Thursday, July 23, 2020

Jacob Collier

Nostalgia Reimagined

He was still too young to know that the heart’s memory eliminates the bad and magnifies the good, and that thanks to this artifice we manage to endure the burden of the past. But when he stood at the railing of the ship and saw the white promontory of the colonial district again, the motionless buzzards on the roofs, the washing of the poor hung out to dry on the balconies, only then did he understand to what extent he had been an easy victim to the charitable deceptions of nostalgia.The other day I caught myself reminiscing about high school with a kind of sadness and longing that can only be described as nostalgia. I felt imbued with a sense of wanting to go back in time and re-experience my classroom, the gym, the long hallways. Such bouts of nostalgia are all too common, but this case was striking because there is something I know for sure: I hated high school. I used to have nightmares, right before graduation, about having to redo it all, and would wake up in sweat and agony. I would never, ever like to go back to high school. So why did I feel nostalgia about a period I wouldn’t like to relive? The answer, as it turns out, requires we rethink our traditional idea of nostalgia.

– From Love in the Time of Cholera (1985) by Gabriel García Márquez

Coined by the Swiss physician Johannes Hofer in 1688, ‘nostalgia’ referred to a medical condition – homesickness – characterised by an incapacitating longing for one’s motherland. Hofer favoured the term because it combined two essential features of the illness: the desire to return home (nostos) and the pain (algos) of being unable to do so. Nostalgia’s symptomatology was imprecise – it included rumination, melancholia, insomnia, anxiety and lack of appetite – and was thought to affect primarily soldiers and sailors. Physicians also disagreed about its cause. Hofer thought that nostalgia was caused by nerve vibrations where traces of ideas of the motherland ‘still cling’, whereas others, noticing that it was found predominantly among Swiss soldiers fighting at lower altitudes, proposed instead that nostalgia was caused by changes in atmospheric pressure, or eardrum damage from the clanging of Swiss cowbells. Once nostalgia was identified among soldiers from various nationalities, the idea that it was geographically specific was abandoned.

Coined by the Swiss physician Johannes Hofer in 1688, ‘nostalgia’ referred to a medical condition – homesickness – characterised by an incapacitating longing for one’s motherland. Hofer favoured the term because it combined two essential features of the illness: the desire to return home (nostos) and the pain (algos) of being unable to do so. Nostalgia’s symptomatology was imprecise – it included rumination, melancholia, insomnia, anxiety and lack of appetite – and was thought to affect primarily soldiers and sailors. Physicians also disagreed about its cause. Hofer thought that nostalgia was caused by nerve vibrations where traces of ideas of the motherland ‘still cling’, whereas others, noticing that it was found predominantly among Swiss soldiers fighting at lower altitudes, proposed instead that nostalgia was caused by changes in atmospheric pressure, or eardrum damage from the clanging of Swiss cowbells. Once nostalgia was identified among soldiers from various nationalities, the idea that it was geographically specific was abandoned.By the early 20th century, nostalgia was considered a psychiatric rather than neurological illness – a variant of melancholia. Within the psychoanalytic tradition, the object of nostalgia – ie, what the nostalgic state is about – was dissociated from its cause. Nostalgia can manifest as a desire to return home, but – according to psychoanalysts – it is actually caused by the traumatic experience of being removed from one’s mother at birth. This account began to be questioned in the 1940s, with nostalgia once again linked to homesickness. ‘Home’ was now interpreted more broadly to include not only concrete places, such as a childhood town, but also abstract ones, such as past experiences or bygone moments. While disagreements lingered, by the second part of the 20th century, nostalgia began to be characterised as involving three components. The first was cognitive: nostalgia involves the retrieval of autobiographical memories. The second, affective: nostalgia is considered a debilitating, negatively valenced emotion. And third, conative: nostalgia comprises a desire to return to one’s homeland. As I’ll argue, however, this tripartite characterisation of nostalgia is likely wrong.

by Felipe De Brigard, Aeon | Read more:

Image: Winslow Homer

Wednesday, July 22, 2020

Experimental Blood Test Detects Cancer up to Four Years before Symptoms Appear

For years scientists have sought to create the ultimate cancer-screening test—one that can reliably detect a malignancy early, before tumor cells spread and when treatments are more effective. A new method reported today in Nature Communications brings researchers a step closer to that goal. By using a blood test, the international team was able to diagnose cancer long before symptoms appeared in nearly all the people it tested who went on to develop cancer.

“What we showed is: up to four years before these people walk into the hospital, there are already signatures in their blood that show they have cancer,” says Kun Zhang, a bioengineer at the University of California, San Diego, and a co-author of the study. “That’s never been done before.”

Past efforts to develop blood tests for cancer typically involved researchers collecting blood samples from people already diagnosed with the disease. They would then see if they could accurately detect malignant cells in those samples, usually by looking at genetic mutations, DNA methylation (chemical alterations to DNA) or specific blood proteins. “The best you can prove is whether your method is as good at detecting cancer as existing methods,” Zhang says. “You can never prove it’s better.”

Past efforts to develop blood tests for cancer typically involved researchers collecting blood samples from people already diagnosed with the disease. They would then see if they could accurately detect malignant cells in those samples, usually by looking at genetic mutations, DNA methylation (chemical alterations to DNA) or specific blood proteins. “The best you can prove is whether your method is as good at detecting cancer as existing methods,” Zhang says. “You can never prove it’s better.”

In contrast, Zhang and his colleagues began collecting samples from people before they had any signs that they had cancer. In 2007 the researchers began recruiting more than 123,000 healthy individuals in Taizhou, China, to undergo annual health checks—an effort that required building a specialized warehouse to store the more than 1.6 million samples they eventually accrued. Around 1,000 participants developed cancer over the next 10 years.

Zhang and his colleagues focused on developing a test for five of the most common types of cancer: stomach, esophageal, colorectal, lung and liver malignancies. The test they developed, called PanSeer, detects methylation patterns in which a chemical group is added to DNA to alter genetic activity. Past studies have shown that abnormal methylation can signal various types of cancer, including pancreatic and colon cancer.

The PanSeer test works by isolating DNA from a blood sample and measuring DNA methylation at 500 locations previously identified as having the greatest chance of signaling the presence of cancer. A machine-learning algorithm compiles the findings into a single score that indicates a person’s likelihood of having the disease. The researchers tested blood samples from 191 participants who eventually developed cancer, paired with the same number of matching healthy individuals. They were able to detect cancer up to four years before symptoms appeared with roughly 90 percent accuracy and a 5 percent false-positive rate.

by Rachel Nuwer, Scientific American | Read more:

Image: Getty

[ed. I wonder what happened to all the enthusiasm for AI, CRISPR, Big Data, etc. to solve all our problems. And in latest Covid19 news): The Pandemic May Very Well Last Another Year or More (vaccine production - Bloomberg); and Rapid, Cheap, Less Accurate Coronavirus Testing Has A Place, Scientists Say (NPR).]

“What we showed is: up to four years before these people walk into the hospital, there are already signatures in their blood that show they have cancer,” says Kun Zhang, a bioengineer at the University of California, San Diego, and a co-author of the study. “That’s never been done before.”

Past efforts to develop blood tests for cancer typically involved researchers collecting blood samples from people already diagnosed with the disease. They would then see if they could accurately detect malignant cells in those samples, usually by looking at genetic mutations, DNA methylation (chemical alterations to DNA) or specific blood proteins. “The best you can prove is whether your method is as good at detecting cancer as existing methods,” Zhang says. “You can never prove it’s better.”

Past efforts to develop blood tests for cancer typically involved researchers collecting blood samples from people already diagnosed with the disease. They would then see if they could accurately detect malignant cells in those samples, usually by looking at genetic mutations, DNA methylation (chemical alterations to DNA) or specific blood proteins. “The best you can prove is whether your method is as good at detecting cancer as existing methods,” Zhang says. “You can never prove it’s better.”In contrast, Zhang and his colleagues began collecting samples from people before they had any signs that they had cancer. In 2007 the researchers began recruiting more than 123,000 healthy individuals in Taizhou, China, to undergo annual health checks—an effort that required building a specialized warehouse to store the more than 1.6 million samples they eventually accrued. Around 1,000 participants developed cancer over the next 10 years.

Zhang and his colleagues focused on developing a test for five of the most common types of cancer: stomach, esophageal, colorectal, lung and liver malignancies. The test they developed, called PanSeer, detects methylation patterns in which a chemical group is added to DNA to alter genetic activity. Past studies have shown that abnormal methylation can signal various types of cancer, including pancreatic and colon cancer.

