Tuesday, November 19, 2019

Very Glad to Know You

What they saw was Franklin Armstrong’s first appearance on the iconic comic strip “Peanuts.” Franklin would be 50 years old this year.

Franklin was “born” after a school teacher, Harriet Glickman, had written a letter to creator Charles M. Schulz after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was shot to death outside his Memphis hotel room.

Glickman, who had kids of her own and having worked with kids, was especially aware of the power of comics among the young. “And my feeling at the time was that I realized that black kids and white kids never saw themselves [depicted] together in the classroom,” she would say.

She would write, “Since the death of Martin Luther King, ‘I’ve been asking myself what I can do to help change those conditions in our society which led to the assassination and which contribute to the vast sea of misunderstanding, hate, fear and violence.'”

Glickman asked Schulz if he could consider adding a black character to his popular comic strip, which she hoped would bring the country together and show people of color that they are not excluded from American society.

She had written to others as well, but the others feared it was too soon, that it may be costly to their careers, that the syndicate would drop them if they dared do something like that.

Charles Schulz did not have to respond to her letter, he could have just completely ignored it, and everyone would have forgotten about it. But, Schulz did take the time to respond, saying he was intrigued with the idea, but wasn’t sure whether it would be right, coming from him, he didn’t want to make matters worse, he felt that it may sound condescending to people of color.

Glickman did not give up, and continued communicating with Schulz, with Schulz surprisingly responding each time. She would even have black friends write to Schulz and explain to him what it would mean to them and gave him some suggestions on how to introduce such a character without offending anyone. This conversation would continue until one day, Schulz would tell Glickman to check her newspaper on July 31, 1968.

On that date, the cartoon, as created by Schulz, shows Charlie Brown meeting a new character, named Franklin. Other than his color, Franklin was just an ordinary kid who befriends and helps Charlie Brown. Franklin also mentions that his father was “over at Vietnam.” At the end of the series, which lasted three strips, Charlie invites Franklin to spend the night one day so they can continue their friendship.

Read more: via:

Always Be My Maybe ft. Keanu Reeves

[ed. "The only stars that matter are the one's you look at when you dream..."]

The Mister Rogers No One Saw

Up at the castle, in front of the cameras, the puppets were eagerly preparing for a festival. Dwarfed beneath high rows of stage lights, in front of painted trees, they bopped happily along the pretend stone wall. But there was a buzz kill: King Friday XIII, the mighty ruler in his bright purple cape, decreed that the festival would be a bass-violin festival.

“But you’re the only one who plays the bass violin,” one of the neighbors pointed out.

“Oh, so I am,” the king replied. “Well, it looks like I’ll have a very large audience.”

Fred Rogers was on his knees behind the castle, dressed all in black, working the puppets, his posture straight as a soldier’s, lips pursed tight as he voiced the king. There were cushions strewn on the floor and blocks of foam rubber taped to the parts of the castle where he tended to bonk his head. In one swift movement he crouched, slipped off the king, slid on another puppet. He shot his arm up, returned to his knees, but this time he slouched, his face softening as he voiced the meek and bashful Daniel Striped Tiger.

And so the neighbors scrambled about trying to figure out a way to be part of the festival. Stumped, and on the sly, they began to invent bass-violin acts they might contribute. One dressed up her accordion to look like a bass violin, another practiced a dance with one, another tried to turn herself into one by wearing a big fat bass-violin suit. Another, a goat, recited a bass-violin poem in goat language. (“Mehh.”)

And so the neighbors scrambled about trying to figure out a way to be part of the festival. Stumped, and on the sly, they began to invent bass-violin acts they might contribute. One dressed up her accordion to look like a bass violin, another practiced a dance with one, another tried to turn herself into one by wearing a big fat bass-violin suit. Another, a goat, recited a bass-violin poem in goat language. (“Mehh.”)

“If you didn’t know what was going on,” one of the guys on the crew said, “this could be a very weird situation.”

Was this O.K.? Would the king approve?

He did. In fact, he was delighted. It turned into a most rockin’ bass-violin festival, neighbors singing and twirling with pretend and real bass violins (including a puppet holding a bass-violin puppet), around balloons with little cardboard handles taped to them to look like bass violins, to rousing bass-violin/accordion polka tunes accompanying bass-violin-inspired goat poems.

I appreciated that. I worked for a different department in the building, at WQED in Pittsburgh, down the hall. They had microwave popcorn in the cafeteria. To get to the popcorn you had to walk by Studio A, and there was usually the blue castle parked outside it for storage. If the castle wasn’t there, you knew they were taping inside, and sometimes you heard music. It was fun to go in and watch, if only to take in the live music, usually jazz, and to marvel at the bizarro factor. (...)

Fred Rogers was a curious, lanky man, six feet tall and 143 pounds (exactly, he said, every day; he liked that each digit corresponded to the number of letters in the words “I love you”) and utterly devoid of pretense. He liked to pray, to play the piano, to swim and to write, and he somehow lived in a different world than I did. A hushed world of tiny things — the meager and the marginalized. A world of simple words and deceptively simple concepts, and a slowness that allowed for silence, focus and joy. We became friends for some 20 years, and I made lifelong friends with his wife, Joanne. I remember thinking that it seemed as if Fred had access to another realm, like the way pigeons have some special magnetic compass that helps them find home.

Fred died in 2003, somewhat quickly, of stomach cancer. He was 74. It was years after his death that he would, suddenly, go from a kind of lovable PBS novelty to an icon on the magnitude of the divine. It happened so fast that it was easy to gloss over his actual message. He gets reduced to a symbol. A conveyor of virtue! The god of kindness! Something like that, according to the memes.

“Just don’t make Fred into a saint.” That has become Joanne’s refrain. She’s 91 now, still a bundle of energy, lives alone in the same roomy apartment, in the university section of Pittsburgh, that she and Fred moved into after they raised their two boys. Mention her name to anyone around town who knows her, and you’ll very likely be rewarded with a fabulous grin. She’s funny. She laughs louder and bigger than just about anyone I know, to the point where it can go into a snort, which makes her go full-on guffaw. Throughout her 50-year marriage to Fred, she wasn’t the type to hang out on the set at WQED or attend production meetings. That was Fred’s thing. He had his career, and she had hers as a concert pianist. For decades she toured the country with her college classmate, Jeannine Morrison, as a piano duo; they didn’t retire the performance until 2008.

Joanne’s refrain has been adopted by people who spent their careers working with Fred in Studio A. “If you make him out to be a saint, nobody can get there,” said Hedda Sharapan, the person who worked with Fred the longest in various creative capacities over the years. “They’ll think he’s some otherworldly creature.”

“If you make him out to be a saint, people might not know how hard he worked,” Joanne said. Disciplined, focused, a perfectionist — an artist. That was the Fred she and the cast and crew knew. “I think people think of Fred as a child-development expert,” David Newell, the actor who played Mr. “Speedy Delivery” McFeely, told me recently. “As a moral example maybe. But as an artist? I don’t think they think of that.”

That was the Fred I came to know. Creating, the creative impulse and the creative process were our common interests. He wrote or co-wrote all the scripts for the program — all 33 years of it. He wrote the melodies. He wrote the lyrics. He structured a week of programming around a single theme, many of them difficult topics, like war, divorce or death.

by Jeanne Marie Laskas, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Jim Judkis

[ed. A wonderful essay.]

“But you’re the only one who plays the bass violin,” one of the neighbors pointed out.

“Oh, so I am,” the king replied. “Well, it looks like I’ll have a very large audience.”

Fred Rogers was on his knees behind the castle, dressed all in black, working the puppets, his posture straight as a soldier’s, lips pursed tight as he voiced the king. There were cushions strewn on the floor and blocks of foam rubber taped to the parts of the castle where he tended to bonk his head. In one swift movement he crouched, slipped off the king, slid on another puppet. He shot his arm up, returned to his knees, but this time he slouched, his face softening as he voiced the meek and bashful Daniel Striped Tiger.

