Wednesday, November 13, 2019

I Relented on My Toy Gun Ban. Here's What I Learned.

Toy guns were never part of my parenting plan. In fact, for a long time, I had a no-guns-at-home policy that was total and unwavering, extending even to the Nerf and water varieties. The ban was instituted for ideological and safety reasons; it bears repeating that we have a crisis of gun violence in America. According to the Pew Research Center, almost 40,000 people in the U.S. died of gun-related violence (homicide, suicide, or accidental shooting) in 2017. Three in 10 American adults own at least one gun; many own more. I am not one of them, and I loathe for my kids to grow up believing that anything made to kill another living being is cool, or fun, or normal.

But to my great surprise, I've recently come around on the issue of toy guns. I wouldn't recommend gifting them at a baby shower, or a second birthday, nor would I supply them automatically to any child. But, if I were to relive my kids' earlier years, my emphatic no would perhaps become a maybe. After all, toys — even toy weapons — are about make-believe, and my kids seem to understand that better than I did.

Many children, regardless of their backgrounds or parental proclivities, delight in toy guns and other gun-like things. I've heard stories of households without toy guns where little ones fashion them out of clay or sticks or toast. Maybe this is because, at one point or another, even the most sheltered of kids will meet other kids with toy guns. Maybe kids are drawn to guns because in our society — and in mainstream media especially — guns are a symbol of power. Or maybe it's just that, in my son's own words, shooting stuff is fun.

Many children, regardless of their backgrounds or parental proclivities, delight in toy guns and other gun-like things. I've heard stories of households without toy guns where little ones fashion them out of clay or sticks or toast. Maybe this is because, at one point or another, even the most sheltered of kids will meet other kids with toy guns. Maybe kids are drawn to guns because in our society — and in mainstream media especially — guns are a symbol of power. Or maybe it's just that, in my son's own words, shooting stuff is fun.

But for upwards of nine years, my ban never wavered. When my daughter and son, now seven and nearly 10, were tiny, shielding them from toy guns was simple. I kept them away from mainstream media and informed any potential gift-givers of the no-gun policy. Then, once my kids were old enough to realize they were missing out on a certain ilk of plaything, they pined after shooting implements. How they begged for the forbidden. But if anything remotely gun-like breached my defenses, I was sure to weed it out. My protections may have been, in retrospect, a tad extreme, but — in service to their innocence — I regret nothing.

Then, everything changed, as my family prepared for a long-distance move. Toy-by-toy, my kids were required to cull their stash. They sensed my weakness in the moment, and ruthlessly exploited it the way kids do. "Mom," they asked, "in our new house can we have just one Nerf gun?"

Distracted and overwhelmed by the towers of boxes and the even taller to-do list — I relented, hoping they'd soon forget my lapse. But once we were settled again, they remembered. One Nerf weapon turned into two. Two Nerfs required the purchase of more Nerf "darts." And belts. And camo. And eye protection. And another Nerf weapon each. Plus water guns.

I tried to comfort myself. They're brightly-colored, I thought. I have not exchanged hard-earned cash for AR-15 lookalikes.

Nevertheless, the once-banned toys crept insidiously, inexorably into our lives, our cupboards, my dreams. The first time a neighbor kid showed up at our house with an arsenal, I nearly slammed the door in the 6-year-old's face. But, swallowing my aversion, I stepped aside, both physically and symbolically, to yield my own kids the privilege of self-determination.

Meanwhile, my inner hippie mom (who, long before parenthood, earned a Master's in conflict resolution) screamed, How did this happen to us?! And my mind raced: What if toy guns draw my kids' interest to shooting-style video games? What if violent media encourages the use of real guns to solve problems? Would they streak through the yard like miniaturized warriors, aiming guns at faces or hearts, shouting, "Bang! You're dead!"?

by Danielle Simone Brand, The Week | Read more:

But to my great surprise, I've recently come around on the issue of toy guns. I wouldn't recommend gifting them at a baby shower, or a second birthday, nor would I supply them automatically to any child. But, if I were to relive my kids' earlier years, my emphatic no would perhaps become a maybe. After all, toys — even toy weapons — are about make-believe, and my kids seem to understand that better than I did.

Many children, regardless of their backgrounds or parental proclivities, delight in toy guns and other gun-like things. I've heard stories of households without toy guns where little ones fashion them out of clay or sticks or toast. Maybe this is because, at one point or another, even the most sheltered of kids will meet other kids with toy guns. Maybe kids are drawn to guns because in our society — and in mainstream media especially — guns are a symbol of power. Or maybe it's just that, in my son's own words, shooting stuff is fun.

Many children, regardless of their backgrounds or parental proclivities, delight in toy guns and other gun-like things. I've heard stories of households without toy guns where little ones fashion them out of clay or sticks or toast. Maybe this is because, at one point or another, even the most sheltered of kids will meet other kids with toy guns. Maybe kids are drawn to guns because in our society — and in mainstream media especially — guns are a symbol of power. Or maybe it's just that, in my son's own words, shooting stuff is fun.But for upwards of nine years, my ban never wavered. When my daughter and son, now seven and nearly 10, were tiny, shielding them from toy guns was simple. I kept them away from mainstream media and informed any potential gift-givers of the no-gun policy. Then, once my kids were old enough to realize they were missing out on a certain ilk of plaything, they pined after shooting implements. How they begged for the forbidden. But if anything remotely gun-like breached my defenses, I was sure to weed it out. My protections may have been, in retrospect, a tad extreme, but — in service to their innocence — I regret nothing.

Then, everything changed, as my family prepared for a long-distance move. Toy-by-toy, my kids were required to cull their stash. They sensed my weakness in the moment, and ruthlessly exploited it the way kids do. "Mom," they asked, "in our new house can we have just one Nerf gun?"

Distracted and overwhelmed by the towers of boxes and the even taller to-do list — I relented, hoping they'd soon forget my lapse. But once we were settled again, they remembered. One Nerf weapon turned into two. Two Nerfs required the purchase of more Nerf "darts." And belts. And camo. And eye protection. And another Nerf weapon each. Plus water guns.

I tried to comfort myself. They're brightly-colored, I thought. I have not exchanged hard-earned cash for AR-15 lookalikes.

Nevertheless, the once-banned toys crept insidiously, inexorably into our lives, our cupboards, my dreams. The first time a neighbor kid showed up at our house with an arsenal, I nearly slammed the door in the 6-year-old's face. But, swallowing my aversion, I stepped aside, both physically and symbolically, to yield my own kids the privilege of self-determination.

Meanwhile, my inner hippie mom (who, long before parenthood, earned a Master's in conflict resolution) screamed, How did this happen to us?! And my mind raced: What if toy guns draw my kids' interest to shooting-style video games? What if violent media encourages the use of real guns to solve problems? Would they streak through the yard like miniaturized warriors, aiming guns at faces or hearts, shouting, "Bang! You're dead!"?

by Danielle Simone Brand, The Week | Read more:

Image: Three Lions/Getty Images, Aerial3/iStock

How "The Memory Police" Makes You See

Earlier this year, Pantheon Books published Yoko Ogawa’s masterly novel “The Memory Police,” in an English translation by Stephen Snyder. (It was published in Japanese in 1994.) It’s a dreamlike story of dystopia, set on an unnamed island that’s being engulfed by an epidemic of forgetting. In the novel, the psychological toll of this forgetting is rendered in physical reality: when objects disappear from memory, they disappear from real life.