The PanSeer test works by isolating DNA from a blood sample and measuring DNA methylation at 500 locations previously identified as having the greatest chance of signaling the presence of cancer. A machine-learning algorithm compiles the findings into a single score that indicates a person’s likelihood of having the disease. The researchers tested blood samples from 191 participants who eventually developed cancer, paired with the same number of matching healthy individuals. They were able to detect cancer up to four years before symptoms appeared with roughly 90 percent accuracy and a 5 percent false-positive rate.

by Rachel Nuwer, Scientific American | Read more:

Image: Getty

[ed. I wonder what happened to all the enthusiasm for AI, CRISPR, Big Data, etc. to solve all our problems. And in latest Covid19 news): The Pandemic May Very Well Last Another Year or More (vaccine production - Bloomberg); and Rapid, Cheap, Less Accurate Coronavirus Testing Has A Place, Scientists Say (NPR).]

What You Need To Know About The Battle of Portland

The city of Portland, Oregon is currently in the national spotlight after video evidence of federal agents driving rented vans and abducting activists went viral. This footage was taken in the early morning hours of July 15, and an Oregon Public Broadcasting article published on the 16th brought the matter out of the local social networks of Portland activists and on to the national stage.

As I write this, mainstream media personalities are beginning to parachute into Portland to cover what some have dubbed the “fascist takeover of Portland”. The word “Gestapo” is trending on Twitter.

The Beginning (...)

At a little before 11 p.m., several dozen protesters began to shatter the windows of the Justice Center. They entered the building, trashing the interior and lighting random fires inside. I watched all this happen from feet away, and it is my opinion that the destruction was unplanned, yet more or less inevitable — you could feel it in the mood of the crowd. The 3rd Precinct in Minneapolis had just burned: there was absolutely no way Portland wasn’t going to try to do the same thing.

Of course, the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) arrived very shortly thereafter. In one of the more gentlemanly moments of the entire uprising, they gave a warning to people who’d brought their families and dogs, urging them to leave. A sizable chunk of more moderate demonstrators went home. A thousand or more protesters ranked up, and began shouting at the police. At a little after midnight, the PPB launched the first of what would eventually be hundreds of tear gas grenades into the crowd.

The crowd scattered, pushed by police in several different directions at once. They split into several groups. One rampaged through a series of downtown banks, shattering windows and lighting fires as they ran from the cops. Another, larger group of demonstrators tore through the luxury shopping district, sacking the Apple Store, Louis Vuitton, H&M and, eventually, looting a Target. The rest of the night was a messy haze of gas, flash-bangs, and burning barricades.

The Portland Police have stated that more than a dozen riots took place over the last fifty days, but May 29th remains the only night that truly felt like the actual people of this city were rioting. (...)

The Edge of All-Out War

On July 4th, Portland’s thirty-ninth consecutive night of protests, more than a thousand people assembled in front of the Justice Center and Federal Courthouse downtown. They began launching dozens of commercial-grade fireworks into the concrete facades of both buildings, prompting a response from the police and federal agents inside both buildings.

What followed resembled nothing so much as a medieval siege. The windows of both government buildings had been covered in plywood weeks ago, after the first riots. Officers inside fired out through murder holes cut in the plywood, pumping rubber bullets, pepper balls and foam rounds into the crowd, while the crowd formed phalanxes of shield-bearers to protect the men and women launching fireworks back in response. Federal agents dumped tear gas into the street, but Portland’s frontline activists had long since lost their fear of gas. The feds and the police were eventually forced to sally out with batons to drive the crowd back.

I reported on the fighting in Mosul back in 2017, and what happened that night in the streets of Portland was, of course, not nearly as brutal or dangerous as actual combat. Yet it was about as close as you can get without using live ammunition. At times, dozens of flash-bangs and fireworks would detonate within feet of us over the course of a few minutes. My ears rang for days afterwards. My hands shook. I could not write for days. (...)

Perhaps this will change as the protests continue. But thus far, the only escalation seen recently has been the federal agents now roaming the streets of downtown Portland in rented vans, arresting activists seemingly at random. These men display no identification, no name tag or badge number or anything else that might be useful identifying them. That fact has rightly shocked Americans across the country, but at this point, it is nothing new to Portland protesters.

Portland Police have been hiding their names for weeks, instead using numbers that cannot be correlated to names by any means available to citizens. Members of multiple different law enforcement agencies, all with different rules of engagement from the PPB, have been policing demonstrations since the very beginning. As Tuck Woodstock, a local reporter, noted on Twitter:

“This is the natural escalation of the last 7 weeks. This is what has come of Portlanders protesting police brutality for 50 days: more bizarre acts of police brutality. Portlanders are risking everything every day. Please notice.”That is, in the end, what both the Portland press corps and the people out in the streets, protesting every night, seem to want from the rest of the United States. Please pay attention to the videos of officers ripping people’s face masks off to spray mace directly into their mouths. Please pay attention to the video of Donovan LaBella, blood gushing from his head, seizing on the ground. And, yes, please pay attention to the videos of men in full combat gear abducting activists off the street.

Pay attention, because it is my belief that all of this will not stay confined to Portland. Your city might be next.

by Robert Evans, Bellingcat | Read more:

Images: Mason Trinca for The New York Times

[ed. Wow. Total craziness (with videos). Federal intervention is doing nothing but inflame an already bad situation.]

Tuesday, July 21, 2020

New Psychedelic Research Sheds Light on Why Psilocybin-Containing Mushrooms Have Been Consumed for Centuries

A new study from the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine provides insight into the psychoactive effects that distinguish psilocybin from other hallucinogenic substances. The findings suggest that feelings of spiritual and/or psychological insight play an important role in the drug’s popularity.

The new study has been published in the journal Psychopharmacology.

“Recently there has been a renewal of interest in research with psychedelic drugs,” explained Roland R. Griffiths, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences who is the corresponding author of the new study.

“Studies from the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research and elsewhere suggest that psilocybin, a classic psychedelic drug, has significant potential for treating various psychiatric conditions such as depression and drug dependence disorders. This study sought to address a simple but somewhat perplexing question: Why do people use psilocybin?”

“Studies from the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research and elsewhere suggest that psilocybin, a classic psychedelic drug, has significant potential for treating various psychiatric conditions such as depression and drug dependence disorders. This study sought to address a simple but somewhat perplexing question: Why do people use psilocybin?”

“Psilocybin, in the form of hallucinogenic mushrooms, has been used for centuries for the psychoactive effects. Recent US survey studies show that lifetime psilocybin use is relatively modest and quite stable over a period of decades,” Griffiths explained.

“However, the National Institute on Drug Abuse does not consider psilocybin to be addictive because it does not cause uncontrollable drug seeking behavior, does not produce classic euphoria, does not produce a withdrawal syndrome, and does not activate brain mechanisms associated with classic drugs of abuse.”

In the double-blind study, 20 healthy participants with histories of hallucinogen use received doses of psilocybin, dextromethorphan (DXM), and a placebo during five experiment sessions. (...)

The researchers found that most of the participants reported wanting to take psilocybin again. But only 1 in 4 reported wanting to take DXM again.

“The study showed that several subjective features of the drug experience predicted participants’ desire to take psilocybin again: psychological insight, meaningfulness of the experience, increased awareness of beauty, positive social effects (e.g. empathy), positive mood (e.g. inner peace), amazement, and mystical-type effects,” Griffiths explained.

Nearly half of the participants rated their experience following the highest psilocybin dose to be among the top most meaningful and psychologically insightful of their lives.

“The study provides an answer to the puzzle for why psilocybin has been used by people for hundreds of years, yet it does not share any of the features used to define classic drugs of abuse. The answer seems to reside in the ability of psilocybin to produce unique changes in the human conscious experience that give rise to meaning, insight, the experience of beauty and mystical-type effects,” Griffiths said.

The new study has been published in the journal Psychopharmacology.

“Recently there has been a renewal of interest in research with psychedelic drugs,” explained Roland R. Griffiths, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences who is the corresponding author of the new study.

“Studies from the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research and elsewhere suggest that psilocybin, a classic psychedelic drug, has significant potential for treating various psychiatric conditions such as depression and drug dependence disorders. This study sought to address a simple but somewhat perplexing question: Why do people use psilocybin?”

