Tuesday, September 20, 2022

Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers

[ed. The climate change song.]

Unpredictable Reward, Predictable Happiness

[Epistemic status: very conjectural. I am not a neuroscientist and they should feel free to tell me if any of this is totally wrong.]

I.

Seen on the subreddit: You Seek Serotonin, But Dopamine Can’t Deliver. Commenters correctly ripped apart its neuroscience; for one thing, there’s no evidence people actually “seek serotonin”, or that serotonin is involved in good mood at all. Sure, it seems to have some antidepressant effects, but these are weak and probably far downstream; even though SSRIs increase serotonin within hours, they take weeks to improve mood. Maxing out serotonin levels mostly seems to cause a blunted state where patients can’t feel anything at all.

In contrast, the popular conception of dopamine isn’t that far off. It does seem to play some kind of role in drive/reinforcement/craving, although it also does many, many other things. And something like the article’s point - going after dopamine is easy but ultimately unsatisfying - is something I’ve been thinking about a lot.

Any neuroscience article will tell you that the “reward center” of the brain - the nucleus accumbens - monitors actual reward minus predicted reward. Or to be even more finicky, currently predicted reward minus previously predicted reward. Imagine that on January 1, you hear that you won $1 billion in the lottery. It’s a reputable lottery, they’re definitely not joking, and they always pay up. They tell you that it’ll take a month for them to get the money in your account, and you should expect it February 1. You’re going to be really busy the whole month of February, so you decide not to start spending until March 1. What happens?

My guess is: January 1, when you first hear you won, is the best day of your life. February 1, when the money arrives in your account, is nice but not anywhere near as good. March 1, when you start spending the money, is pretty great because you go do lots of fun things.

However good you predicted your life would be last year, you make a big update January 1 when you hear you won the lottery. Nothing good has happened yet: you don’t have money and you’re not buying fancy things. But your predictions about your future levels of those things shoot way up, which corresponds to happiness and excitement. In contrast, on February 1 you have $1 billion more than on January 31, but because you predicted it would happen, it’s not that big a mood boost.

What about March 1? Suppose you do a few specific things - you buy a Ferrari, drive it around, and eat dinner in the fanciest restaurant in town. Do you enjoy these things? Presumably yes. Why? You knew all throughout February that you were planning to get a Ferrari and a fancy dinner today. And you knew that Ferraris and fancy dinners were pleasant; otherwise you wouldn’t have gotten them. So how come predicting you would get the money mostly cancels out the goodness of getting the money, but predicting you would get the Ferrari/dinner doesn’t cancel out the goodness of the Ferrari/dinner?

Or: suppose that every year I ate cake on my birthday. This is very predictable. But I would expect to still enjoy the cake. Why?

It seems like maybe there are two types of happiness: happiness that is cancelled out by predictability, and happiness that isn’t.

I.

Seen on the subreddit: You Seek Serotonin, But Dopamine Can’t Deliver. Commenters correctly ripped apart its neuroscience; for one thing, there’s no evidence people actually “seek serotonin”, or that serotonin is involved in good mood at all. Sure, it seems to have some antidepressant effects, but these are weak and probably far downstream; even though SSRIs increase serotonin within hours, they take weeks to improve mood. Maxing out serotonin levels mostly seems to cause a blunted state where patients can’t feel anything at all.

In contrast, the popular conception of dopamine isn’t that far off. It does seem to play some kind of role in drive/reinforcement/craving, although it also does many, many other things. And something like the article’s point - going after dopamine is easy but ultimately unsatisfying - is something I’ve been thinking about a lot.

Any neuroscience article will tell you that the “reward center” of the brain - the nucleus accumbens - monitors actual reward minus predicted reward. Or to be even more finicky, currently predicted reward minus previously predicted reward. Imagine that on January 1, you hear that you won $1 billion in the lottery. It’s a reputable lottery, they’re definitely not joking, and they always pay up. They tell you that it’ll take a month for them to get the money in your account, and you should expect it February 1. You’re going to be really busy the whole month of February, so you decide not to start spending until March 1. What happens?

My guess is: January 1, when you first hear you won, is the best day of your life. February 1, when the money arrives in your account, is nice but not anywhere near as good. March 1, when you start spending the money, is pretty great because you go do lots of fun things.

However good you predicted your life would be last year, you make a big update January 1 when you hear you won the lottery. Nothing good has happened yet: you don’t have money and you’re not buying fancy things. But your predictions about your future levels of those things shoot way up, which corresponds to happiness and excitement. In contrast, on February 1 you have $1 billion more than on January 31, but because you predicted it would happen, it’s not that big a mood boost.