These disappearances are enforced by the Memory Police, a fascist squad that sweeps through the island, ransacking houses to confiscate lingering evidence of what’s been forgotten. Otherwise, Ogawa’s forgetting process is fittingly inexact. Things tend to disappear overnight; in the morning, the islanders—“eyes closed, ears pricked, trying to sense the flow of the morning air”—sense that something has changed. They try to acknowledge these disappearances, gathering in the street and talking about what they are losing. Sometimes the natural world complies, as if in a fairy tale: as roses disappear, a blanket of multicolored petals appears in the river. When birds disappear, people open their birdcages and release their confused pets up to the sky. Less poetic objects—stamps, green beans—vanish, too. Ships and maps are gone, so no one can leave or really understand where they are. A period of hazy limbo surrounds each disappearance. There are components to forgetting: the thing disappears, and then the memory of that thing disappears, and then the memory of forgetting that thing disappears, too.

These disappearances are enforced by the Memory Police, a fascist squad that sweeps through the island, ransacking houses to confiscate lingering evidence of what’s been forgotten. Otherwise, Ogawa’s forgetting process is fittingly inexact. Things tend to disappear overnight; in the morning, the islanders—“eyes closed, ears pricked, trying to sense the flow of the morning air”—sense that something has changed. They try to acknowledge these disappearances, gathering in the street and talking about what they are losing. Sometimes the natural world complies, as if in a fairy tale: as roses disappear, a blanket of multicolored petals appears in the river. When birds disappear, people open their birdcages and release their confused pets up to the sky. Less poetic objects—stamps, green beans—vanish, too. Ships and maps are gone, so no one can leave or really understand where they are. A period of hazy limbo surrounds each disappearance. There are components to forgetting: the thing disappears, and then the memory of that thing disappears, and then the memory of forgetting that thing disappears, too.The narrator, who, like the island, is unnamed, is a novelist. Her mother, a sculptor, was murdered by the Memory Police, who regularly round up and disappear the few islanders who still have working memories, and her late father was an ornithologist. (He dies five years before birds disappear and is spared the sight of his life’s work being carted away in garbage bags.) The narrator has published three novels, all of which revolve around disappearance: a piano tuner whose lover has gone missing, a ballerina who lost a leg, a boy whose chromosomes are being destroyed by a disease. Throughout “The Memory Police,” she works on a novel-in-progress about a typist whose voice is vanishing. She’s processing reality through a metaphorical device, re-creating the mechanism of the book that she herself is embedded in.

The narrator spends much of her time with an old man, a former ferryman who lives on a boat that now registers to them only as an unusable object. “I mean, things are disappearing more quickly than they are being created, right?” she asks him. She goes on, “It’s subtle but it seems to be speeding up, and we have to watch out. If it goes on like this and we can’t compensate for the things that get lost, the island will soon be nothing but absences and holes, and when it’s completely hollowed out, we’ll all disappear without a trace.” The old man says yes—when he was a child, the island seemed fuller. “But as things got thinner, more full of holes, our hearts got thinner, too, diluted somehow,” he says. Ogawa expresses this attrition in the novel’s unembellished language and the eerie calm that pervades it—as the novel progresses, you feel as if a white fog is slowly thickening. On the island, possibilities are becoming foreclosed both literally and spiritually. When the residents forget birds and roses, they forget what these things conjure inside them: flight, freedom, extravagance, desire.

Allegories of collective degeneration have a tendency toward the phantasmagoric, as in José Saramago’s novel “Blindness,” which was published in 1997. In that novel, all the people in an unnamed city lose their physical sight, and the place swiftly descends into hellish depths of degradation and despair. But one of the most affecting aspects of “The Memory Police” is the lack of misery in the narrative. At first, this feels comforting, moving—an assurance that life is worth living even in the most reduced circumstances. The narrator adopts a dog that’s left behind after a kidnapping; she spends days gathering small treasures to throw a birthday party for the old man. The two of them take care of each other, and they protect the man who edits the narrator’s novels: he still has his memories, so they help him to hide from the Memory Police in a secret compartment in the narrator’s house.

But then it begins to seem possible that despair itself has been forgotten—that the islanders can’t agonize over the end that’s coming because the idea of endings has also disappeared. The narrator asks her editor if he thinks that the islanders’ hearts are decaying. “I don’t know whether that’s the right word, but I do know that you’re changing, and not in a way that can be easily reversed or undone. It seems to be leading to an end that frightens me a great deal,” he says.

I thought, then, about non-magical disappearances. We are often unable to conceptualize the true magnitude of certain inevitable losses. Even when regularly confronted with the most concrete and urgent sort of reality—that we have less than a year and a half before the planet’s climate is irreversibly headed toward catastrophe, for example—we tend, like the people in Ogawa’s novel, to forget. “End . . . conclusion . . . limit—how many times had I tried to imagine where I was headed, using words like these?” the narrator wonders. “But I’d never managed to get very far. It was impossible to consider the problem for very long, before my senses froze and I felt myself suffocating.” She finds herself, in conversation, “feeling that I was leaving out the most important thing—whatever that was.”

by Jia Tolentino, New Yorker | Read more:

Image: Yann Kebbi

What's Blockchain Actually Good for, Anyway?

Image: Ariel Davis

[ed. See also: Blockchain is Dead? Crypto Geeks Debate Merits of Once Dear Tech (Bloomberg).]

[ed. See also: Blockchain is Dead? Crypto Geeks Debate Merits of Once Dear Tech (Bloomberg).]

Real ID is Really Coming

Four of the country’s largest airlines have begun to accept reservations to fly on or after Oct. 1, 2020, but those carriers offer little, if any, warning on their booking sites about the new security documents that will be required to board a plane after that date.

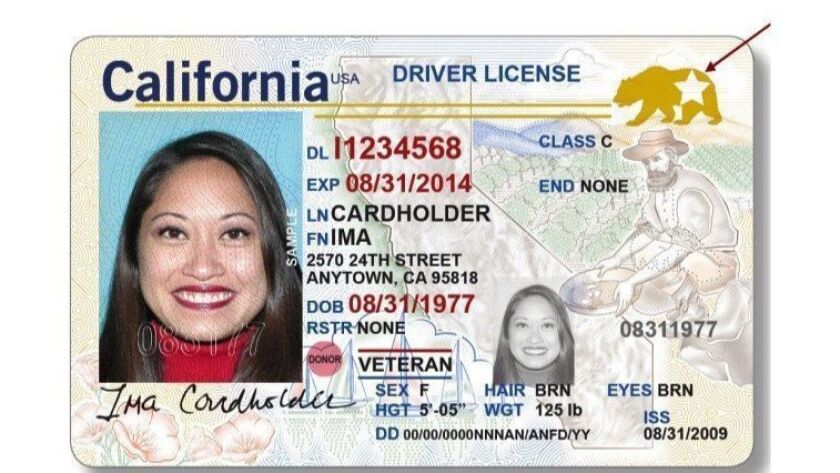

Under federal law, a traditional state-issued drivers license or identification card won’t be accepted to board a plane. Starting Oct. 1, passengers can only fly with an enhanced identification card or drivers license — known as a Real ID — or a federally approved form of identification such as a passport or military ID.

Travel industry experts estimates that 99 million Americans currently don’t have a Real ID, passport or another valid ID, according to a survey commissioned by the U.S. Travel Assn. That means nearly 40% of American adults won’t be able to board an airline to visit family for the holidays next year. (...)

