Monday, July 6, 2020

Bountygate and Afghanistan

Bountygate: Scapegoating Systemic Military Failure in Afghanistan (Consortium News)

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Our Minds Aren’t Equipped for This Kind of Reopening

Our Minds Aren’t Equipped for This Kind of Reopening (The Atlantic)

Image: Shutterstock/NIH/The Atlantic

Sunday, July 5, 2020

in time of daffodils (who know

the goal of living is to grow)

forgetting why, remember how

in time of lilacs who proclaim

the aim of waking is to dream,

remember so (forgetting seem)

in time of roses (who amaze

our now and here with paradise)

forgetting if, remember yes

in time of all sweet things beyond

whatever mind may comprehend,

remember seek (forgetting find)

and in a mystery to be

(when time from time shall set us free)

forgetting me, remember me

~ e. e. cummings

Saturday, July 4, 2020

Savage Love: Kinked Gays

My new boyfriend just opened up to me about his kinks. Nothing crazy: just bondage and humiliation. While he usually meets and dates guys off kinky dating sites we met “the old fashioned way” a few months before COVID-19 slammed us here in Chicago: at a potluck dinner party thrown by a mutual straight lady friend. Your name came up during the conversation about his interests: he told me he was taking your advice and “laying his kink cards on the table” before I had made too much of an emotional commitment. What’s interesting to me, Dan, is how often this happens. My boyfriend is easily the fourth guy I’ve dated in the last few years who laid down the exact same kink cards: wants to be tied up, wants to be called names, wants to be hurt. I’m learning to tie knots and getting better at calling him names when we have sex and I actually really enjoying spanking him. But I was talking with a friend—our straight lady mutual (with the boyfriend’s okay!)—and she told me she’s never had a straight guy open up to her about wanting to be tied up abused. Are gay guys just kinkier?

Talking Over Perversions

I have a theory…

When we’re boys… before we’re ready to come out… we’re suddenly attracted to other boy. And that’s something we usually feel pretty panicked about. It would be nice that first same-sex crush was something a boy could experience without feelings of dread or terror, TOP, but that’s not how it works for most of us. We’re keenly aware that should the object of our desire realize it—if the boy we’re attracted realizes what we’re feeling, if we give ourselves away with a stray look—the odds of that boy reacting badly or even violently are high. Even if you think the boy might not react violently, even if you suspect the boy you’re crushing on might be gay himself, the stakes are too high to risk making any sort of move. So we stew with feelings of lust and fear.

When we’re boys… before we’re ready to come out… we’re suddenly attracted to other boy. And that’s something we usually feel pretty panicked about. It would be nice that first same-sex crush was something a boy could experience without feelings of dread or terror, TOP, but that’s not how it works for most of us. We’re keenly aware that should the object of our desire realize it—if the boy we’re attracted realizes what we’re feeling, if we give ourselves away with a stray look—the odds of that boy reacting badly or even violently are high. Even if you think the boy might not react violently, even if you suspect the boy you’re crushing on might be gay himself, the stakes are too high to risk making any sort of move. So we stew with feelings of lust and fear.

Sexual desire can make anyone feel fearful and powerless—we’re literally powerless to control these feelings (while we can and must control how we act on these feelings)—but desire and fear are stirred together for us gay boys to much greater degree than they are for straight boys. We fear being found out, we fear being called names, we fear being outed, we fear being physically hurt. And the person we fear most is the person we have a crush on. A significant number of gay guys wind up imprinting on that heady and very confusing mix of desire and fear. The erotic imaginations of guys like your boyfriend seize on those fears and eroticize them. And then, in adulthood, your boyfriend want to re-experience those feelings, that heady mix of desire and fear, with a loving partner he trusts. The gay boy who feared being hurt by the person he was attracted to becomes the gay man who wants to be hurt—in a limited, controlled, consensual and safe way—by the man he’s with.

Talking Over Perversions

I have a theory…

When we’re boys… before we’re ready to come out… we’re suddenly attracted to other boy. And that’s something we usually feel pretty panicked about. It would be nice that first same-sex crush was something a boy could experience without feelings of dread or terror, TOP, but that’s not how it works for most of us. We’re keenly aware that should the object of our desire realize it—if the boy we’re attracted realizes what we’re feeling, if we give ourselves away with a stray look—the odds of that boy reacting badly or even violently are high. Even if you think the boy might not react violently, even if you suspect the boy you’re crushing on might be gay himself, the stakes are too high to risk making any sort of move. So we stew with feelings of lust and fear.

When we’re boys… before we’re ready to come out… we’re suddenly attracted to other boy. And that’s something we usually feel pretty panicked about. It would be nice that first same-sex crush was something a boy could experience without feelings of dread or terror, TOP, but that’s not how it works for most of us. We’re keenly aware that should the object of our desire realize it—if the boy we’re attracted realizes what we’re feeling, if we give ourselves away with a stray look—the odds of that boy reacting badly or even violently are high. Even if you think the boy might not react violently, even if you suspect the boy you’re crushing on might be gay himself, the stakes are too high to risk making any sort of move. So we stew with feelings of lust and fear.Sexual desire can make anyone feel fearful and powerless—we’re literally powerless to control these feelings (while we can and must control how we act on these feelings)—but desire and fear are stirred together for us gay boys to much greater degree than they are for straight boys. We fear being found out, we fear being called names, we fear being outed, we fear being physically hurt. And the person we fear most is the person we have a crush on. A significant number of gay guys wind up imprinting on that heady and very confusing mix of desire and fear. The erotic imaginations of guys like your boyfriend seize on those fears and eroticize them. And then, in adulthood, your boyfriend want to re-experience those feelings, that heady mix of desire and fear, with a loving partner he trusts. The gay boy who feared being hurt by the person he was attracted to becomes the gay man who wants to be hurt—in a limited, controlled, consensual and safe way—by the man he’s with.

Inside the Invasive, Secretive “Bossware” Tracking Workers

COVID-19 has pushed millions of people to work from home, and a flock of companies offering software for tracking workers has swooped in to pitch their products to employers across the country.

The services often sound relatively innocuous. Some vendors bill their tools as “automatic time tracking” or “workplace analytics” software. Others market to companies concerned about data breaches or intellectual property theft. We’ll call these tools, collectively, “bossware.” While aimed at helping employers, bossware puts workers’ privacy and security at risk by logging every click and keystroke, covertly gathering information for lawsuits, and using other spying features that go far beyond what is necessary and proportionate to manage a workforce.

This is not OK. When a home becomes an office, it remains a home. Workers should not be subject to nonconsensual surveillance or feel pressured to be scrutinized in their own homes to keep their jobs.

What can they do?

Bossware typically lives on a computer or smartphone and has privileges to access data about everything that happens on that device. Most bossware collects, more or less, everything that the user does. We looked at marketing materials, demos, and customer reviews to get a sense of how these tools work. There are too many individual types of monitoring to list here, but we’ll try to break down the ways these products can surveil into general categories.

The broadest and most common type of surveillance is “activity monitoring.” This typically includes a log of which applications and websites workers use. It may include who they email or message—including subject lines and other metadata—and any posts they make on social media. Most bossware also records levels of input from the keyboard and mouse—for example, many tools give a minute-by-minute breakdown of how much a user types and clicks, using that as a proxy for productivity. Productivity monitoring software will attempt to assemble all of this data into simple charts or graphs that give managers a high-level view of what workers are doing.

The broadest and most common type of surveillance is “activity monitoring.” This typically includes a log of which applications and websites workers use. It may include who they email or message—including subject lines and other metadata—and any posts they make on social media. Most bossware also records levels of input from the keyboard and mouse—for example, many tools give a minute-by-minute breakdown of how much a user types and clicks, using that as a proxy for productivity. Productivity monitoring software will attempt to assemble all of this data into simple charts or graphs that give managers a high-level view of what workers are doing.

