As 2017 begins, Canada may be the last immigrant nation left standing. Our government believes in the value of immigration, as does the majority of the population. We took in an estimated 300,000 newcomers in 2016, including 48,000 refugees, and we want them to become citizens; around 85% of permanent residents eventually do. Recently there have been concerns about bringing in single Arab men, but otherwise Canada welcomes people from all faiths and corners. The greater Toronto area is now the most diverse city on the planet, with half its residents born outside the country; Vancouver, Calgary, Ottawa and Montreal aren’t far behind. Annual immigration accounts for roughly 1% of the country’s current population of 36 million.

Canada has been over-praised lately for, in effect, going about our business as usual. In 2016 such luminaries as US President Barack Obama and Bono, no less, declared “the world needs more Canada”. In October, the Economist blared “Liberty Moves North: Canada’s Example to the World” on its cover, illustrated by the Statue of Liberty haloed in a maple leaf and wielding a hockey stick. Infamously, on the night of the US election Canada’s official immigration website crashed, apparently due to the volume of traffic.

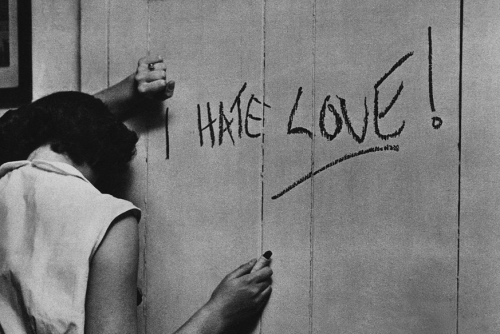

Of course, 2016 was also the year – really the second running – when many western countries turned angrily against immigration, blaming it for a variety of ills in what journalist Doug Saunders calls the “global reflex appeal to fear”. Alongside the rise of nativism has emerged a new nationalism that can scarcely be bothered to deny its roots in racial identities and exclusionary narratives.

Of course, 2016 was also the year – really the second running – when many western countries turned angrily against immigration, blaming it for a variety of ills in what journalist Doug Saunders calls the “global reflex appeal to fear”. Alongside the rise of nativism has emerged a new nationalism that can scarcely be bothered to deny its roots in racial identities and exclusionary narratives.

Compared to such hard stances, Canada’s almost cheerful commitment to inclusion might at first appear almost naive. It isn’t. There are practical reasons for keeping the doors open. Starting in the 1990s, low fertility and an aging population began slowing Canada’s natural growth rate. Ten years ago, two-thirds of population increase was courtesy of immigration. By 2030, it is projected to be 100%.

The economic benefits are also self-evident, especially if full citizenship is the agreed goal. All that “settlers” – ie, Canadians who are not indigenous to the land – need do is look in the mirror to recognize the generally happy ending of an immigrant saga. Our government repeats it, our statistics confirm it, our own eyes and ears register it: diversity fuels, not undermines, prosperity.

But as well as practical considerations for remaining an immigrant country, Canadians, by and large, are also philosophically predisposed to an openness that others find bewildering, even reckless. The prime minister, Justin Trudeau, articulated this when he told the New York Times Magazine that Canada could be the “first postnational state”. He added: “There is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada.”

The remark, made in October 2015, failed to cause a ripple – but when I mentioned it to Michael Bach, Germany’s minister for European affairs, who was touring Canada to learn more about integration, he was astounded. No European politician could say such a thing, he said. The thought was too radical.

For a European, of course, the nation-state model remains sacrosanct, never mind how ill-suited it may be to an era of dissolving borders and widespread exodus. The modern state – loosely defined by a more or less coherent racial and religious group, ruled by internal laws and guarded by a national army – took shape in Europe. Telling an Italian or French citizen they lack a “core identity” may not be the best vote-winning strategy.

To Canadians, in contrast, the remark was unexceptional. After all, one of the country’s greatest authors, Mavis Gallant, once defined a Canadian as “someone with a logical reason to think he may be one” – not exactly a ringing assertion of a national character type. Trudeau could, in fact, have been voicing a chronic anxiety among Canadians: the absence of a shared identity.

But he wasn’t. He was outlining, however obliquely, a governing principle about Canada in the 21st century. We don’t talk about ourselves in this manner often, and don’t yet have the vocabulary to make our case well enough. Even so, the principle feels right. Odd as it may seem, Canada may finally be owning our postnationalism.