Congress passed the Real ID act in 2005, based on the recommendations of the 9/11 Commission, to set a nationwide standard for state-issued identification cards and driver’s licenses. But the deadline to impose the changes on all 50 states has been postponed several times over the last few years.

Congress passed the Real ID act in 2005, based on the recommendations of the 9/11 Commission, to set a nationwide standard for state-issued identification cards and driver’s licenses. But the deadline to impose the changes on all 50 states has been postponed several times over the last few years.Forty-seven of the nation’s 50 states are now issuing the enhanced identification cards and drivers licenses that comply with the new standards. The Real ID cards and license are identified with a gold or black star in the top right corner. Oregon and Oklahoma have been given extensions to comply with the law and New Jersey’s ID is under review.

The Department of Homeland Security issued a request Nov. 8 to private firms that do business with the federal government for technologies that could streamline the process for applying for a Real ID card or license. The move opens the way for development of faster application online and the potential of carrying the enhanced identification on phones.

In California, residents need to produce several forms of identification to obtain a Real ID card, including utility bills, a birth certificate, a social security card or tax forms. The state will continue to issue traditional driver’s licenses or ID cards that can be renewed by mail but those can’t be used to board a commercial plane starting Oct.1. (...)

The Transportation Security Administration, which for months has been posting signs about the requirement at airports across the country, doesn’t plan to delay the implementation of the new requirements again, TSA spokeswoman Lorie Dankers said.

“The TSA does not encourage people to wait,” she said. “Waiting is not a good strategy.”

The worst-case scenario, said Barnes of the travel trade group, is that Americans ignore the requirements until next fall when more than 80,000 Americans who don’t have the proper identification documents show up at airports across the country to travel for the Thanksgiving holiday only to be turned away.

“The TSA does not encourage people to wait,” she said. “Waiting is not a good strategy.”

The worst-case scenario, said Barnes of the travel trade group, is that Americans ignore the requirements until next fall when more than 80,000 Americans who don’t have the proper identification documents show up at airports across the country to travel for the Thanksgiving holiday only to be turned away.

by Hugo Martin, LA Times | Read more:

Image: DMV

[ed. Good luck getting one. It took me three tries at DMV to get the specific documentation they'd accept (you do know where your original social security card, birth certificate, et al. are stored, right?]

Tuesday, November 12, 2019

Tech Duopoly Killed the Headphone Jack

The reviews are in and they are almost universal: Apple's new AirPods Pro are great. And why wouldn't they be? Despite many flaws in the original AirPods — poor fit and mediocre sound quality, to name a couple — they quickly became the most popular headphones in the world. All Apple had to do was make some obvious changes and apply their considerable engineering talent and, presto, they have another hit.

It's not just engineering quality and design that has millions of people ready to pony up a full $250 for the new earbuds, though. Rather, despite not being quite as good as some competing models from Sony or even Amazon, the AirPods are like all Apple products: they work best with other Apple products — pairing quickly, activating Siri, and so on. It's convenient — and perhaps all a little bit too neat. Apple removed the headphone jack from their phones, ostensibly to make thinner devices, and then released expensive wireless buds that yet again take advantage of the walled garden of Apple. Now the iPhone 11 phones are out, thicker than last year's model, and the AirPods Pro are the perfect match for your $1,000 phone.

The problem? When Apple and Google control the two major computing systems, things that work best with those systems tend to be the ones that succeed. So first, companies kill the headphone jack — and soon, perhaps, they will also start to kill competition.

The problem? When Apple and Google control the two major computing systems, things that work best with those systems tend to be the ones that succeed. So first, companies kill the headphone jack — and soon, perhaps, they will also start to kill competition.This isn't merely theoretical. Google famously flopped in the smartwatch market, in large part because, unlike Apple, it had no in-house department to design chips, and instead had to rely on partner Qualcomm, who haven't been able to compete with Apple for years. That's the corporate case for vertical integration: when you control all the parts, you can make better stuff.

Now, looking to make up for its past mistakes, Google has bought FitBit, the maker of wearable fitness trackers and smartwatches. Just as antitrust chatter starts to ramp up amid worries of tech's increasing consolidation of power, one of the world's largest companies swallows an ostensible competitor not only to absorb talent to make its own smartwatches, but also to hoover up its data.

The smartwatch example is illuminating. More than any other tech, smartwatches currently rely on the smartphone they are paired with for much of their functionality. An Apple Watch only works if you have an iPhone — and speaking as an Apple Watch owner, it's a powerful form of lock-in. In one sense, it's about tech companies pairing products with each other because they'll work more effectively together. But it also shows how the vertically integrated system encourages both users and companies to form little silos of tech which end up discouraging interoperability, and with it, competition.

So we're left with a situation in which a Google thing might work better with a Google thing, but if you want to buy a phone from one company, headphones from another, and a smartwatch from another, they're never going to work quite as well as if they're all from the same company. That's not a monopoly exactly, but it is a subtle or passive form of coercion.

Making matters more complicated is the way in which services and digital assistants get baked into operating systems. Google's Assistant, for example, works best when it knows more about you — specifically, your appointments through Gmail and Google Calendar, your interest via search, and your whereabouts and travel habits through Maps. Similarly, Apple's AirPods can raise Siri hands-free but not Google's Assistant or Amazon's Alexa. It's all about tie-in, and in this case, "tie-in" means "less consumer choice."

What this means is that there isn't so much competition between individual products — between this phone or that, or these headphones or another — as much as between ecosystems: Apple's, Google's, and perhaps Amazon's and Microsoft's — though the latter two don't really have their own as much as piggyback on the other two. That isn't really competition; instead, it's a scenario in which the ecosystem owners either swallow or overshadow those who oppose them.

Image: erllre/iStock, Andrea Colarieti/iStock, DickDuerrstein/iStock

Monday, November 11, 2019

How Ambient Chill Became the New Silence

When Cooper arrived at the airport, she felt another flicker of recognition: the music playing inside the terminal sounded familiar to her, despite being pointedly inconspicuous. Then it happened again, after she boarded her flight. This time, it was the music playing in the background of the in-flight safety video. “I was like, ‘Can you just stop?’” she told me about the experience. “‘I’m going home for a holiday.’” After she landed in Australia and spent a few days sleeping off her jet lag, she went to the movies. There it was, again. “I was sitting in the theater and three ads came on in a row before the movie started,” she explains. “It was all our music.”

Cooper’s story isn’t really about transcontinental coincidence. It’s about the ubiquity and increased homogeneity of certain kinds of mood-setting songs. Background music has been big business for nearly a century, and in recent decades it’s been transformed by factors that are reshaping the music industry at large: streaming, algorithms, and social media. The demand for royalty-free music is growing, in large part because of the explosion of YouTube and Instagram, where influencers—especially in the beauty and travel realms—display an enormous appetite for sonic content, but often lack the pocket money to pay royalties on popular songs. YouTube claims that 500 hours of content are uploaded to the platform every minute. “Almost all of that needs music,” Cooper says; demand is “off the hook.”