What about March 1? Suppose you do a few specific things - you buy a Ferrari, drive it around, and eat dinner in the fanciest restaurant in town. Do you enjoy these things? Presumably yes. Why? You knew all throughout February that you were planning to get a Ferrari and a fancy dinner today. And you knew that Ferraris and fancy dinners were pleasant; otherwise you wouldn’t have gotten them. So how come predicting you would get the money mostly cancels out the goodness of getting the money, but predicting you would get the Ferrari/dinner doesn’t cancel out the goodness of the Ferrari/dinner?

Or: suppose that every year I ate cake on my birthday. This is very predictable. But I would expect to still enjoy the cake. Why?

It seems like maybe there are two types of happiness: happiness that is cancelled out by predictability, and happiness that isn’t.

by Scott Alexander, Astral Codex Ten | Read more:

[ed. Further:

"Here’s some advice for aspiring psychiatrists: never tell your patient “yeah, seems like you’re cursed to be perpetually unhappy”.

The closest I’ve ever come to violating that advice was with a patient who came in for trouble with (I’m randomizing their gender; it landed on male) his girlfriend.

He described his girlfriend in a way that made it clear she was abusive, emotionally manipulative, and had a bunch of completely-untreated psychiatric issues. He was well aware of all of this. He had tried breaking up with her a few times. Each time, all of his own issues went away, and his life was great. Then, each time, he got back together with her. So we did some therapy together for a while, tried to figure out why, and all I could ever get out of him was that she was more “exciting”. It was something about knowing that on any given day, she might either adore him or try to kill him. With every other partner he’d tried, it was either one or the other. With her it was some kind of perverse exactly-50-50 probability, and he was addicted to it."

The closest I’ve ever come to violating that advice was with a patient who came in for trouble with (I’m randomizing their gender; it landed on male) his girlfriend.

He described his girlfriend in a way that made it clear she was abusive, emotionally manipulative, and had a bunch of completely-untreated psychiatric issues. He was well aware of all of this. He had tried breaking up with her a few times. Each time, all of his own issues went away, and his life was great. Then, each time, he got back together with her. So we did some therapy together for a while, tried to figure out why, and all I could ever get out of him was that she was more “exciting”. It was something about knowing that on any given day, she might either adore him or try to kill him. With every other partner he’d tried, it was either one or the other. With her it was some kind of perverse exactly-50-50 probability, and he was addicted to it."

[ed. Damn... I can relate to that].

Bill Kirchen

[ed. Telecaster Master. All the styles and hits, starting at 2:30.]

Monday, September 19, 2022

These High School ‘Classics’ Have Been Taught For Generations

If you went to high school in the United States anytime since the 1960s, you were likely assigned some of the following books: Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet,” “Julius Caesar” and “Macbeth”; John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men”; F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby”; Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird”; and William Golding’s “The Lord of the Flies.”

For many former students, these books and other so-called “classics” represent high school English. But despite the efforts of reformers, both past and present, the most frequently assigned titles have never represented America’s diverse student body.

Why did these books become classics in the U.S.? How have they withstood challenges to their status? And will they continue to dominate high school reading lists? Or will they be replaced by a different set of books that will become classics for students in the 21st century? (...)

English education professor Arthur Applebee observed in 1989 that, since the 1960s, “leaders in the profession of English teaching have tried to broaden the curriculum to include more selections by women and minority authors.” But in the late 1980s, according to his findings, the high school “top ten” still included only one book by a woman – Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” – and none by minority authors.

At that time, a raging debate was underway about whether America was a “melting pot” in which many cultures became one, or a colorful “mosaic” in which many cultures coexisted. Proponents of the latter view argued for a multicultural canon, but they were ultimately unable to establish one. A 2011 survey of Southern schools by Joyce Stallworth and Louel C. Gibbons, published in “English Leadership Quarterly,” found that the five most frequently taught books were all traditional selections: “The Great Gatsby,” “Romeo and Juliet,” Homer’s “The Odyssey,” Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible” and “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

One explanation for this persistence is that the canon is not simply a list: It takes form as stacks of copies on shelves in the storage area known as the “book room.” Changes to the inventory require time, money and effort. Depending on the district, replacing a classic might require approval by the school board. And it would create more work for teachers who are already maxed out. (...)

[ed. I have a friend who teaches social studies (mainly so he can coach) and it sounds like the same basic curriculum I had in high school. We're boring generations of kids to death with literature that's boring even to me, and memorizing mind-numbing facts (Mesopotamia, anyone? The Renaissance? Every war since the beginning of time?). Why not instead teach critical thinking and research skills and let them find their own levels of interest? Oh, and civics. Please don't short shrift civics.]

