State completely collapsed. You know what they say about pressure: it bursts pipes or creates diamonds. Or sometimes, when Oregon is running you to the limit of your football credit, it takes your diamonds, flushes them down the world's biggest pipes, and then stuffs you into the great sucking drain of history.

That is what happened when Florida State lost, 59-20, New Year's Day. It feels like a kind of duty to note, out of sportsmanship, just how monumental a thing ended in the Rose Bowl. The Seminoles had won 29 in a row, won two ACC titles and one national title, and garnered a Heisman Trophy for Jameis Winston. That all happened, and nothing can ever take that away from Florida State. Look, it's in a book and in the records and everything.

That is what happened when Florida State lost, 59-20, New Year's Day. It feels like a kind of duty to note, out of sportsmanship, just how monumental a thing ended in the Rose Bowl. The Seminoles had won 29 in a row, won two ACC titles and one national title, and garnered a Heisman Trophy for Jameis Winston. That all happened, and nothing can ever take that away from Florida State. Look, it's in a book and in the records and everything.2. But that -- is that how you want it to end? The suspicions all along for the Seminoles this year were that they were skating along in a weak conference, aided and abetted by the longest string of fortuitous bounces and tips ever, and bailed out in key situations by the holy triumverate of Jameis, Nick O'Leary, and Rashad Greene. And it should have been so easy to call their bluff, and yet no one could, not Louisville, not Notre Dame, not Florida, not even Miami playing at home.

3. They were going to steal a title, and you were going to haaaaaaate how they did it.

4. Even at the half, you thought it was going to happen. FSU only trailed, 18-13, and was in prime position to do the dastardly thing it'd done all year long. The Seminoles were going to steal the train. They were going to run into the sunset with your horses and your children, and then Dalvin Cook fumbled, and Oregon scored. But there, at 25-13, right there, that's when Florida State would do that thing, and throw a few passes and get this back to a one-score game, and that's what they did, but then another Cook fumble.

5. Then Jameis Winston scrambled his way into his personal disaster meme.

Winston could try to do that a thousand times and fail to duplicate it. It is a piece of failure so perfect it is its own achievement. It is a spastic piece of randomness unlike any other in the entire scope of human history. And all joking aside, this is when you knew the game was over at 45-20: not because of the score, but because no one recovers from a line in the script like this.

Image: Harry How/Getty Images and Giphy

Thursday, January 1, 2015

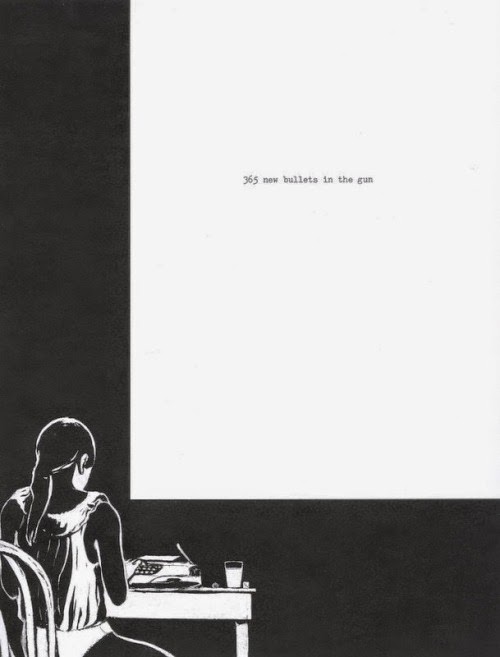

How to Write

I teach a Popular Criticism class to MFA students. I don’t actually have an MFA, but I am a professional, full-time writer who has been in this business for almost two decades, and I’ve written for a wide range of impressive print and online publications, the names of which you will hear and think, “Oh fuck, she’s the real deal.” Because I am the real deal. I tell my students that a lot, like when they interrupt me or roll their eyes at something I say because they’re young and only listen when old hippies are digressing about Gilles Deleuze’s notions of high capitalism’s infantilizing commodifications or some such horse shit.

Anyway, since Friday is our last class, and since I’m one of the only writers my students know who earns actual legal tender from her writing—instead of say, free copies of Ploughshares—they’re all dying to know how I do it. In fact, one of my students just sent me an email to that effect: “For the last class, I was wondering if you could give us a breakdown of your day-to-day schedule. How do you juggle all of your contracted assignments with your freelance stuff and everything else you do?”

Anyway, since Friday is our last class, and since I’m one of the only writers my students know who earns actual legal tender from her writing—instead of say, free copies of Ploughshares—they’re all dying to know how I do it. In fact, one of my students just sent me an email to that effect: “For the last class, I was wondering if you could give us a breakdown of your day-to-day schedule. How do you juggle all of your contracted assignments with your freelance stuff and everything else you do?”

Now, I’m not going to lie. It’s annoying, to have to take time out of my incredibly busy writing schedule in order to spell it all out for young people, just because they spend most of their daylight hours being urged by hoary old theorists in threadbare sweaters to write experimental fiction that will never sell. But I care deeply about the young—all of them, the world’s young—so of course I am humbled and honored to share the trade secrets embedded in my rigorous daily work schedule. Here we go:

Today, I woke up at 4 a.m. because one of my dogs was making a strange gulping sound. I sat for several minutes listening closely, wide awake, wondering if she wasn’t developing esophageal cancer or some other gruesome ailment that the pricey animal specialty hospital might guilt me into actually treating. I imagined sitting in the posh chill of their giant waiting room, the pricey coffee and tea machine humming away next to me, filling out forms instructing them to never crack my 10-year-old dog’s chest and do emergency open heart surgery if she starts coding. “Option 1: LET MY DOG DIE.” That’s one I had to check off and sign, over and over again, when my other, eight-year-old dog had an unexplained fever and it cost me $6000 to save her. The vet’s eyes would dart over my forms and the corners of her mouth would pinch slightly, and then she’d treat me like someone who might just yank the IV out of her dog’s leg and twist her neck at any minute, the Jack Bauer of budget-minded dog owners.

Anyway, right about now you’re starting to understand why the morning hours are so potent for a working writer: The mind spills over with expansive concepts and sweeping images that just cry out to be tapped in another scintillating essay or think piece.