Cooper’s story isn’t really about transcontinental coincidence. It’s about the ubiquity and increased homogeneity of certain kinds of mood-setting songs. Background music has been big business for nearly a century, and in recent decades it’s been transformed by factors that are reshaping the music industry at large: streaming, algorithms, and social media. The demand for royalty-free music is growing, in large part because of the explosion of YouTube and Instagram, where influencers—especially in the beauty and travel realms—display an enormous appetite for sonic content, but often lack the pocket money to pay royalties on popular songs. YouTube claims that 500 hours of content are uploaded to the platform every minute. “Almost all of that needs music,” Cooper says; demand is “off the hook.” Background music comes in a variety of flavors: piped-in playlists curated by sound designers for hotels or fast food restaurants; custom-made background music for big-budget commercials; algorithmic Spotify playlists with chill, lo-fi beats; and stock music, which permeates our environment often imperceptibly, in airports, Instagram Stories, furniture showrooms, grocery stores, banks, and hospital lobbies.

There’s almost no question that our lives are increasingly filled with sound. Noise pollution in urban spaces is also on the rise, as Kate Wagner noted in a 2018 article from The Atlantic. Wagner’s piece, “How Restaurants Got So Loud,” explains how some restaurants are louder than freeways or alarm clocks, at 70 decibels, making it almost impossible to hear a dinner companion, since trendy building materials such as slate and wood don’t absorb much sound. (Wagner measured “80 decibels in a dimly lit wine bar at dinnertime; 86 decibels at a high-end food court during brunch; 90 decibels at a brewpub in a rehabbed fire station during Friday happy hour.”)

Adding ambient music to these spaces is about setting and controlling a nearly invisible emotional forcefield for consumers; ambient music for shopping spaces, these days, is meant to soothe you or pump you up, and generally nudge your habits toward consumption. The specific calculus about mood varies by business type. A 1982 study conducted in supermarkets revealed that slow-tempo music was shown to slow customers, and they purchased more as a result. On the opposite end of the spectrum, loud pounding music may be effective for bars; one 2008 study showed that men ordered an average of one more drink in louder bars than in quieter ones, and finished their drinks more quickly.

Background music is also increasingly used to create a branded “experience,” one that’s meant to connect a customer and a brand in an intimate way, relying less on the type of song (country, rap, folk) than on its mood (sexy, aggressive, uplifting). The less complicated the mood, the better. “A good song has a single emotion in it,” Cooper tells me. “The average length of a song is two minutes and 30 seconds, which is not a lot of time. If it tries to be really happy, and then really sad, it’s confusing.” Happy stock music sells better than PremiumBeat’s sad libraries, she explains, perhaps in part because people are spurred toward purchases by happy tunes. But, Cooper says, the point of a library like PremiumBeat is that clients can find a song in a library for any emotional occasion: “I just approved a track called ‘Eulogy,’ and I was like, ‘Well, there’s only one use for that.’” (...)

Mood Media remains the global corporate giant of playlist curation; the company curates music for everyone from KFC to Gucci to Chase Bank. Mood boasts more than 500,000 clients worldwide and reaches about 150 million ears daily. The company also dabbles in other facets of the branded “experience,” including signage, audiovisual systems, and even custom smells.

“Collectively we’ve all learned that the way brick and mortar retail survives and thrives is by creating elevating experiences, without question,” says Danny Turner, global senior vice president of Mood Media. “Music is such an emotional and strong bond of connectivity with brands.” It doesn’t matter, maybe, if you buy something on-site; if the music leaves you with a positive feeling, a clear sense of a brand’s “personality,” it has done the trick.

Today, Mood Media doesn’t produce much original content; it serves to market a massive existing library of songs, some of which are popular, while others are totally unknown. Unlike the Muzak of yesteryear, a lot of Mood’s music has lyrics, though Turner says that a certain type of ambience is back in fashion. “We are seeing an overall very large swing toward a sort of ambient, chill, down-tempo, sort of like house kind of sound,” Turner says. “I’ve joked that ambient chill is the new Muzak.”

Today, the emotional manipulation of ambient music is growing increasingly specific. And we, the listeners, have become more mood-oriented too—mostly thanks to Spotify. In 2015, the company helped to engineer the shift from listening by artist or album or genre to listening by mood, building data on users’ emotional states through playlists like “Chill” or “Happy Hits,” and selling that data to advertisers and marketing firms. Spotify now claims that, “unlike generations past, millennials aren’t loyal to any specific music genre.”

Musicians who write for stock libraries need to keep up with the trends. Liam Clarke, who’s been making music for stock libraries since 2013, has a few Instagram accounts that he uses to follow bloggers, influencers, and brands of all stripes in order to keep his finger on the pulse of what people are listening to. After a more dancey, upbeat phase that lasted for a few years, Clarke says, the popular ethos today tends to be chill lo-fi, but with a beat.

Clarke got into making stock music the way many musicians do: messing around on the computer. He’d always written and played music, starting in school orchestras, but when he got the Apple program GarageBand, released in 2004, which allows people to write their own music, he could begin quickly writing music in any genre or style. Clarke also writes songs for other musicians and plays his own music. “I don’t think that’s all too different from producing for a library,” he says.

Because they have their personal brands, many artists, including Clarke, use pseudonyms in stock music libraries; his is Liam Aidan. (“You could have a song that’s the most licensed song in the world and no one would know who you are,” he says.) Once musicians upload a song to a library, it can be hard to track where it goes; they receive checks when a song is licensed and may get sent audio clips by friends or family who recognize their tunes, but, often, their work fades into the digital ether. This sometimes leads to the surprising flicker of recognition that comes from hearing one’s song out in the world, like Kate Cooper’s uncanny trip through the airport. (One stock musician found out weeks after the event that his song had been played on the red carpet at the Met Gala; another got a check for $1,800 because his song had been broadcast in Romania.)

by Sophie Haigney, Topic | Read more:

Image: Jovanna Tosello

The Seahawks-49ers Rivalry Is Back, and the NFL Is Better Off for It

When I started covering the NFL in 2011, the last version of the Seahawks-49ers rivalry was still in its infancy. The Niners went to the NFC championship game that season, but lost to the Giants in a wild contest that was swung by Kyle Williams’s botched punt return. Seattle hadn’t quite reached the same heights, finishing just 7-9 that year, but the bones of the dominant Legion of Boom teams were already in place. Marshawn Lynch had rushed for more than 1,200 yards in his first full season with the franchise, and young building blocks like Earl Thomas, Kam Chancellor, Richard Sherman, Doug Baldwin, and K.J. Wright were starting to make an impact. The embers of a rivalry may have been there, but things really ignited in 2012.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/65650641/NinersSeahawksRivalry_Getty_Ringer.0.jpg) That’s the year Seattle drafted Russell Wilson and the Niners transitioned from Alex Smith to Colin Kaepernick at quarterback. Over the next two seasons, those teams would lock horns in some of the most memorable and heated NFL games of this decade. And as they emerged as the best teams in football, Seattle and San Francisco redefined nearly every aspect of the modern NFL: from roster-building, to schematic approach, to how teams used their QBs.

That’s the year Seattle drafted Russell Wilson and the Niners transitioned from Alex Smith to Colin Kaepernick at quarterback. Over the next two seasons, those teams would lock horns in some of the most memorable and heated NFL games of this decade. And as they emerged as the best teams in football, Seattle and San Francisco redefined nearly every aspect of the modern NFL: from roster-building, to schematic approach, to how teams used their QBs.As the Steelers-Ravens rivalry hit a relative low point in the early 2010s, with Pittsburgh slowly transitioning to the early years of its high-scoring Three-Bs era, the Seahawks and Niners filled the void. Their feud burned fast and bright, flaming out after an 8-8 finish in 2014 led the Niners to fire Jim Harbaugh. But after lying dormant for several years, it seems like both teams are finally ready to rekindle the flame. On Monday night, the 8-0 49ers host the 7-2 Seahawks in one of the biggest games of the season. The stakes between these teams are sky-high once again—and the NFL is better off for it.