And so the neighbors scrambled about trying to figure out a way to be part of the festival. Stumped, and on the sly, they began to invent bass-violin acts they might contribute. One dressed up her accordion to look like a bass violin, another practiced a dance with one, another tried to turn herself into one by wearing a big fat bass-violin suit. Another, a goat, recited a bass-violin poem in goat language. (“Mehh.”)

And so the neighbors scrambled about trying to figure out a way to be part of the festival. Stumped, and on the sly, they began to invent bass-violin acts they might contribute. One dressed up her accordion to look like a bass violin, another practiced a dance with one, another tried to turn herself into one by wearing a big fat bass-violin suit. Another, a goat, recited a bass-violin poem in goat language. (“Mehh.”)“If you didn’t know what was going on,” one of the guys on the crew said, “this could be a very weird situation.”

Was this O.K.? Would the king approve?

He did. In fact, he was delighted. It turned into a most rockin’ bass-violin festival, neighbors singing and twirling with pretend and real bass violins (including a puppet holding a bass-violin puppet), around balloons with little cardboard handles taped to them to look like bass violins, to rousing bass-violin/accordion polka tunes accompanying bass-violin-inspired goat poems.

I appreciated that. I worked for a different department in the building, at WQED in Pittsburgh, down the hall. They had microwave popcorn in the cafeteria. To get to the popcorn you had to walk by Studio A, and there was usually the blue castle parked outside it for storage. If the castle wasn’t there, you knew they were taping inside, and sometimes you heard music. It was fun to go in and watch, if only to take in the live music, usually jazz, and to marvel at the bizarro factor. (...)

Fred Rogers was a curious, lanky man, six feet tall and 143 pounds (exactly, he said, every day; he liked that each digit corresponded to the number of letters in the words “I love you”) and utterly devoid of pretense. He liked to pray, to play the piano, to swim and to write, and he somehow lived in a different world than I did. A hushed world of tiny things — the meager and the marginalized. A world of simple words and deceptively simple concepts, and a slowness that allowed for silence, focus and joy. We became friends for some 20 years, and I made lifelong friends with his wife, Joanne. I remember thinking that it seemed as if Fred had access to another realm, like the way pigeons have some special magnetic compass that helps them find home.

Fred died in 2003, somewhat quickly, of stomach cancer. He was 74. It was years after his death that he would, suddenly, go from a kind of lovable PBS novelty to an icon on the magnitude of the divine. It happened so fast that it was easy to gloss over his actual message. He gets reduced to a symbol. A conveyor of virtue! The god of kindness! Something like that, according to the memes.

“Just don’t make Fred into a saint.” That has become Joanne’s refrain. She’s 91 now, still a bundle of energy, lives alone in the same roomy apartment, in the university section of Pittsburgh, that she and Fred moved into after they raised their two boys. Mention her name to anyone around town who knows her, and you’ll very likely be rewarded with a fabulous grin. She’s funny. She laughs louder and bigger than just about anyone I know, to the point where it can go into a snort, which makes her go full-on guffaw. Throughout her 50-year marriage to Fred, she wasn’t the type to hang out on the set at WQED or attend production meetings. That was Fred’s thing. He had his career, and she had hers as a concert pianist. For decades she toured the country with her college classmate, Jeannine Morrison, as a piano duo; they didn’t retire the performance until 2008.

Joanne’s refrain has been adopted by people who spent their careers working with Fred in Studio A. “If you make him out to be a saint, nobody can get there,” said Hedda Sharapan, the person who worked with Fred the longest in various creative capacities over the years. “They’ll think he’s some otherworldly creature.”

“If you make him out to be a saint, people might not know how hard he worked,” Joanne said. Disciplined, focused, a perfectionist — an artist. That was the Fred she and the cast and crew knew. “I think people think of Fred as a child-development expert,” David Newell, the actor who played Mr. “Speedy Delivery” McFeely, told me recently. “As a moral example maybe. But as an artist? I don’t think they think of that.”

That was the Fred I came to know. Creating, the creative impulse and the creative process were our common interests. He wrote or co-wrote all the scripts for the program — all 33 years of it. He wrote the melodies. He wrote the lyrics. He structured a week of programming around a single theme, many of them difficult topics, like war, divorce or death.

by Jeanne Marie Laskas, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Jim Judkis

[ed. A wonderful essay.]

Labels:

Celebrities,

Culture,

Education,

Media,

Psychology,

Relationships

Monday, November 18, 2019

The Homeownership Obsession

While academics and journalists questioned the conventional wisdom, the dominant idea was that buying a house was a solid investment plan, a responsible decision that required commitment (30 years of mortgage payments) and a sturdy sense of hope. American culture has always been oriented toward the future rather than reckoning with the past, and homeownership, particularly in the suburbs, was no different. Yet this wasn’t always part of the American dream. The American dream was originally about “rags to riches, coming from nothing and ending up a robber baron,” says Rachel Heiman, associate professor of anthropology at the New School. It was about money. It was only during the McCarthy era that homeownership became a crucial part of the story.

“People rarely realize that the desire to be a homeowner isn’t a purely natural desire, though we tend to think about it as inherent,” Heiman says. When we think about the McCarthy hearings, we often remember the Hollywood aspect—the glamorous stars persecuted for their supposed leftist leanings. But before McCarthy gave his famous anti-communist speech in Wheeling, West Virginia, the senator had focused much of his career on opposing public housing and protecting corporate interests. Since the post-World War II period, the government had been providing housing to veterans and their families. “They did an extraordinary job of building affordable housing on a mass scale during the war,” explains Heiman. In the 1940s, McCarthy and other right-wing politicians became concerned that the housing projects had gone too far—McCarthy even called public housing “breeding ground[s] for communists.” In the late 1940s, he sided with William Levitt (and other private manufacturers) in their fight against public housing projects. Levitt was promoting his cookie-cutter housing communities, which McCarthy believed were more in line with America’s capitalist economic structure and ideals. (“No man who owns his own house and lot can be a communist. He has too much to do,” Levitt once famously said.) As the Cold War wore on, this sentiment grew, particularly among members of the Republican Party. From 1950 onward, Heiman says, “homeownership was packaged and sold.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19350120/Curbed_Cult_Spot_1.jpg) Suddenly, it became important for the U.S. government to shift its focus from providing housing for those in need to providing mortgage assistance. “The government helped people, but only white people, to get into the suburbs,” Heiman says. This was the legacy of redlining, a New Deal-era process of color-coding neighborhoods based on income, labeling some as good investments and others as “risky.” The government was more likely to help people refinance their homes or purchase homes in areas they deemed secure, which prevented generations of African Americans (who lived disproportionately in “risky,” i.e., low-income, areas) from being able to lift themselves out of poverty. Although redlining was outlawed in 1968 by the Fair Housing Act, the effects echoed through American culture for decades and continue to do so to this day. Popular culture also helped reinforce suburban segregation. Magazines and newspapers ran advertisements for Levittown and other similar housing developments, which nearly always showed white couples or children engaging in wholesome activities (one showed a young couple, man in uniform, drawing their dream house in the sand, while another showed a young white child jumping into a pool). Television advertisements were no better. The message was clear enough: The suburbs—and the American dream, by extension—weren’t for everyone.