Every product we looked at has the ability to take frequent screenshots of each worker’s device, and some provide direct, live video feeds of their screens. This raw image data is often arrayed in a timeline, so bosses can go back through a worker’s day and see what they were doing at any given point. Several products also act as a keylogger, recording every keystroke a worker makes, including unsent emails and private passwords. A couple even let administrators jump in and take over remote control of a user’s desktop. These products usually don’t distinguish between work-related activity and personal account credentials, bank data, or medical information.

Some bossware goes even further, reaching into the physical world around a worker’s device. Companies that offer software for mobile devices nearly always include location tracking using GPS data. At least two services—StaffCop Enterprise and CleverControl—let employers secretly activate webcams and microphones on worker devices. (...)

Visible monitoring (...)

Invisible monitoring (...)

How common is bossware?

The worker surveillance business is not new, and it was already quite large before the outbreak of a global pandemic. While it’s difficult to assess how common bossware is, it’s undoubtedly become much more common as workers are forced to work from home due to COVID-19. Awareness Technologies, which owns InterGuard, claimed to have grown its customer base by over 300% in just the first few weeks after the outbreak. Many of the vendors we looked at exploit COVID-19 in their marketing pitches to companies.

Some of the biggest companies in the world use bossware. Hubstaff customers include Instacart, Groupon, and Ring. Time Doctor claims 83,000 users; its customers include Allstate, Ericsson, Verizon, and Re/Max. ActivTrak is used by more than 6,500 organizations, including Arizona State University, Emory University, and the cities of Denver and Malibu. Companies like StaffCop and Teramind do not disclose information about their customers, but claim to serve clients in industries like health care, banking, fashion, manufacturing, and call centers. Customer reviews of monitoring software give more examples of how these tools are used.

We don’t know how many of these organizations choose to use invisible monitoring, since the employers themselves don’t tend to advertise it. In addition, there isn’t a reliable way for workers themselves to know, since so much invisible software is explicitly designed to evade detection. Some workers have contracts that authorize certain kinds of monitoring or prevent others. But for many workers, it may be impossible to tell whether they’re being watched. Workers who are concerned about the possibility of monitoring may be safest to assume that any employer-provided device is tracking them.

The services often sound relatively innocuous. Some vendors bill their tools as “automatic time tracking” or “workplace analytics” software. Others market to companies concerned about data breaches or intellectual property theft. We’ll call these tools, collectively, “bossware.” While aimed at helping employers, bossware puts workers’ privacy and security at risk by logging every click and keystroke, covertly gathering information for lawsuits, and using other spying features that go far beyond what is necessary and proportionate to manage a workforce.

This is not OK. When a home becomes an office, it remains a home. Workers should not be subject to nonconsensual surveillance or feel pressured to be scrutinized in their own homes to keep their jobs.

What can they do?

Bossware typically lives on a computer or smartphone and has privileges to access data about everything that happens on that device. Most bossware collects, more or less, everything that the user does. We looked at marketing materials, demos, and customer reviews to get a sense of how these tools work. There are too many individual types of monitoring to list here, but we’ll try to break down the ways these products can surveil into general categories.

The broadest and most common type of surveillance is “activity monitoring.” This typically includes a log of which applications and websites workers use. It may include who they email or message—including subject lines and other metadata—and any posts they make on social media. Most bossware also records levels of input from the keyboard and mouse—for example, many tools give a minute-by-minute breakdown of how much a user types and clicks, using that as a proxy for productivity. Productivity monitoring software will attempt to assemble all of this data into simple charts or graphs that give managers a high-level view of what workers are doing.

The broadest and most common type of surveillance is “activity monitoring.” This typically includes a log of which applications and websites workers use. It may include who they email or message—including subject lines and other metadata—and any posts they make on social media. Most bossware also records levels of input from the keyboard and mouse—for example, many tools give a minute-by-minute breakdown of how much a user types and clicks, using that as a proxy for productivity. Productivity monitoring software will attempt to assemble all of this data into simple charts or graphs that give managers a high-level view of what workers are doing.Every product we looked at has the ability to take frequent screenshots of each worker’s device, and some provide direct, live video feeds of their screens. This raw image data is often arrayed in a timeline, so bosses can go back through a worker’s day and see what they were doing at any given point. Several products also act as a keylogger, recording every keystroke a worker makes, including unsent emails and private passwords. A couple even let administrators jump in and take over remote control of a user’s desktop. These products usually don’t distinguish between work-related activity and personal account credentials, bank data, or medical information.

Some bossware goes even further, reaching into the physical world around a worker’s device. Companies that offer software for mobile devices nearly always include location tracking using GPS data. At least two services—StaffCop Enterprise and CleverControl—let employers secretly activate webcams and microphones on worker devices. (...)

Visible monitoring (...)

Invisible monitoring (...)

How common is bossware?

The worker surveillance business is not new, and it was already quite large before the outbreak of a global pandemic. While it’s difficult to assess how common bossware is, it’s undoubtedly become much more common as workers are forced to work from home due to COVID-19. Awareness Technologies, which owns InterGuard, claimed to have grown its customer base by over 300% in just the first few weeks after the outbreak. Many of the vendors we looked at exploit COVID-19 in their marketing pitches to companies.

Some of the biggest companies in the world use bossware. Hubstaff customers include Instacart, Groupon, and Ring. Time Doctor claims 83,000 users; its customers include Allstate, Ericsson, Verizon, and Re/Max. ActivTrak is used by more than 6,500 organizations, including Arizona State University, Emory University, and the cities of Denver and Malibu. Companies like StaffCop and Teramind do not disclose information about their customers, but claim to serve clients in industries like health care, banking, fashion, manufacturing, and call centers. Customer reviews of monitoring software give more examples of how these tools are used.

We don’t know how many of these organizations choose to use invisible monitoring, since the employers themselves don’t tend to advertise it. In addition, there isn’t a reliable way for workers themselves to know, since so much invisible software is explicitly designed to evade detection. Some workers have contracts that authorize certain kinds of monitoring or prevent others. But for many workers, it may be impossible to tell whether they’re being watched. Workers who are concerned about the possibility of monitoring may be safest to assume that any employer-provided device is tracking them.

by Bennett Cyphers and Karen Gullo, Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) | Read more:

Image: uncredited

The Facebook Boycott and Corporate Co-Optation

In this moment of wildcat strikes, one of the largest collective-bargaining actions in the United States is being led by large corporations. Advertisers have initiated a boycott against Facebook, at the urging of civil rights groups. Ford, Hershey’s, Clorox, Starbucks, Verizon, Coca-Cola, HP, Levi Strauss, Honda, Pepsi, Microsoft, Vans, Pfizer, Adidas, and hundreds more have suspended their advertising on Facebook and Instagram. The #StopHateforProfit campaign is demanding that Facebook do a better job controlling hate speech on its platforms. Facebook has promised once again to clean up its act, but that hasn’t stopped the pressure.

It’s interesting that large corporations see value in using their power as purchasers to force changes, something their own customers might want to note for the future. And seeing Mark Zuckerberg in the crosshairs of a capital strike has a delightful quality to it. But let’s be clear: This is a cosmetic PR move from a corporate sector looking for simple, performative solutions to deep-seated persecution. Multinationals are trying to buy off protesters with empty symbols of solidarity and diversity training seminars. People are in the streets over far more than that.

It’s interesting that large corporations see value in using their power as purchasers to force changes, something their own customers might want to note for the future. And seeing Mark Zuckerberg in the crosshairs of a capital strike has a delightful quality to it. But let’s be clear: This is a cosmetic PR move from a corporate sector looking for simple, performative solutions to deep-seated persecution. Multinationals are trying to buy off protesters with empty symbols of solidarity and diversity training seminars. People are in the streets over far more than that.

It’s very unclear whether this advertising boycott represents anything close to a sacrifice for advertisers. First off, most of the brands are pausing Facebook ads only until the end of July, a one-month “sacrifice” that’s less than meets the eye. No brand that I’ve seen has suggested a permanent end to social media ads. Furthermore, nearly all of these brands have seen weakening revenues and need to find cuts to keep earnings robust. A temporary “furlough” of Facebook ads offers a good way to hang on to more of their funds.