“Studies from the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research and elsewhere suggest that psilocybin, a classic psychedelic drug, has significant potential for treating various psychiatric conditions such as depression and drug dependence disorders. This study sought to address a simple but somewhat perplexing question: Why do people use psilocybin?”“Psilocybin, in the form of hallucinogenic mushrooms, has been used for centuries for the psychoactive effects. Recent US survey studies show that lifetime psilocybin use is relatively modest and quite stable over a period of decades,” Griffiths explained.

“However, the National Institute on Drug Abuse does not consider psilocybin to be addictive because it does not cause uncontrollable drug seeking behavior, does not produce classic euphoria, does not produce a withdrawal syndrome, and does not activate brain mechanisms associated with classic drugs of abuse.”

In the double-blind study, 20 healthy participants with histories of hallucinogen use received doses of psilocybin, dextromethorphan (DXM), and a placebo during five experiment sessions. (...)

The researchers found that most of the participants reported wanting to take psilocybin again. But only 1 in 4 reported wanting to take DXM again.

“The study showed that several subjective features of the drug experience predicted participants’ desire to take psilocybin again: psychological insight, meaningfulness of the experience, increased awareness of beauty, positive social effects (e.g. empathy), positive mood (e.g. inner peace), amazement, and mystical-type effects,” Griffiths explained.

Nearly half of the participants rated their experience following the highest psilocybin dose to be among the top most meaningful and psychologically insightful of their lives.

“The study provides an answer to the puzzle for why psilocybin has been used by people for hundreds of years, yet it does not share any of the features used to define classic drugs of abuse. The answer seems to reside in the ability of psilocybin to produce unique changes in the human conscious experience that give rise to meaning, insight, the experience of beauty and mystical-type effects,” Griffiths said.

by Eric W. Dolan, PsyPost | Read more:

Image: uncredited

Monday, July 20, 2020

Breaking Into The Close-Knit World Of Country Music, While Keeping Distant

The early experiments in COVID-19-era concerts have been watched closely, because the stakes are clearly high on both sides of the coin: the possibility of salvaging lost musical livelihoods has to be balanced against any potential exposure risks for all involved. So far, country acts seem to have outpaced those in other genres when it comes to experimenting with live show layouts, from those that separate pods of attendees in vehicles or outdoor suites to those that let audience members cram in shoulder to shoulder, just like the good, old, pre-pandemic days.

But concerts aren't the only career-furthering events that the Nashville industry has been going without. Another type of gathering routinely happens out of public view, its function to promote new acts and new music to industry gatekeepers, tastemakers and professional peers. Often, a small bar or venue will be rented out for these boozy, schmoozy shindigs. It's about getting face time, as opposed to FaceTime, so artists will work the room making friendly conversation. If they're new to the game, they're likely to have a publicist by their side providing guidance and making introductions.Of course, lockdown brought those rituals to a halt too, but attempts to safely (and resourcefully) replace them have begun.

Country success tends to require staunch participation in the Nashville community. That's one of the many reasons that Lil Nas X's winking, cowboy-burlesquing, hip-hop virality seemed so out of step with country music's establishment, at least initially — he pulled it off without them.

Country success tends to require staunch participation in the Nashville community. That's one of the many reasons that Lil Nas X's winking, cowboy-burlesquing, hip-hop virality seemed so out of step with country music's establishment, at least initially — he pulled it off without them.

Today's centralized country music industry is the result of once geographically, culturally and stylistically disparate and distinct threads being woven into a consolidated, popular (and artificially whitewashed) format, with its business and creative infrastructure and towering historical narrative staunchly headquartered in Nashville. It's not easy to launch and sustain a recording and touring career in this world without winning over some of its major players, securing the approval, opportunities, institutional support and media coverage they have to give. Performing know-how matters, but so does being eager and personable.

So the events where up-close access happens do serve a real purpose: The albums that were released rather than postponed just after the nation went into quarantine — which included established names at pivotal points in their careers, like Ashley McBryde, Sam Hunt, Kelsea Ballerini and Maddie & Tae, and promising country-pop newbie Ingrid Andress — likely forfeited some of the recognition they might have gotten if plans to promote them in person hadn't been canceled out of necessity. It's no wonder that record label, management and publicity staff are seeking innovative stopgaps.

Just over a week before the release of the debut country single by Shy Carter — a biracial, Memphis-bred, singer-rapper who had a decade of pop-R&B, hip-hop and country songwriting credits and guest spots under his belt, but was new to the Warner Nashville roster — a label rep emailed with the offer of an "At-Home Artist Visit." The proposed scenario involved Carter giving some sort of brief performance on a flatbed truck that would be parked in front of my residence. I was too curious, about both the extravagance of the scheme and the act it was meant to introduce, to decline.

As it turned out, what rolled up in front of my house around lunchtime that Friday wasn't an industrial hauler at all — just a shiny, silver pickup.

A guy who identified himself as Carter's brother hopped out the passenger side first, followed by Carter himself, both of them extending greetings. I asked Carter how many stops he'd already covered on his mini-tour that day. This was only his second, he reported brightly, implying the specialness of the visit.

The driver walked to the back of the truck, lowered the tailgate and slid a small portable PA onto it, while Carter's sole live accompanist swung his legs over the side of the truck bed and perched there, balancing an acoustic guitar on his lap. The remaining two members of the entourage, one of them a publicist, emerged from a second vehicle, keeping a respectable distance on the sidewalk. A few neighbors walked over and spread out in the yard to watch.

We were all wearing fabric face masks, but Carter removed his to sing into a microphone, revealing a luminous smile. He was a seasoned and charismatic enough entertainer to seem entirely unfazed by the awkwardness of serenading me from my sidewalk.

by Jewly Hight, NPR | Read more:

Image: Jewly Hight

But concerts aren't the only career-furthering events that the Nashville industry has been going without. Another type of gathering routinely happens out of public view, its function to promote new acts and new music to industry gatekeepers, tastemakers and professional peers. Often, a small bar or venue will be rented out for these boozy, schmoozy shindigs. It's about getting face time, as opposed to FaceTime, so artists will work the room making friendly conversation. If they're new to the game, they're likely to have a publicist by their side providing guidance and making introductions.Of course, lockdown brought those rituals to a halt too, but attempts to safely (and resourcefully) replace them have begun.

Country success tends to require staunch participation in the Nashville community. That's one of the many reasons that Lil Nas X's winking, cowboy-burlesquing, hip-hop virality seemed so out of step with country music's establishment, at least initially — he pulled it off without them.

Country success tends to require staunch participation in the Nashville community. That's one of the many reasons that Lil Nas X's winking, cowboy-burlesquing, hip-hop virality seemed so out of step with country music's establishment, at least initially — he pulled it off without them.Today's centralized country music industry is the result of once geographically, culturally and stylistically disparate and distinct threads being woven into a consolidated, popular (and artificially whitewashed) format, with its business and creative infrastructure and towering historical narrative staunchly headquartered in Nashville. It's not easy to launch and sustain a recording and touring career in this world without winning over some of its major players, securing the approval, opportunities, institutional support and media coverage they have to give. Performing know-how matters, but so does being eager and personable.

So the events where up-close access happens do serve a real purpose: The albums that were released rather than postponed just after the nation went into quarantine — which included established names at pivotal points in their careers, like Ashley McBryde, Sam Hunt, Kelsea Ballerini and Maddie & Tae, and promising country-pop newbie Ingrid Andress — likely forfeited some of the recognition they might have gotten if plans to promote them in person hadn't been canceled out of necessity. It's no wonder that record label, management and publicity staff are seeking innovative stopgaps.

Just over a week before the release of the debut country single by Shy Carter — a biracial, Memphis-bred, singer-rapper who had a decade of pop-R&B, hip-hop and country songwriting credits and guest spots under his belt, but was new to the Warner Nashville roster — a label rep emailed with the offer of an "At-Home Artist Visit." The proposed scenario involved Carter giving some sort of brief performance on a flatbed truck that would be parked in front of my residence. I was too curious, about both the extravagance of the scheme and the act it was meant to introduce, to decline.

As it turned out, what rolled up in front of my house around lunchtime that Friday wasn't an industrial hauler at all — just a shiny, silver pickup.

A guy who identified himself as Carter's brother hopped out the passenger side first, followed by Carter himself, both of them extending greetings. I asked Carter how many stops he'd already covered on his mini-tour that day. This was only his second, he reported brightly, implying the specialness of the visit.