There’s more than one story in all this. First and foremost, postnationalism is a frame to understand our ongoing experiment in filling a vast yet unified geographic space with the diversity of the world. It is also a half-century old intellectual project, born of the country’s awakening from colonial slumber. But postnationalism has also been in intermittent practise for centuries, since long before the nation-state of Canada was formalised in 1867. In some sense, we have always been thinking differently about this continent-wide landmass, using ideas borrowed from Indigenous societies. From the moment Europeans began arriving in North America they were made welcome by the locals, taught how to survive and thrive amid multiple identities and allegiances.

That welcome was often betrayed, in particular during the late 19th and 20th centuries, when settler Canada did profound harm to Indigenous people. But, if the imbalance remains, so too does the influence: the model of another way of belonging.

Can any nation truly behave “postnationally” – ie without falling back on the established mechanisms of state governance and control? The simple answer is no.

Canada has borders, where guards check passports, and an army. It asserts the occasional modest territorial claim. Trudeau is more aware than most of these mechanisms: he oversees them.

It can also be argued that Canada enjoys the luxury of thinking outside the nation-state box courtesy of its behemoth neighbour to the south. The state needn’t defend its borders too forcefully or make that army too large, and Canada’s economic prosperity may be as straightforward as continuing to do 75% of its trade with the US. Being liberated, the thinking goes, from the economic and military stresses that most other countries face gives Canada the breathing room, and the confidence, to experiment with more radical approaches to society. Lucky us.

Nor is there uniform agreement within Canada about being it post-anything. When the novelist Yann Martel casually described his homeland as “the greatest hotel on earth,” he meant it as a compliment – but some read it as an endorsement of newcomers deciding to view Canada as a convenient waystation: a security, business or real-estate opportunity, with no lasting responsibilities attached.

Likewise, plenty of Canadians believe we possess a set of normative values, and want newcomers to prove they abide by them. Kellie Leitch, who is running for the leadership of the Conservative party, suggested last autumn that we screen potential immigrants for “anti-Canadian values.” A minister in the previous Conservative government, Chris Alexander, pledged in 2015 to set up a tip-line for citizens to report “barbaric cultural practises”. And in the last election, the outgoing prime minster, Stephen Harper, tried in vain to hamstring Trudeau’s popularity by confecting a debate about the hijab.

To add to the mix, the French-speaking province of Quebec already constitutes one distinctive nation, as do the 50-plus First Nations spread across the country. All have their own perspectives and priorities, and may or may not be interested in a postnational frame. (That said, Trudeau is a bilingual Montrealer, and Quebec a vibrantly diverse society.)

In short, the nation-state of Canada, while wrapped in less bunting than other global versions, is still recognisable. But postnational thought is less about hand-holding in circles and shredding passports. It’s about the use of a different lens to examine the challenges and precepts of an entire politics, economy and society.

Canada has been over-praised lately for, in effect, going about our business as usual. In 2016 such luminaries as US President Barack Obama and Bono, no less, declared “the world needs more Canada”. In October, the Economist blared “Liberty Moves North: Canada’s Example to the World” on its cover, illustrated by the Statue of Liberty haloed in a maple leaf and wielding a hockey stick. Infamously, on the night of the US election Canada’s official immigration website crashed, apparently due to the volume of traffic.

Of course, 2016 was also the year – really the second running – when many western countries turned angrily against immigration, blaming it for a variety of ills in what journalist Doug Saunders calls the “global reflex appeal to fear”. Alongside the rise of nativism has emerged a new nationalism that can scarcely be bothered to deny its roots in racial identities and exclusionary narratives.

Of course, 2016 was also the year – really the second running – when many western countries turned angrily against immigration, blaming it for a variety of ills in what journalist Doug Saunders calls the “global reflex appeal to fear”. Alongside the rise of nativism has emerged a new nationalism that can scarcely be bothered to deny its roots in racial identities and exclusionary narratives.Compared to such hard stances, Canada’s almost cheerful commitment to inclusion might at first appear almost naive. It isn’t. There are practical reasons for keeping the doors open. Starting in the 1990s, low fertility and an aging population began slowing Canada’s natural growth rate. Ten years ago, two-thirds of population increase was courtesy of immigration. By 2030, it is projected to be 100%.

The economic benefits are also self-evident, especially if full citizenship is the agreed goal. All that “settlers” – ie, Canadians who are not indigenous to the land – need do is look in the mirror to recognize the generally happy ending of an immigrant saga. Our government repeats it, our statistics confirm it, our own eyes and ears register it: diversity fuels, not undermines, prosperity.