For many former students, these books and other so-called “classics” represent high school English. But despite the efforts of reformers, both past and present, the most frequently assigned titles have never represented America’s diverse student body.

Why did these books become classics in the U.S.? How have they withstood challenges to their status? And will they continue to dominate high school reading lists? Or will they be replaced by a different set of books that will become classics for students in the 21st century? (...)

English education professor Arthur Applebee observed in 1989 that, since the 1960s, “leaders in the profession of English teaching have tried to broaden the curriculum to include more selections by women and minority authors.” But in the late 1980s, according to his findings, the high school “top ten” still included only one book by a woman – Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” – and none by minority authors.

At that time, a raging debate was underway about whether America was a “melting pot” in which many cultures became one, or a colorful “mosaic” in which many cultures coexisted. Proponents of the latter view argued for a multicultural canon, but they were ultimately unable to establish one. A 2011 survey of Southern schools by Joyce Stallworth and Louel C. Gibbons, published in “English Leadership Quarterly,” found that the five most frequently taught books were all traditional selections: “The Great Gatsby,” “Romeo and Juliet,” Homer’s “The Odyssey,” Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible” and “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

One explanation for this persistence is that the canon is not simply a list: It takes form as stacks of copies on shelves in the storage area known as the “book room.” Changes to the inventory require time, money and effort. Depending on the district, replacing a classic might require approval by the school board. And it would create more work for teachers who are already maxed out. (...)

Esau McCauley, the author of “Reading While Black,” describes the list of classics by white authors as the “pre-integration canon.” At least two factors suggest that its dominance over the curriculum is coming to an end.

First, the battles over which books should be taught have become more intense than ever. On the one hand, progressives like the teachers of the growing #DisruptTexts movement call for the inclusion of books by Black, Native American and other authors of color - and they question the status of the classics. On the other hand, conservatives have challenged or successfully banned the teaching of many new books that deal with gender and sexuality or race.

PEN America, a nonprofit organization that fights for free expression for writers, reports “a profound increase” in book bans. The outcome might be a literature curriculum that more resembles the political divisions in this country. Much more than in the past, students in conservative and progressive districts might read very different books.

First, the battles over which books should be taught have become more intense than ever. On the one hand, progressives like the teachers of the growing #DisruptTexts movement call for the inclusion of books by Black, Native American and other authors of color - and they question the status of the classics. On the other hand, conservatives have challenged or successfully banned the teaching of many new books that deal with gender and sexuality or race.

PEN America, a nonprofit organization that fights for free expression for writers, reports “a profound increase” in book bans. The outcome might be a literature curriculum that more resembles the political divisions in this country. Much more than in the past, students in conservative and progressive districts might read very different books.

by Andrew Newman, The Conversation | Read more:

Image: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND Source: 1963: Scarvia Anderson; 1988: Arthur Applebee[ed. I have a friend who teaches social studies (mainly so he can coach) and it sounds like the same basic curriculum I had in high school. We're boring generations of kids to death with literature that's boring even to me, and memorizing mind-numbing facts (Mesopotamia, anyone? The Renaissance? Every war since the beginning of time?). Why not instead teach critical thinking and research skills and let them find their own levels of interest? Oh, and civics. Please don't short shrift civics.]

Labels:

Critical Thought,

Education,

Fiction,

Literature

Managing Alaska's Game Populations

For certain game populations, a quicker response is needed.

There are many factors involved in managing game populations. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game is saddled with that task. In discussing the subject with a biologist, numbers and studies will rule the conversation. Are numbers really the crux of management? (...)

Take a look at Nelchina caribou management. The goal is 35,000 critters, give or take. Harvest 5,000 caribou, replace the 5,000. That sounds easy.

However, to replace the desired animals we need to determine a few variables. What is our optimum bull/cow ratio? How many bulls will the hunters get? How many will the wolves get? What will the winter kill be? These factors cause things to get a little dicey.

Let’s complicate management a bit more. How much snow will we get this winter? Will it melt early enough for the cows to reach the calving grounds? High rivers or a rainy summer might cause excessive mortality on young caribou, thus affecting projected recruitment.

Biologists must also factor in how many Nelchina caribou join the 40-Mile caribou herd. The two herds have wintering grounds in common. Nelchina caribou wintered from Mount Sanford all of the way to Dawson last season. Did some join the Porcupine herd? Fish and Game says it doesn’t think so.