Suddenly, it became important for the U.S. government to shift its focus from providing housing for those in need to providing mortgage assistance. “The government helped people, but only white people, to get into the suburbs,” Heiman says. This was the legacy of redlining, a New Deal-era process of color-coding neighborhoods based on income, labeling some as good investments and others as “risky.” The government was more likely to help people refinance their homes or purchase homes in areas they deemed secure, which prevented generations of African Americans (who lived disproportionately in “risky,” i.e., low-income, areas) from being able to lift themselves out of poverty. Although redlining was outlawed in 1968 by the Fair Housing Act, the effects echoed through American culture for decades and continue to do so to this day. Popular culture also helped reinforce suburban segregation. Magazines and newspapers ran advertisements for Levittown and other similar housing developments, which nearly always showed white couples or children engaging in wholesome activities (one showed a young couple, man in uniform, drawing their dream house in the sand, while another showed a young white child jumping into a pool). Television advertisements were no better. The message was clear enough: The suburbs—and the American dream, by extension—weren’t for everyone.As the old adage goes, a crucial part of purchasing real estate is recognizing the significance of “location, location, location,” and from the 1950s onward, that location was almost always the suburbs. But like the idea of homeownership in general, the concept of owning a suburban home was fed to Americans by people in power. Suburbia has always been good for industry. Big houses required big appliances and used lots of carbon, creating a “hydrocarbon middle-class family” that was buoyed by three industries: coal, steel, and automaking. “Suturing the growing metropolitan regions together were, of course, cars, which made the postwar American suburb possible,” writes Robert O. Self in his 2014 Salon article “Cataclysm in suburbia: The dark, twisted history of America’s oil-addicted middle class.” Self points to the 1956 National Interstate and Defense Highways Act, which provided 90 cents for every dime the states invested in interstate highways, “effectively making sprawl as much a creature of government as of the market.” (...)

I’ve spoken with dozens of millennials about the topic of homebuying—both as research for my work, and out of curiosity. I am a millennial who owns a house; I’m also a 32-year-old who watched my parents lose control of their finances in the market crash. For me, like many other adults my age, the idea of owning a house is both a dream and a nightmare.

I visited my first open house during a sunny Sunday in June. It was a quintessential spring day in Portland, Maine. Lilacs and rhododendrons were blooming, the grass was finally bright green, and the maple and oak leaves had fully unfurled. It was the ideal backdrop for viewing a three-bedroom brick cape on the outskirts of the city, especially since one of the home’s selling points is the back patio and garden, hedged in by boxwoods, made private by small trees and big fences.

This is where I found Brody Van Geem and Brooke Brown-Saracino, 30-something transplants from California who moved to Maine three years ago after being priced out of the West Coast. Portland, they thought, would be an affordable city with a “slower pace of life.” Brown-Saracino said she “couldn’t imagine a future” in California, “given how expensive it is.” When we spoke, Brown-Saracino was cradling their 5-week-old newborn. They already owned a condo downtown (on the “peninsula,” as we call Portland’s densest and most expensive area), but were looking to buy somewhere where they could be closer to nature and have a bit more room to grow their family.

When they bought their condo, this millennial couple wasn’t thinking about acquiring their “dream home.” They knew that was out of the question. “We thought of it as a more financially viable choice than renting,” said Brown-Saracino. “It felt like a very practical and financially driven decision.” She had to “reconcile” this mindset with her “lifetime notion” that the first house she bought would be a home. A place where she would raise children and live until she grew old. Or, at least, until the kids were old enough to leave for college. “This is the narrative that I think was fed to past generations—and is still a component of my emotional relationship to homeownership—but most of me had shifted to a much more practical, financial narrative,” she said. “I think this is probably driven by how expensive homeownership is today.”

University of Michigan professor Karyn Lacy, who studies black American upper-middle-class and “elite” millennials, has noticed a widespread shift in how people view their first real estate purchase. Baby boomers, she says, “went to high school, college, got married right after, and bought homes as a couple.” Now, millennials are doing everything later. They’re buying houses as single people rather than waiting to get married and have their first kids. The properties they purchase aren’t “homes,” explains Lacy. “They’re places to live without paying rent.”

This is something upper-class adults learn from their parents. “The kids that I study understand that this is a way to accumulate wealth without having to do much else,” says Lacy. “You buy it, you live in it, you go about your daily life, and in five years you’ll have a nice nest egg to move up from your starter house to your dream home.” Kids who grow up in lower-income families don’t necessarily have that same ideal instilled in them.

The next open house I visited was much quieter—it was also more expensive. It crossed the half-million-dollar mark, a divide that seems to separate properties that attract millennial buyers from properties that attract a primarily boomer crowd. In the two hours I spent talking with realtor Jody Ryan, I didn’t meet any prospective homeowners under the age of 50. Millennials, she says, don’t really want a house this big (2,700 square feet) or with so many expensive fixtures and fittings. “A lot of them are buying little ranches,” she said as we waited for another buyer to wander in. “They want splits and ranches or houses that are good for easy living.” (The other trend Ryan noticed was that millennials often want houses with big tubs for their pets, so they can “stick ’em in and spray them. They’ve got lots of pets.”)

by Katy Kelleher, Curbed | Read more:

Image: Kelly Abeln

Not Even Wrong

"Not even wrong" describes an argument or explanation that purports to be scientific but is based on invalid reasoning or speculative premises that can neither be proven correct nor falsified and thus cannot be discussed in a rigorous and scientific sense. For a meaningful discussion on whether a certain statement is true or false, the statement must satisfy the criterion of falsifiability, the inherent possibility for the statement to be tested and found false. In this sense, the phrase "not even wrong" is synonymous to "nonfalsifiable".

The phrase is generally attributed to theoretical physicist Wolfgang Pauli, who was known for his colorful objections to incorrect or careless thinking. Rudolf Peierls documents an instance in which "a friend showed Pauli the paper of a young physicist which he suspected was not of great value but on which he wanted Pauli's views. Pauli remarked sadly, 'It is not even wrong'." This is also often quoted as "That is not only not right; it is not even wrong", or in Pauli's native German, "Das ist nicht nur nicht richtig; es ist nicht einmal falsch!". Peierls remarks that quite a few apocryphal stories of this kind have been circulated and mentions that he listed only the ones personally vouched for by him. He also quotes another example when Pauli replied to Lev Landau, "What you said was so confused that one could not tell whether it was nonsense or not."

The phrase is often used to describe pseudoscience or bad science.

The phrase is generally attributed to theoretical physicist Wolfgang Pauli, who was known for his colorful objections to incorrect or careless thinking. Rudolf Peierls documents an instance in which "a friend showed Pauli the paper of a young physicist which he suspected was not of great value but on which he wanted Pauli's views. Pauli remarked sadly, 'It is not even wrong'." This is also often quoted as "That is not only not right; it is not even wrong", or in Pauli's native German, "Das ist nicht nur nicht richtig; es ist nicht einmal falsch!". Peierls remarks that quite a few apocryphal stories of this kind have been circulated and mentions that he listed only the ones personally vouched for by him. He also quotes another example when Pauli replied to Lev Landau, "What you said was so confused that one could not tell whether it was nonsense or not."

The phrase is often used to describe pseudoscience or bad science.

by Wikipedia | Read more:

[ed. See also: Briefing: Not even wrong (Guardian).]Getting a Handle on Self-Harm

“I had this Popsicle stick and carved it into sharp point and scratched myself,” Joan, a high school student in New York City said recently; she asked that her last name be omitted for privacy. “I’m not even sure where the idea came from. I just knew it was something people did. I remember crying a lot and thinking, Why did I just do that? I was kind of scared of myself.”

She felt relief as the swarm of distress dissolved, and she began to cut herself regularly, at first with a knife, then razor blades, cutting her wrists, forearms and eventually much of her body. “I would do it for five to 15 minutes, and afterward I didn’t have that terrible feeling. I could go on with my day.”

Self-injury, particularly among adolescent girls, has become so prevalent so quickly that scientists and therapists are struggling to catch up. About 1 in 5 adolescents report having harmed themselves to soothe emotional pain at least once, according to a review of three dozen surveys in nearly a dozen countries, including the United States, Canada and Britain. Habitual self harm, over time, is a predictor for higher suicide risk in many individuals, studies suggest.