The driver walked to the back of the truck, lowered the tailgate and slid a small portable PA onto it, while Carter's sole live accompanist swung his legs over the side of the truck bed and perched there, balancing an acoustic guitar on his lap. The remaining two members of the entourage, one of them a publicist, emerged from a second vehicle, keeping a respectable distance on the sidewalk. A few neighbors walked over and spread out in the yard to watch.

We were all wearing fabric face masks, but Carter removed his to sing into a microphone, revealing a luminous smile. He was a seasoned and charismatic enough entertainer to seem entirely unfazed by the awkwardness of serenading me from my sidewalk.

by Jewly Hight, NPR | Read more:

Image: Jewly Hight

Sunday, July 19, 2020

Portland Burns

Portland Police Union Burns in Latest Night of Protests in Portland (The Stranger)

Image: Mathieu Lewis-Roland

[ed. See also: Federal and Local Police Team Up in Aggressive Response to Day 50 of Portland Protests]

Strike With the Band

The union for the musicians of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, late this June, refused to sign a contract that would cut its unionized musicians’ income by some 20 percent. The musicians were, in turn, locked out by management, which meant facing months without pay or health care. In a Baltimore Sun article, orchestra members told of their fears about losing homes and caring for sick loved ones. Perhaps the most striking interview in the report comes from a twenty-seven-year-old violinist who had done everything right: she was talented and worked intensively; after college she rose through the ranks from the second to the first violin section, finally landing her dream job with a union symphony. But before that, she went to the right schools, Oberlin Conservatory and the Manhattan School of Music, at a cost of over $100,000 in student loan debt. This was debt she was determined to pay off by the time she was forty, if she continued her frugal lifestyle, living with a roommate near the concert hall. And now, here she was walking the picket line with her railroaded colleagues, who had also done everything right.

The world of classical music is neither noble nor fair, though its reputation says otherwise. This is partly because to be classically trained means being regarded among the highest caliber of skilled musicians. Those who achieve such heights are capable of playing the most complex, technically difficult music on equally complex instruments that take decades to master. The prestige that comes with this mastery is, of course, heavily dependent on rankings—orchestra rankings, seating charts, a general fetishization of skill and dedication. And classical music itself is considered the highest echelon of institutional art music, its practice spanning centuries, its history a tapestry of colorful personalities and political upheaval. Like fine art and classical literature, it is considered a high-water mark for culture, a pastime enjoyed largely by the rich, the old, and the snobby. But classical music can be other things, too: transcendental, lush, heartbreakingly emotional. Nothing captures pure rapturous anguish like the third movement of the Shostakovich Violin Concerto; the profound unrest of unrequited love can be found in the see-sawing feverishness and piercing cries of Janàcek’s Second String Quartet; and one still comes out of the 23rd Mozart Piano Concerto or a Mahler symphony in a swirling, euphoric trance.

These are musical experiences that can change the life of a young person. It can give them reason to believe in the power of art above all else, and it can encourage a desire to participate in this art at all costs. I was one of these young people. After seeing Vanessa-Mae on the Disney Channel at the age of three, I begged my parents to let me play the violin. They waited until I was four and had the motor skills to at least use a pair of scissors, and finally granted my wish. They rented my first violin, tiny and horrible sounding, from Johnson String Instruments. Growing up in rural North Carolina, I took violin lessons from a woman who lived in a trailer. She had a stern voice and wore muddy boots. I switched to private lessons from one of the local school teachers, before, in my senior year of high school, commuting to the nearest city to take precious few lessons with one of the musicians from the local symphony. I can’t remember a time in my life when I didn’t play the violin. It was the backbone of my upbringing, my adolescence, my young adulthood. My formative human experiences, heartbreaks, desires, triumphs, and joys all revolved around playing the goddamn violin.

These are musical experiences that can change the life of a young person. It can give them reason to believe in the power of art above all else, and it can encourage a desire to participate in this art at all costs. I was one of these young people. After seeing Vanessa-Mae on the Disney Channel at the age of three, I begged my parents to let me play the violin. They waited until I was four and had the motor skills to at least use a pair of scissors, and finally granted my wish. They rented my first violin, tiny and horrible sounding, from Johnson String Instruments. Growing up in rural North Carolina, I took violin lessons from a woman who lived in a trailer. She had a stern voice and wore muddy boots. I switched to private lessons from one of the local school teachers, before, in my senior year of high school, commuting to the nearest city to take precious few lessons with one of the musicians from the local symphony. I can’t remember a time in my life when I didn’t play the violin. It was the backbone of my upbringing, my adolescence, my young adulthood. My formative human experiences, heartbreaks, desires, triumphs, and joys all revolved around playing the goddamn violin.

Meanwhile, I was discouraged from pursuing a number of different careers—botany, architecture, creative writing. But I was never, somehow, discouraged from pursuing a life in classical music. Growing up in a small Southern town, I was a shark in a little pond, better than my peers because I had a head start. Everyone thought I was talented, including myself, as I nabbed first chair after first chair. With every victory, the belief that the world was just and fair, and that the talented and hardworking would inherit it, became more and more cemented in my child-soul. When I was in high school, I decided I wanted to be a composer more than a violinist. I wrote my first pieces, little violin ditties, during my sophomore year. Pirated notation software expanded the ensembles to string and even chamber orchestra. I begged my parents to let me attend a pre-college summer program for composers at the Cleveland Institute of Music.

I should have thought twice about the career choice I had impulsively made at the age of seventeen when my parents explained they could only afford to send me to an in-state school instead of an out-of-state, high-end conservatory. My unshaken worldview relented, telling me that if I worked hard, I would succeed no matter which school I attended. I enrolled in the University of North Carolina at Greensboro in the fall of 2012. Frankly, I’m glad I went there and graduated debt free instead of going to an expensive conservatory, where the crushing of my dreams would have been far more expensive.

Elective Epiphanies

In music school, you have time to do two things: make music and drink. I threw myself into doing both. I spent the $5,000 inheritance left to me by my grandfather, the same inheritance my sister used for a down payment on her house, to go to expensive summer festivals where you get to spend an hour a week with a composer whose name looks good on your resume. This is where I began to see the writing on the walls, when I met other musicians: those born into artistic families in big cities, ingrained into classical music culture at a young age; those who matriculated expensive and prestigious music schools; those attending their third festival of the summer. Meanwhile, I worked almost every night at a minimum wage job in the school recording studio to make ends meet; and I turned down a career-changing unpaid internship in one of the most important new music institutions in the composer mecca of Brooklyn because neither I nor my parents could afford for me to live in New York for a summer.

One day, around the beginning of my junior year of college, it occurred to me that I wasn’t going to make it. I had already developed carpal tunnel and tendonitis from years of improper violin technique taught to me by my rural music teachers. I was out of money to go to festivals, and I had no way of making lasting, important connections in a field where who you know matters more than anything else. I had no serious job prospects, nor any hope for job prospects. At work one night, the falseness of the “work hard and you will succeed” ethic washed over me: the truth was the music world was a two-tiered system, and I was in the second chair. Hungover, in the comfort of a dark recording booth, I began to cry. Few things are as life altering as realizing your preferred life is unalterably a fucked impossibility.

I needed a way out. I threw myself into my work at the recording studio, thanks to the generous help of my boss and mentor, who frequently let me skip class in his office in order to do so. I memorized signal chains, did an independent study on piano microphone techniques, studied circuit diagrams, and built synthesizers on breadboards. I got a paid internship at a speaker company, applied to a single graduate program in audio science at the Peabody Institute, got in on scholarship, and still managed to accrue $44,000 of student loan debt, graduating embittered. In a twist of fate, my blog went viral, and I became a full-time writer. The end. That’s the end of the story of how I devoted my life to a singular cause for twenty years and then didn’t do it anymore. I picked up the violin a few months ago, after two years of carpal tunnel recovery, and found myself unable to play pieces I had mastered in the sixth grade.

The myth of meritocracy had swallowed my early life. It also swallowed the small lifetime of the young violinist on lockout at the Baltimore Symphony. And it swallowed the small lifetimes of the dozens of people I spoke to when writing this article, all of whom asked to remain anonymous out of fear of retribution in this tiny, vindictive world.

Classical music is cruel not because there are winners and losers, first chairs and second chairs, but because it lies about the fact that these winners and losers are chosen long before the first moment a young child picks up an instrument. It doesn’t matter if you study composition, devote years to an instrument, or simply have the desire to teach—either at the university level or in the public school system. If you come from a less-than-wealthy family, or from a place other than the wealthiest cities, the odds are stacked against you no matter how much you sacrifice, how hard you work, or, yes, how talented you are.