How many caribou taken in the 40-Mile hunt might have been Nelchina animals? The 40-Mile seasons have been quite liberal the past few years. We do know that the 2022 Nelchina population estimate is now on the low side of 21,000 animals. This is down from the estimate of 35,000-40,000 animals a year ago. That’s around 15,000 missing animals.

There is an estimate of a 10% loss of Nelchina caribou into the 40-Mile herd. This is based on two out of 20 collared cows. Small sample. The winter kill estimate that 30% of the cows did not survive is based on the same sample.

However, the population of the 40-Mile herd is also down. The 40,000 population estimate is down considerably from the estimate of several years ago. In addition to interacting with the Nelchina herd, the 40-Mile animals also may cross paths with the Porcupine herd, though that is an unknown at this time.

The population estimate on the Porcupine Herd is very rough at this time. That herd ranges well into Canada. The winter range certainly intersects both that of the 40-Mile and Nelchina herds, at least last winter.

Browse availability must also be considered. Caribou feed primarily on wheat grass and lichens during the winter months. Summer feed is similar with the addition of some seasonal plants such as fireweed, dwarf birch and willow. What does the status of available browse need to be to have a happy, returning caribou herd? Nobody knows that. There may be some older reindeer herders who have an anecdotal handle on that, but who talks to them?

As you can see, very few of the factors affecting proliferation of caribou are predictable or controllable.

The only guarantees are politics and regulation. There are many special interest groups who wish to shoot at a caribou. Some want them for food. For others the priority is the hunt itself. There are five separate permit hunts for Nelchina caribou. There is also a community hunt and a federal subsistence hunt. The details of these hunts are not important. What is important is the various groups that have lobbied and harassed successfully for these hunts. This is politics — not biology.

Take a look at Nelchina caribou management. The goal is 35,000 critters, give or take. Harvest 5,000 caribou, replace the 5,000. That sounds easy.

However, to replace the desired animals we need to determine a few variables. What is our optimum bull/cow ratio? How many bulls will the hunters get? How many will the wolves get? What will the winter kill be? These factors cause things to get a little dicey.

Let’s complicate management a bit more. How much snow will we get this winter? Will it melt early enough for the cows to reach the calving grounds? High rivers or a rainy summer might cause excessive mortality on young caribou, thus affecting projected recruitment.

Biologists must also factor in how many Nelchina caribou join the 40-Mile caribou herd. The two herds have wintering grounds in common. Nelchina caribou wintered from Mount Sanford all of the way to Dawson last season. Did some join the Porcupine herd? Fish and Game says it doesn’t think so.

How many caribou taken in the 40-Mile hunt might have been Nelchina animals? The 40-Mile seasons have been quite liberal the past few years. We do know that the 2022 Nelchina population estimate is now on the low side of 21,000 animals. This is down from the estimate of 35,000-40,000 animals a year ago. That’s around 15,000 missing animals.

There is an estimate of a 10% loss of Nelchina caribou into the 40-Mile herd. This is based on two out of 20 collared cows. Small sample. The winter kill estimate that 30% of the cows did not survive is based on the same sample.

However, the population of the 40-Mile herd is also down. The 40,000 population estimate is down considerably from the estimate of several years ago. In addition to interacting with the Nelchina herd, the 40-Mile animals also may cross paths with the Porcupine herd, though that is an unknown at this time.

The population estimate on the Porcupine Herd is very rough at this time. That herd ranges well into Canada. The winter range certainly intersects both that of the 40-Mile and Nelchina herds, at least last winter.

Browse availability must also be considered. Caribou feed primarily on wheat grass and lichens during the winter months. Summer feed is similar with the addition of some seasonal plants such as fireweed, dwarf birch and willow. What does the status of available browse need to be to have a happy, returning caribou herd? Nobody knows that. There may be some older reindeer herders who have an anecdotal handle on that, but who talks to them?

As you can see, very few of the factors affecting proliferation of caribou are predictable or controllable.

The only guarantees are politics and regulation. There are many special interest groups who wish to shoot at a caribou. Some want them for food. For others the priority is the hunt itself. There are five separate permit hunts for Nelchina caribou. There is also a community hunt and a federal subsistence hunt. The details of these hunts are not important. What is important is the various groups that have lobbied and harassed successfully for these hunts. This is politics — not biology.

by John Schandelmeier, Anchorage Daily News | Read more:

Image: Dean Biggins, USFWS, Creative Commons

[ed. See also: Nelchina Caribou News (pdf) - Alaska Dept. Fish and Game.]

[ed. See also: Nelchina Caribou News (pdf) - Alaska Dept. Fish and Game.]