As to whether a one-month pause hurts Facebook, as long as there are politicians in election season, there will be a tremendous revenue stream. Besides, Facebook makes most of its money off small, local businesses, not large advertisers. (...)

Not only is the strategy behind the boycott dubious, so is the solution it proposes. The idea seems to be that Facebook should actively intervene to make its platform less hostile, removing hate, bigotry, racism, misinformation, and violence. As a private platform, Facebook can in theory engage in whatever moderation it wishes. The problem is really the company’s dominance: It looks like censorship to those thrown off because Facebook holds such power over communications. This affects the manageability of the platform too: Facebook is simply too big to moderate, and its algorithmic efforts have failed.

The answer that can actually deal with these platforms is, of course, to break up Facebook, but also to ban targeted advertising. Changing Facebook’s surveillance-based business model would end the incentive toward mass data collection, return the specialness of unique audiences cultivated by publishers, and limit the click-bait dynamic that exists to hook users and scrape their personal information. The answer is certainly not to “pause” advertising until Facebook comes up with a minimally tolerable fig leaf that advertisers can wave around and declare victory.

This attempt to come up with a plausible narrative of progress, rather than rooting out structural failings, comprises a familiar tactic from those holding power. It’s why the Facebook boycott is a microcosm of the bid to resolve a month of protests over racism with distractions.

I don’t know about you, but I didn’t see the death of George Floyd as an opportunity to at long last give Black actors the opportunity to voice characters on long-running cartoons. Politics and culture have become intertwined, no doubt, but this virtue signaling mimics the stances of advertisers in the Facebook boycott. Brands can strut around, express support, and take actions that fall rather short of being meaningful. It gives the impression that centuries of racism can be solved by HR directives and “White Fragility” book clubs. It’s what happens when a corporate giant throws a few bucks at charity or names a stadium “Climate Pledge Arena.” It attempts to wave away dissent without personal cost.

It’s interesting that large corporations see value in using their power as purchasers to force changes, something their own customers might want to note for the future. And seeing Mark Zuckerberg in the crosshairs of a capital strike has a delightful quality to it. But let’s be clear: This is a cosmetic PR move from a corporate sector looking for simple, performative solutions to deep-seated persecution. Multinationals are trying to buy off protesters with empty symbols of solidarity and diversity training seminars. People are in the streets over far more than that.

It’s interesting that large corporations see value in using their power as purchasers to force changes, something their own customers might want to note for the future. And seeing Mark Zuckerberg in the crosshairs of a capital strike has a delightful quality to it. But let’s be clear: This is a cosmetic PR move from a corporate sector looking for simple, performative solutions to deep-seated persecution. Multinationals are trying to buy off protesters with empty symbols of solidarity and diversity training seminars. People are in the streets over far more than that.It’s very unclear whether this advertising boycott represents anything close to a sacrifice for advertisers. First off, most of the brands are pausing Facebook ads only until the end of July, a one-month “sacrifice” that’s less than meets the eye. No brand that I’ve seen has suggested a permanent end to social media ads. Furthermore, nearly all of these brands have seen weakening revenues and need to find cuts to keep earnings robust. A temporary “furlough” of Facebook ads offers a good way to hang on to more of their funds.

As to whether a one-month pause hurts Facebook, as long as there are politicians in election season, there will be a tremendous revenue stream. Besides, Facebook makes most of its money off small, local businesses, not large advertisers. (...)

Not only is the strategy behind the boycott dubious, so is the solution it proposes. The idea seems to be that Facebook should actively intervene to make its platform less hostile, removing hate, bigotry, racism, misinformation, and violence. As a private platform, Facebook can in theory engage in whatever moderation it wishes. The problem is really the company’s dominance: It looks like censorship to those thrown off because Facebook holds such power over communications. This affects the manageability of the platform too: Facebook is simply too big to moderate, and its algorithmic efforts have failed.

The answer that can actually deal with these platforms is, of course, to break up Facebook, but also to ban targeted advertising. Changing Facebook’s surveillance-based business model would end the incentive toward mass data collection, return the specialness of unique audiences cultivated by publishers, and limit the click-bait dynamic that exists to hook users and scrape their personal information. The answer is certainly not to “pause” advertising until Facebook comes up with a minimally tolerable fig leaf that advertisers can wave around and declare victory.

This attempt to come up with a plausible narrative of progress, rather than rooting out structural failings, comprises a familiar tactic from those holding power. It’s why the Facebook boycott is a microcosm of the bid to resolve a month of protests over racism with distractions.

I don’t know about you, but I didn’t see the death of George Floyd as an opportunity to at long last give Black actors the opportunity to voice characters on long-running cartoons. Politics and culture have become intertwined, no doubt, but this virtue signaling mimics the stances of advertisers in the Facebook boycott. Brands can strut around, express support, and take actions that fall rather short of being meaningful. It gives the impression that centuries of racism can be solved by HR directives and “White Fragility” book clubs. It’s what happens when a corporate giant throws a few bucks at charity or names a stadium “Climate Pledge Arena.” It attempts to wave away dissent without personal cost.

by David Dayen, The American Prospect | Read more:

Image: Nam Y. Huh/AP

Friday, July 3, 2020

Seattle's CHOP Went Out With a Bang and a Whimper

The fiery Seattle protests were Mark Anthony’s baptism into protest activism. He had been on the streets for barely a week when on June 8, the 32-year-old former brand ambassador and tour guide for Boeing headed to Capitol Hill. “I drove the entire way with some very choice words for the police,” he said. “I was disappointed when I got here, and they were gone.”

Anthony, who became a leader in the CHOP, said, “One of our white allies grabbed the first tent” — founding the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone that night.

The early vibe was like a festival. “It was a cross between Burning Man and Coachella,” one visitor said. Just as historic protests after Floyd’s death served as a release valve for deep rage against racist policing and relief from months of pandemic lockdown, the CHAZ was a flowering of hope that drew thousands in a season of death. (Organizers later changed the name to CHOP, saying that they were not seeking autonomy and to keep the focus on Black Lives Matter.)

Artists painted an enormous Black Lives Matter street mural that popped with life. DJs hosted late-night dance parties. Documentaries such as “Paris is Burning” and “13th” were screened outdoors. Native American drumming circles cohabited with meditation sessions. Plots of black earth sprouted leafy greens and placards honoring Black historical figures. A “No Cop Co-op” handed out toothpaste, toilet paper, and other supplies while the Riot Kitchen and Feed the Movement dished out free “vegetable kimchi tofu ‘pastrami’ reuben wraps and gochujang beef fried rice.” Families picnicked, social influencers livestreamed, and general assemblies and teach-ins were held regularly.

Artists painted an enormous Black Lives Matter street mural that popped with life. DJs hosted late-night dance parties. Documentaries such as “Paris is Burning” and “13th” were screened outdoors. Native American drumming circles cohabited with meditation sessions. Plots of black earth sprouted leafy greens and placards honoring Black historical figures. A “No Cop Co-op” handed out toothpaste, toilet paper, and other supplies while the Riot Kitchen and Feed the Movement dished out free “vegetable kimchi tofu ‘pastrami’ reuben wraps and gochujang beef fried rice.” Families picnicked, social influencers livestreamed, and general assemblies and teach-ins were held regularly.

The miniature society that sprang up was a legacy of a raft of occupation protests over the past years, Occupy Wall Street, Occupy Sandy, and Occupy ICE, in particular. These movements espoused principles of self-organization and mutual aid, where activists learned how to rapidly set up housing, health care, kitchens, education, child care, free stores, and tech support.

“CHOP had a very positive energy and people were taking care of each other. It was like Occupy on steroids,” said Michael, a member of the now-disbanded security team known as Sentinels, who asked that his last name not be used.