Vetted and Indebted

Despite its reputation as being a pastime of the rich and cultured elite, classical musicianship is better understood as a job, a shitty job, and the people who do that job are workers just as exploited as any Teamster. Classical music has a high rate of workplace injury, especially chronic pain and hearing loss. Many musicians don’t own their instruments, some of which can be as expensive as a new car. My high school orchestra teacher, who played in a regional symphony, was still paying off a viola that cost $20,000. Even the elite among players don’t own their instruments outright; many of these instruments, including Amati and Stradivari violins, are loaned by philanthropists as gifts. I had to rent violins from the same company for sixteen years before I had accrued enough credit to buy one outright at $7,000, right before I graduated from college. One percussionist I interviewed, who works as a middle school band teacher, told me: “As a percussionist, another point of privilege comes with equipment. To own everything we could ever need professionally is very costly, especially a marimba, vibraphone, and full set of timpani. So that’s another huge point of privilege when, for example, one of my middle school students . . . his parents bought him a marimba earlier in the year. Which is great for him, yet here I am with my master’s degree, and I definitely don’t own one yet. I probably won’t for a long time.”

[ed. See also: The Prodigy Complex: On Children in Classical Music]

The world of classical music is neither noble nor fair, though its reputation says otherwise. This is partly because to be classically trained means being regarded among the highest caliber of skilled musicians. Those who achieve such heights are capable of playing the most complex, technically difficult music on equally complex instruments that take decades to master. The prestige that comes with this mastery is, of course, heavily dependent on rankings—orchestra rankings, seating charts, a general fetishization of skill and dedication. And classical music itself is considered the highest echelon of institutional art music, its practice spanning centuries, its history a tapestry of colorful personalities and political upheaval. Like fine art and classical literature, it is considered a high-water mark for culture, a pastime enjoyed largely by the rich, the old, and the snobby. But classical music can be other things, too: transcendental, lush, heartbreakingly emotional. Nothing captures pure rapturous anguish like the third movement of the Shostakovich Violin Concerto; the profound unrest of unrequited love can be found in the see-sawing feverishness and piercing cries of Janàcek’s Second String Quartet; and one still comes out of the 23rd Mozart Piano Concerto or a Mahler symphony in a swirling, euphoric trance.

These are musical experiences that can change the life of a young person. It can give them reason to believe in the power of art above all else, and it can encourage a desire to participate in this art at all costs. I was one of these young people. After seeing Vanessa-Mae on the Disney Channel at the age of three, I begged my parents to let me play the violin. They waited until I was four and had the motor skills to at least use a pair of scissors, and finally granted my wish. They rented my first violin, tiny and horrible sounding, from Johnson String Instruments. Growing up in rural North Carolina, I took violin lessons from a woman who lived in a trailer. She had a stern voice and wore muddy boots. I switched to private lessons from one of the local school teachers, before, in my senior year of high school, commuting to the nearest city to take precious few lessons with one of the musicians from the local symphony. I can’t remember a time in my life when I didn’t play the violin. It was the backbone of my upbringing, my adolescence, my young adulthood. My formative human experiences, heartbreaks, desires, triumphs, and joys all revolved around playing the goddamn violin.

These are musical experiences that can change the life of a young person. It can give them reason to believe in the power of art above all else, and it can encourage a desire to participate in this art at all costs. I was one of these young people. After seeing Vanessa-Mae on the Disney Channel at the age of three, I begged my parents to let me play the violin. They waited until I was four and had the motor skills to at least use a pair of scissors, and finally granted my wish. They rented my first violin, tiny and horrible sounding, from Johnson String Instruments. Growing up in rural North Carolina, I took violin lessons from a woman who lived in a trailer. She had a stern voice and wore muddy boots. I switched to private lessons from one of the local school teachers, before, in my senior year of high school, commuting to the nearest city to take precious few lessons with one of the musicians from the local symphony. I can’t remember a time in my life when I didn’t play the violin. It was the backbone of my upbringing, my adolescence, my young adulthood. My formative human experiences, heartbreaks, desires, triumphs, and joys all revolved around playing the goddamn violin.Meanwhile, I was discouraged from pursuing a number of different careers—botany, architecture, creative writing. But I was never, somehow, discouraged from pursuing a life in classical music. Growing up in a small Southern town, I was a shark in a little pond, better than my peers because I had a head start. Everyone thought I was talented, including myself, as I nabbed first chair after first chair. With every victory, the belief that the world was just and fair, and that the talented and hardworking would inherit it, became more and more cemented in my child-soul. When I was in high school, I decided I wanted to be a composer more than a violinist. I wrote my first pieces, little violin ditties, during my sophomore year. Pirated notation software expanded the ensembles to string and even chamber orchestra. I begged my parents to let me attend a pre-college summer program for composers at the Cleveland Institute of Music.

I should have thought twice about the career choice I had impulsively made at the age of seventeen when my parents explained they could only afford to send me to an in-state school instead of an out-of-state, high-end conservatory. My unshaken worldview relented, telling me that if I worked hard, I would succeed no matter which school I attended. I enrolled in the University of North Carolina at Greensboro in the fall of 2012. Frankly, I’m glad I went there and graduated debt free instead of going to an expensive conservatory, where the crushing of my dreams would have been far more expensive.

Elective Epiphanies

In music school, you have time to do two things: make music and drink. I threw myself into doing both. I spent the $5,000 inheritance left to me by my grandfather, the same inheritance my sister used for a down payment on her house, to go to expensive summer festivals where you get to spend an hour a week with a composer whose name looks good on your resume. This is where I began to see the writing on the walls, when I met other musicians: those born into artistic families in big cities, ingrained into classical music culture at a young age; those who matriculated expensive and prestigious music schools; those attending their third festival of the summer. Meanwhile, I worked almost every night at a minimum wage job in the school recording studio to make ends meet; and I turned down a career-changing unpaid internship in one of the most important new music institutions in the composer mecca of Brooklyn because neither I nor my parents could afford for me to live in New York for a summer.

One day, around the beginning of my junior year of college, it occurred to me that I wasn’t going to make it. I had already developed carpal tunnel and tendonitis from years of improper violin technique taught to me by my rural music teachers. I was out of money to go to festivals, and I had no way of making lasting, important connections in a field where who you know matters more than anything else. I had no serious job prospects, nor any hope for job prospects. At work one night, the falseness of the “work hard and you will succeed” ethic washed over me: the truth was the music world was a two-tiered system, and I was in the second chair. Hungover, in the comfort of a dark recording booth, I began to cry. Few things are as life altering as realizing your preferred life is unalterably a fucked impossibility.

I needed a way out. I threw myself into my work at the recording studio, thanks to the generous help of my boss and mentor, who frequently let me skip class in his office in order to do so. I memorized signal chains, did an independent study on piano microphone techniques, studied circuit diagrams, and built synthesizers on breadboards. I got a paid internship at a speaker company, applied to a single graduate program in audio science at the Peabody Institute, got in on scholarship, and still managed to accrue $44,000 of student loan debt, graduating embittered. In a twist of fate, my blog went viral, and I became a full-time writer. The end. That’s the end of the story of how I devoted my life to a singular cause for twenty years and then didn’t do it anymore. I picked up the violin a few months ago, after two years of carpal tunnel recovery, and found myself unable to play pieces I had mastered in the sixth grade.

The myth of meritocracy had swallowed my early life. It also swallowed the small lifetime of the young violinist on lockout at the Baltimore Symphony. And it swallowed the small lifetimes of the dozens of people I spoke to when writing this article, all of whom asked to remain anonymous out of fear of retribution in this tiny, vindictive world.

Classical music is cruel not because there are winners and losers, first chairs and second chairs, but because it lies about the fact that these winners and losers are chosen long before the first moment a young child picks up an instrument. It doesn’t matter if you study composition, devote years to an instrument, or simply have the desire to teach—either at the university level or in the public school system. If you come from a less-than-wealthy family, or from a place other than the wealthiest cities, the odds are stacked against you no matter how much you sacrifice, how hard you work, or, yes, how talented you are.