Labels:

Animals,

Biology,

Environment,

Government,

Science

Sunday, September 18, 2022

Aaron Marcus, from Symbolic Constructions series, 1971-1972, in TM Typographische Monatsblätter, Issue 10, 1973, TM Research Archive

via:

via:

Your Local Self-Inflicted Housing Crisis Ouroboros

Imagine you’re a master carpenter. You’ve been building furniture and casework for many years. You have a style that you’ve developed, and a loyal customer base that loves your products…

When building for commercial applications, there are code requirements around fire safety, VOCs, and other health/safety issues.

When building for commercial applications, there are code requirements around fire safety, VOCs, and other health/safety issues.

These are clearly written and you’ve always been able to document and adhere to them on your own without much trouble.

One day it’s announced that the government has a new process for ensuring the quality and safety of your work. From now on, a panel representing several city departments will review your designs before they can be sold. Sounds reasonable, right?

You attend your first review meeting.

One day it’s announced that the government has a new process for ensuring the quality and safety of your work. From now on, a panel representing several city departments will review your designs before they can be sold. Sounds reasonable, right?

You attend your first review meeting.

None of the reviewers have ever worked in carpentry, or any related field. A couple have taken one or two woodworking classes in school or university.

They range between 25-35 years old, but most are in their 20’s.

The first hour is spent asking you how you plan to meet the safety regulations that you’ve already been meeting for many years.

The first hour is spent asking you how you plan to meet the safety regulations that you’ve already been meeting for many years.

They ask you to submit documentation formally for further review. They will circulate your docs for comment by each dept and ask for revisions.

The panel makes it clear that your actual work methods and products won’t need to change at all.

The panel makes it clear that your actual work methods and products won’t need to change at all.

But you should expect a few rounds of comments to properly document these safety measures, and this process will take several months prior to final approval.

Next up, design review.

Next up, design review.

A 26 year old with an industrial design degree, but no experience in manufacturing, kicks things off.

He congratulates you on your very nice work, but then says that he has some concerns that he’d like you to consider.

First off, some of your materials are sourced from British Columbia, and he would really like to see more local materials used. He recognizes that this might increase costs. But please consider local materials.

First off, some of your materials are sourced from British Columbia, and he would really like to see more local materials used. He recognizes that this might increase costs. But please consider local materials.

You are confused, and ask if this is a requirement or a suggestion.

He says it’s not a requirement, but strongly encouraged. He will review your formal response, and will provide further guidance at that time. You have no idea whether this is something you actually need to do.

He says it’s not a requirement, but strongly encouraged. He will review your formal response, and will provide further guidance at that time. You have no idea whether this is something you actually need to do.

This will become a common theme for the meeting.

Next, he is concerned about climate change and thinks that you should consider using more sustainable wood, perhaps bamboo.

Next, he is concerned about climate change and thinks that you should consider using more sustainable wood, perhaps bamboo.

You explain that bamboo isn’t appropriate for all projects, but you’re happy to use it when it makes sense.

The reviewer seems annoyed…

“Climate change is the greatest challenge of our time and I think you should take it seriously.”

“Climate change is the greatest challenge of our time and I think you should take it seriously.”

You don’t know what to say to this, so you say nothing.

Next up, he notices that all of your designs for chairs have four legs. He asks why.

Next up, he notices that all of your designs for chairs have four legs. He asks why.

Image: uncredited

Microneedle Tattoo Technique: Painless and Fast

Painless, bloodless tattoos have been created by scientists, who say the technique could have medical and cosmetic applications.

The technique, which can be self-administered, uses microneedles to imprint a design into the skin without causing pain or bleeding. Initial applications are likely to be medical – but the team behind the innovation hope that it could also be used in tattoo parlours to provide a more comfortable option.

“This could be a way not only to make medical tattoos more accessible, but also to create new opportunities for cosmetic tattoos because of the ease of administration,” said Prof Mark Prausnitz, who led the work at Georgia Institute of Technology. “While some people are willing to accept the pain and time required for a tattoo, we thought others might prefer a tattoo that is simply pressed on to the skin and does not hurt.” (...)

Tattoos typically use large needles to puncture the skin between 50 and 3,000 times a minute to deposit ink below the surface, a time-consuming and painful process. The Georgia Tech team has developed microneedles made of tattoo ink encased in a dissolvable matrix. By arranging the microneedles in a specific pattern, each one acts like a pixel to create a tattoo image in any shape or pattern, and a variety of colours can be used.

The technique, which can be self-administered, uses microneedles to imprint a design into the skin without causing pain or bleeding. Initial applications are likely to be medical – but the team behind the innovation hope that it could also be used in tattoo parlours to provide a more comfortable option.