Self-injury, particularly among adolescent girls, has become so prevalent so quickly that scientists and therapists are struggling to catch up. About 1 in 5 adolescents report having harmed themselves to soothe emotional pain at least once, according to a review of three dozen surveys in nearly a dozen countries, including the United States, Canada and Britain. Habitual self harm, over time, is a predictor for higher suicide risk in many individuals, studies suggest.But there are very few dedicated research centers for self-harm, and even fewer clinics specializing in treatment. When youngsters who injure themselves seek help, they are often met with alarm, misunderstanding and overreaction. The apparent epidemic levels of the behavior have exposed a structural weakness of psychiatric care: Because self-injury is considered a “symptom,” and not a stand-alone diagnosis like depression, the testing of treatments has been haphazard and therapists have little evidence to draw on.

In the past few years, psychiatric researchers have begun to knit together the motives, underlying biology and social triggers of self-harm. The story thus far gives parents — tens of million worldwide — some insight into what is at work when they see a child with scars or burns. And it allows for the evaluation of tailored treatments: In one newly published trial, researchers in New York found that self-injury can be reduced with a specialized form of talk therapy that was invented to treat what’s known as borderline personality disorder.

“It used to be that this kind of behavior was confined to the very severely impaired, people with histories of sexual abuse, with major body alienation,” said Barent Walsh, a psychologist who was one of the first therapists to focus on treating self-injury, at The Bridge program in Marlborough, Mass., now a part of Open Sky Community Services. “Then, suddenly, it morphed into the general population, to the point where it was affecting successful kids with money. That’s when the research funding started to flow, and we’ve gotten a better handle on what’s happening.”

Joan was 13 when the cutting began. Now 16, she had greatly curtailed this routine in the past few months, she said: “But I still do it, like, every week or so.”

The most common misperception about self-injury is that it is a suicide attempt: A parent walks in on an adolescent cutting herself or himself, and the sight of blood is blinding. “A lot of people think that, but in reality, you cut for different reasons,” said Blue, 16, another high school student in the New York area, who asked that her last name be omitted. “Like, it’s the only way you know to deal with intense insecurities, or anger at yourself. Or you’re so numb as a result of depression, you can’t feel anything — and this is one thing you can feel.”

Whether this method of self-soothing is an epidemic of the social media age is still a matter of scientific debate. No surveys asking about self-harm were conducted before the mid-1980s, in part because few researchers thought to ask. (...)

This on-again, off-again pattern becomes, for about 20 percent of people who engage in it, a full-blown addiction, as powerful as an opiate habit. “Something about it was so grounding, and it was always there for me,” said Nancy Dupill, 32, who cut herself regularly for more than a decade before winding down the habit, in therapy; she now works as a peer specialist for adolescents in central Massachusetts. “I got to the point where I cut myself a lot, and when I came out of it, I couldn’t remember things that happened, like what set it off in the first place.”

People who become dependent on self-harm often come to treasure it as their one reliable comfort, therapists say. Images of blood, burns, cuts and scarring may become, paradoxically, consoling. In isolation, amid emotional turbulence, self-injury is a secret friend, one that can be summoned anytime, without permission or payment. “Unlike emotional or social pain, it’s possible to control physical pain” and its soothing effect, said Joseph Franklin, a psychologist at Florida State University.

by Benedict Carey, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Keith Negley

A New Type of Scam: Business Email Compromise

The secret to comedy, according to the old joke, is timing. The same is true of cybercrime.

Mark learned this the hard way in 2017. He runs a real estate company in Seattle and asked us not to include his last name because of the possible repercussions for his business.

"The idea that someone was effectively able to dupe you ... is embarrassing," he says. "We're still kind of scratching our head over how it happened."

"The idea that someone was effectively able to dupe you ... is embarrassing," he says. "We're still kind of scratching our head over how it happened."It started when someone hacked into his email conversation with a business partner. But the hackers didn't take over the email accounts. Instead, they lurked, monitoring the conversation and waiting for an opportunity.

When Mark and his partner mentioned a $50,000 disbursement owed to the partner, the scammers made their move.

"They were able to insert their own wiring instructions," he says. Pretending to be Mark's partner, they asked him to send the money to a bank account they controlled.

"The cadence and the timing and the email was so normal that it wasn't suspicious at all. It was just like we were continuing to have a conversation, but I just wasn't having it with the person I thought I was," Mark says.

He didn't realize what had happened until his partner said he'd never gotten the money. "Oh, it was just a cold sweat," he says.

By the time they alerted the bank, the $50,000 was long gone, transferred overseas.

It turned out Mark was on the vanguard of a growing wave of something called "business email compromise," or BEC. It's a category of scam that uses phony emails to trick employees at companies to wire money to the wrong accounts. The FBI's Internet Crime Complaint Center says reported BEC amounted to more than $1.2 billion in 2018, nearly triple the figure in 2016. (...)

"What we've seen in 2019 is that the wave that's breaking is primarily focused around social engineering," says Patrick Peterson, CEO of Agari, a company that specializes in protecting corporate email systems. "Social engineering" is hacker-speak for scams that rely less on technical tricks and more on taking advantage of human vulnerabilities.

"It's not so much having the most sophisticated, evil technology. It's using our own trust and desire to communicate with others against us," Peterson says.

In the past, scammers have pretended to be business partners and CEOs, urging employees to send money for an urgent matter. But lately there has been a trend toward what Agari calls "vendor email compromise" — scammers pretending to be part of a company's supply chain.

by Martin Kaste, NPR | Read more:

Image: Deborah Lee

Terry O'Neill (1938-2019)

Photographer of swinging 60s Terry O'Neill dies aged 81 (Guardian)

[ed. See also: Terry O'Neill: a life in pictures; and O'Neill images from the National Portrait Gallery.]

Sunday, November 17, 2019

The Future of Live Music Lives on Your Smartphone

Think back to the first time you saw a high-definition TV program.

After a lifetime of looking at standard-definition shows (and perhaps fuzzy black-and-white ones before that), you likely felt that a new world was opening in front of your eyes, allowing you to see television in much the same way you take in the real world. You probably never wanted to go back.

Something similar happened to me recently, at a concert for the rock band Incubus.

Incubus, who you may remember from their seminal 1999’s single “Drive,” use a new technology from a startup called Mixhalo to enhance its live shows. All concertgoers have to do is install Mixhalo’s app, connect to the concert, and plug in their headphones. I got to test it out when Incubus recently played in New York, and was greeted with a live-music experience like none I’d ever had.

Incubus, who you may remember from their seminal 1999’s single “Drive,” use a new technology from a startup called Mixhalo to enhance its live shows. All concertgoers have to do is install Mixhalo’s app, connect to the concert, and plug in their headphones. I got to test it out when Incubus recently played in New York, and was greeted with a live-music experience like none I’d ever had.Using the app, I could hear the mix of the musicians coming right from the venue’s soundboard, as the band themselves were hearing it. I could choose to listen to specific mixes of the show, swapping between lead guitar parts, pulling out singer Brandon Boyd’s vocals for the most emphatic parts, and at other times listening in to the “alien sounds,” as DJ Chris Kilmore calls them, that he produces and are often lost in the cacophony of a live performance. I could turn up or down the volume of the show and flit between mixes as much as I’d like. I was standing to the side of the stage, and although the band was facing outwards, it felt as if they were just playing for me, and I managed to somehow forget there were thousands of fans around me. I could actually make out what Boyd was singing, and hear the drum lines, instead of being subjected to the multitude of adoring fans, who, although not lacking for energy or enthusiasm, often don’t have the vocal chops or rhythmic skills of the band onstage.

Mixhalo changes the fan’s experience at live events, allowing them to hear the show as the band (or sound engineer) intended. It no longer matters whether Madison Square Garden has poor acoustics or if you’re sitting too far away from the PA system—with Mixhalo, every seat in every venue can hear perfectly. Thanks to Incubus.

How Mixhalo came to be

Mike Einziger, the guitarist in Incubus, told Quartz that he had a slow-burning realization of the idea for Mixhalo over the better part of two decades. Around 2000, he, and many other touring musicians, started wearing radio packs and headphones that allowed them to hear the soundboard’s mix of what they were playing at concerts. Live venues are often so loud that without technology like this, it can be difficult to hear yourself—even with onstage speakers (called monitors) pointed at you—let alone your bandmates.