Vetted and Indebted

Despite its reputation as being a pastime of the rich and cultured elite, classical musicianship is better understood as a job, a shitty job, and the people who do that job are workers just as exploited as any Teamster. Classical music has a high rate of workplace injury, especially chronic pain and hearing loss. Many musicians don’t own their instruments, some of which can be as expensive as a new car. My high school orchestra teacher, who played in a regional symphony, was still paying off a viola that cost $20,000. Even the elite among players don’t own their instruments outright; many of these instruments, including Amati and Stradivari violins, are loaned by philanthropists as gifts. I had to rent violins from the same company for sixteen years before I had accrued enough credit to buy one outright at $7,000, right before I graduated from college. One percussionist I interviewed, who works as a middle school band teacher, told me: “As a percussionist, another point of privilege comes with equipment. To own everything we could ever need professionally is very costly, especially a marimba, vibraphone, and full set of timpani. So that’s another huge point of privilege when, for example, one of my middle school students . . . his parents bought him a marimba earlier in the year. Which is great for him, yet here I am with my master’s degree, and I definitely don’t own one yet. I probably won’t for a long time.”

by Kate Wagner, The Baffler | Read more:

Image: Clemens Habicht[ed. See also: The Prodigy Complex: On Children in Classical Music]

In Absentia

Clementina doesn’t know who she is. She doesn’t know her nine children, her grandchildren, or the names of her mother and father. She doesn’t know where she lives, where she has lived, or where she is now. People she has never met tell her that they love her. They say they are her daughter or her son. They assure her they used to play cards together — make wine in the bodega across from her house and chorizo on the patio after the local matanzas (pig slaughters). But Clementina doesn’t trust these people; she doesn’t know what they are talking about.

She didn’t trust me either when I first met her seven years ago. I was at my girlfriend’s family home in Villaveta, a dusty hamlet of dilapidated houses in the hinterland of Castilla y León, Spain. We were preparing lunch for the whole family. Clementina sat at the head of the table next to me. She was hunched by her 93 years, and her skin was wrinkled like a date. “Who are you my boy? she asked, squinting through creamy cataracts.

I mumbled that I was her granddaughter’s boyfriend and that I was from Scotland. “Oh, darling, you’ve traveled a long way today,” she croaked. “You must be hungry.”

I mumbled that I was her granddaughter’s boyfriend and that I was from Scotland. “Oh, darling, you’ve traveled a long way today,” she croaked. “You must be hungry.”

Clementina looked away to ask one of her children something, but when she turned to me again, her brow crumpled. She felt for the contours of her face. She jolted her head back and forth: from her daughters and then back to me. But she found no answers. Then her hand, swollen like fresh ginger, seized my arm. “When are we leaving?” she whispered. “I don’t know these people.”

That was the first time I had met someone with dementia. I had never witnessed that type of fear or seen someone so threatened, by what, seconds before, had been familiar to them. Over the following years, I would return to the village with my girlfriend with relative regularity, and I watched as Clementina’s condition deteriorated. I saw how it weighed on the family.

When Clementina became frightened and refused to eat, when she had forgotten even her earliest memory, that’s when the family felt it most. I saw her daughters’ shoulders sink and her sons’ brows furrow; in fear and frustration.

Their mother’s decrepit frame warned of life’s fragility, or more precisely, its cruelty. Would this be their future in 20 years? Would they be the next to slurp on liquified meat and stare into the abyss? A somberness hung over the dinner table on those days. They all knew it, but talking meant facing too many complicated problems. There was grief, though no one had died.

I thought about this type of grief a lot over the following years; how it must take its toll — how it was possible to miss someone who was right there in front of you. And I thought about it more when my own grandmother died in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Clementina’s story was in no way similar to my grandmother’s. In many ways, they were complete opposites. But over the days and weeks that followed, as across the world, tragedies pixelated into statistics across TV screens, when people talked about death and infection rates like they were football scores, each helped me better understand the other.

by Matthew Bremner, Longreads | Read more:

Image: Getty

She didn’t trust me either when I first met her seven years ago. I was at my girlfriend’s family home in Villaveta, a dusty hamlet of dilapidated houses in the hinterland of Castilla y León, Spain. We were preparing lunch for the whole family. Clementina sat at the head of the table next to me. She was hunched by her 93 years, and her skin was wrinkled like a date. “Who are you my boy? she asked, squinting through creamy cataracts.

I mumbled that I was her granddaughter’s boyfriend and that I was from Scotland. “Oh, darling, you’ve traveled a long way today,” she croaked. “You must be hungry.”

I mumbled that I was her granddaughter’s boyfriend and that I was from Scotland. “Oh, darling, you’ve traveled a long way today,” she croaked. “You must be hungry.”Clementina looked away to ask one of her children something, but when she turned to me again, her brow crumpled. She felt for the contours of her face. She jolted her head back and forth: from her daughters and then back to me. But she found no answers. Then her hand, swollen like fresh ginger, seized my arm. “When are we leaving?” she whispered. “I don’t know these people.”

That was the first time I had met someone with dementia. I had never witnessed that type of fear or seen someone so threatened, by what, seconds before, had been familiar to them. Over the following years, I would return to the village with my girlfriend with relative regularity, and I watched as Clementina’s condition deteriorated. I saw how it weighed on the family.

When Clementina became frightened and refused to eat, when she had forgotten even her earliest memory, that’s when the family felt it most. I saw her daughters’ shoulders sink and her sons’ brows furrow; in fear and frustration.

Their mother’s decrepit frame warned of life’s fragility, or more precisely, its cruelty. Would this be their future in 20 years? Would they be the next to slurp on liquified meat and stare into the abyss? A somberness hung over the dinner table on those days. They all knew it, but talking meant facing too many complicated problems. There was grief, though no one had died.

I thought about this type of grief a lot over the following years; how it must take its toll — how it was possible to miss someone who was right there in front of you. And I thought about it more when my own grandmother died in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Clementina’s story was in no way similar to my grandmother’s. In many ways, they were complete opposites. But over the days and weeks that followed, as across the world, tragedies pixelated into statistics across TV screens, when people talked about death and infection rates like they were football scores, each helped me better understand the other.

by Matthew Bremner, Longreads | Read more:

Image: Getty

Saturday, July 18, 2020

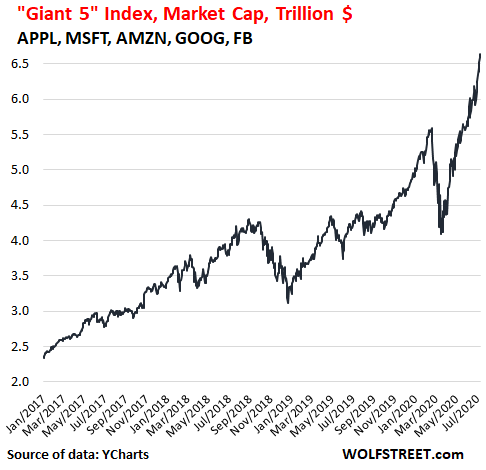

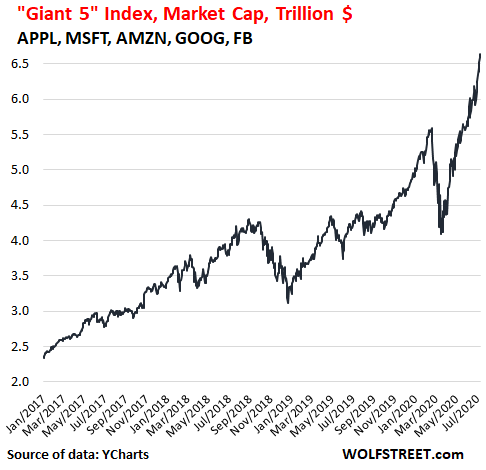

Wild Ride to Nowhere: The Giant 5

The “Giant 5” – Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, and Facebook – had another good day on Friday, with their combined market capitalization rising by 0.6% to another new high of $6.64 trillion, continuing a spike that started on March 16 and now measures 62.2%. In dollar terms, five stocks gained $2.54 trillion in less than four months.

Since January 1, 2017, my “Giant 5 Index” has soared by 184%, or by $4.3 trillion, with two sell-offs or crashes or whatever in between.

Even these days, when trillions fly by so fast that they’re hard to see, that’s still a huge increase in market value of just five companies in the span of three-and-a-half years (market cap data via YCharts):

The market capitalization – the number of shares outstanding times the current share price – of the Giant 5 has reached a breath-taking magnitude:

Apple [AAPL]: $1.66 trillion

Microsoft [MSFT]: $1.62 trillion

Amazon [AMZN]: $1.60 trillion

Alphabet [GOOG]: $1.05 trillion

Facebook [FB]: $699 billion.