It’s hard to believe that the most recent version of this rivalry lasted only a couple of years, because it gave us a decade’s worth of memorable moments. Plenty of those came when both teams shared the field, but each built their own mystique against other opponents, too. I was at Candlestick Park in January 2013 when Kaepernick racked up nearly 450 total yards and four touchdowns in a divisional-round win over the Packers. It was the most physically dominant performance I’d ever seen from a quarterback to that point—the Packers defense didn’t look like it belonged on the same field as Kaepernick.

With Kaepernick at the helm, the Niners built a reputation as a dynamic power-running squad with a hulking offensive line that could grind defenses into oblivion. And with Patrick Willis, Justin Smith, and NaVorro Bowman on the other side of the ball, San Francisco had a terrifying defense to match. Harbaugh was there to provide the comic relief with some of the most memorable sideline temper tantrums ever, and together they produced some incredibly thrilling performances. (We don’t talk about the 2012 divisional-round win over the Saints nearly enough.)

At the same time, the Seahawks emerged as the loudest (in more ways than one), coolest group in football. It had been years since an NFL team had cultivated as many personalities as the Seahawks did at the start of this decade. Sherman had no qualms about chirping in Tom Brady’s face after a win. Chancellor made a habit of erasing anyone who crossed his path. Lynch trucked countless helpless defenders on his way to becoming an icon. (...)

The aspect of that game that stuck out most, though, more than any individual play, was the sense that you were watching two teams that were playing a different sport than the rest of the NFL. The pure physicality and speed on display was unlike anything else in the league during that time. And in ways both big and small, the Seahawks and Niners became the teams of the era.

by Robert Mays, The Ringer | Read more:

Image: Getty Images/Ringer illustration

[ed. Tonight. See also (from the links above): Bigger, Faster, Stronger, Louder: How the Seahawks Became the Coolest Team in the NFL (Grantland).]

Sunday, November 10, 2019

Saturday, November 9, 2019

Ted Gioia on Music as Cultural Cloud Storage

To Ted Gioia, music is a form of cloud storage for preserving human culture. And the real cultural conflict, he insists, is not between “high brow” and “low brow” music, but between the innovative and the formulaic. (...)

He joined Tyler to discuss the history and industry of music, including the reasons AI will never create the perfect songs, the strange relationship between outbreaks of disease and innovation, how the shift from record companies to Silicon Valley transformed incentive structures within the industry– and why that’s cause for concern, the vocal polyphony of Pygmy music, Bob Dylan’s Nobel prize, why input is underrated, his advice to aspiring music writers, the unsung female innovators of music history, how the Blues anticipated the sexual revolution, what Rene Girard’s mimetic theory can tell us about noisy restaurants, the reason he calls Sinatra the “Derrida of pop singing,” how to cultivate an excellent music taste, and why he loves Side B of Abbey Road. (via)

Here is the audio and transcript, the chat centered around music, including Ted’s new and fascinating book Music: A Subversive History. We talk about music and tech, the Beatles, which songs and performers we are embarrassed to like, whether jazz still can be cool, Ted’s family background, why restaurants are noisier, why the blues are disappearing, Elton John, which countries are underrated for their musics, whether anyone loves the opera, whether musical innovation is still possible, and much much more. Here are some excerpts:

Here is the audio and transcript, the chat centered around music, including Ted’s new and fascinating book Music: A Subversive History. We talk about music and tech, the Beatles, which songs and performers we are embarrassed to like, whether jazz still can be cool, Ted’s family background, why restaurants are noisier, why the blues are disappearing, Elton John, which countries are underrated for their musics, whether anyone loves the opera, whether musical innovation is still possible, and much much more. Here are some excerpts:

He joined Tyler to discuss the history and industry of music, including the reasons AI will never create the perfect songs, the strange relationship between outbreaks of disease and innovation, how the shift from record companies to Silicon Valley transformed incentive structures within the industry– and why that’s cause for concern, the vocal polyphony of Pygmy music, Bob Dylan’s Nobel prize, why input is underrated, his advice to aspiring music writers, the unsung female innovators of music history, how the Blues anticipated the sexual revolution, what Rene Girard’s mimetic theory can tell us about noisy restaurants, the reason he calls Sinatra the “Derrida of pop singing,” how to cultivate an excellent music taste, and why he loves Side B of Abbey Road. (via)

Here is the audio and transcript, the chat centered around music, including Ted’s new and fascinating book Music: A Subversive History. We talk about music and tech, the Beatles, which songs and performers we are embarrassed to like, whether jazz still can be cool, Ted’s family background, why restaurants are noisier, why the blues are disappearing, Elton John, which countries are underrated for their musics, whether anyone loves the opera, whether musical innovation is still possible, and much much more. Here are some excerpts:

Here is the audio and transcript, the chat centered around music, including Ted’s new and fascinating book Music: A Subversive History. We talk about music and tech, the Beatles, which songs and performers we are embarrassed to like, whether jazz still can be cool, Ted’s family background, why restaurants are noisier, why the blues are disappearing, Elton John, which countries are underrated for their musics, whether anyone loves the opera, whether musical innovation is still possible, and much much more. Here are some excerpts:GIOIA: …Spotify still isn’t profitable. I believe Spotify will become profitable, but they’re going to do it by putting the squeeze on people. Musicians will suffer even more, probably, in the future than they have in the past. What’s good for Spotify is not good for the whole music ecosystem.

Let me make one more point here. I think it’s very important. If you go back a few years ago, there was a value chain in music — started with the musician, worked for the record label. The records went to the record distributor. They went to the retailer, who sold the record to the consumer. At that point, everybody in that chain had a vested interest in a healthy music ecosystem in which people enjoyed songs. The more people enjoyed songs, the better business was for everybody.

That chain has been broken now. Apple would give away songs for free to sell devices. They don’t care about the viability of the music subeconomy. For them, it could be a loss leader. Google doesn’t care about music. They would give music away for free to sell ads. In fact, they do that on YouTube.

The fundamental change here is, you now have a distribution system for music in which some of the players do not have a vested interest in the broader musical experience and ecosystem. This is tremendously dangerous, and that’s the real reason why I fear the growth of streaming, is because the people involved in streaming don’t like music.And:

COWEN: Do you think music today is helping the sexual revolution or hurting it? Speaking of Prince…

GIOIA: It’s very interesting. There’s market research and focus groups about how people use music in their day-to-day life. Take, for example, this: you’re going to bring a date back to your apartment for a romantic dinner. So what do you worry about?

Well, the first thing I have to worry about is, my place is a mess. I’ve got to clean it up. That’s number one. The second thing you worry about is, what food am I going to fix? But number three on people’s list — when you interview them — is the music because they understand the music is going to seal the deal. If there’s going to be something really romantic, that music is essential.

People will agonize for hours over which music to play. I think that we miss this. People view music as distance from people’s everyday life. But in fact, people put music to work every day, and one of the premier ways they do it is in romance.

COWEN: Let’s say you were not married, and you’re 27 years old, and you’re having a date over. What music do you put on in 2019 under those conditions?