Yet the Occupy movements foundered on a broken society and the individuals it produced. One veteran organizer involved in New York’s Occupy movements, who asked not to be named, said, “Occupy is outside the authority of existing institutions. It’s a magnet for people who are needy and even pushy, abusive, and exploitive.”

Similar problems dogged the CHOP. Slate, another Sentinel who did not give a last name, said one self-appointed security person “pulled handguns on and maced people.”

“Tourists” drew considerable ire. “We had people flying in from all over because they thought it was a lawless place, a festival, anything goes,” said Anthony, the CHOP activist. “We made the DJs stop at midnight. We are separating the people here to protest from the people who came to party.”

A party was one draw; others came simply in search of a place. Homeless Seattleites, whose population has grown in recent years, poured into the CHOP. “Of course they are going to come to CHOP,” said Michael. “They got food, a free store, a safe place to sleep and hang out, and there is hope.” On top of that, he said, “Free thinkers do drugs, so there’s going to be people doing drugs. There’s going to be a market, so people will fight over it.” He speculated the drug trade attracted local gangs.

By the end of June, with families and tourists having disappeared because of the violence, the park looked like the end stage of many Occupy camps, with scores of people living in tents. “It’s not a protest,” said Hunt, the CHOP activist. “It’s a damn homeless encampment.” (...)

Despite differences with Occupy, the CHOP faltered for similar reasons. Movements that start online may capture the imagination with slogans like “We Are the 99%” or “Follow Black Leadership,” but they are too flimsy to bridge deep historical divisions. The all-are-welcome, open organizing form, meanwhile, is too shallow to allow for politics and too prone to manipulation. One observer described the general assemblies as more meandering speak-outs than disciplined strategy sessions.

“CHOP is like if Twitter were an actual place. It’s full of different ideologies, perspectives, and pains, and everyone thinks they are right and no one wants to be a follower,” said Slate. “I would hear the term ‘Black leadership’ 15 times a day, and no one knew who they were. There wasn’t a group with shared ideas and leadership.”

Hunt, for his part, is angry. “Greed drowned out the protests,” he said. “Everyone is fighting to be a leader because they want to be in the meeting with the mayor and say, ‘Defund the police and fund my organization.’ We didn’t come out here because nonprofits aren’t being funded. We came out here because cops are killing Black people.”

by Arun Gupta, The Intercept | Read more:

Image: David Ryder/Getty Images

Anthony, who became a leader in the CHOP, said, “One of our white allies grabbed the first tent” — founding the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone that night.

The early vibe was like a festival. “It was a cross between Burning Man and Coachella,” one visitor said. Just as historic protests after Floyd’s death served as a release valve for deep rage against racist policing and relief from months of pandemic lockdown, the CHAZ was a flowering of hope that drew thousands in a season of death. (Organizers later changed the name to CHOP, saying that they were not seeking autonomy and to keep the focus on Black Lives Matter.)

Artists painted an enormous Black Lives Matter street mural that popped with life. DJs hosted late-night dance parties. Documentaries such as “Paris is Burning” and “13th” were screened outdoors. Native American drumming circles cohabited with meditation sessions. Plots of black earth sprouted leafy greens and placards honoring Black historical figures. A “No Cop Co-op” handed out toothpaste, toilet paper, and other supplies while the Riot Kitchen and Feed the Movement dished out free “vegetable kimchi tofu ‘pastrami’ reuben wraps and gochujang beef fried rice.” Families picnicked, social influencers livestreamed, and general assemblies and teach-ins were held regularly.

Artists painted an enormous Black Lives Matter street mural that popped with life. DJs hosted late-night dance parties. Documentaries such as “Paris is Burning” and “13th” were screened outdoors. Native American drumming circles cohabited with meditation sessions. Plots of black earth sprouted leafy greens and placards honoring Black historical figures. A “No Cop Co-op” handed out toothpaste, toilet paper, and other supplies while the Riot Kitchen and Feed the Movement dished out free “vegetable kimchi tofu ‘pastrami’ reuben wraps and gochujang beef fried rice.” Families picnicked, social influencers livestreamed, and general assemblies and teach-ins were held regularly.The miniature society that sprang up was a legacy of a raft of occupation protests over the past years, Occupy Wall Street, Occupy Sandy, and Occupy ICE, in particular. These movements espoused principles of self-organization and mutual aid, where activists learned how to rapidly set up housing, health care, kitchens, education, child care, free stores, and tech support.

“CHOP had a very positive energy and people were taking care of each other. It was like Occupy on steroids,” said Michael, a member of the now-disbanded security team known as Sentinels, who asked that his last name not be used.

Yet the Occupy movements foundered on a broken society and the individuals it produced. One veteran organizer involved in New York’s Occupy movements, who asked not to be named, said, “Occupy is outside the authority of existing institutions. It’s a magnet for people who are needy and even pushy, abusive, and exploitive.”

Similar problems dogged the CHOP. Slate, another Sentinel who did not give a last name, said one self-appointed security person “pulled handguns on and maced people.”

“Tourists” drew considerable ire. “We had people flying in from all over because they thought it was a lawless place, a festival, anything goes,” said Anthony, the CHOP activist. “We made the DJs stop at midnight. We are separating the people here to protest from the people who came to party.”

A party was one draw; others came simply in search of a place. Homeless Seattleites, whose population has grown in recent years, poured into the CHOP. “Of course they are going to come to CHOP,” said Michael. “They got food, a free store, a safe place to sleep and hang out, and there is hope.” On top of that, he said, “Free thinkers do drugs, so there’s going to be people doing drugs. There’s going to be a market, so people will fight over it.” He speculated the drug trade attracted local gangs.

By the end of June, with families and tourists having disappeared because of the violence, the park looked like the end stage of many Occupy camps, with scores of people living in tents. “It’s not a protest,” said Hunt, the CHOP activist. “It’s a damn homeless encampment.” (...)

Despite differences with Occupy, the CHOP faltered for similar reasons. Movements that start online may capture the imagination with slogans like “We Are the 99%” or “Follow Black Leadership,” but they are too flimsy to bridge deep historical divisions. The all-are-welcome, open organizing form, meanwhile, is too shallow to allow for politics and too prone to manipulation. One observer described the general assemblies as more meandering speak-outs than disciplined strategy sessions.

“CHOP is like if Twitter were an actual place. It’s full of different ideologies, perspectives, and pains, and everyone thinks they are right and no one wants to be a follower,” said Slate. “I would hear the term ‘Black leadership’ 15 times a day, and no one knew who they were. There wasn’t a group with shared ideas and leadership.”

Hunt, for his part, is angry. “Greed drowned out the protests,” he said. “Everyone is fighting to be a leader because they want to be in the meeting with the mayor and say, ‘Defund the police and fund my organization.’ We didn’t come out here because nonprofits aren’t being funded. We came out here because cops are killing Black people.”

by Arun Gupta, The Intercept | Read more:

Image: David Ryder/Getty Images

Thursday, July 2, 2020

Battle Over Masks Rages in Texas

We don't live in a communist country!': battle over masks rages in Texas (The Guardian)

Image: Sergio Flores/Getty Images

[ed. Your choice, my body?]

Why Americans Are Having an Emotional Reaction to Masks

While Americans still have not adopted mask-wearing as a general norm, we’re wearing masks more than ever before. Mask-wearing is mandated in California, and in many counties masks are near-universal in public spaces. So I have started wondering: Does wearing a mask change our social behavior and our emotional inclinations? And if mask-wearing does indeed change the fabric of our interactions, is that one reason why the masks are not more popular in the U.S.?

When no one can see our countenances, we may behave differently. One study found that children wearing Halloween masks were more likely to break the rules and take more candy. The anonymity conferred by masks may be making it easier for protestors to knock down so many statues.

And indeed, people have long used masks to achieve a kind of plausible deniability. At Carnival festivities around the world people wear masks, and this seems to encourage greater revelry, drunkenness, and lewd behavior, traits also associated with masked balls. The mask creates another persona. You can act a little more outrageously, knowing that your town or village, a few days later, will regard that as “a different you.”