Rather than get up and spoil my inspired revelry, though, I know to let these thoughts swirl and churn until they take a more coherent shape. My mind soon shifts to tallying up the costs of college for my stepson, who for some nutty reason applied to a wide range of insanely expensive private colleges on the East Coast. After I marvel over that sum for a while, I try adding together his costs with the costs of sending my two young daughters to college in ten years. Then I think about how we should probably try to pay off our credit cards and our home equity loan first, and THEN focus on coming up with this mammoth amount for college, and then of course we’ll be retiring right after that but we’ll still have 15 years left on our massive mortgage. “We’re never going to retire,” I think. “We’re going to have to keep working forever and ever and ever. And we can’t turn on the AC this summer. And we have to stop going out to our favorite Mexican restaurant every other week and drinking margaritas, which are an inexcusably expensive indulgence.” Old people problems, LOL.

Then I think about margaritas for a while. I think about how there should really be a breakfast margarita. Breakfast ‘Rita. Breakarita. Sunrise ‘Rita. Maybe with Chia seeds. I think about how I worked at Applebee’s when I was my stepson’s age. And he’s never even had a job. Ever! I think about how weird that is, that he’s never had a job, but he’s applying to colleges that cost $250k, all told. YOLO, I guess.

Then I think about how my black Applebee’s polo shirt always smelled like nachos because I didn’t wash it often enough. See how I was thinking about a smell? That’s how you know I’m a real artist and not some fucking hack who writes light verse for The New Yorker. Artists can conjure a stinky odor using only their raw powers of imagination and long-term memory. That’s also how you know it’s time to write.

by Heather Havrilesky, The Awl | Read more:

Image: Ed Yourdon

Anyway, since Friday is our last class, and since I’m one of the only writers my students know who earns actual legal tender from her writing—instead of say, free copies of Ploughshares—they’re all dying to know how I do it. In fact, one of my students just sent me an email to that effect: “For the last class, I was wondering if you could give us a breakdown of your day-to-day schedule. How do you juggle all of your contracted assignments with your freelance stuff and everything else you do?”

Anyway, since Friday is our last class, and since I’m one of the only writers my students know who earns actual legal tender from her writing—instead of say, free copies of Ploughshares—they’re all dying to know how I do it. In fact, one of my students just sent me an email to that effect: “For the last class, I was wondering if you could give us a breakdown of your day-to-day schedule. How do you juggle all of your contracted assignments with your freelance stuff and everything else you do?”Now, I’m not going to lie. It’s annoying, to have to take time out of my incredibly busy writing schedule in order to spell it all out for young people, just because they spend most of their daylight hours being urged by hoary old theorists in threadbare sweaters to write experimental fiction that will never sell. But I care deeply about the young—all of them, the world’s young—so of course I am humbled and honored to share the trade secrets embedded in my rigorous daily work schedule. Here we go:

Today, I woke up at 4 a.m. because one of my dogs was making a strange gulping sound. I sat for several minutes listening closely, wide awake, wondering if she wasn’t developing esophageal cancer or some other gruesome ailment that the pricey animal specialty hospital might guilt me into actually treating. I imagined sitting in the posh chill of their giant waiting room, the pricey coffee and tea machine humming away next to me, filling out forms instructing them to never crack my 10-year-old dog’s chest and do emergency open heart surgery if she starts coding. “Option 1: LET MY DOG DIE.” That’s one I had to check off and sign, over and over again, when my other, eight-year-old dog had an unexplained fever and it cost me $6000 to save her. The vet’s eyes would dart over my forms and the corners of her mouth would pinch slightly, and then she’d treat me like someone who might just yank the IV out of her dog’s leg and twist her neck at any minute, the Jack Bauer of budget-minded dog owners.

Anyway, right about now you’re starting to understand why the morning hours are so potent for a working writer: The mind spills over with expansive concepts and sweeping images that just cry out to be tapped in another scintillating essay or think piece.

Rather than get up and spoil my inspired revelry, though, I know to let these thoughts swirl and churn until they take a more coherent shape. My mind soon shifts to tallying up the costs of college for my stepson, who for some nutty reason applied to a wide range of insanely expensive private colleges on the East Coast. After I marvel over that sum for a while, I try adding together his costs with the costs of sending my two young daughters to college in ten years. Then I think about how we should probably try to pay off our credit cards and our home equity loan first, and THEN focus on coming up with this mammoth amount for college, and then of course we’ll be retiring right after that but we’ll still have 15 years left on our massive mortgage. “We’re never going to retire,” I think. “We’re going to have to keep working forever and ever and ever. And we can’t turn on the AC this summer. And we have to stop going out to our favorite Mexican restaurant every other week and drinking margaritas, which are an inexcusably expensive indulgence.” Old people problems, LOL.

Then I think about margaritas for a while. I think about how there should really be a breakfast margarita. Breakfast ‘Rita. Breakarita. Sunrise ‘Rita. Maybe with Chia seeds. I think about how I worked at Applebee’s when I was my stepson’s age. And he’s never even had a job. Ever! I think about how weird that is, that he’s never had a job, but he’s applying to colleges that cost $250k, all told. YOLO, I guess.

Then I think about how my black Applebee’s polo shirt always smelled like nachos because I didn’t wash it often enough. See how I was thinking about a smell? That’s how you know I’m a real artist and not some fucking hack who writes light verse for The New Yorker. Artists can conjure a stinky odor using only their raw powers of imagination and long-term memory. That’s also how you know it’s time to write.

Image: Ed Yourdon

Wednesday, December 31, 2014

Hawaiian Dreamers

Alexander Tikhomirov

The Wreck of the Kulluk

On the morning of Dec. 21, as the Aiviq and Kulluk crews prepared to depart on the three-week journey back to Seattle, Shell’s new warranty surveyor took careful note of the certificates for the steel shackles that would connect the two vessels and bear the dead weight of the giant Kulluk — without noticing that they had been replaced with theoretically sturdier shackles of unknown origin. He examined the shackles but had little means by which to test their strength. He did not ask the crew to rotate the shackles, as one might rotate tires on a car. He did not consider it part of his job, he would tell Coast Guard investigators, to examine whether Shell’s overall plan to cross the Gulf of Alaska made any sense.