Eventually, that germinated into an idea. “Onstage we’re having a different experience than people are having in the audience,” Einziger said. “I had the thought in my head that it would be interesting if people in the audience could hear what I’m hearing.”

In 2016, while rehearsing for the Grammys, the band had a guest listen to one of their rehearsals; a member of their crew asked if he’d like to borrow a spare radio pack so he could hear what the rehearsal sounded like to the musicians. Einziger had “an epiphany” when he wondered if it would be possible to replicate the radio pack on regular smartphones. (...)

How it works

Although your phone sees a Mixhalo network like any other wifi network, the company’s proprietary technology is actually closer to how a radio network functions. On a wifi or cellular network, the more people connecting to an access point, the slower the connection to each individual device will be, as each person vies for the amount of data they need. With a radio broadcast, that doesn’t happen—the number of people who tune in to a radio broadcast from their car doesn’t affect the quality of anyone else listening. “The first person who logs on to the Mixhalo network will have the same experience as the 10,000th,” Simpson said.

This primarily comes down to the way the network is set up. On wifi or cellular, you have to apportion just about as much bandwidth for information flowing to a smartphone as coming out of it. Using the internet is a constant exchange of data, whether you’re listening to a song on Spotify and the network needs to know where you are and whether you’re moving, or if you’re playing a game online and the network needs to send you game visuals that change as you move the controls. With Mixhalo, the majority of the data is just flowing to devices, with little coming back in return. This allows for considerably more people to connect to a single Mixhalo access point to stream high-quality audio than they would if they were all connected over traditional wifi.

Simpson said that just about any band would be covered by Mixhalo, as the technology could theoretically stream up to 150 different channels at once. Even the London Philharmonic Orchestra doesn’t have that many musicians in it. But this could prove massively useful for events where many people want to hear one thing—that could be as simple as providing everyone in an audience with good sound, even if they’re in the nosebleed seats, or as complex as a UN general assembly, where a diplomat’s speech could be translated into dozens of languages at once.

by Mike Murphy, Quartz | Read more:

Image: Erik Kabik Photography/Mediapunch Friday, November 15, 2019

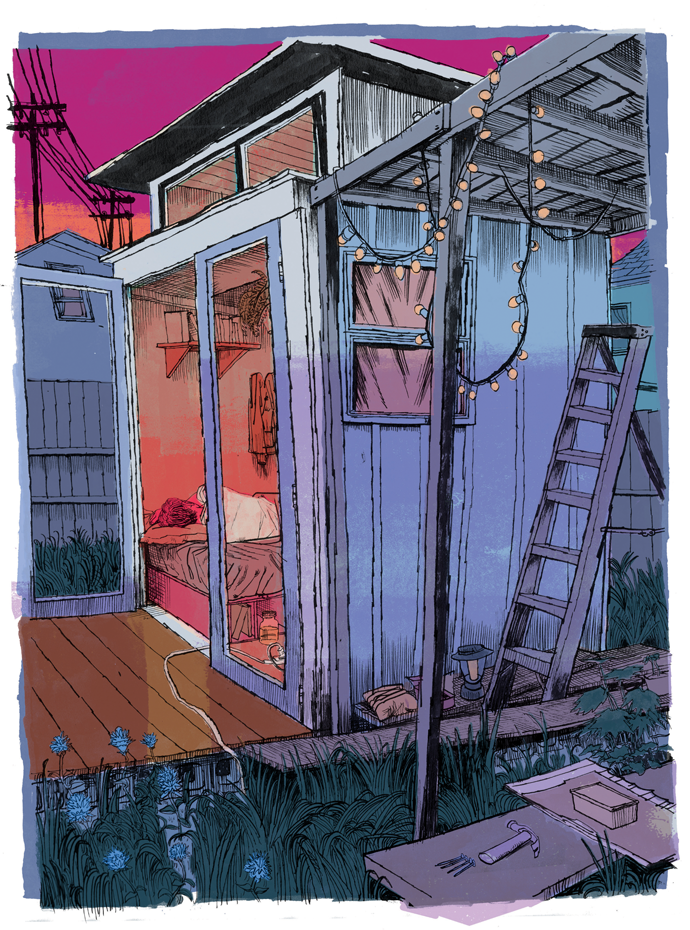

Gimme Shelter

That year, the year of the Ghost Ship fire, I lived in a shack. I’d found the place just as September’s Indian summer was giving way to a wet October. There was no plumbing or running water to wash my hands or brush my teeth before sleep. Electricity came from an extension cord that snaked through a yard of coyote mint and monkey flower and up into a hole I’d drilled in my floorboards. The structure was smaller than a cell at San Quentin—a tiny house or a huge coffin, depending on how you looked at it—four by eight and ten feet tall, so cramped it fit little but a mattress, my suit jackets and ties, a space heater, some novels, and the mason jar I peed in.

The exterior of my hermitage was washed the color of runny egg yolk. Two redwood French doors with plexiglass windows hung cockeyed from creaky hinges at the entrance, and a combination lock provided meager security against intruders. White beadboard capped the roof, its brim shading a front porch set on cinder blocks.

After living on the East Coast for eight years, I’d recently left New York City to take a job at an investigative reporting magazine in San Francisco. If it seems odd that I was a fully employed editor who lived in a thirty-two-square-foot shack, that’s precisely the point: my situation was evidence of how distorted the Bay Area housing market had become, the brutality inflicted upon the poor now trickling up to everyone but the super-rich. The problem was nationwide, although, as Californians tend to do, they’d taken this trend to an extreme. Across the state, a quarter of all apartment dwellers spent half of their incomes on rent. Nearly half of the country’s unsheltered homeless population lived in California, even while the state had the highest concentration of billionaires in the nation. In the Bay Area, including West Oakland, where my shack was located, the crisis was most acute. Tent cities had sprung up along the sidewalks, swarming with capitalism’s refugees. Telegraph, Mission, Market, Grant: every bridge and overpass had become someone’s roof.

After living on the East Coast for eight years, I’d recently left New York City to take a job at an investigative reporting magazine in San Francisco. If it seems odd that I was a fully employed editor who lived in a thirty-two-square-foot shack, that’s precisely the point: my situation was evidence of how distorted the Bay Area housing market had become, the brutality inflicted upon the poor now trickling up to everyone but the super-rich. The problem was nationwide, although, as Californians tend to do, they’d taken this trend to an extreme. Across the state, a quarter of all apartment dwellers spent half of their incomes on rent. Nearly half of the country’s unsheltered homeless population lived in California, even while the state had the highest concentration of billionaires in the nation. In the Bay Area, including West Oakland, where my shack was located, the crisis was most acute. Tent cities had sprung up along the sidewalks, swarming with capitalism’s refugees. Telegraph, Mission, Market, Grant: every bridge and overpass had become someone’s roof.Down these same streets, tourists scuttered along on Segways and techies surfed the hills on motorized longboards, transformed by their wealth into children, just as the sidewalk kids in cardboard boxes on Haight or in People’s Park aged overnight into decrepit adults, the former racing toward the future, the latter drifting away from it.

To my mother and girlfriend back East, the “shack situation” was a problem to be solved. “Can we help you find another place?” “Can you just find roommates and live in a house?” But the shack was the solution, not the problem. (...)

Growing up in rural upstate New York, raised on food stamps and free school lunches, my dad off to prison for a spell, I never met anyone who made a living in publishing. But in 2007 I was accepted into U.C. Berkeley’s graduate program in journalism. I saw the school, and the scholarship it offered, as a possible entrée to a world I had believed wasn’t available to working-class people like me. So, at age twenty-five, I stuffed my Toyota Camry with books and clothes, and, accompanied by my then girlfriend and $500 in savings, I drove west to a state I’d never even visited, hoping Cormac McCarthy was right when he wrote, in No Country for Old Men, that the “best way to live in California is to be from somewheres else.”