And indeed, people have long used masks to achieve a kind of plausible deniability. At Carnival festivities around the world people wear masks, and this seems to encourage greater revelry, drunkenness, and lewd behavior, traits also associated with masked balls. The mask creates another persona. You can act a little more outrageously, knowing that your town or village, a few days later, will regard that as “a different you.”

If we look to popular culture, mask-wearing is again associated with a kind of transgression. Batman, Robin and the Lone Ranger wear masks, not just to keep their true identities a secret, but to enable their “ordinary selves” to step into these larger-than-life roles.

But if we examine mask-wearing in the context of Covid-19, a different picture emerges. The mask is now a symbol of a particular kind of conformity, and a ritual of collective responsibility and discipline against the virus. The masks themselves might encourage this norm adherence by boosting the sense of group membership among the wearers.

The public health benefits of mask-wearing far exceed the social costs, but still if we want mask-wearing to be a stable norm we may need to protect against or at least recognize some of its secondary consequences, including the disorientations that masks can produce. Because mask-wearing norms seem weakest in many of the most open societies, such as the United States and United Kingdom, perhaps it is time to come to terms how masks rewrite how we react and respond to each other.

If nothing else, our smiles cannot be seen under our masks, and that makes social interactions feel more hostile and alienating, and it may lower immediate levels of trust in casual interactions. There are plenty of negative, hostile claims about masks circulating, to the point of seeming crazy, but rather than just mocking them perhaps we need to recognize what has long been called “the paranoid style in American politics.” If we admit that mask-wearing has a psychologically strange side, we might do better than simply to lecture the miscreants about their failings.

Just ask yourself a simple question: If someone tells you there is a new movie or TV show out, and everyone in the drama is wearing masks, do you tend to think that’s a feel-good romantic comedy, or a scary movie? In essence, we are asking Americans to live in that scenario, but not quite giving them the psychological armor to do so successfully.

When no one can see our countenances, we may behave differently. One study found that children wearing Halloween masks were more likely to break the rules and take more candy. The anonymity conferred by masks may be making it easier for protestors to knock down so many statues.

And indeed, people have long used masks to achieve a kind of plausible deniability. At Carnival festivities around the world people wear masks, and this seems to encourage greater revelry, drunkenness, and lewd behavior, traits also associated with masked balls. The mask creates another persona. You can act a little more outrageously, knowing that your town or village, a few days later, will regard that as “a different you.”

And indeed, people have long used masks to achieve a kind of plausible deniability. At Carnival festivities around the world people wear masks, and this seems to encourage greater revelry, drunkenness, and lewd behavior, traits also associated with masked balls. The mask creates another persona. You can act a little more outrageously, knowing that your town or village, a few days later, will regard that as “a different you.”If we look to popular culture, mask-wearing is again associated with a kind of transgression. Batman, Robin and the Lone Ranger wear masks, not just to keep their true identities a secret, but to enable their “ordinary selves” to step into these larger-than-life roles.

But if we examine mask-wearing in the context of Covid-19, a different picture emerges. The mask is now a symbol of a particular kind of conformity, and a ritual of collective responsibility and discipline against the virus. The masks themselves might encourage this norm adherence by boosting the sense of group membership among the wearers.

The public health benefits of mask-wearing far exceed the social costs, but still if we want mask-wearing to be a stable norm we may need to protect against or at least recognize some of its secondary consequences, including the disorientations that masks can produce. Because mask-wearing norms seem weakest in many of the most open societies, such as the United States and United Kingdom, perhaps it is time to come to terms how masks rewrite how we react and respond to each other.

If nothing else, our smiles cannot be seen under our masks, and that makes social interactions feel more hostile and alienating, and it may lower immediate levels of trust in casual interactions. There are plenty of negative, hostile claims about masks circulating, to the point of seeming crazy, but rather than just mocking them perhaps we need to recognize what has long been called “the paranoid style in American politics.” If we admit that mask-wearing has a psychologically strange side, we might do better than simply to lecture the miscreants about their failings.

Just ask yourself a simple question: If someone tells you there is a new movie or TV show out, and everyone in the drama is wearing masks, do you tend to think that’s a feel-good romantic comedy, or a scary movie? In essence, we are asking Americans to live in that scenario, but not quite giving them the psychological armor to do so successfully.

by Tyler Cowan, Bloomberg | Read more:

Image: Mark Makela/Getty ImagesThe End of Retirement

On Thanksgiving Day of 2010, Linda May sat alone in a trailer in New River, Arizona. At sixty, the silver-haired grandmother lacked electricity and running water. She couldn’t find work. Her unemployment benefits had run out, and her daughter’s family, with whom she had lived for many years while holding a series of low-wage jobs, had recently downsized to a smaller apartment. There wasn’t enough room to move back in with them.

“I’m going to drink all the booze. I’m going to turn on the propane. I’m going to pass out and that’ll be it,” she told herself. “And if I wake up, I’m going to light a cigarette and blow us all to hell.”

Her two small dogs were staring at her. May hesitated — could she really envision blowing them up as well? That wasn’t an option. So instead she accepted an invitation to a friend’s house for Thanksgiving dinner.

A couple of years later, May found herself close to the edge again. She was working as a Home Depot cashier for $10.50 an hour, which barely paid for her $600-a-month trailer in Lake Elsinore, California. She wondered, not for the first time, how anybody could afford to grow old. She had held many jobs in her life — building inspector, general contractor, flooring-store owner, insurance executive, cocktail waitress — but none had brought even a modicum of lasting financial security. “Never managed to get myself a pension,” said May, who wears bifocals with rose-colored plastic frames and reveals deep laugh lines when she smiles, which is often. She knew she would soon be eligible for Social Security benefits, but at $499 her monthly checks would not even cover the rent.

A couple of years later, May found herself close to the edge again. She was working as a Home Depot cashier for $10.50 an hour, which barely paid for her $600-a-month trailer in Lake Elsinore, California. She wondered, not for the first time, how anybody could afford to grow old. She had held many jobs in her life — building inspector, general contractor, flooring-store owner, insurance executive, cocktail waitress — but none had brought even a modicum of lasting financial security. “Never managed to get myself a pension,” said May, who wears bifocals with rose-colored plastic frames and reveals deep laugh lines when she smiles, which is often. She knew she would soon be eligible for Social Security benefits, but at $499 her monthly checks would not even cover the rent.

Soon after, though, May discovered the philosophy (and the extensive website) of a former Safeway clerk from Alaska named Bob Wells. In 1995, Wells had divorced, gone broke, and moved into a van. As he mastered the transient-survival arts — including “stealth parking” tactics to evade police and tricks for installing solar panels on vehicles — he shared them online. According to Wells, some “vandwellers” subsisted on $500 a month or less, a sum that made immediate sense to May. “If they could do it,” she thought, “I’m sure I could.”

She began to save up for the right vehicle. Then came a windfall: a temporary job at a Veterans Affairs hospital removing signage and repairing walls. The pay was fifty dollars an hour. Within a couple of months, May had accumulated enough cash to buy a 1994 Eldorado motor home with teal and black stripes she’d seen advertised on Craigslist. With only 29,000 miles on its odometer, the twenty-eight-foot RV should have been worth $17,000. But it smelled musty and had a broken generator and a hole in the shower, and a recent collision with a telephone pole had left a football-size crater in the loft above the cab, which had been patched with a smear of caulk that looked like dried toothpaste.

May got the RV for $4,000, then spent another $1,200 to replace the rotted tires. In June, she drove to her first seasonal job, at a campground near Yosemite National Park. For $8.50 an hour plus a place to park the Eldorado, May registered visitors, collected camping fees, and scrubbed toilets.