The Aiviq pulled the Kulluk away just after lunchtime. The Aiviq’s usual captain was on vacation for the holidays, as were Slaiby and other members of Shell’s senior Alaska staff. The rest of the tug’s crew had limited experience in the operation of the new, complex vessel. Onboard the Kulluk was a skeleton crew of 18 men, along for the ride in large part because of an inconvenience of the rig’s flag of convenience. The Kulluk was registered in the Marshall Islands, the same country where BP’s contractors had registered the Deepwater Horizon, and the Marshall Islands required that the rig be manned, even when under tow. The new captain of the Aiviq, Jon Skoglund, proposed aiming straight for the Seattle area, a direct and faster “great circle” route that would leave the two ships alone in the middle of the North Pacific but would avoid the shoals, rocks and waves of the Alaskan coast. There would be no shore to crash into. They could lengthen the towline for better shock absorption and would have room to move if problems arose. The idea was dropped because the Kulluk’s 18 crew members would then be out of range of Coast Guard search-and-rescue helicopters. Perversely, a flag of convenience, seen as a way to avoid government regulation, had Shell seeking a government safety net — and a longer, more dangerous, near-shore route.

The Aiviq pulled the Kulluk away just after lunchtime. The Aiviq’s usual captain was on vacation for the holidays, as were Slaiby and other members of Shell’s senior Alaska staff. The rest of the tug’s crew had limited experience in the operation of the new, complex vessel. Onboard the Kulluk was a skeleton crew of 18 men, along for the ride in large part because of an inconvenience of the rig’s flag of convenience. The Kulluk was registered in the Marshall Islands, the same country where BP’s contractors had registered the Deepwater Horizon, and the Marshall Islands required that the rig be manned, even when under tow. The new captain of the Aiviq, Jon Skoglund, proposed aiming straight for the Seattle area, a direct and faster “great circle” route that would leave the two ships alone in the middle of the North Pacific but would avoid the shoals, rocks and waves of the Alaskan coast. There would be no shore to crash into. They could lengthen the towline for better shock absorption and would have room to move if problems arose. The idea was dropped because the Kulluk’s 18 crew members would then be out of range of Coast Guard search-and-rescue helicopters. Perversely, a flag of convenience, seen as a way to avoid government regulation, had Shell seeking a government safety net — and a longer, more dangerous, near-shore route.

Skoglund was so concerned as he began his first Gulf of Alaska tow that he sent an email to the chief Kulluk mariner on the other side of the towline. “To be blunt,” he wrote, “I believe that this length of tow, at this time of year, in this location, with our current routing guarantees an ass kicking.”(...)

The Aiviq pulled the Kulluk away just after lunchtime. The Aiviq’s usual captain was on vacation for the holidays, as were Slaiby and other members of Shell’s senior Alaska staff. The rest of the tug’s crew had limited experience in the operation of the new, complex vessel. Onboard the Kulluk was a skeleton crew of 18 men, along for the ride in large part because of an inconvenience of the rig’s flag of convenience. The Kulluk was registered in the Marshall Islands, the same country where BP’s contractors had registered the Deepwater Horizon, and the Marshall Islands required that the rig be manned, even when under tow. The new captain of the Aiviq, Jon Skoglund, proposed aiming straight for the Seattle area, a direct and faster “great circle” route that would leave the two ships alone in the middle of the North Pacific but would avoid the shoals, rocks and waves of the Alaskan coast. There would be no shore to crash into. They could lengthen the towline for better shock absorption and would have room to move if problems arose. The idea was dropped because the Kulluk’s 18 crew members would then be out of range of Coast Guard search-and-rescue helicopters. Perversely, a flag of convenience, seen as a way to avoid government regulation, had Shell seeking a government safety net — and a longer, more dangerous, near-shore route.

The Aiviq pulled the Kulluk away just after lunchtime. The Aiviq’s usual captain was on vacation for the holidays, as were Slaiby and other members of Shell’s senior Alaska staff. The rest of the tug’s crew had limited experience in the operation of the new, complex vessel. Onboard the Kulluk was a skeleton crew of 18 men, along for the ride in large part because of an inconvenience of the rig’s flag of convenience. The Kulluk was registered in the Marshall Islands, the same country where BP’s contractors had registered the Deepwater Horizon, and the Marshall Islands required that the rig be manned, even when under tow. The new captain of the Aiviq, Jon Skoglund, proposed aiming straight for the Seattle area, a direct and faster “great circle” route that would leave the two ships alone in the middle of the North Pacific but would avoid the shoals, rocks and waves of the Alaskan coast. There would be no shore to crash into. They could lengthen the towline for better shock absorption and would have room to move if problems arose. The idea was dropped because the Kulluk’s 18 crew members would then be out of range of Coast Guard search-and-rescue helicopters. Perversely, a flag of convenience, seen as a way to avoid government regulation, had Shell seeking a government safety net — and a longer, more dangerous, near-shore route.Skoglund was so concerned as he began his first Gulf of Alaska tow that he sent an email to the chief Kulluk mariner on the other side of the towline. “To be blunt,” he wrote, “I believe that this length of tow, at this time of year, in this location, with our current routing guarantees an ass kicking.”(...)

By the early, dark hours of Dec. 29, the unified command was convinced that lives were at risk, and it dispatched two Coast Guard Jayhawk helicopters to evacuate the 18 increasingly anxious men stuck aboard the Kulluk.

The rescuers had thought it would be a relatively easy job. The Coast Guard air base on Kodiak Island, the northernmost such facility in the country, is an outpost at the edge of a wilderness of water and mountains. Its search-and-rescue area spans four million square miles. To have a case “so close to home plate,” as one of them put it — 45 flight minutes and roughly a hundred miles away — seemed a stroke of incredible luck. Further, the Kulluk’s size suggested stability, a straightforward rescue.

When it appeared out of the night, “the Kulluk was wicked lit up,” said Jason Bunch, the Coast Guard rescue swimmer on the first of two helicopters. “It was like a city.” The pilots illuminated the rig further with hover lights and spotlights. They wore night-vision goggles, just in case the lights weren’t enough. They had no problems seeing the rig and the crippled Aiviq and the taut line between them, but the surrounding darkness still eroded the pilots’ depth perception. With no horizon to reference, it was harder to hover, and the goggles took away their peripheral vision.

When it appeared out of the night, “the Kulluk was wicked lit up,” said Jason Bunch, the Coast Guard rescue swimmer on the first of two helicopters. “It was like a city.” The pilots illuminated the rig further with hover lights and spotlights. They wore night-vision goggles, just in case the lights weren’t enough. They had no problems seeing the rig and the crippled Aiviq and the taut line between them, but the surrounding darkness still eroded the pilots’ depth perception. With no horizon to reference, it was harder to hover, and the goggles took away their peripheral vision.