GIOIA: It’s got to always be Sinatra.

COWEN: Because that is sexier? It’s generally appealing? It’s not going to offend anyone? Why?

GIOIA: I must say up front, I am no expert on seduction, so you’re now getting me out of my main level of expertise. But I would think that if you were a seducer, you would want something that was romantic on the surface but very sexualized right below that, and no one was better at these multilayered interpretations of lyrics than Frank Sinatra.

I always call them the Derrida of pop singing because there was always the surface level and various levels that you could deconstruct. And if you are planning for that romantic date, hey, go for Frank.There is much more at the link, interesting throughout, and again here is Ted’s new book.

by Tyler Cowen, Marginal Revolution | Read more:

Labels:

Business,

Critical Thought,

Culture,

Media,

Music,

Technology

Timeout: Estonia Has a New Way to Stop Speeding Motorists

The aim of the experiment is to see how drivers perceive speeding, and whether lost time may be a stronger deterrent than lost money. The project is a collaboration between Estonia’s Home Office and the police force, and is part of a programme designed to encourage innovation in public services. Government teams propose a problem they would like to solve—such as traffic accidents caused by irresponsible driving—and work under the guidance of an “innovation unit”. Teams are expected to do all fieldwork and interviews themselves.

The aim of the experiment is to see how drivers perceive speeding, and whether lost time may be a stronger deterrent than lost money. The project is a collaboration between Estonia’s Home Office and the police force, and is part of a programme designed to encourage innovation in public services. Government teams propose a problem they would like to solve—such as traffic accidents caused by irresponsible driving—and work under the guidance of an “innovation unit”. Teams are expected to do all fieldwork and interviews themselves.“At first it was kind of a joke,” says Laura Aaben, an innovation adviser for the interior ministry, referring to the idea of timeouts. “But we kept coming back to it.” Elari Kasemets, Ms Aaben’s counterpart in the police, explained that, in interviews, drivers frequently said that having to spend time dealing with the police and being given a speeding ticket was more annoying than the cost of the ticket itself. “People pay the fines, like bills, and forget about it,” he said. (In Estonia, speeding fines generated by automatic cameras are not kept on record and have no cumulative effect, meaning that drivers don’t have their licences revoked if they get too many.)

Making drivers wait requires manpower. The team acknowledges that the experiment is not currently scalable, but hopes that technology could make it so in the future. Public reaction, though, was not what they expected. “It’s been very positive, surprisingly,” says Helelyn Tammsaar, who manages projects for the innovation unit.

by The Economist | Read more:

Image: uncredited

[ed. Pretty smart. I imagine the the babysitting problem could be overcome with temporary geotags or something. See also: Japanese commuters try new ways to deter gropers (The Economist).]

You Are What You (Don’t) Eat

In the summer of 2016, James and Becca Reed, a lower-income couple living in Austin, Texas, decided it was time to save their lives. The Reeds, married more than twenty-five years, had become morbidly obese, diabetic, and depressed. They were taking a combined thirty-two medications. Only in their early fifties, they had arrived at this condition via a well-trod path: They ate their way into it. They did no more than consume what the American food industry not only offers in abundance—salt, starch, and sweetness—but also encourages us to eat.

As nearly 40 percent of the adult US population can attest, it doesn’t take a lot of time, effort, or expense for the consequences of the American way of eating to add up. A steady diet of processed and fast food, oversized restaurant meals, and “favorited” takeout options can quickly make the average American a victim of the growing obesity epidemic. Considering that the Reeds live paycheck to paycheck, and given what we know about the strong link between economic disadvantage and poor eating choices, I was especially intrigued when a friend, who knew James and Becca from church, told me about this really interesting couple getting ready to reclaim their health in a dramatic way.

With disarming generosity, the Reeds opened their lives to me as they undertook their mission. For three months I followed and documented their progress, meeting with them several times a week, usually at the small gym they attended (on the gym owner’s dime) to talk as they exercised. What they did was both miraculous and subversive. The miraculous part is in the numbers. Becca’s blood sugar level dropped from an alarming 200 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) to a very normal 80 mg/dL; James’s cholesterol went from well over a borderline 200 mg/dL to a safe 153; both were losing 15 to 20 pounds a month. They reversed their diabetes—Becca’s score on the glycated hemoglobin test (6.5 or higher indicates the presence of diabetes) plummeted from 9.75 to 5.8—and stopped taking most of their medications. With remarkable efficiency, the Reeds did as planned. They saved their lives.

With disarming generosity, the Reeds opened their lives to me as they undertook their mission. For three months I followed and documented their progress, meeting with them several times a week, usually at the small gym they attended (on the gym owner’s dime) to talk as they exercised. What they did was both miraculous and subversive. The miraculous part is in the numbers. Becca’s blood sugar level dropped from an alarming 200 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) to a very normal 80 mg/dL; James’s cholesterol went from well over a borderline 200 mg/dL to a safe 153; both were losing 15 to 20 pounds a month. They reversed their diabetes—Becca’s score on the glycated hemoglobin test (6.5 or higher indicates the presence of diabetes) plummeted from 9.75 to 5.8—and stopped taking most of their medications. With remarkable efficiency, the Reeds did as planned. They saved their lives.

But as physically conspicuous as their transformation was (soon their clothes were hanging off their bodies), the ultimate driving force behind the Reeds’ success was subversive: They escaped a food system that had been eroding their health. On the surface, the Reeds did what healthy Americans habitually do—they walked more, went to the neighborhood pool after work, cut back on screen time, and hit the gym a few times a week. But these measures, at least when it came to emotionally sustaining their journey, struck them as too anodyne, too lacking in the sort of meaning they wanted to experience through their efforts. As they often remarked, it would have been easy to cheat on their routines unless there had been a moral dimension to their crusade. Healthful activities might have been central to their transformation, but they did not provide what the Reeds needed most: a community bound by a set of stipulations that mattered—in effect, a creed.

So when it came to confronting the food system in which the Reeds had long been entrapped, they decided it was not enough to behave like most relatively healthy Americans. Instead, they needed to adopt an entirely new identity and wrap their reinvented selves in its defining cloak. The Reeds did so by going vegan.

Food Fills the Spiritual Void

In Food Cults: How Fads, Dogma, and Doctrine Influence Diet, Kima Cargill, a psychology professor at the University of Washington, Tacoma, writes that “membership in food cults serves the same psychological functions of cult membership of any kind.” People are attracted to cohesive groups as a means of defining identity, or as Cargill puts it, “delineating in-group and out-group membership.”

As a physical matter, the Reeds did not regain their health because there is something inherently beneficial about being vegan—there’s not. It’s possible, indeed easy, to be an unhealthy vegan. Rather, the Reeds’ transition resulted, predictably, from adopting certain perfectly unremarkable practices: more exercise, portion control, and the consumption of real food, mostly vegetables, rather than processed junk. But what the vegan diet did for the Reeds was exactly what Cargill suggests it does. It allowed them to frame otherwise dull choices in an exclusive and essentialist—and often very exciting—ideology, one that gave them a sense of conviction and community. In this respect, veganism, like many rigorous diet schemes, functions like a cult, with an ethic rooted in what members won’t eat and the value imbued in that denial.