How big are they compared to the entire stock market?

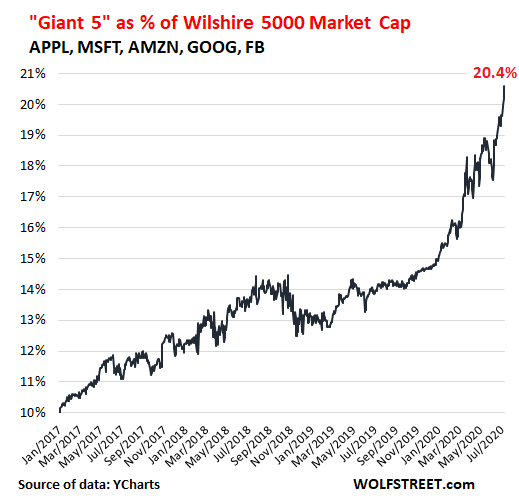

And I mean the entire US stock market, and not just the S&P 500. The Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index tracks all 3,415 or so US-listed companies. And the market cap of all those companies combined rose today to $32.47 trillion, up 44.4% from its crisis low on March 23.

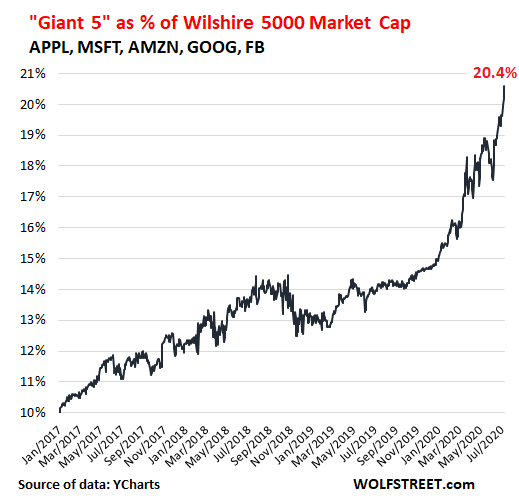

But as the shares of the Giant 5 have surged, the weight of the Giant 5 in the overall stock market has spiked from 17.5% on June 8 – that date will crop up again in a moment – to 20.4% today, and has more than doubled since January 2017, when the Giant 5 accounted for an already amazing 10% of the Wilshire 5000 (Wilshire 5000 data via YCharts):

On June 8 – here’s that date again – the stock market hit a Crisis high. The S&P 500 closed at 3,232, and the Wilshire 5000 at 32,936. As of Friday’s close, both the S&P 500 and the Wilshire 5000 remain below those June 8 levels.

But the Giant 5 Index, which was at $5.78 trillion on June 8, has since surged by 14%, to $6.6 trillion.

While the rest of the market has declined, the Giant 5 have surged. And, this surge in the Giant 5 obscured the decline in the rest of the market.

In other words, without the Giant 5, the rest of the market combined was a dud. And this is what has been happening for years!

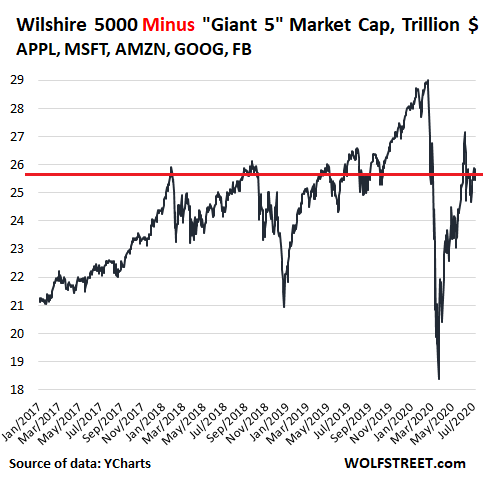

The Market Minus the Giant 5.

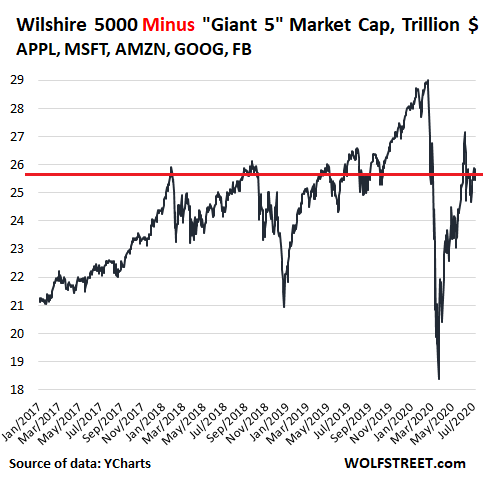

To see how the rest of the market is performing without these five stocks, I have created the “Wilshire 5000 minus the Giant 5 Index.” This shows what’s left of the entire stock market of 3,415 stocks, after removing these five giants.

The “Wilshire 5000 minus the Giant 5 Index” closed at $25,836 trillion today, still down 10.9% from the peak on February 19. Over the same period, the Giant 5 have soared 18.7%!

From the bottom in March, the “Wilshire 5000 minus the Giant 5” has surged 40.6%. The Giant 5 Index has skyrocketed 62.2%!

The “Wilshire 5000 minus the Giant 5 Index” is down 5.2% from June 8; down 10.9% from the high in February; down 1.2% from September 2018; and it’s just a tad below where it had been on January 26, 2018.

In other words, the rest of the stock market – all its winners and losers combined – without the Giant 5 and despite the horrendous volatility has gone nowhere since January 2018:

A miserable savings account would have outperformed the overall stock market without the Giant 5, and would have done so without all the horrendous volatility of the two sell-offs. Just five stocks whose market values have soared beyond imaginable magnitude pulled out the entire market.

And that’s a scary thought – that this entire market has become totally dependent on just five giant stocks with an immense concentration of power that have now come under regulatory security. And just as these stocks pulled up the entire market, they can pull down the entire market by their sheer weight.

Since January 1, 2017, my “Giant 5 Index” has soared by 184%, or by $4.3 trillion, with two sell-offs or crashes or whatever in between.

Even these days, when trillions fly by so fast that they’re hard to see, that’s still a huge increase in market value of just five companies in the span of three-and-a-half years (market cap data via YCharts):

The market capitalization – the number of shares outstanding times the current share price – of the Giant 5 has reached a breath-taking magnitude:

Apple [AAPL]: $1.66 trillion

Microsoft [MSFT]: $1.62 trillion

Amazon [AMZN]: $1.60 trillion

Alphabet [GOOG]: $1.05 trillion

Facebook [FB]: $699 billion.

How big are they compared to the entire stock market?

And I mean the entire US stock market, and not just the S&P 500. The Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index tracks all 3,415 or so US-listed companies. And the market cap of all those companies combined rose today to $32.47 trillion, up 44.4% from its crisis low on March 23.

But as the shares of the Giant 5 have surged, the weight of the Giant 5 in the overall stock market has spiked from 17.5% on June 8 – that date will crop up again in a moment – to 20.4% today, and has more than doubled since January 2017, when the Giant 5 accounted for an already amazing 10% of the Wilshire 5000 (Wilshire 5000 data via YCharts):

On June 8 – here’s that date again – the stock market hit a Crisis high. The S&P 500 closed at 3,232, and the Wilshire 5000 at 32,936. As of Friday’s close, both the S&P 500 and the Wilshire 5000 remain below those June 8 levels.

But the Giant 5 Index, which was at $5.78 trillion on June 8, has since surged by 14%, to $6.6 trillion.

While the rest of the market has declined, the Giant 5 have surged. And, this surge in the Giant 5 obscured the decline in the rest of the market.

In other words, without the Giant 5, the rest of the market combined was a dud. And this is what has been happening for years!

The Market Minus the Giant 5.

To see how the rest of the market is performing without these five stocks, I have created the “Wilshire 5000 minus the Giant 5 Index.” This shows what’s left of the entire stock market of 3,415 stocks, after removing these five giants.

The “Wilshire 5000 minus the Giant 5 Index” closed at $25,836 trillion today, still down 10.9% from the peak on February 19. Over the same period, the Giant 5 have soared 18.7%!

From the bottom in March, the “Wilshire 5000 minus the Giant 5” has surged 40.6%. The Giant 5 Index has skyrocketed 62.2%!

The “Wilshire 5000 minus the Giant 5 Index” is down 5.2% from June 8; down 10.9% from the high in February; down 1.2% from September 2018; and it’s just a tad below where it had been on January 26, 2018.