By late summer, smoke from the Rim wildfire was thickening the air and it was time to move on. May said her goodbyes and drove north. In mid-September, she arrived in Fernley, Nevada, where Amazon runs a warehouse so immense that its workers use the names of neighboring states to navigate its vast interior, calling the western half Nevada and the eastern half Utah. May now joined the company’s CamperForce: a graying labor corps consisting entirely of RV dwellers, many in their sixties or seventies, who work during the peak shopping season that starts in October and ends just before Christmas. She was hired for $12.25 an hour plus overtime to shelve inbound freight. But before her shifts actually began, she went through orientation sessions to acclimate herself to ten-hour workdays spent roaming the concrete-slab floor — a process Amazon refers to as “work hardening.”

“I was in construction and I cocktail-waitressed, which was harder work than construction,” May recalled. “What would I be worried about?”

Aging isn’t what it used to be. In an era of disappearing pensions, wage stagnation, and widespread foreclosures, Americans are working longer and leaning more heavily than ever on Social Security, a program designed to supplement (rather than fully fund) retirement. For many, surviving the golden years now requires creative lifestyle adjustments. And for those riding the economy’s outermost edge, adaptation may now mean giving up what full-time RV dwellers call “stick houses” to hit the road and seek work.

May is a member of that tribe. Many of her peers describe themselves as retired, even if they are obliged to keep working well into their seventies or eighties. They call themselves workampers, travelers, nomads, and gypsies, while history-minded commentators have labeled them the Okies of the Great Recession. More bluntly, they are geriatric migrant labor, meeting demands for seasonal work in an increasingly fragmented, temp-driven marketplace. And whatever you call them, they’re part of a demographic that in the past several years has grown with alarming speed: downwardly mobile older Americans.

“We’re facing the first-ever reversal in retirement security in modern U.S. history,” Monique Morrissey of the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, D.C., told me. “Starting with the younger baby boomers, each successive generation is now doing worse than previous generations in terms of their ability to retire without seeing a drop in living standards.”

That means no rest for the aging. Nearly 7.7 million Americans sixty-five and older were still employed last year, up 60 percent from a decade earlier. And while 71 percent of Americans aged fifty to sixty-five envision retirement as “a time of leisure,” according to a recent AARP survey, only 17 percent anticipate that they won’t work at all in their later years.

Of course, some older laborers remain in the workforce to stay busy and socially engaged. But most lack the luxury of choice — and since many of the regular jobs eliminated since 2008 will never come back, the seasonal work available to RV dwellers becomes even more tempting. There’s a national circuit extending from coast to coast and up into Canada, a labor market whose hundreds of employers post classified ads on websites with names like Workers on Wheels and Workamper News. As compensation, some offer only a version of bed and board — a place to park, with hookups for water, electricity, and sewage — while others pay an hourly wage.

Depending on the time of year, these geriatric migrants may be summoned to roadside stalls selling Christmas trees, Halloween pumpkins, or Fourth of July fireworks. They’re sought to pick raspberries in Vermont, apples in Washington, and blueberries in Kentucky. They give tours at fish hatcheries, take tickets at NASCAR races, and guard gates at Texas oil fields.1 They maintain hundreds of campgrounds and trailer parks from the Grand Canyon to Niagara Falls, recruited by private concessionaires along with the U.S. Forest Service and the Army Corps of Engineers. They staff many of the nation’s prime tourist traps, from Dolly Parton’s Dollywood theme park in Tennessee to Wall Drug, the kitschy roadside mall in South Dakota with its eighty-foot-long concrete brontosaurus and animatronic singing cowboys. (...)

Of all the programs seeking workampers, the largest and most rapidly expanding is Amazon’s CamperForce. It began as an experiment in 2008, when a handful of RV dwellers were hired for the pre-Christmas rush at the company’s warehouse in Coffeyville, Kansas. Pleased with the results, executives branded the program, gave it a logo — the black silhouette of an RV in motion, bearing the company’s smile insignia — and expanded it to warehouses in Campbellsville, Kentucky, and Fernley, Nevada. Over the past two years, Amazon has also begun hiring veteran CamperForce members to train workers at new distribution centers in Tracy, California; Murfreesboro, Tennessee; and Robbinsville, New Jersey. The company doesn’t publicly disclose the program’s size, but in January, when I asked a manager in an Amazon recruiting booth in Arizona, she estimated the number at 2,000 workers.

Workampers are plug-and-play labor, the epitome of convenience for employers in search of seasonal staffing. They appear where and when they are needed. They bring their own homes, transforming trailer parks into ephemeral company towns that empty out once the jobs are gone. They aren’t around long enough to unionize. On jobs that are physically difficult, many are too tired even to socialize after their shifts.

They also demand little in the way of benefits or protections. On the contrary, among the more than fifty such laborers I interviewed, most expressed appreciation for whatever semblance of stability their short-term jobs offered.

“I’m going to drink all the booze. I’m going to turn on the propane. I’m going to pass out and that’ll be it,” she told herself. “And if I wake up, I’m going to light a cigarette and blow us all to hell.”

Her two small dogs were staring at her. May hesitated — could she really envision blowing them up as well? That wasn’t an option. So instead she accepted an invitation to a friend’s house for Thanksgiving dinner.

A couple of years later, May found herself close to the edge again. She was working as a Home Depot cashier for $10.50 an hour, which barely paid for her $600-a-month trailer in Lake Elsinore, California. She wondered, not for the first time, how anybody could afford to grow old. She had held many jobs in her life — building inspector, general contractor, flooring-store owner, insurance executive, cocktail waitress — but none had brought even a modicum of lasting financial security. “Never managed to get myself a pension,” said May, who wears bifocals with rose-colored plastic frames and reveals deep laugh lines when she smiles, which is often. She knew she would soon be eligible for Social Security benefits, but at $499 her monthly checks would not even cover the rent.

A couple of years later, May found herself close to the edge again. She was working as a Home Depot cashier for $10.50 an hour, which barely paid for her $600-a-month trailer in Lake Elsinore, California. She wondered, not for the first time, how anybody could afford to grow old. She had held many jobs in her life — building inspector, general contractor, flooring-store owner, insurance executive, cocktail waitress — but none had brought even a modicum of lasting financial security. “Never managed to get myself a pension,” said May, who wears bifocals with rose-colored plastic frames and reveals deep laugh lines when she smiles, which is often. She knew she would soon be eligible for Social Security benefits, but at $499 her monthly checks would not even cover the rent.Soon after, though, May discovered the philosophy (and the extensive website) of a former Safeway clerk from Alaska named Bob Wells. In 1995, Wells had divorced, gone broke, and moved into a van. As he mastered the transient-survival arts — including “stealth parking” tactics to evade police and tricks for installing solar panels on vehicles — he shared them online. According to Wells, some “vandwellers” subsisted on $500 a month or less, a sum that made immediate sense to May. “If they could do it,” she thought, “I’m sure I could.”

She began to save up for the right vehicle. Then came a windfall: a temporary job at a Veterans Affairs hospital removing signage and repairing walls. The pay was fifty dollars an hour. Within a couple of months, May had accumulated enough cash to buy a 1994 Eldorado motor home with teal and black stripes she’d seen advertised on Craigslist. With only 29,000 miles on its odometer, the twenty-eight-foot RV should have been worth $17,000. But it smelled musty and had a broken generator and a hole in the shower, and a recent collision with a telephone pole had left a football-size crater in the loft above the cab, which had been patched with a smear of caulk that looked like dried toothpaste.

May got the RV for $4,000, then spent another $1,200 to replace the rotted tires. In June, she drove to her first seasonal job, at a campground near Yosemite National Park. For $8.50 an hour plus a place to park the Eldorado, May registered visitors, collected camping fees, and scrubbed toilets.