The ghost of religion hovers like a mist over America’s sprawling dietary landscape. Catholics’ abstinence from meat on Fridays, Jews’ avoidance of the flesh of cloven-hooved beasts, and the Hindus’ vegetarianism are well-known, identity-forming convergences of diet, faith, and community. But Cargill takes this religious association further, suggesting that the secularization of modern culture “has left many searching for the structure and identity that religion once provided.” Given this spiritual void, she explains, “food cults arguably replace what religion once did by prescribing organized food rules and rituals.” These are rules and rituals that—whether the diet is vegan or vegetarian, paleo or primal, Mediterranean or South Beach—nurture identities that keep us loyal, insularly focused, and passionate about what we will and, even more significantly, will not eat.

As in any religious quest, the themes of reform and conversion overlap. From Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle to Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma, a century of literature has demonized verboten foods in the interest of improving personal health and, more importantly, the quality of the nation’s food supply. Whether the offending choice is industrial meat, all meat, farmed fish, processed food, food that grandma didn’t eat, or fast food, the message is one that has been internalized as a mainstream cultural critique: Our food system is in shambles and it must, as a moral imperative, be reformed. Today, it’s no surprise that a relatively new social movement—the “Food Movement”—has emerged around these impassioned exhortations and prohibitions, fueled by congregations of the faithful urging us to “vote with our forks” to fix the system. The personal diet has become not only a cult; it has become a political statement.

Vegans, slow foodies, sustainable foodies, pescatarians, vegetarians, paleos, primals, fruititarians, juicers—this ever-expanding list of dietary sects demonstrates how we can still find new ways to define ourselves in an American dietary landscape seemingly mined to the point of exhaustion. Given the pervasive corruption and seductive power of the system by which food is produced and then presented to the American consumer, as well as our sense of political impotence in the face of this system, it’s hard not to credit the decision and commitment of someone who seeks salvation in a cult-diet conversion. But for all the options to go that route and for all our feverish enthusiasm for such diet regimes, there’s a more fundamental issue we seem to be neglecting: the larger food system itself.

Big agriculture’s fundamental problems—the emphasis on factory-farmed meat and dairy, fertilizer-intensive corn and soy production, the failure to grow a diversity of nutrient-dense plants for people to eat (rather than corn and soy for animals), agricultural policies that favor large corporate farms—have become even more entrenched. Indeed, in the last half-century, industrial food has become only more aligned with the logic of industrial animal production, less diverse in nutrients and real foods, and more reliant on mechanization (and, now it seems, artificial intelligence). All this has occurred even as cult diets have flourished. The question is thus unavoidable: Could individuals voting with their forks—thereby identifying with a diet (or at least a movement)—distract from or even undermine what we really should be doing to reform our food system: reimagining it altogether?

by James McWilliams, The Hedgehog Review | Read more:

As nearly 40 percent of the adult US population can attest, it doesn’t take a lot of time, effort, or expense for the consequences of the American way of eating to add up. A steady diet of processed and fast food, oversized restaurant meals, and “favorited” takeout options can quickly make the average American a victim of the growing obesity epidemic. Considering that the Reeds live paycheck to paycheck, and given what we know about the strong link between economic disadvantage and poor eating choices, I was especially intrigued when a friend, who knew James and Becca from church, told me about this really interesting couple getting ready to reclaim their health in a dramatic way.

With disarming generosity, the Reeds opened their lives to me as they undertook their mission. For three months I followed and documented their progress, meeting with them several times a week, usually at the small gym they attended (on the gym owner’s dime) to talk as they exercised. What they did was both miraculous and subversive. The miraculous part is in the numbers. Becca’s blood sugar level dropped from an alarming 200 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) to a very normal 80 mg/dL; James’s cholesterol went from well over a borderline 200 mg/dL to a safe 153; both were losing 15 to 20 pounds a month. They reversed their diabetes—Becca’s score on the glycated hemoglobin test (6.5 or higher indicates the presence of diabetes) plummeted from 9.75 to 5.8—and stopped taking most of their medications. With remarkable efficiency, the Reeds did as planned. They saved their lives.

With disarming generosity, the Reeds opened their lives to me as they undertook their mission. For three months I followed and documented their progress, meeting with them several times a week, usually at the small gym they attended (on the gym owner’s dime) to talk as they exercised. What they did was both miraculous and subversive. The miraculous part is in the numbers. Becca’s blood sugar level dropped from an alarming 200 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) to a very normal 80 mg/dL; James’s cholesterol went from well over a borderline 200 mg/dL to a safe 153; both were losing 15 to 20 pounds a month. They reversed their diabetes—Becca’s score on the glycated hemoglobin test (6.5 or higher indicates the presence of diabetes) plummeted from 9.75 to 5.8—and stopped taking most of their medications. With remarkable efficiency, the Reeds did as planned. They saved their lives.But as physically conspicuous as their transformation was (soon their clothes were hanging off their bodies), the ultimate driving force behind the Reeds’ success was subversive: They escaped a food system that had been eroding their health. On the surface, the Reeds did what healthy Americans habitually do—they walked more, went to the neighborhood pool after work, cut back on screen time, and hit the gym a few times a week. But these measures, at least when it came to emotionally sustaining their journey, struck them as too anodyne, too lacking in the sort of meaning they wanted to experience through their efforts. As they often remarked, it would have been easy to cheat on their routines unless there had been a moral dimension to their crusade. Healthful activities might have been central to their transformation, but they did not provide what the Reeds needed most: a community bound by a set of stipulations that mattered—in effect, a creed.

So when it came to confronting the food system in which the Reeds had long been entrapped, they decided it was not enough to behave like most relatively healthy Americans. Instead, they needed to adopt an entirely new identity and wrap their reinvented selves in its defining cloak. The Reeds did so by going vegan.

Food Fills the Spiritual Void

In Food Cults: How Fads, Dogma, and Doctrine Influence Diet, Kima Cargill, a psychology professor at the University of Washington, Tacoma, writes that “membership in food cults serves the same psychological functions of cult membership of any kind.” People are attracted to cohesive groups as a means of defining identity, or as Cargill puts it, “delineating in-group and out-group membership.”

As a physical matter, the Reeds did not regain their health because there is something inherently beneficial about being vegan—there’s not. It’s possible, indeed easy, to be an unhealthy vegan. Rather, the Reeds’ transition resulted, predictably, from adopting certain perfectly unremarkable practices: more exercise, portion control, and the consumption of real food, mostly vegetables, rather than processed junk. But what the vegan diet did for the Reeds was exactly what Cargill suggests it does. It allowed them to frame otherwise dull choices in an exclusive and essentialist—and often very exciting—ideology, one that gave them a sense of conviction and community. In this respect, veganism, like many rigorous diet schemes, functions like a cult, with an ethic rooted in what members won’t eat and the value imbued in that denial.

The ghost of religion hovers like a mist over America’s sprawling dietary landscape. Catholics’ abstinence from meat on Fridays, Jews’ avoidance of the flesh of cloven-hooved beasts, and the Hindus’ vegetarianism are well-known, identity-forming convergences of diet, faith, and community. But Cargill takes this religious association further, suggesting that the secularization of modern culture “has left many searching for the structure and identity that religion once provided.” Given this spiritual void, she explains, “food cults arguably replace what religion once did by prescribing organized food rules and rituals.” These are rules and rituals that—whether the diet is vegan or vegetarian, paleo or primal, Mediterranean or South Beach—nurture identities that keep us loyal, insularly focused, and passionate about what we will and, even more significantly, will not eat.