There are two primary ways Jayhawk crews save people at sea: They lower a basket to the deck of the stricken vessel and hoist them up, or they pluck them out of the water by lowering a basket and a swimmer like Bunch, a 12-year Kodiak veteran, who in 50-foot swells and 35-degree water will drag them to the basket himself.

But now that the Kulluk was being towed from its “stern,” the point of attachment for the emergency towline, it and the Aiviq were oriented exactly the wrong way for an approach. In order to maintain control, the helicopters would ideally face the heavy winds head-on, but the derrick blocked their path. If they tried to hover above the flight deck, the only obvious place for a hoist, there was a perfect tail wind, which made steering unpredictable and dangerous.

The wind blew the tops off some of the massive swells, but otherwise they weren’t breaking. The swells came in close sets, one right after another, interrupted by long sets of “monster waves” more than twice as high. The Kulluk tipped severely but somewhat rhythmically until the monsters arrived. “As the bigger and bigger ones came, they made it go around in a circle,” Bunch told me in Kodiak. His eyes went buggy. His right hand gyrated wildly. The deck, normally 70 feet above the water, “was dipping so deep that the water was surging on it.”

“You know when you have a bobber on a fishing pole,” he asked, “and then you throw it out there and reel in really fast, and it makes a wake over the bobber? That’s what it looked like.” If the Kulluk’s deck was pitching that badly, he said, you could imagine what the derrick was doing. It looked as if it were trying to bat the helicopters out of the sky.

The two helicopters took turns circling the drill rig, looking for a way in, for any place to lower the basket. They radioed back and forth with the Kulluk’s crew — “Very, very professional, very squared away,” Bunch said, “considering the environment” — and briefly wondered if there was a way to get them in the water to be picked up by the swimmers. It was impossible. The jump from the deck to the sea could kill a man if he timed it wrong. If it didn’t, the Kulluk could kill him on the next swing of the bat. They flew back to Kodiak, refueled, brainstormed some more at the base, then went back out.

Six hours had passed from the moment Bunch and his crew first flew over the Kulluk. It was still night. Bunch took out his watch and began timing the gaps between big sets of swells. “We started coming up with some harebrained schemes,” he said. They looked for “maybe doable” spots for the hoist. “We’d have 90 seconds to be in and out, which is just impossible, but we were actually talking about it.” Reality — what their commander called “the courage not to do it” — slowly set in. The two helicopters returned to base. “We were experienced,” Bunch said, “so eventually we were like, ‘This is stupid.' ”

The rescuers had thought it would be a relatively easy job. The Coast Guard air base on Kodiak Island, the northernmost such facility in the country, is an outpost at the edge of a wilderness of water and mountains. Its search-and-rescue area spans four million square miles. To have a case “so close to home plate,” as one of them put it — 45 flight minutes and roughly a hundred miles away — seemed a stroke of incredible luck. Further, the Kulluk’s size suggested stability, a straightforward rescue.

When it appeared out of the night, “the Kulluk was wicked lit up,” said Jason Bunch, the Coast Guard rescue swimmer on the first of two helicopters. “It was like a city.” The pilots illuminated the rig further with hover lights and spotlights. They wore night-vision goggles, just in case the lights weren’t enough. They had no problems seeing the rig and the crippled Aiviq and the taut line between them, but the surrounding darkness still eroded the pilots’ depth perception. With no horizon to reference, it was harder to hover, and the goggles took away their peripheral vision.

When it appeared out of the night, “the Kulluk was wicked lit up,” said Jason Bunch, the Coast Guard rescue swimmer on the first of two helicopters. “It was like a city.” The pilots illuminated the rig further with hover lights and spotlights. They wore night-vision goggles, just in case the lights weren’t enough. They had no problems seeing the rig and the crippled Aiviq and the taut line between them, but the surrounding darkness still eroded the pilots’ depth perception. With no horizon to reference, it was harder to hover, and the goggles took away their peripheral vision.There are two primary ways Jayhawk crews save people at sea: They lower a basket to the deck of the stricken vessel and hoist them up, or they pluck them out of the water by lowering a basket and a swimmer like Bunch, a 12-year Kodiak veteran, who in 50-foot swells and 35-degree water will drag them to the basket himself.

But now that the Kulluk was being towed from its “stern,” the point of attachment for the emergency towline, it and the Aiviq were oriented exactly the wrong way for an approach. In order to maintain control, the helicopters would ideally face the heavy winds head-on, but the derrick blocked their path. If they tried to hover above the flight deck, the only obvious place for a hoist, there was a perfect tail wind, which made steering unpredictable and dangerous.

The wind blew the tops off some of the massive swells, but otherwise they weren’t breaking. The swells came in close sets, one right after another, interrupted by long sets of “monster waves” more than twice as high. The Kulluk tipped severely but somewhat rhythmically until the monsters arrived. “As the bigger and bigger ones came, they made it go around in a circle,” Bunch told me in Kodiak. His eyes went buggy. His right hand gyrated wildly. The deck, normally 70 feet above the water, “was dipping so deep that the water was surging on it.”

“You know when you have a bobber on a fishing pole,” he asked, “and then you throw it out there and reel in really fast, and it makes a wake over the bobber? That’s what it looked like.” If the Kulluk’s deck was pitching that badly, he said, you could imagine what the derrick was doing. It looked as if it were trying to bat the helicopters out of the sky.

The two helicopters took turns circling the drill rig, looking for a way in, for any place to lower the basket. They radioed back and forth with the Kulluk’s crew — “Very, very professional, very squared away,” Bunch said, “considering the environment” — and briefly wondered if there was a way to get them in the water to be picked up by the swimmers. It was impossible. The jump from the deck to the sea could kill a man if he timed it wrong. If it didn’t, the Kulluk could kill him on the next swing of the bat. They flew back to Kodiak, refueled, brainstormed some more at the base, then went back out.

Six hours had passed from the moment Bunch and his crew first flew over the Kulluk. It was still night. Bunch took out his watch and began timing the gaps between big sets of swells. “We started coming up with some harebrained schemes,” he said. They looked for “maybe doable” spots for the hoist. “We’d have 90 seconds to be in and out, which is just impossible, but we were actually talking about it.” Reality — what their commander called “the courage not to do it” — slowly set in. The two helicopters returned to base. “We were experienced,” Bunch said, “so eventually we were like, ‘This is stupid.' ”

by McKenzie Funk, NY Times | Read more:

Image: James Mason,Toni Greaves/Getty ImagesBye Bae

The International House of Pancakes set itself apart among chain restaurants this September when it tweeted, “Pancakes. Errybody got time fo’ dat.” But the American starch dispensary—whose claims to internationality include a middling presence in Canada, four stores in the Middle East, and a menu disconcertingly inclusive of burritos, spaghetti, and the word French—failed to distinguish itself the next month with its tweet “Pancakes bae <3.”