“This could be a way not only to make medical tattoos more accessible, but also to create new opportunities for cosmetic tattoos because of the ease of administration,” said Prof Mark Prausnitz, who led the work at Georgia Institute of Technology. “While some people are willing to accept the pain and time required for a tattoo, we thought others might prefer a tattoo that is simply pressed on to the skin and does not hurt.” (...)

Tattoos typically use large needles to puncture the skin between 50 and 3,000 times a minute to deposit ink below the surface, a time-consuming and painful process. The Georgia Tech team has developed microneedles made of tattoo ink encased in a dissolvable matrix. By arranging the microneedles in a specific pattern, each one acts like a pixel to create a tattoo image in any shape or pattern, and a variety of colours can be used.

ContraPoints: The Hunger

[ed. Natalie Wynn is a gem and sharp as a tack. See also: ‘The internet is about jealousy’: YouTube muse ContraPoints on cancel culture and compassion (The Guardian). Sample from the video: "Is this a joke to you? Do you find this humorous? Yeah. I don't because I have glimpsed the gates of Hell, where unrepentant souls endure the horrors of sin. Away from God, shut out from grace, tormented by unyielding guilt and shame. Yes, we've all been to Cincinnati." Haha..]

Labels:

Critical Thought,

Culture,

Humor,

Politics,

Religion

A Sunday Waltz

How my music got featured in 'Better Call Saul'

A lot of surprising things have happened to me lately, but getting on the hottest show in TV wasn’t on my bingo card. Yet, against all odds, a composition I recorded back in 1986 got showcased on Better Call Saul this week.

People are asking me how I pulled this off. But I didn’t do anything. For the most part it happened without me even aware of what was going on...

People are asking me how I pulled this off. But I didn’t do anything. For the most part it happened without me even aware of what was going on...

The story begins back in the mid-1980s, when I was preparing to record my first album, The End of the Open Road. I composed a waltz, languid and bittersweet—but I didn’t know what to do with it.

This was a frequent problem back then. I was a jazz musician preparing to record a jazz album, but the compositions I wrote often didn’t sound very jazzy. The music came to me in moments of inspiration, and it felt right, but it was free-floating and impressionistic, maybe even cinematic—and certainly not something you would play at a jazz club.

I soon had several of these compositions in my repertoire (such as this piece and this other piece)—and I never performed them on the gig. They just weren’t right for a jazz band. But I did play them for my own enjoyment when I was alone at the piano.

And then there was this pastoral composition in 3/4—I called it “A Sunday Waltz.” This is the piece that got featured in Better Call Saul. It was another of my private musical reveries, played solely for myself in secluded moments at the keyboard. (...)

So when I finally made my record at the Music Annex in Menlo Park, I still had a little bit of studio time left after the rest of the band went home. I decided that I might as well record some of these solo piano vignettes—what’s the downside?

by Ted Gioia, The Honest Broker | Read more:

Image: YouTube

Why is the Oldest Book in Europe a Work of Music Criticism? (Part 1 of 2)

[ed. Part 2 here.]

They didn’t know it at the time, but they had discovered a burial ground near the ancient city of Lete. Judging by the weapons, armor, and precious items, it had served as a gravesite for affluent families with soldiering backgrounds.

Here among the remnants of a funeral pyre on top of a slab covering one of the graves, they found a carbonized papyrus. Experts later determined that this manuscript was, in the words of classicist Richard Janko, “the oldest surviving European book.”

The discovery of any ancient papyrus in Greece would be a matter for celebration. Due to the hot, humid weather, these documents have not survived into modern times. In this case, a mere accident led to the preservation of the Derveni papyrus—the intention must have been to destroy it in the funeral pyre. The papyrus had probably been placed in the hands of the deceased before cremation, but instead of burning, much of it had been preserved by the resulting carbonization.

Mere happenstance, it seems, allowed the survival of a document literally consigned to the flames. And what was in this astonishing work, a text so important that its owner wanted to carry it with him to the afterlife?

Strange to say, it was a book of music criticism. (...)

But if this is an amazing kind of musicology, it’s also an embarrassment. Maybe that’s why I’ve never heard a single musicologist mention the Derveni papyrus—although it is arguably the original source in the Western world of their own academic specialty. Things aren't much better in the various academic disciplines of ancient studies, built largely on celebrating the rational and literary achievements of the distant past. For classicists, the claims presented in this papyrus are awkward from almost every angle.