By late summer, smoke from the Rim wildfire was thickening the air and it was time to move on. May said her goodbyes and drove north. In mid-September, she arrived in Fernley, Nevada, where Amazon runs a warehouse so immense that its workers use the names of neighboring states to navigate its vast interior, calling the western half Nevada and the eastern half Utah. May now joined the company’s CamperForce: a graying labor corps consisting entirely of RV dwellers, many in their sixties or seventies, who work during the peak shopping season that starts in October and ends just before Christmas. She was hired for $12.25 an hour plus overtime to shelve inbound freight. But before her shifts actually began, she went through orientation sessions to acclimate herself to ten-hour workdays spent roaming the concrete-slab floor — a process Amazon refers to as “work hardening.”

“I was in construction and I cocktail-waitressed, which was harder work than construction,” May recalled. “What would I be worried about?”

Aging isn’t what it used to be. In an era of disappearing pensions, wage stagnation, and widespread foreclosures, Americans are working longer and leaning more heavily than ever on Social Security, a program designed to supplement (rather than fully fund) retirement. For many, surviving the golden years now requires creative lifestyle adjustments. And for those riding the economy’s outermost edge, adaptation may now mean giving up what full-time RV dwellers call “stick houses” to hit the road and seek work.

May is a member of that tribe. Many of her peers describe themselves as retired, even if they are obliged to keep working well into their seventies or eighties. They call themselves workampers, travelers, nomads, and gypsies, while history-minded commentators have labeled them the Okies of the Great Recession. More bluntly, they are geriatric migrant labor, meeting demands for seasonal work in an increasingly fragmented, temp-driven marketplace. And whatever you call them, they’re part of a demographic that in the past several years has grown with alarming speed: downwardly mobile older Americans.

“We’re facing the first-ever reversal in retirement security in modern U.S. history,” Monique Morrissey of the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, D.C., told me. “Starting with the younger baby boomers, each successive generation is now doing worse than previous generations in terms of their ability to retire without seeing a drop in living standards.”

That means no rest for the aging. Nearly 7.7 million Americans sixty-five and older were still employed last year, up 60 percent from a decade earlier. And while 71 percent of Americans aged fifty to sixty-five envision retirement as “a time of leisure,” according to a recent AARP survey, only 17 percent anticipate that they won’t work at all in their later years.

Of course, some older laborers remain in the workforce to stay busy and socially engaged. But most lack the luxury of choice — and since many of the regular jobs eliminated since 2008 will never come back, the seasonal work available to RV dwellers becomes even more tempting. There’s a national circuit extending from coast to coast and up into Canada, a labor market whose hundreds of employers post classified ads on websites with names like Workers on Wheels and Workamper News. As compensation, some offer only a version of bed and board — a place to park, with hookups for water, electricity, and sewage — while others pay an hourly wage.

Depending on the time of year, these geriatric migrants may be summoned to roadside stalls selling Christmas trees, Halloween pumpkins, or Fourth of July fireworks. They’re sought to pick raspberries in Vermont, apples in Washington, and blueberries in Kentucky. They give tours at fish hatcheries, take tickets at NASCAR races, and guard gates at Texas oil fields.1 They maintain hundreds of campgrounds and trailer parks from the Grand Canyon to Niagara Falls, recruited by private concessionaires along with the U.S. Forest Service and the Army Corps of Engineers. They staff many of the nation’s prime tourist traps, from Dolly Parton’s Dollywood theme park in Tennessee to Wall Drug, the kitschy roadside mall in South Dakota with its eighty-foot-long concrete brontosaurus and animatronic singing cowboys. (...)

Of all the programs seeking workampers, the largest and most rapidly expanding is Amazon’s CamperForce. It began as an experiment in 2008, when a handful of RV dwellers were hired for the pre-Christmas rush at the company’s warehouse in Coffeyville, Kansas. Pleased with the results, executives branded the program, gave it a logo — the black silhouette of an RV in motion, bearing the company’s smile insignia — and expanded it to warehouses in Campbellsville, Kentucky, and Fernley, Nevada. Over the past two years, Amazon has also begun hiring veteran CamperForce members to train workers at new distribution centers in Tracy, California; Murfreesboro, Tennessee; and Robbinsville, New Jersey. The company doesn’t publicly disclose the program’s size, but in January, when I asked a manager in an Amazon recruiting booth in Arizona, she estimated the number at 2,000 workers.

Workampers are plug-and-play labor, the epitome of convenience for employers in search of seasonal staffing. They appear where and when they are needed. They bring their own homes, transforming trailer parks into ephemeral company towns that empty out once the jobs are gone. They aren’t around long enough to unionize. On jobs that are physically difficult, many are too tired even to socialize after their shifts.

They also demand little in the way of benefits or protections. On the contrary, among the more than fifty such laborers I interviewed, most expressed appreciation for whatever semblance of stability their short-term jobs offered.

by Jessica Bruder, Harper's | Read more:

Image: Max WhittakerWednesday, July 1, 2020

Coronavirus Brings American Decline Out in the Open

[ed. We're No. 1 Go USA!]

The U.S.’s decline started with little things that people got used to. Americans drove past empty construction sites and didn’t even think about why the workers weren’t working, then wondered why roads and buildings took so long to finish. They got used to avoiding hospitals because of the unpredictable and enormous bills they’d receive. They paid 6% real-estate commissions, never realizing that Australians were paying 2%. They grumbled about high taxes and high health-insurance premiums and potholed roads, but rarely imagined what it would be like to live in a system that worked better.

When writers speak of American decline, they’re usually talking about international power -- the rise of China and the waning of U.S. hegemony and moral authority. To most Americans, those are distant and abstract things that have little or no impact on their daily lives. But the decline in the general effectiveness of U.S. institutions will impose increasing costs and burdens on Americans. And if it eventually leads to a general loss of investor confidence in the country, the damage could be much greater.

The most immediate cost of U.S. decline -- and the most vivid demonstration -- comes from the country’s disastrous response to the coronavirus pandemic. Leadership failures were pervasive and catastrophic at every level -- the president, agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and the Food and Drug Administration, and state and local leaders all fumbled the response to the greatest health threat in a century. As a result, the U.S. is suffering a horrific surge of infections in states such as Arizona, Texas and Florida while states that were battered early on are still struggling. Countries such as Italy that are legendary for government dysfunction and were hit hard by the virus have crushed the curve of infection, while the U.S. just set a daily record for case growth and shows no sign of slowing down. (...)

But the consequences of U.S. decline will far outlast coronavirus. With its high housing costs, poor infrastructure and transit, endemic gun violence, police brutality and bitter political and racial divisions, the U.S. will be a less appealing place for high-skilled workers to live. That means companies will find other countries in Europe, Asia and elsewhere a more attractive destination for investment, robbing the U.S. of jobs, depressing wages and draining away the local spending that powers the service economy. That in turn will exacerbate some of the worst trends of U.S. decline -- less tax money means even more urban decay as infrastructure, education and social-welfare programs are forced to make big cuts. Anti-immigration policies will throw away the country’s most important source of skilled labor and weaken a university system already under tremendous pressure from state budget cuts.

Almost every systematic economic advantage possessed by the U.S. is under threat. Unless there’s a huge push to turn things around -- to bring back immigrants, sustain research universities, make housing cheaper, lower infrastructure costs, reform the police and restore competence to the civil service -- the result could be decades of stagnating or even declining living standards.