At that point, the term bae had already been used by the official social-media accounts of Olive Garden, Jamba Juice, Pizza Hut, Whole Foods, Mountain Dew, AT&T, Wal-Mart, Burger King and, not surprisingly, the notoriously idiosyncratic Internet personas of Arby’s and Denny’s. Each time, the word was delivered with magnificently forceful offhandedness, the calculated ease of the doll that comes to life and tries to pass herself off as a real girl but fails to fully conceal the hinges in her knees. (“What hinges? Oh, these?”)

At that point, the term bae had already been used by the official social-media accounts of Olive Garden, Jamba Juice, Pizza Hut, Whole Foods, Mountain Dew, AT&T, Wal-Mart, Burger King and, not surprisingly, the notoriously idiosyncratic Internet personas of Arby’s and Denny’s. Each time, the word was delivered with magnificently forceful offhandedness, the calculated ease of the doll that comes to life and tries to pass herself off as a real girl but fails to fully conceal the hinges in her knees. (“What hinges? Oh, these?”)

This bae trendspotting is courtesy of a newly minted Twitter account calledBrands Saying Bae, which tweeted its first on December 27. Yesterday morning it had 7,000 followers, and by evening it had doubled to 14,000. That is the sort of audience engagement and growth that corporate accounts almost never see, despite their best attempts at hipness through dubious cultural appropriation. Brands Saying Bae is reminding people, rather, that advertising—of which social-media accounts for businesses are a part—seeks out that authenticity, twists it out of shape, and turns culture against people. Our brains are cannily adapted to sense inauthenticity and come to hate what is force-fed. So it is with a heavy heart that we mourn this year the loss of bae, inevitable as it was.

Bae was generally adored as a word in 2014, even finding itself among the runners-up for the Oxford Dictionaries’ Word of the Year. (Along with normcore and slacktivism, though all would eventually suffer a disappointing loss at the hands of the uninspired vape.) Oxford’s blog loosely defined bae as a “term of endearment for one’s romantic partner” common among teenagers, with “origins in African-American English,” perpetuated widely on social media and in music, particularly hip-hop and R&B. The lyrical database Rap Genius actually tracesbae back as far as 2005. But after nearly a decade of subcultural percolation, 2014 was the year that bae went fully mainstream. (...)

In the case of bae, Urban Dictionary entries date back years and have been very widely read. One user on the site defined it as “baby, boo, sweetie” in December of 2008, pegging its usage to Western Florida. Even before that, in August of 2006, a user defined it as “a lover or significant other”—though in the ensuing years that definition has garnered equal shares of up-votes and down-votes, with an impressive 11,000 of each. It’s impossible to parse how many of those readers disagree with the particulars of the definition, and how many are simply expressing distaste for the word.

Video blogger William Haynes, who would be among the down-votes, made an adamant case in his popular YouTube series in August that “unknown to the general populace, bae is actually an acronym.” So it would technically be BAE. And according to Haynes, it means Before Anyone Else. That theory has mild support on Urban Dictionary, though it first appeared long after the initial definitions.

Katy Steinmetz in Time aptly mentioned another, more likely origin story earlier this year—one that also accounts for the uncommon a-e pairing—that bae is simply a shortened version of babe (or baby, or beau). “Slangsters do love to embrace the dropped-letter versions of words,” she wrote, noting that in some circles cool has become coo, crazy cray, et cetera. (...)

Now the ordinary people on the Internet appropriating bae are the people who run the social-media accounts for commercial brands. That all of this might be affecting linguistic patterns in a broader way is interesting. The commercial appropriation of a word signals the end of its hipness in any case, but as Kwame Opam at The Verge called it, “appropriation of urban youth culture” can banish a term to a particularly bleached sphere of irrelevance.

The most egregious usage involves the lack of any joke, or even logic. In August, Pizza Hut tweeted “Bacon Stuffed Crust. Bae-con Stuffed Crust.” What the Brands Saying Bae twitter has highlighted is the absurdity of that gimmick, which is the same as is employed in a sitcom where an elderly woman says something sexual, and then, cue the laugh track. The humor is ostensibly to come from the juxtaposition of the source and the nature of the diction. Brands aren’t supposed to talk like that. Whaaaat? It’s the same tired device that killed OMG and basic. (IHOP also tweeted, in June, “Pancakes or you’re basic.”) Laughing. Out. Loud.

At that point, the term bae had already been used by the official social-media accounts of Olive Garden, Jamba Juice, Pizza Hut, Whole Foods, Mountain Dew, AT&T, Wal-Mart, Burger King and, not surprisingly, the notoriously idiosyncratic Internet personas of Arby’s and Denny’s. Each time, the word was delivered with magnificently forceful offhandedness, the calculated ease of the doll that comes to life and tries to pass herself off as a real girl but fails to fully conceal the hinges in her knees. (“What hinges? Oh, these?”)

At that point, the term bae had already been used by the official social-media accounts of Olive Garden, Jamba Juice, Pizza Hut, Whole Foods, Mountain Dew, AT&T, Wal-Mart, Burger King and, not surprisingly, the notoriously idiosyncratic Internet personas of Arby’s and Denny’s. Each time, the word was delivered with magnificently forceful offhandedness, the calculated ease of the doll that comes to life and tries to pass herself off as a real girl but fails to fully conceal the hinges in her knees. (“What hinges? Oh, these?”)This bae trendspotting is courtesy of a newly minted Twitter account calledBrands Saying Bae, which tweeted its first on December 27. Yesterday morning it had 7,000 followers, and by evening it had doubled to 14,000. That is the sort of audience engagement and growth that corporate accounts almost never see, despite their best attempts at hipness through dubious cultural appropriation. Brands Saying Bae is reminding people, rather, that advertising—of which social-media accounts for businesses are a part—seeks out that authenticity, twists it out of shape, and turns culture against people. Our brains are cannily adapted to sense inauthenticity and come to hate what is force-fed. So it is with a heavy heart that we mourn this year the loss of bae, inevitable as it was.