The Derveni author was clearly smart and educated, a seer among the ranks of magi, but hardly operating from the same playbook as Plato and Aristotle—those paragons of logic and clear thinking. At first glance, this sage seems more like those roadside psychics working out of low-rent strip malls, who tell your future and bill twenty-five dollars to your credit card.

But this magical mumbo-jumbo was just a start of the many controversies surrounding the Derveni papyrus. As subsequent events proved, almost every aspect of this ancient text would be scrutinized, disputed, and—most of all—cleansed in an attempt to make it seem less like wizardry, and more like the scripture of an organized religion, perhaps similar to the teachings of a sober Protestant sect, or the tenets of a formal philosophy, similar to those taught in respectable universities.

We will need to sort out a few of these troubling issues, which have considerable bearings on our understanding of the origins of music, and even its potential uses in our own times. But before proceeding, I must point out a disturbing pattern I’ve noticed over the course of decades studying the sources of musical innovation: namely, that many of the most important surviving documents were preserved only by chance, and frequently were intended for destruction—and, when they have survived, they have frequently been subjected to purifying distortions of the same kind involved here.

In fact, it’s surprising how often musical innovators are completely obliterated from the historical record. And if you pay attention you notice something eerie and unsettling: the more powerful the music, the more the innovators risk erasure. We are told that Buddy Bolden was the originator of jazz—but not a single recording survives (or perhaps was ever made). W.C. Handy is lauded as the “Father of the Blues,” but by his own admission he didn’t invent the music, but learned it from a mysterious African-American guitarist who performed at the train station in Tutwiler, Mississippi. In that instance, not only did no recordings survive, but we don’t even know the Tutwiler guitarist’s name.

Even the venerated genres of Western classical music originate from these same shadowy places. Only a few musical fragments survive from the score of the first opera, Jacopo Peri’s Dafne; and Angelo Poliziano’s Orfeo, an earlier work that laid the groundwork for the art form, is even more enigmatic. Not only has none of its music survived, but we aren’t entirely sure of the year it was staged, the makeup of the orchestra, or the names of the musicians who might have assisted Poliziano in the creation of the work. Yet such mysteries are hardly exceptions but rather the norm in the long history of musical innovation, so murky and imprecise and resisting the neat timelines we find in other fields of human endeavor.

Inventors and innovators in math, science, and technology are remembered by posterity, but for some reason the opposite is true in music. If you are a great visionary in music, your life is actually at danger (as we shall see below). But, at a minimum, your achievement is removed from the history books. If you think I’m exaggerating, convene a group of music historians and ask them to name the inventor of the fugue, the sonata, the symphony, or any other towering achievement of musical culture, and note the looks of consternation that ensue, even before the arguments begin. (...)

We can trace this story of musical destruction all the way to the present day, and share accounts of parents and other authority figures literally burning recordings of rock, blues, hip-hop, metal, and other styles of disruptive music—songs possessing an alluring power over hearers almost identical to what Plato warned against back in ancient Greece. In 1979 the demolition of a box of disco records with explosives—as part of a publicity stunt to get fans to attend a Chicago White Sox baseball double-header—turned into a full-fledged riot, with 39 people arrested. Some people will tell you that the age of disco music ended because of that incident. But the destruction didn’t stop there. Just a few years ago, a minor league baseball team attracted a crowd by blowing up Justin Bieber and Miley Cyrus’s music and merchandise in a giant (and aptly-named) boombox. In fact, you could write a whole book about people burning and blowing up music.

But why do we destroy music? In the pages ahead, I will suggest that songs have always played a special role in defining the counterculture and serving as a pathway to experiences outside accepted norms. They are not mere entertainment, as many will have you believe, but exist as an entry point to an alternative universe immune to conventional views and acceptable notions. As such, songs still possess magical power as a gateway on a life-changing quest. And though we may have stopped burning witches at the stake, we still fear their sorcery, and consign to the flames those devilish songs that contain it.

by Ted Gioia, The Honest Broker | Read more:

Images: Wikimedia Commons; Buddy Bolden/uncredited

[ed. After a disastrous week in which a good chunk of posts on this blog were lost, I'd like to return with Ted Gioia and the first installment from his new book Music to Raise the Dead (The Secret Origins of Musicology). The plan is to release one chapter a month on his website The Honest Broker. Part 2 is here. Ted is a treasure (as a music critic, historian, and all-around interesting and knowledgeable guy), and if you're not familiar with him, or only vaguely so, I urge you to check out all his posts (including this one about effective public speaking). He also has a number of YouTube videos on various music subjects as well (for example, here, here and here).]