But as well as practical considerations for remaining an immigrant country, Canadians, by and large, are also philosophically predisposed to an openness that others find bewildering, even reckless. The prime minister, Justin Trudeau, articulated this when he told the New York Times Magazine that Canada could be the “first postnational state”. He added: “There is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada.”

The remark, made in October 2015, failed to cause a ripple – but when I mentioned it to Michael Bach, Germany’s minister for European affairs, who was touring Canada to learn more about integration, he was astounded. No European politician could say such a thing, he said. The thought was too radical.

For a European, of course, the nation-state model remains sacrosanct, never mind how ill-suited it may be to an era of dissolving borders and widespread exodus. The modern state – loosely defined by a more or less coherent racial and religious group, ruled by internal laws and guarded by a national army – took shape in Europe. Telling an Italian or French citizen they lack a “core identity” may not be the best vote-winning strategy.

To Canadians, in contrast, the remark was unexceptional. After all, one of the country’s greatest authors, Mavis Gallant, once defined a Canadian as “someone with a logical reason to think he may be one” – not exactly a ringing assertion of a national character type. Trudeau could, in fact, have been voicing a chronic anxiety among Canadians: the absence of a shared identity.

But he wasn’t. He was outlining, however obliquely, a governing principle about Canada in the 21st century. We don’t talk about ourselves in this manner often, and don’t yet have the vocabulary to make our case well enough. Even so, the principle feels right. Odd as it may seem, Canada may finally be owning our postnationalism.

There’s more than one story in all this. First and foremost, postnationalism is a frame to understand our ongoing experiment in filling a vast yet unified geographic space with the diversity of the world. It is also a half-century old intellectual project, born of the country’s awakening from colonial slumber. But postnationalism has also been in intermittent practise for centuries, since long before the nation-state of Canada was formalised in 1867. In some sense, we have always been thinking differently about this continent-wide landmass, using ideas borrowed from Indigenous societies. From the moment Europeans began arriving in North America they were made welcome by the locals, taught how to survive and thrive amid multiple identities and allegiances.

That welcome was often betrayed, in particular during the late 19th and 20th centuries, when settler Canada did profound harm to Indigenous people. But, if the imbalance remains, so too does the influence: the model of another way of belonging.

Can any nation truly behave “postnationally” – ie without falling back on the established mechanisms of state governance and control? The simple answer is no.

Canada has borders, where guards check passports, and an army. It asserts the occasional modest territorial claim. Trudeau is more aware than most of these mechanisms: he oversees them.

It can also be argued that Canada enjoys the luxury of thinking outside the nation-state box courtesy of its behemoth neighbour to the south. The state needn’t defend its borders too forcefully or make that army too large, and Canada’s economic prosperity may be as straightforward as continuing to do 75% of its trade with the US. Being liberated, the thinking goes, from the economic and military stresses that most other countries face gives Canada the breathing room, and the confidence, to experiment with more radical approaches to society. Lucky us.

Nor is there uniform agreement within Canada about being it post-anything. When the novelist Yann Martel casually described his homeland as “the greatest hotel on earth,” he meant it as a compliment – but some read it as an endorsement of newcomers deciding to view Canada as a convenient waystation: a security, business or real-estate opportunity, with no lasting responsibilities attached.

Likewise, plenty of Canadians believe we possess a set of normative values, and want newcomers to prove they abide by them. Kellie Leitch, who is running for the leadership of the Conservative party, suggested last autumn that we screen potential immigrants for “anti-Canadian values.” A minister in the previous Conservative government, Chris Alexander, pledged in 2015 to set up a tip-line for citizens to report “barbaric cultural practises”. And in the last election, the outgoing prime minster, Stephen Harper, tried in vain to hamstring Trudeau’s popularity by confecting a debate about the hijab.

To add to the mix, the French-speaking province of Quebec already constitutes one distinctive nation, as do the 50-plus First Nations spread across the country. All have their own perspectives and priorities, and may or may not be interested in a postnational frame. (That said, Trudeau is a bilingual Montrealer, and Quebec a vibrantly diverse society.)

In short, the nation-state of Canada, while wrapped in less bunting than other global versions, is still recognisable. But postnational thought is less about hand-holding in circles and shredding passports. It’s about the use of a different lens to examine the challenges and precepts of an entire politics, economy and society.

by Charles Foran, The Guardian | Read more:

Image: Jacqui Oakley