Bae was generally adored as a word in 2014, even finding itself among the runners-up for the Oxford Dictionaries’ Word of the Year. (Along with normcore and slacktivism, though all would eventually suffer a disappointing loss at the hands of the uninspired vape.) Oxford’s blog loosely defined bae as a “term of endearment for one’s romantic partner” common among teenagers, with “origins in African-American English,” perpetuated widely on social media and in music, particularly hip-hop and R&B. The lyrical database Rap Genius actually tracesbae back as far as 2005. But after nearly a decade of subcultural percolation, 2014 was the year that bae went fully mainstream. (...)

In the case of bae, Urban Dictionary entries date back years and have been very widely read. One user on the site defined it as “baby, boo, sweetie” in December of 2008, pegging its usage to Western Florida. Even before that, in August of 2006, a user defined it as “a lover or significant other”—though in the ensuing years that definition has garnered equal shares of up-votes and down-votes, with an impressive 11,000 of each. It’s impossible to parse how many of those readers disagree with the particulars of the definition, and how many are simply expressing distaste for the word.

Video blogger William Haynes, who would be among the down-votes, made an adamant case in his popular YouTube series in August that “unknown to the general populace, bae is actually an acronym.” So it would technically be BAE. And according to Haynes, it means Before Anyone Else. That theory has mild support on Urban Dictionary, though it first appeared long after the initial definitions.

Katy Steinmetz in Time aptly mentioned another, more likely origin story earlier this year—one that also accounts for the uncommon a-e pairing—that bae is simply a shortened version of babe (or baby, or beau). “Slangsters do love to embrace the dropped-letter versions of words,” she wrote, noting that in some circles cool has become coo, crazy cray, et cetera. (...)

Now the ordinary people on the Internet appropriating bae are the people who run the social-media accounts for commercial brands. That all of this might be affecting linguistic patterns in a broader way is interesting. The commercial appropriation of a word signals the end of its hipness in any case, but as Kwame Opam at The Verge called it, “appropriation of urban youth culture” can banish a term to a particularly bleached sphere of irrelevance.

The most egregious usage involves the lack of any joke, or even logic. In August, Pizza Hut tweeted “Bacon Stuffed Crust. Bae-con Stuffed Crust.” What the Brands Saying Bae twitter has highlighted is the absurdity of that gimmick, which is the same as is employed in a sitcom where an elderly woman says something sexual, and then, cue the laugh track. The humor is ostensibly to come from the juxtaposition of the source and the nature of the diction. Brands aren’t supposed to talk like that. Whaaaat? It’s the same tired device that killed OMG and basic. (IHOP also tweeted, in June, “Pancakes or you’re basic.”) Laughing. Out. Loud.

by James Hamblin, The Atlantic | Read more:

Image: Paul Michael Hughes/ShutterstockTuesday, December 30, 2014

Are Some Diets “Mass Murder”?

[T]he Inuit, the Masai, and the Samburu people of Uganda all originally ate diets that were 60-80% fat and yet were not obese and did not have hypertension or heart disease.

The hypothesis that saturated fat is the main dietary cause of cardiovascular disease is strongly associated with one man, Ancel Benjamin Keys, a biologist at the University of Minnesota. […] Keys launched his “diet-heart hypothesis” at a meeting in New York in 1952, when the United States was at the peak of its epidemic of heart disease, with his study showing a close correlation between deaths from heart disease and proportion of fat in the diet in men in six countries (Japan, Italy, England and Wales, Australia, Canada, and the United States). Keys studied few men and did not have a reliable way of measuring diets, and in the case of the Japanese and Italians he studied them soon after the second world war, when there were food shortages. Keys could have gathered data from many more countries and people (women as well as men) and used more careful methods, but, suggests Teicholz, he found what he wanted to find. […]

The hypothesis that saturated fat is the main dietary cause of cardiovascular disease is strongly associated with one man, Ancel Benjamin Keys, a biologist at the University of Minnesota. […] Keys launched his “diet-heart hypothesis” at a meeting in New York in 1952, when the United States was at the peak of its epidemic of heart disease, with his study showing a close correlation between deaths from heart disease and proportion of fat in the diet in men in six countries (Japan, Italy, England and Wales, Australia, Canada, and the United States). Keys studied few men and did not have a reliable way of measuring diets, and in the case of the Japanese and Italians he studied them soon after the second world war, when there were food shortages. Keys could have gathered data from many more countries and people (women as well as men) and used more careful methods, but, suggests Teicholz, he found what he wanted to find. […]

At a World Health Organization meeting in 1955 Keys’s hypothesis was met with great criticism, but in response he designed the highly influential Seven Countries Study, which was published in 1970 and showed a strong correlation between saturated fat (Keys had moved on from fat to saturated fat) and deaths from heart disease. Keys did not select countries (such as France, Germany, or Switzerland) where the correlation did not seem so neat, and in Crete and Corfu he studied only nine men. […]

[T]he fat hypothesis led to a massive change in the US and subsequently international diet. One congressional staffer, Nick Mottern, wrote a report recommending that fat be reduced from 40% to 30% of energy intake, saturated fat capped at 10%, and carbohydrate increased to 55-60%. These recommendations went through to Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which were published for the first time in 1980. (Interestingly, a recommendation from Mottern that sugar be reduced disappeared along the way.)

It might be expected that the powerful US meat and dairy lobbies would oppose these guidelines, and they did, but they couldn’t counter the big food manufacturers such as General Foods, Quaker Oats, Heinz, the National Biscuit Company, and the Corn Products Refining Corporation, which were both more powerful and more subtle. In 1941 they set up the Nutrition Foundation, which formed links with scientists and funded conferences and research before there was public funding for nutrition research. […]

Saturated fats such as lard, butter, and suet, which are solid at room temperature, had for centuries been used for making biscuits, pastries, and much else, but when saturated fat became unacceptable a substitute had to be found. The substitute was trans fats, and since the 1980s these fats, which are not found naturally except in some ruminants, have been widely used and are now found throughout our bodies. There were doubts about trans fats from the very beginning, but Teicholz shows how the food companies were highly effective in countering any research that raised the risks of trans fats. […]

Another consequence of the fat hypothesis is that around the world diets have come to include much more carbohydrate, including sugar and high fructose corn syrup, which is cheap, extremely sweet, and “a calorie source but not a nutrient.”2 5 25 More and more scientists believe that it is the surfeit of refined carbohydrates that is driving the global pandemic of obesity, diabetes, and non-communicable diseases.