And a biggest danger might come later. The U.S. has long enjoyed a so-called exorbitant privilege as the financial center of the world, with the dollar as the lynchpin of the global financial system. That means the U.S. has been able to borrow money cheaply, and Americans have been able to sustain their lifestyles through cheap imports. But if enough investors -- foreign and domestic -- lose confidence in the U.S.’s general effectiveness as a country, that advantage will vanish.

by Noah Smith, Bloomberg | Read more:

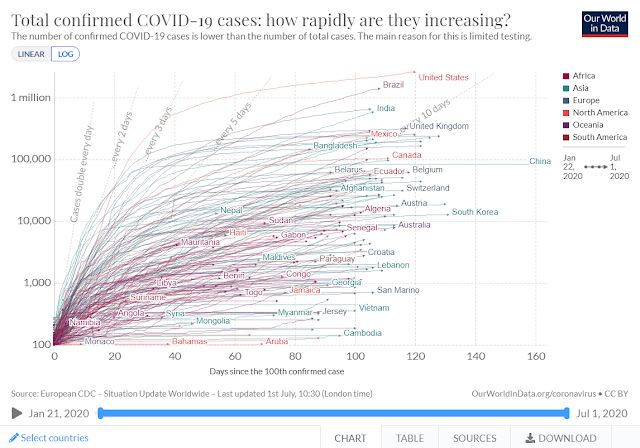

Image: CDC, Situation Update Worldwide[ed. It's Bloomberg, so you might expect the author to forget to mention corporate/financial malfeasance and decades of tax avoidance (leading to extraordinary wealth inequality) as contributing factors, if not sources, of many of America's problems. In my view, it all started with Reagan and the relentless push to privatize or cut government services. See also: America has almost 800 billionaires, a record high (Recode).]

Tuesday, June 30, 2020

Seattle Pride (Revisted)

Repost: Seattle Pride (photos from 2015)

Images: markk

[ed. Life used to be so much fun when we actually had something called Culture. See also: Virtual Seattle Pride Fest Has Businesses Yearning for Years Past (Bloomberg).]

Private Gain, Public Loss

Putting public services in private hands is bad economics. Worse, it undermines our bonds as a political community

Barbara and Mary are happily married. Barbara wants to buy Mary a new ring for her birthday. The problem is that Barbara knows nothing about jewellery. Fortunately, their neighbour John is an expert. Barbara can ask John to select the ring, or she could invest the time and energy to learn about gemstones and alloys herself, and choose the ring on the basis of her own judgment. What should Barbara do?

One answer might be that, given John’s expertise, Barbara should delegate the power to select the jewellery to John. After all, he’ll probably make a better choice. Another equally compelling answer, though, is that Mary might care not only about the beauty and quality of the chosen ring, but also about who selected it. Mary might want Barbara to engage in the task of buying the ring, even if Barbara’s choice is ultimately inferior to John’s.

This little fable illustrates something that’s often missed in debates about a very different subject: privatisation. The project of selling state or public assets to be owned or run by private businesses has always been controversial. What characterises the controversy, though, is that both advocates and opponents tend to cast it in instrumental terms. That is, the identity of the body or entity doesn’t matter in and of itself; what matters is whether or not they achieve a good outcome or do a better job. Whether or not something should be privatised, then, appears to depend on who is more likely to make the right decisions for the right ends. What’s more, the mainstream conversation about privatisation assumes that civil servants and public institutions are mere tools, more or less, for making these decisions.

This little fable illustrates something that’s often missed in debates about a very different subject: privatisation. The project of selling state or public assets to be owned or run by private businesses has always been controversial. What characterises the controversy, though, is that both advocates and opponents tend to cast it in instrumental terms. That is, the identity of the body or entity doesn’t matter in and of itself; what matters is whether or not they achieve a good outcome or do a better job. Whether or not something should be privatised, then, appears to depend on who is more likely to make the right decisions for the right ends. What’s more, the mainstream conversation about privatisation assumes that civil servants and public institutions are mere tools, more or less, for making these decisions.

But that view is shortsighted. We don’t just care about what the decision is and whether a decision is right, just, efficient or good. We also care about who makes the decision. As the story of Barbara, Mary and John shows, we often feel strongly not just about which ring gets chosen, but also about who chooses the ring. Similarly, a public institution differs from a private one not only in the quality or justness of the outcome, but also because decisions made by a public body are attributable to citizens – as a matter of fact, they are the decisions of the citizens. Only a public agent can speak in our name. So mass privatisation doesn’t simply shift decision-making away from public institutions to unaccountable, private entities; it also undermines shared civic responsibility and the very existence of collective political will.

At the level of the state, the equivalent of allowing John to choose Mary’s ring could theoretically be a nation in which all parks, public museums, prisons, forests, health services and other institutions are private. In such a world, citizens couldn’t really affect how these services operate. What’s more, they’d be unlikely to feel responsible for these institutions – to sense that these institutions are theirs. They might have grudges or complaints but, ultimately, the power of making decisions would rest with the private owner of the service or institution. In this scenario, people would lose their very sense of belonging to a political unit, whose future they should control through collective effort. (...)

When private actors take over state functions, they’re authorised to act for reasons beyond the public interest – to make money for themselves, for example, or to improve the value of their stock for shareholders. Within the boundaries set by law, private entities don’t need to defer to the state. Indeed, privatisation presupposes that companies and other private entities are empowered to act in their own interests, within the terms of their contract, to perform a service for citizens. In the absence of this power there would be no difference between private and public entities. By its very nature, then, privatisation deprives the public of control. By privatising the provision of a good or a service, the state distances itself from the activity, or, at least, from the decisions of a company (or another private entity) acting within the limits set by law. In contrast, by acting as a unified public – by using civil servants to perform certain tasks – citizens remain responsible, and are more likely to regard the acts of the political community as their own.

On this view, privatisation undermines an important dimension of our moral practices: the taking of responsibility on the part of citizens. In particular, privatisation downplays the political dimension of responsibility by absolving citizens of their duty to be involved in important choices. This doesn’t rely on a particular view of human psychology, but stems from the fact that being involved in political decisions is part of what facilitates collective responsibility. Spheres of activity that are privatised are excluded from this collective undertaking and are hidden away behind a corporate veil; they become the exclusive business of the private entity tasked with making the decision.

by Alon Harel, Aeon | Read more:

Image: John Moore/Getty

Barbara and Mary are happily married. Barbara wants to buy Mary a new ring for her birthday. The problem is that Barbara knows nothing about jewellery. Fortunately, their neighbour John is an expert. Barbara can ask John to select the ring, or she could invest the time and energy to learn about gemstones and alloys herself, and choose the ring on the basis of her own judgment. What should Barbara do?

One answer might be that, given John’s expertise, Barbara should delegate the power to select the jewellery to John. After all, he’ll probably make a better choice. Another equally compelling answer, though, is that Mary might care not only about the beauty and quality of the chosen ring, but also about who selected it. Mary might want Barbara to engage in the task of buying the ring, even if Barbara’s choice is ultimately inferior to John’s.

This little fable illustrates something that’s often missed in debates about a very different subject: privatisation. The project of selling state or public assets to be owned or run by private businesses has always been controversial. What characterises the controversy, though, is that both advocates and opponents tend to cast it in instrumental terms. That is, the identity of the body or entity doesn’t matter in and of itself; what matters is whether or not they achieve a good outcome or do a better job. Whether or not something should be privatised, then, appears to depend on who is more likely to make the right decisions for the right ends. What’s more, the mainstream conversation about privatisation assumes that civil servants and public institutions are mere tools, more or less, for making these decisions.

This little fable illustrates something that’s often missed in debates about a very different subject: privatisation. The project of selling state or public assets to be owned or run by private businesses has always been controversial. What characterises the controversy, though, is that both advocates and opponents tend to cast it in instrumental terms. That is, the identity of the body or entity doesn’t matter in and of itself; what matters is whether or not they achieve a good outcome or do a better job. Whether or not something should be privatised, then, appears to depend on who is more likely to make the right decisions for the right ends. What’s more, the mainstream conversation about privatisation assumes that civil servants and public institutions are mere tools, more or less, for making these decisions.But that view is shortsighted. We don’t just care about what the decision is and whether a decision is right, just, efficient or good. We also care about who makes the decision. As the story of Barbara, Mary and John shows, we often feel strongly not just about which ring gets chosen, but also about who chooses the ring. Similarly, a public institution differs from a private one not only in the quality or justness of the outcome, but also because decisions made by a public body are attributable to citizens – as a matter of fact, they are the decisions of the citizens. Only a public agent can speak in our name. So mass privatisation doesn’t simply shift decision-making away from public institutions to unaccountable, private entities; it also undermines shared civic responsibility and the very existence of collective political will.