In other words, the rest of the stock market – all its winners and losers combined – without the Giant 5 and despite the horrendous volatility has gone nowhere since January 2018:

A miserable savings account would have outperformed the overall stock market without the Giant 5, and would have done so without all the horrendous volatility of the two sell-offs. Just five stocks whose market values have soared beyond imaginable magnitude pulled out the entire market.

And that’s a scary thought – that this entire market has become totally dependent on just five giant stocks with an immense concentration of power that have now come under regulatory security. And just as these stocks pulled up the entire market, they can pull down the entire market by their sheer weight.

by Wolf Richter, Wolf Street | Read more:

Images: Wolf Street

"Cancel Culture," Race and the Greed of the Billionaire Class

The elites will discuss race. They will not discuss class.

—Chris Hedges

But Hedges summarizes the situation so well, he’s well worth quoting: (...)

The cancel culture — the phenomenon of removing or canceling people, brands or shows from the public domain because of offensive statements or ideologies — is not a threat to the ruling class. Hundreds of corporations, nearly all in the hands of white executives and white board members, enthusiastically pumped out messages on social media condemning racism and demanding justice after George Floyd was choked to death by police in Minneapolis. Police, which along with the prison system are one of the primary instruments of social control over the poor, have taken the knee, along with Jamie Dimon, the chief executive of the serially criminal JPMorgan Chase, where only 4 percent of the top executives are Black. Jeff Bezos, the richest man in the world whose corporation, Amazon, paid no federal income taxes last year and who fires workers that attempt to unionize and tracks warehouse laborers as if they were prisoners, put a “Black Lives Matter” banner on Amazon’s home page.

The rush by the ruling elites to profess solidarity with the protestors and denounce racist rhetoric and racist symbols, supporting the toppling of Confederate statues and banning the Confederate flag, are symbolic assaults on white supremacy. Alone, these gestures will do nothing to reverse the institutional racism that is baked into the DNA of American society. The elites will discuss race. They will not discuss class.To repeat: Hundreds of corporations, nearly all in the hands of white executives and white board members, enthusiastically pumped out messages on social media condemning racism and demanding justice after George Floyd was choked to death by police in Minneapolis.

In addition, we’re drowning in corporate self-polishing-apple ads, like those from Nike and MacDonalds touting how much they care about the market that buys their products, even as they exploit that market for all they can get take it for.

Is it not more than obvious at this point, that corporate America and the purchased “free-market” liberals they keep in office are using this racially charged moment — a moment that should be racially charged — to distract from the other crisis facing America, the one where “minimum wage workers cannot afford rent in any U.S. state,” to cite just one of the hundred brutal tortures they inflict on us daily? (...)

As one wag put it, Jeff Bezos is having a very good crisis.

Companies large enough to survive this event are flush with cash and gobbling failed competitors hand over fist. It’s been rightly said that when Covid has done its work, we won’t recognize the country it left behind.

The “cancel culture” war is a distraction, important though it is we have that discussion. While we watch the knife fight in the corner, cheering one side or the other on, the main event, the torched and burning town we all inhabit, consumes itself behind us.

by Thomas Neuberger, (Down With Tyranny) via Naked Capitalism | Read more:

[ed. From the comments:]

Joe

July 17, 2020 at 4:28 am

This captures many of the thoughts I’ve been having for the past few weeks. I live in Houston, a city with the highest rate of uninsured people in the U.S., who are mostly black and brown. Our ICUs are overloaded with COVID patients, and our morgues are filling up rapidly. Across the country, millions of Americans are about to lose their unemployment insurance, get laid off, evicted, foreclosed on, or some combination thereof. Thanks to a bipartisan commitment to socialism for the rich only, the billionaire class is getting richer and consolidating even more wealth and power in their hands. But where is the left? Instead of either a coherent strategy to help the unemployed, the foreclosed, the evicted and the sick and dying, or to challenge the oligarchs and the politicians they control, I am stunned to see our largely university-based, middle class left relitigating the same debates about political correctness and identity politics they had thirty years ago (now rebranded as the “cancel culture”), almost oblivious to the economic suffering around them.... I am not even talking about folks toppling Confederate monuments, which I support. I am talking about all the bullshit chatter about “cancel culture” this and “woke” that from Jacobin DSAers to New Yorker liberals. The massive amount of energy expended on arguing over symbolism at a time like this just shows how out of touch the middle class left is with working people and their needs. It makes me sick.

Joe

July 17, 2020 at 4:28 am

This captures many of the thoughts I’ve been having for the past few weeks. I live in Houston, a city with the highest rate of uninsured people in the U.S., who are mostly black and brown. Our ICUs are overloaded with COVID patients, and our morgues are filling up rapidly. Across the country, millions of Americans are about to lose their unemployment insurance, get laid off, evicted, foreclosed on, or some combination thereof. Thanks to a bipartisan commitment to socialism for the rich only, the billionaire class is getting richer and consolidating even more wealth and power in their hands. But where is the left? Instead of either a coherent strategy to help the unemployed, the foreclosed, the evicted and the sick and dying, or to challenge the oligarchs and the politicians they control, I am stunned to see our largely university-based, middle class left relitigating the same debates about political correctness and identity politics they had thirty years ago (now rebranded as the “cancel culture”), almost oblivious to the economic suffering around them.... I am not even talking about folks toppling Confederate monuments, which I support. I am talking about all the bullshit chatter about “cancel culture” this and “woke” that from Jacobin DSAers to New Yorker liberals. The massive amount of energy expended on arguing over symbolism at a time like this just shows how out of touch the middle class left is with working people and their needs. It makes me sick.

The Next Disaster Is Just a Few Days Away

Millions of unemployed Americans face imminent catastrophe.

Some of us knew from the beginning that Donald Trump wasn’t up to the job of being president, that he wouldn’t be able to deal with a crisis that wasn’t of his own making. Still, the magnitude of America’s coronavirus failure has shocked even the cynics.

At this point Florida alone has an average daily death toll roughly equal to that of the whole European Union, which has 20 times its population.

How did this happen? One key element in our deadly debacle has been extreme shortsightedness: At every stage of the crisis Trump and his allies refused to acknowledge or get ahead of disasters everyone paying attention clearly saw coming.

Blithe denials that Covid-19 posed a threat gave way to blithe denials that rapid reopening would lead to a new surge in infections; now that the surge is upon us, Republican governors are responding sluggishly and grudgingly, while the White House is doing nothing at all.

Blithe denials that Covid-19 posed a threat gave way to blithe denials that rapid reopening would lead to a new surge in infections; now that the surge is upon us, Republican governors are responding sluggishly and grudgingly, while the White House is doing nothing at all.

And now another disaster — this time economic rather than epidemiological — is just days away.

To understand the cliff we’re about to plunge over, you need to know that while America’s overall handling of Covid-19 was catastrophically bad, one piece — the economic response — was actually better than many of us expected. The CARES Act, largely devised by Democrats but enacted by a bipartisan majority late in March, had flaws in both design and implementation, yet it did a lot both to alleviate hardship and to limit the economic fallout from the pandemic.

In particular, the act provided vastly increased aid to workers idled by lockdowns imposed to curb the spread of the coronavirus. U.S. unemployment insurance is normally a weak protection against adversity: Many workers aren’t covered, and even those who are usually receive only a small fraction of their previous wages. But the CARES Act both expanded coverage, for example to gig workers, and sharply increased benefits, adding $600 to every recipient’s weekly check.

These enhanced benefits did double duty. They meant that there was far less misery than one might otherwise have expected from a crisis that temporarily eliminated 22 million jobs; by some measures poverty actually declined.

They also helped sustain those parts of the economy that weren’t locked down. Without those emergency benefits, laid-off workers would have been forced to slash spending across the board. This would have generated a whole second round of job loss and economic contraction, as well as creating a huge wave of missed rental payments and evictions.

So enhanced unemployment benefits have been a crucial lifeline to tens of millions of Americans. Unfortunately, all of those beneficiaries are now just a few days from being thrown overboard.

For that $600 weekly supplement — which accounts for most of the expansion of benefits — applies only to benefit weeks that end “on or before July 31.” July 31 is a Friday. State unemployment benefit weeks typically end on Saturday or Sunday. So the supplement will end, in most places, on July 25 or 26, and millions of workers will see their incomes plunge 60 percent or more just a few days from now.