by Richard Smith, BMJ | Read more:

The hypothesis that saturated fat is the main dietary cause of cardiovascular disease is strongly associated with one man, Ancel Benjamin Keys, a biologist at the University of Minnesota. […] Keys launched his “diet-heart hypothesis” at a meeting in New York in 1952, when the United States was at the peak of its epidemic of heart disease, with his study showing a close correlation between deaths from heart disease and proportion of fat in the diet in men in six countries (Japan, Italy, England and Wales, Australia, Canada, and the United States). Keys studied few men and did not have a reliable way of measuring diets, and in the case of the Japanese and Italians he studied them soon after the second world war, when there were food shortages. Keys could have gathered data from many more countries and people (women as well as men) and used more careful methods, but, suggests Teicholz, he found what he wanted to find. […]

The hypothesis that saturated fat is the main dietary cause of cardiovascular disease is strongly associated with one man, Ancel Benjamin Keys, a biologist at the University of Minnesota. […] Keys launched his “diet-heart hypothesis” at a meeting in New York in 1952, when the United States was at the peak of its epidemic of heart disease, with his study showing a close correlation between deaths from heart disease and proportion of fat in the diet in men in six countries (Japan, Italy, England and Wales, Australia, Canada, and the United States). Keys studied few men and did not have a reliable way of measuring diets, and in the case of the Japanese and Italians he studied them soon after the second world war, when there were food shortages. Keys could have gathered data from many more countries and people (women as well as men) and used more careful methods, but, suggests Teicholz, he found what he wanted to find. […]At a World Health Organization meeting in 1955 Keys’s hypothesis was met with great criticism, but in response he designed the highly influential Seven Countries Study, which was published in 1970 and showed a strong correlation between saturated fat (Keys had moved on from fat to saturated fat) and deaths from heart disease. Keys did not select countries (such as France, Germany, or Switzerland) where the correlation did not seem so neat, and in Crete and Corfu he studied only nine men. […]

[T]he fat hypothesis led to a massive change in the US and subsequently international diet. One congressional staffer, Nick Mottern, wrote a report recommending that fat be reduced from 40% to 30% of energy intake, saturated fat capped at 10%, and carbohydrate increased to 55-60%. These recommendations went through to Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which were published for the first time in 1980. (Interestingly, a recommendation from Mottern that sugar be reduced disappeared along the way.)

It might be expected that the powerful US meat and dairy lobbies would oppose these guidelines, and they did, but they couldn’t counter the big food manufacturers such as General Foods, Quaker Oats, Heinz, the National Biscuit Company, and the Corn Products Refining Corporation, which were both more powerful and more subtle. In 1941 they set up the Nutrition Foundation, which formed links with scientists and funded conferences and research before there was public funding for nutrition research. […]

Saturated fats such as lard, butter, and suet, which are solid at room temperature, had for centuries been used for making biscuits, pastries, and much else, but when saturated fat became unacceptable a substitute had to be found. The substitute was trans fats, and since the 1980s these fats, which are not found naturally except in some ruminants, have been widely used and are now found throughout our bodies. There were doubts about trans fats from the very beginning, but Teicholz shows how the food companies were highly effective in countering any research that raised the risks of trans fats. […]

Another consequence of the fat hypothesis is that around the world diets have come to include much more carbohydrate, including sugar and high fructose corn syrup, which is cheap, extremely sweet, and “a calorie source but not a nutrient.”2 5 25 More and more scientists believe that it is the surfeit of refined carbohydrates that is driving the global pandemic of obesity, diabetes, and non-communicable diseases.

by Richard Smith, BMJ | Read more:

Beyond Meat

I dumped meat a few weeks ago, and it was not an easy breakup. Some of my most treasured moments have involved a deck, a beer, and a cheeseburger. But the more I learned, the more I understood that the relationship wasn’t good for either of us. A few things you should never do if you want to eat factory meat in unconflicted bliss: write a story on water scarcity in the American Southwest; Google “How much shit is in my hamburger?”; watch an undercover video of a slaughterhouse in action; and read the 2009 Worldwatch Institute report “Livestock and Climate Change.”

I did them all. And that was that. By then I knew that with every burger I consumed, I was helping to suck America’s rivers dry, munching on a fecal casserole seasoned liberally with E. coli, passively condoning an orgy of torture that would make Hannibal Lecter blanch, and accelerating global warming as surely as if I’d plowed my Hummer into a solar installation. We all needed to kick the meat habit, starting with me.

I did them all. And that was that. By then I knew that with every burger I consumed, I was helping to suck America’s rivers dry, munching on a fecal casserole seasoned liberally with E. coli, passively condoning an orgy of torture that would make Hannibal Lecter blanch, and accelerating global warming as surely as if I’d plowed my Hummer into a solar installation. We all needed to kick the meat habit, starting with me.

Yet previous attempts had collapsed in the face of time-sucking whole-food preparation and cardboard-scented tofu products. All the veggie burgers I knew of seemed to come in two flavors of unappealing: the brown-rice, high-carb, nap-inducing mush bomb, and the colon-wrecking gluten chew puck. Soylent? In your pasty dreams. If I couldn’t have meat, I needed something damn close. A high-performance, low-commitment protein recharge, good with Budweiser.

I took long, moody walks on the dirt roads near my Vermont house. I passed my neighbor’s farm. One of his beef cattle stepped up to the fence and gazed at me. My eyes traced his well-marbled flanks and meaty chest. I stared into those bottomless brown eyes. “I can’t quit you,” I whispered to him.

But I did. Not because my willpower suddenly rose beyond its default Lebowski setting, but because a box arrived at my door and made it easy.

Inside were four quarter-pound brown patties. I tossed one on the grill. It hit with a satisfying sizzle. Gobbets of lovely fat began to bubble out. A beefy smell filled the air. I browned a bun. Popped a pilsner. Mustard, ketchup, pickle, onions. I threw it all together with some chips on the side and took a bite. I chewed. I thought. I chewed some more. And then I began to get excited about the future.

It was called the Beast Burger, and it came from a Southern California company called Beyond Meat, located a few blocks from the ocean. At that point, the Beast was still a secret, known only by its code name: the Manhattan Beach Project. I’d had to beg Ethan Brown, the company’s 43-year-old CEO, to send me a sample.