As in any religious quest, the themes of reform and conversion overlap. From Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle to Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma, a century of literature has demonized verboten foods in the interest of improving personal health and, more importantly, the quality of the nation’s food supply. Whether the offending choice is industrial meat, all meat, farmed fish, processed food, food that grandma didn’t eat, or fast food, the message is one that has been internalized as a mainstream cultural critique: Our food system is in shambles and it must, as a moral imperative, be reformed. Today, it’s no surprise that a relatively new social movement—the “Food Movement”—has emerged around these impassioned exhortations and prohibitions, fueled by congregations of the faithful urging us to “vote with our forks” to fix the system. The personal diet has become not only a cult; it has become a political statement.

Vegans, slow foodies, sustainable foodies, pescatarians, vegetarians, paleos, primals, fruititarians, juicers—this ever-expanding list of dietary sects demonstrates how we can still find new ways to define ourselves in an American dietary landscape seemingly mined to the point of exhaustion. Given the pervasive corruption and seductive power of the system by which food is produced and then presented to the American consumer, as well as our sense of political impotence in the face of this system, it’s hard not to credit the decision and commitment of someone who seeks salvation in a cult-diet conversion. But for all the options to go that route and for all our feverish enthusiasm for such diet regimes, there’s a more fundamental issue we seem to be neglecting: the larger food system itself.

Big agriculture’s fundamental problems—the emphasis on factory-farmed meat and dairy, fertilizer-intensive corn and soy production, the failure to grow a diversity of nutrient-dense plants for people to eat (rather than corn and soy for animals), agricultural policies that favor large corporate farms—have become even more entrenched. Indeed, in the last half-century, industrial food has become only more aligned with the logic of industrial animal production, less diverse in nutrients and real foods, and more reliant on mechanization (and, now it seems, artificial intelligence). All this has occurred even as cult diets have flourished. The question is thus unavoidable: Could individuals voting with their forks—thereby identifying with a diet (or at least a movement)—distract from or even undermine what we really should be doing to reform our food system: reimagining it altogether?

by James McWilliams, The Hedgehog Review | Read more:

Image: via

On Hawaii, the Fight for Taro’s Revival

Friday, November 8, 2019

Experience: My Face Became a Meme

The photo came from a shoot I’d done a year earlier, when I was still working as an electrical engineer. A professional photographer had got in touch after seeing my holiday photographs on Facebook. He said he was seeking someone like me to be in some stock images. Everyone is a little vain inside, myself included, so I was happy that he wanted me. He invited me to a photoshoot near my home in Budapest and we took shots in different locations and settings. Over the course of two years he took hundreds of pictures of me for photo libraries.

I thought the pictures would just be used by businesses and websites, but I wasn’t expecting the memes. People overlaid text on my pictures, talking about their wives leaving them, or saying their identity had been stolen and their bank account emptied. They used my image because it looked as if I was smiling through the pain.

I thought the pictures would just be used by businesses and websites, but I wasn’t expecting the memes. People overlaid text on my pictures, talking about their wives leaving them, or saying their identity had been stolen and their bank account emptied. They used my image because it looked as if I was smiling through the pain.Once the memes were out in the world, journalists began to contact me, and wanted to come to my home to interview me. My wife hated it: she thought it interfered in our private life and didn’t like the way I was portrayed. People thought I wasn’t a real person, that I was a Photoshop creation – someone even got in contact asking for proof that I existed.

I knew that it was impossible to stop people making memes, but it still annoyed me that Facebook pages, some with hundreds of thousands of followers, were using my photograph as their profile picture, and pretending to be me. Some kind of brand had been made out of me and I would have been a fool not to make use of it. So, in 2017, I created my own Facebook fan page and updated it with videos and stories from my travels.

That started everything going. People noticed that I had taken ownership of the meme and got in contact to offer me work. I was given a role in a television commercial for a Hungarian car dealer. In one of the adverts, I travelled to Germany to buy a used car and it broke down halfway home; if I had bought the same car through their company, the brand claimed, it wouldn’t have happened. The fee for that commercial changed my wife’s mind about the meme.

by András Arató, The Guardian | Read more:

Image: Bela Doka/The Guardian

The Dictionary of Capitalism

As you encounter the world around you, you will hear many words that go undefined. It is the task of Current Affairs to explain these terms in intelligible language, so that readers may perceive the true nature of things.

- American lives /əˈmɛrɪk(ə)n lʌɪvz/ n. the units by which the human toll of a war is measured.

- body camera /ˈbɒdi ˈkam(ə)rə/ n. a magic technology capable of turning off whenever a police officer commits a crime.

- border /ˈbɔːdə/ n. an imaginary line drawn through the world, the crossing of which is met with violence on behalf of those who may live thousands of miles away from the line.

- charter school /ˈtʃɑːtəskuːl/ n. a school that insists it can provide better education than a public school because the people who run it are not accountable to anyone.

- corporation /kɔːpəˈreɪʃ(ə)n/ n. a collectivist enterprise in which all power is vested in a small number of central planning bureaucrats at the top and the individual must surrender their autonomy to serve the interests of the planning authority.

- death tax /dɛθ taks/ n. when, upon a person becoming deceased, the state declines to transfer that person’s accumulated freedom-unit score to a different, arbitrary person who did not earn those freedom-units.

- disruption /dɪsˈrʌpʃn/ n. changing an industry standard by finding ways to pay people less for their labor.

- education /ɛdjʊˈkeɪʃ(ə)n/ n. the process of being filtered for employment based on one’s pliability and deference.

- employment /ɪmˈplɔɪm(ə)nt/ n. being granted permission to continue living in exchange for an adjustable daily quantity of toil.

- entitlements /ɪnˈtʌɪt(ə)lmənts/ n. small increases in the freedom-units afforded to the elderly, sick, and those who have too few units to survive.

- eviction /ɪˈvɪkʃ(ə)n/ n. forcible removal from one’s home for failure to provide the appropriate lord with sufficient tribute.

- fighter plane /ˈfʌɪtə pleɪn/ n. a plane that fights other planes to the death.

- fiscal responsibility /ˈfɪsk(ə)l rɪˌspɒnsɪˈbɪlɪti/ n. only spending money on things that kill people.

- food stamps /fuːd stamp/ n. a system by which the poor must humiliate themselves on a six-monthly or yearly basis in order to buy a tiny amount of food they will be shamed for possessing. (Use of the stamp for lobster will result in congressional hearings.)

- fossil fuel /ˈfɒs(ə)l fjuː(ə)l/ n. a suicide pill; brings gratification of immediate pleasures but causes death to one’s self and one’s offspring.

- genocide /ˈdʒɛnəsʌɪd/ n. something white people fear will happen to them; all other uses are disputed.

- health insurance board of directors /hɛlθ ɪnˈʃʊər(ə)ns bɔːd (ə)v dʌɪˈrɛktəs/ n. death panel.

- homeless person /ˈhəʊmlɪs ˈpəːs(ə)n/ n. a person we are choosing not to house in any of the X million properties currently empty.

- journalist /ˈdʒəːn(ə)lɪst/ n. a transcriptionist used by anonymous state officials to nudge public opinion in an appropriate direction.

- landlord /ˈlan(d)lɔːd/ n. precisely what it sounds like: the feudal ruler of a plot of land, entitled to extract wealth from all inhabitants.

- limited government /ˈlɪmɪtɪd ˈɡʌv(ə)nˌm(ə)nt/ n. government that restricts its role only to taking care of rich people.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)