The Great Recession had not yet hit, and cheap housing was easy enough to find, even for someone with no credit or bank account. When my girlfriend and I broke up, I landed at a ratty mansion, Fort Awesome, in South Berkeley. My rent for one of the mansion’s eleven bedrooms was about $300 a month. There was an outdoor kitchen the size of a large cottage, three guest shacks, and a wood-fired hot tub built from a redwood wine vat. About thirty people lived on the compound, including a few children. The adult residents were a mix of hippies, crusties, anarchists, outcast techies, chemistry grad students, addicts, and activists—a cohort that shouldn’t have lasted a day, but in fact had lasted six years, ever since some of the residents had banded together and, with the help of a community land trust, bought the plot for $600,000. (Today, the property is worth about $4 million.)

I was unwittingly among the vanguard of a wave of gentrification—a transient “creative” living in a “rough” neighborhood not yet fully colonized by the white middle class—and sometimes it was tense. I almost brawled one night with three teens who shoved me out front of a liquor store; another night I fought off a mugger and came home with a black eye. But otherwise the Bay was astonishingly convivial—for the first time in Oakland’s history, the city’s populations of African-American, Latino, Asian, and white residents were almost exactly equal in size—and I fell in love with dozens of squats, warehouses, galleries, and underground bars, where black hyphy kids and white gutter punks and queer Asian ravers all hung out and partied together, paving the way for later spaces like Ghost Ship. It felt like the perfect time to be there, like I imagined the Eighties on New York City’s Lower East Side. (...)

The Great Recession had not yet hit, and cheap housing was easy enough to find, even for someone with no credit or bank account. When my girlfriend and I broke up, I landed at a ratty mansion, Fort Awesome, in South Berkeley. My rent for one of the mansion’s eleven bedrooms was about $300 a month. There was an outdoor kitchen the size of a large cottage, three guest shacks, and a wood-fired hot tub built from a redwood wine vat. About thirty people lived on the compound, including a few children. The adult residents were a mix of hippies, crusties, anarchists, outcast techies, chemistry grad students, addicts, and activists—a cohort that shouldn’t have lasted a day, but in fact had lasted six years, ever since some of the residents had banded together and, with the help of a community land trust, bought the plot for $600,000. (Today, the property is worth about $4 million.)

I was unwittingly among the vanguard of a wave of gentrification—a transient “creative” living in a “rough” neighborhood not yet fully colonized by the white middle class—and sometimes it was tense. I almost brawled one night with three teens who shoved me out front of a liquor store; another night I fought off a mugger and came home with a black eye. But otherwise the Bay was astonishingly convivial—for the first time in Oakland’s history, the city’s populations of African-American, Latino, Asian, and white residents were almost exactly equal in size—and I fell in love with dozens of squats, warehouses, galleries, and underground bars, where black hyphy kids and white gutter punks and queer Asian ravers all hung out and partied together, paving the way for later spaces like Ghost Ship. It felt like the perfect time to be there, like I imagined the Eighties on New York City’s Lower East Side. (...)

Across the street from my shack was Easy Liquor. A few weeks earlier, I’d been walking home in a downpour when I stumbled on a shirtless man circling its parking lot, shouting angrily, his hands clutched over his stomach. I asked if I could help. “Pull it out!” he shouted, and he shook his fists at me, revealing a knife handle where his belly button should have been. Another evening, on West MacArthur, I watched a large man shove his shopping cart into the path of a techie on a bicycle. The techie swerved and fell, and the homeless man put one foot on his victim’s chest and tugged at his Google laptop bag. “Help me!” the techie shouted as they played tug-of-war. I sprinted over and pushed the two men apart, yelling, “Get the fuck out of here and don’t come back!” I was talking to them both.

My neighbors’ homes were mostly blighted bungalows with peeling stucco, dust-bowl lawns, and barbed-wire fences. Men bench-pressed weights in driveways. Cars left on the street overnight would often appear the next morning with smashed windshields and cinder-block tires. The neighborhood’s boundaries were drawn by the “wrong” side of the BART train tracks and Telegraph Avenue to the east, bleak San Pablo Avenue to the west, and its southern and northern borders were marked by 35th Street and Ashby Avenue, beyond which were the newly bourgeois enclaves of Temescal and Emeryville. It wasn’t really a coherent neighborhood but its proximity to BART and the general scarcity of housing in the Bay had led developers to try to rebrand it “NOBE” (North Oakland Berkeley Emeryville), an absurd neologism I never once heard used except by real estate boosters.

Yet the rebranding was working, at least on paper. I seldom saw well-to-do white people on the streets, except when they were hurrying home or being mugged, but two- and three-bedroom cottages in the neighborhood were going on the market for $1.5 million, $2 million, and sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars more, often bought in cash by coders or executives who’d come east from San Francisco or west from the eastern seaboard to work for LinkedIn or Twitter or Atlassian or Oracle. As soon as a for sale sign went down, the ghetto bungalow behind it would be remodeled, landscaped, and encircled by a steel gate. The new inhabitants would only appear in public twice a day. In the morning, the jaws of their gated driveways opened, spitting tasteless Teslas and BMWs out into the streets, their drivers racing past the Palms, the Bay View, the Nights Inn, and Easy Liquor en route to the freeway or BART’s police-patrolled parking lot. At night, their gates would open to swallow them again, so they might sleep safely in the bellies of the beasts they called home, safe from the chaos outside.

At the end of our block was a monument to the housing wars: an eight-story, 105-unit, half-completed condo building that no one had ever lived in, and that no one ever would, casting its Hindenburg-size shadow over my shack. Just before my return to California, and amid rumors of anti-gentrification arsons, it mysteriously caught fire. This blaze devoured more than $35 million in labor and materials, and now the steel skeleton bowed and buckled. The entire top floor had collapsed, and the facade was seared with black smoke stains. (When someone torched this same building again several months later, police decided definitively that it was arson. I recall riding through the smoke on my bike that day.) As a result, the funders, Holliday Development, had ringed the property’s perimeter with chain-link and posted a twenty-four-hour armed sentry in a little matchbox booth inside the fence, a fat, tired man who waved to me cheerily when I cycled by.

Beside the half-destroyed condo complex was the 580 on-ramp to San Francisco. Clustered there on the highway’s margins was yet another of the city’s countless, nameless tent cities, a patchwork of a few dozen tarps and tents lit up at night by flaming oil drums. Beyond this homeless depot was Home Depot. I locked my bike outside the store and wandered the immaculate fluorescent-lit aisles. I bought four sheets of O.S.B. board, a box of three-inch drywall screws, and an armload of two-by-fours. Outside with my haul, I heard the loud thunk-thunk-thunk of E.D.M. and the squall of rubber tires skidding into the parking lot—Jenny’s Jeep, a crack down the center of the windshield like a busted smile, swerved into view and stopped in front of me, Jenny’s grinning face and tousled black hair framed by the rolled-down window.

“Check out this cute work outfit I bought,” she said, jumping out of the Jeep and modeling a pair of black thrift-store overalls.

“Portrait of an urban homesteader,” I said. (...)

Living in the shack, I came to realize that part of my motivation in moving back to the Bay Area was an urge to return to my younger self, a desire for freedom from the pressures of adulthood. After grad school at Berkeley, I’d gone to New York City, wanting to be a writer—but there weren’t, and aren’t, really full-time jobs for writers, not the kind I wanted to be, anyway. So I chose to become an editor, which seemed to be a way to split the difference between the precarity of the artist and the banality of the white-collar wage slave. But my role in the middle class was by no means secure or guaranteed no matter how hard I worked, and I had come to feel deceived by the mirage of upward mobility: after almost a decade of uninterrupted employment, of doing everything “right,” I owned no property, I had no stocks, no investments, no wealth, no inheritance, no safety net or support system beyond a few thousand dollars in my savings account. One disaster—being fired, sustaining a serious injury, needing to help out a desperate friend—could wipe me out, and if that happened, what would I have gained in a decade as an editor? I had decided I no longer cared about ever becoming middle-class; the cost of earning a living this way was too high. The terror of poverty had become far less frightening than the wages of having wasted my life.