And it was vegan. “More protein than beef,” Brown told me when I rang him up after tasting it. “More omegas than salmon. More calcium than milk. More antioxidants than blueberries. Plus muscle-recovery aids. It’s the ultimate performance burger.”

“How do you make it so meat-like?” I asked.

“It is meat,” he replied enigmatically. “Come on out. We’ll show you our steer.”

Byond Meat HQ was a brick warehouse located a stone’s throw from Chevron’s massive El Segundo refinery, which hiccuped gray fumes into the clear California sky. “Old economy, new economy,” Brown said as we stepped inside. Two-dozen wholesome millennials tapped away at laptops on temporary tables in the open space, which looked remarkably like a set that had been thrown together that morning for a movie about startups. Bikes and surfboards leaned in the corners. In the test kitchen, the Beyond Meat chef, Dave Anderson—former celebrity chef to the stars and cofounder of vegan-mayo company Hampton Creek—was frying experimental burgers made of beans, quinoa, and cryptic green things.

The “steer” was the only one with its own space. It glinted, steely and unfeeling, in the corner of the lab. It was a twin-screw extruder, the food-industry workhorse that churns out all the pastas and PowerBars of the world. Beyond Meat’s main extruders, as well as its 60 other employees, labor quietly in Missouri, producing the company’s current generation of meat substitutes, but this was the R&D steer. To make a Beast Burger, powdered pea protein, water, sunflower oil, and various nutrients and natural flavors go into a mixer at one end, are cooked and pressurized, get extruded out the back, and are then shaped into patties ready to be reheated on consumers’ grills.

“It’s about the dimensions of a large steer, right?” Brown said to me as we admired it. “And it does the same thing.” By which he meant that plant stuff goes in one end, gets pulled apart, and is then reassembled into fibrous bundles of protein. A steer does this to build muscle. The extruder in the Beyond Meat lab does it to make meat. Not meat-like substances, Brown will tell you. Meat. Meat from plants. Because what is meat but a tasty, toothy hunk of protein? Do we really need animals to assemble it for us, or have we reached a stage of enlightenment where we can build machines to do the dirty work for us?

Livestock, in fact, are horribly inefficient at making meat. Only about 3 percent of the plant matter that goes into a steer winds up as muscle. The rest gets burned for energy, ejected as methane, blown off as excess heat, shot out the back of the beast, or repurposed into non-meat-like things such as blood, bone, and brains. The process buries river systems in manure and requires an absurd amount of land. Roughly three-fifths of all farmland is used to grow beef, although it accounts for just 5 percent of our protein. But we love meat, and with the developing world lining up at the table and sharpening their steak knives, global protein consumption is expected to double by 2050.

I did them all. And that was that. By then I knew that with every burger I consumed, I was helping to suck America’s rivers dry, munching on a fecal casserole seasoned liberally with E. coli, passively condoning an orgy of torture that would make Hannibal Lecter blanch, and accelerating global warming as surely as if I’d plowed my Hummer into a solar installation. We all needed to kick the meat habit, starting with me.

I did them all. And that was that. By then I knew that with every burger I consumed, I was helping to suck America’s rivers dry, munching on a fecal casserole seasoned liberally with E. coli, passively condoning an orgy of torture that would make Hannibal Lecter blanch, and accelerating global warming as surely as if I’d plowed my Hummer into a solar installation. We all needed to kick the meat habit, starting with me.Yet previous attempts had collapsed in the face of time-sucking whole-food preparation and cardboard-scented tofu products. All the veggie burgers I knew of seemed to come in two flavors of unappealing: the brown-rice, high-carb, nap-inducing mush bomb, and the colon-wrecking gluten chew puck. Soylent? In your pasty dreams. If I couldn’t have meat, I needed something damn close. A high-performance, low-commitment protein recharge, good with Budweiser.

I took long, moody walks on the dirt roads near my Vermont house. I passed my neighbor’s farm. One of his beef cattle stepped up to the fence and gazed at me. My eyes traced his well-marbled flanks and meaty chest. I stared into those bottomless brown eyes. “I can’t quit you,” I whispered to him.

But I did. Not because my willpower suddenly rose beyond its default Lebowski setting, but because a box arrived at my door and made it easy.

Inside were four quarter-pound brown patties. I tossed one on the grill. It hit with a satisfying sizzle. Gobbets of lovely fat began to bubble out. A beefy smell filled the air. I browned a bun. Popped a pilsner. Mustard, ketchup, pickle, onions. I threw it all together with some chips on the side and took a bite. I chewed. I thought. I chewed some more. And then I began to get excited about the future.

It was called the Beast Burger, and it came from a Southern California company called Beyond Meat, located a few blocks from the ocean. At that point, the Beast was still a secret, known only by its code name: the Manhattan Beach Project. I’d had to beg Ethan Brown, the company’s 43-year-old CEO, to send me a sample.

And it was vegan. “More protein than beef,” Brown told me when I rang him up after tasting it. “More omegas than salmon. More calcium than milk. More antioxidants than blueberries. Plus muscle-recovery aids. It’s the ultimate performance burger.”

“How do you make it so meat-like?” I asked.

“It is meat,” he replied enigmatically. “Come on out. We’ll show you our steer.”

Byond Meat HQ was a brick warehouse located a stone’s throw from Chevron’s massive El Segundo refinery, which hiccuped gray fumes into the clear California sky. “Old economy, new economy,” Brown said as we stepped inside. Two-dozen wholesome millennials tapped away at laptops on temporary tables in the open space, which looked remarkably like a set that had been thrown together that morning for a movie about startups. Bikes and surfboards leaned in the corners. In the test kitchen, the Beyond Meat chef, Dave Anderson—former celebrity chef to the stars and cofounder of vegan-mayo company Hampton Creek—was frying experimental burgers made of beans, quinoa, and cryptic green things.

The “steer” was the only one with its own space. It glinted, steely and unfeeling, in the corner of the lab. It was a twin-screw extruder, the food-industry workhorse that churns out all the pastas and PowerBars of the world. Beyond Meat’s main extruders, as well as its 60 other employees, labor quietly in Missouri, producing the company’s current generation of meat substitutes, but this was the R&D steer. To make a Beast Burger, powdered pea protein, water, sunflower oil, and various nutrients and natural flavors go into a mixer at one end, are cooked and pressurized, get extruded out the back, and are then shaped into patties ready to be reheated on consumers’ grills.