“It is a feeling of relief, almost of pleasure, at knowing yourself at last genuinely down and out,” George Orwell wrote in Down and Out in Paris and London. “You have talked so often of going to the dogs—and well, here are the dogs, and you have reached them, and you can stand it. It takes off a lot of anxiety.” (...)

The powerful thing about smallness, it occurred to me, isn’t actually smallness for its own sake—the point, instead, is a matter of scale. If you reduce the size of your life enough, then the smallest change can be a profound improvement. Yet the hardest thing is to recognize your smallness without being diminished by it. In my shack I was always balancing that tension—I didn’t want to become so small that I disappeared, I just wanted to hide for a little while.

My neighbors’ homes were mostly blighted bungalows with peeling stucco, dust-bowl lawns, and barbed-wire fences. Men bench-pressed weights in driveways. Cars left on the street overnight would often appear the next morning with smashed windshields and cinder-block tires. The neighborhood’s boundaries were drawn by the “wrong” side of the BART train tracks and Telegraph Avenue to the east, bleak San Pablo Avenue to the west, and its southern and northern borders were marked by 35th Street and Ashby Avenue, beyond which were the newly bourgeois enclaves of Temescal and Emeryville. It wasn’t really a coherent neighborhood but its proximity to BART and the general scarcity of housing in the Bay had led developers to try to rebrand it “NOBE” (North Oakland Berkeley Emeryville), an absurd neologism I never once heard used except by real estate boosters.

Yet the rebranding was working, at least on paper. I seldom saw well-to-do white people on the streets, except when they were hurrying home or being mugged, but two- and three-bedroom cottages in the neighborhood were going on the market for $1.5 million, $2 million, and sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars more, often bought in cash by coders or executives who’d come east from San Francisco or west from the eastern seaboard to work for LinkedIn or Twitter or Atlassian or Oracle. As soon as a for sale sign went down, the ghetto bungalow behind it would be remodeled, landscaped, and encircled by a steel gate. The new inhabitants would only appear in public twice a day. In the morning, the jaws of their gated driveways opened, spitting tasteless Teslas and BMWs out into the streets, their drivers racing past the Palms, the Bay View, the Nights Inn, and Easy Liquor en route to the freeway or BART’s police-patrolled parking lot. At night, their gates would open to swallow them again, so they might sleep safely in the bellies of the beasts they called home, safe from the chaos outside.

At the end of our block was a monument to the housing wars: an eight-story, 105-unit, half-completed condo building that no one had ever lived in, and that no one ever would, casting its Hindenburg-size shadow over my shack. Just before my return to California, and amid rumors of anti-gentrification arsons, it mysteriously caught fire. This blaze devoured more than $35 million in labor and materials, and now the steel skeleton bowed and buckled. The entire top floor had collapsed, and the facade was seared with black smoke stains. (When someone torched this same building again several months later, police decided definitively that it was arson. I recall riding through the smoke on my bike that day.) As a result, the funders, Holliday Development, had ringed the property’s perimeter with chain-link and posted a twenty-four-hour armed sentry in a little matchbox booth inside the fence, a fat, tired man who waved to me cheerily when I cycled by.

Beside the half-destroyed condo complex was the 580 on-ramp to San Francisco. Clustered there on the highway’s margins was yet another of the city’s countless, nameless tent cities, a patchwork of a few dozen tarps and tents lit up at night by flaming oil drums. Beyond this homeless depot was Home Depot. I locked my bike outside the store and wandered the immaculate fluorescent-lit aisles. I bought four sheets of O.S.B. board, a box of three-inch drywall screws, and an armload of two-by-fours. Outside with my haul, I heard the loud thunk-thunk-thunk of E.D.M. and the squall of rubber tires skidding into the parking lot—Jenny’s Jeep, a crack down the center of the windshield like a busted smile, swerved into view and stopped in front of me, Jenny’s grinning face and tousled black hair framed by the rolled-down window.

“Check out this cute work outfit I bought,” she said, jumping out of the Jeep and modeling a pair of black thrift-store overalls.

“Portrait of an urban homesteader,” I said. (...)

Living in the shack, I came to realize that part of my motivation in moving back to the Bay Area was an urge to return to my younger self, a desire for freedom from the pressures of adulthood. After grad school at Berkeley, I’d gone to New York City, wanting to be a writer—but there weren’t, and aren’t, really full-time jobs for writers, not the kind I wanted to be, anyway. So I chose to become an editor, which seemed to be a way to split the difference between the precarity of the artist and the banality of the white-collar wage slave. But my role in the middle class was by no means secure or guaranteed no matter how hard I worked, and I had come to feel deceived by the mirage of upward mobility: after almost a decade of uninterrupted employment, of doing everything “right,” I owned no property, I had no stocks, no investments, no wealth, no inheritance, no safety net or support system beyond a few thousand dollars in my savings account. One disaster—being fired, sustaining a serious injury, needing to help out a desperate friend—could wipe me out, and if that happened, what would I have gained in a decade as an editor? I had decided I no longer cared about ever becoming middle-class; the cost of earning a living this way was too high. The terror of poverty had become far less frightening than the wages of having wasted my life.

“It is a feeling of relief, almost of pleasure, at knowing yourself at last genuinely down and out,” George Orwell wrote in Down and Out in Paris and London. “You have talked so often of going to the dogs—and well, here are the dogs, and you have reached them, and you can stand it. It takes off a lot of anxiety.” (...)

The powerful thing about smallness, it occurred to me, isn’t actually smallness for its own sake—the point, instead, is a matter of scale. If you reduce the size of your life enough, then the smallest change can be a profound improvement. Yet the hardest thing is to recognize your smallness without being diminished by it. In my shack I was always balancing that tension—I didn’t want to become so small that I disappeared, I just wanted to hide for a little while.

by Wes Enzinna, Harper's | Read more:

Image: Matt Rota

Against Economics

There is a growing feeling, among those who have the responsibility of managing large economies, that the discipline of economics is no longer fit for purpose. It is beginning to look like a science designed to solve problems that no longer exist.

A good example is the obsession with inflation. Economists still teach their students that the primary economic role of government—many would insist, its only really proper economic role—is to guarantee price stability. We must be constantly vigilant over the dangers of inflation. For governments to simply print money is therefore inherently sinful. If, however, inflation is kept at bay through the coordinated action of government and central bankers, the market should find its “natural rate of unemployment,” and investors, taking advantage of clear price signals, should be able to ensure healthy growth. These assumptions came with the monetarism of the 1980s, the idea that government should restrict itself to managing the money supply, and by the 1990s had come to be accepted as such elementary common sense that pretty much all political debate had to set out from a ritual acknowledgment of the perils of government spending. This continues to be the case, despite the fact that, since the 2008 recession, central banks have been printing money frantically in an attempt to create inflation and compel the rich to do something useful with their money, and have been largely unsuccessful in both endeavors.

We now live in a different economic universe than we did before the crash. Falling unemployment no longer drives up wages. Printing money does not cause inflation. Yet the language of public debate, and the wisdom conveyed in economic textbooks, remain almost entirely unchanged.

One expects a certain institutional lag. Mainstream economists nowadays might not be particularly good at predicting financial crashes, facilitating general prosperity, or coming up with models for preventing climate change, but when it comes to establishing themselves in positions of intellectual authority, unaffected by such failings, their success is unparalleled. One would have to look at the history of religions to find anything like it. To this day, economics continues to be taught not as a story of arguments—not, like any other social science, as a welter of often warring theoretical perspectives—but rather as something more like physics, the gradual realization of universal, unimpeachable mathematical truths. “Heterodox” theories of economics do, of course, exist (institutionalist, Marxist, feminist, “Austrian,” post-Keynesian…), but their exponents have been almost completely locked out of what are considered “serious” departments, and even outright rebellions by economics students (from the post-autistic economics movement in France to post-crash economics in Britain) have largely failed to force them into the core curriculum.

One expects a certain institutional lag. Mainstream economists nowadays might not be particularly good at predicting financial crashes, facilitating general prosperity, or coming up with models for preventing climate change, but when it comes to establishing themselves in positions of intellectual authority, unaffected by such failings, their success is unparalleled. One would have to look at the history of religions to find anything like it. To this day, economics continues to be taught not as a story of arguments—not, like any other social science, as a welter of often warring theoretical perspectives—but rather as something more like physics, the gradual realization of universal, unimpeachable mathematical truths. “Heterodox” theories of economics do, of course, exist (institutionalist, Marxist, feminist, “Austrian,” post-Keynesian…), but their exponents have been almost completely locked out of what are considered “serious” departments, and even outright rebellions by economics students (from the post-autistic economics movement in France to post-crash economics in Britain) have largely failed to force them into the core curriculum.As a result, heterodox economists continue to be treated as just a step or two away from crackpots, despite the fact that they often have a much better record of predicting real-world economic events. What’s more, the basic psychological assumptions on which mainstream (neoclassical) economics is based—though they have long since been disproved by actual psychologists—have colonized the rest of the academy, and have had a profound impact on popular understandings of the world.

Nowhere is this divide between public debate and economic reality more dramatic than in Britain, which is perhaps why it appears to be the first country where something is beginning to crack. It was center-left New Labour that presided over the pre-crash bubble, and voters’ throw-the-bastards-out reaction brought a series of Conservative governments that soon discovered that a rhetoric of austerity—the Churchillian evocation of common sacrifice for the public good—played well with the British public, allowing them to win broad popular acceptance for policies designed to pare down what little remained of the British welfare state and redistribute resources upward, toward the rich. “There is no magic money tree,” as Theresa May put it during the snap election of 2017—virtually the only memorable line from one of the most lackluster campaigns in British history. The phrase has been repeated endlessly in the media, whenever someone asks why the UK is the only country in Western Europe that charges university tuition, or whether it is really necessary to have quite so many people sleeping on the streets.

The truly extraordinary thing about May’s phrase is that it isn’t true. There are plenty of magic money trees in Britain, as there are in any developed economy. They are called “banks.” Since modern money is simply credit, banks can and do create money literally out of nothing, simply by making loans. Almost all of the money circulating in Britain at the moment is bank-created in this way. Not only is the public largely unaware of this, but a recent survey by the British research group Positive Money discovered that an astounding 85 percent of members of Parliament had no idea where money really came from (most appeared to be under the impression that it was produced by the Royal Mint).

Economists, for obvious reasons, can’t be completely oblivious to the role of banks, but they have spent much of the twentieth century arguing about what actually happens when someone applies for a loan. One school insists that banks transfer existing funds from their reserves, another that they produce new money, but only on the basis of a multiplier effect (so that your car loan can still be seen as ultimately rooted in some retired grandmother’s pension fund). Only a minority—mostly heterodox economists, post-Keynesians, and modern money theorists—uphold what is called the “credit creation theory of banking”: that bankers simply wave a magic wand and make the money appear, secure in the confidence that even if they hand a client a credit for $1 million, ultimately the recipient will put it back in the bank again, so that, across the system as a whole, credits and debts will cancel out. Rather than loans being based in deposits, in this view, deposits themselves were the result of loans.

The one thing it never seemed to occur to anyone to do was to get a job at a bank, and find out what actually happens when someone asks to borrow money. In 2014 a German economist named Richard Werner did exactly that, and discovered that, in fact, loan officers do not check their existing funds, reserves, or anything else. They simply create money out of thin air, or, as he preferred to put it, “fairy dust.”

That year also appears to have been when elements in Britain’s notoriously independent civil service decided that enough was enough. The question of money creation became a critical bone of contention. The overwhelming majority of even mainstream economists in the UK had long since rejected austerity as counterproductive (which, predictably, had almost no impact on public debate). But at a certain point, demanding that the technocrats charged with running the system base all policy decisions on false assumptions about something as elementary as the nature of money becomes a little like demanding that architects proceed on the understanding that the square root of 47 is actually π. Architects are aware that buildings would start falling down. People would die.

Before long, the Bank of England (the British equivalent of the Federal Reserve, whose economists are most free to speak their minds since they are not formally part of the government) rolled out an elaborate official report called “Money Creation in the Modern Economy,” replete with videos and animations, making the same point: existing economics textbooks, and particularly the reigning monetarist orthodoxy, are wrong. The heterodox economists are right. Private banks create money. Central banks like the Bank of England create money as well, but monetarists are entirely wrong to insist that their proper function is to control the money supply. In fact, central banks do not in any sense control the money supply; their main function is to set the interest rate—to determine how much private banks can charge for the money they create. Almost all public debate on these subjects is therefore based on false premises. For example, if what the Bank of England was saying were true, government borrowing didn’t divert funds from the private sector; it created entirely new money that had not existed before.

One might have imagined that such an admission would create something of a splash, and in certain restricted circles, it did. Central banks in Norway, Switzerland, and Germany quickly put out similar papers. Back in the UK, the immediate media response was simply silence. The Bank of England report has never, to my knowledge, been so much as mentioned on the BBC or any other TV news outlet. Newspaper columnists continued to write as if monetarism was self-evidently correct. Politicians continued to be grilled about where they would find the cash for social programs. It was as if a kind of entente cordiale had been established, in which the technocrats would be allowed to live in one theoretical universe, while politicians and news commentators would continue to exist in an entirely different one.

Still, there are signs that this arrangement is temporary. England—and the Bank of England in particular—prides itself on being a bellwether for global economic trends. Monetarism itself got its launch into intellectual respectability in the 1970s after having been embraced by Bank of England economists. From there it was ultimately adopted by the insurgent Thatcher regime, and only after that by Ronald Reagan in the United States, and it was subsequently exported almost everywhere else.

It is possible that a similar pattern is reproducing itself today.

by David Graeber, NYRB | Read more:

Image: Dana Schutz: Men’s Retreat, 2005

Image: Dick Van Duijn

Thursday, November 14, 2019

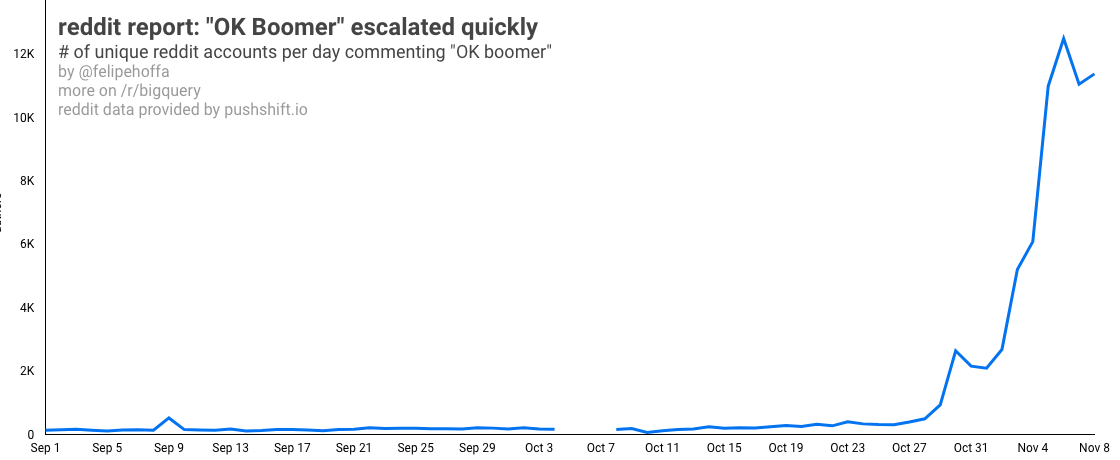

“OK Boomer” Escalated Quickly

“OK Boomer” escalated quickly — a reddit+BigQuery report (Medium)

Image: uncredited

[ed. Evolution of a meme.]

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)