Labels:

Critical Thought,

history,

Literature,

Music,

Philosophy

Saturday, September 17, 2022

Technical Difficulties

Greetings Duck Soup readers. I'm currently working through some technical difficulties and hope to resume normal operations shortly. Please be patient. Unfortunately posts from the last year or so have been lost and it looks like they can't be retrieved.

markk

Tuesday, August 31, 2021

Dialogues Between Neuroscience and Society: Music and the Brain With Pat Metheny

Tuesday, August 24, 2021

Tony Joe White

[ed. Been learning a few TJW songs lately. Including this one.]

How Should an Influencer Sound?

For 10 straight years, the most popular way to introduce oneself on YouTube has been a single phrase: “Hey guys!” That’s pretty obvious to anyone who’s ever watched a YouTube video about, well, anything, but the company still put in the energy to actually track the data over the past decade. “What’s up” and “good morning” come in at second and third, but “hey guys” has consistently remained in the top spot. (Here is a fun supercut of a bunch of YouTubers saying it until the phrase ceases to mean anything at all.)

This is not where the sonic similarities of YouTubers, regardless of their content, end. For nearly as long as YouTube has existed, people have been lamenting the phenomenon of “YouTube voice,” or the slightly exaggerated, over-pronounced manner of speaking beloved by video essayists, drama commentators, and DIY experts on the platform. The ur-example cited is usually Hank Green, who’s been making videos on everything from the American health care system to the “Top 10 Freaking Amazing Explosions” since literally 2007.

Actual scholars have attempted to describe what YouTube voice sounds like. Speech pathologist and PhD candidate Erin Hall told Vice that there are two things happening here: “One is the actual segments they’re using — the vowels and consonants. They’re over-enunciating compared to casual speech, which is something newscasters or radio personalities do.” Second: “They’re trying to keep it more casual, even if what they’re saying is standard, adding a different kind of intonation makes it more engaging to listen to.”

In an investigation into YouTube voice, the Atlantic drew from several linguists to determine what specific qualities this manner of speaking shares. Essentially, it’s all about pronunciation and pacing. On camera, it takes more effort to keep someone interested (see also: exaggerated hand and facial motions). “Changing of pacing — that gets your attention,” said linguistics professor Naomi Baron. Baron noted that YouTubers tended to overstress both vowels and consonants, such as someone saying “exactly” like “eh-ckzACKTly.” She guesses that the style stems in part from informal news broadcast programs or “infotainment” like The Daily Show. Another, Mark Liberman of the University of Pennsylvania, put it bluntly: It’s “intellectual used-car-salesman voice,” he wrote. He also compared it to a carnival barker. (...)

Last week a TikTok came on my For You page that explored digital accents. TikToker @Averybrynn was referringspecifically to what she called the “beauty YouTuber dialect,” which she described as “like they weirdly pronounce everything just a little bit too much in these small little snippets?” What makes it distinct from regular YouTube voice is that each word tends to be longer than it should, while also being bookended by a staccato pause. There’s also a common inclination to turn short vowels into long vowels, like saying “thee” instead of “the.” Others in the comments pointed out the repeated use of the first person plural when referring to themselves (“and now we’re gonna go in with a swipe of mascara”), while one linguistics major noted that this was in fact a “sociolect,” not a dialect, because it refers to a social group.

It’s the sort of speech typically associated with female influencers who, by virtue of the job, we assume are there to endear themselves to the audience or present a trustworthy sales pitch. But what’s most interesting to watch about YouTube voice and the influencer accent is how normal people have adapted to it in their own, regular-person TikTok videos and Instagram stories. If you listen closely to enough people’s front-facing camera videos, you’ll hear a voice that sounds somewhere between a TED Talk and sponsored content, perhaps even within your own social circles. Is this a sign that as influencer culture bleeds into our everyday lives, many of the quirks that professionals use will become normal for us too? Maybe! Is it a sign that social platforms are turning us all into salespeople? Also maybe!

But here’s the question I haven’t heard anyone ask yet: If everyone finds these ways of speaking annoying to some degree, then how should people actually talk into the camera?

by Rebecca Jennings, Vox | Read more:

Image: YouTube/Anyone Can Play Guitar

[ed. Got the link for this article from one of my top three favorite online guitar instructors: Adrian Woodward, who normally sounds like a cross between Alfred Hitchcock and the Geico gecko. Here he tries a YouTube voice for fun. If you're a guitar player, do check out his instruction videos on YouTube at Anyone Can Play Guitar. High quality, and great dry personality.]

This is not where the sonic similarities of YouTubers, regardless of their content, end. For nearly as long as YouTube has existed, people have been lamenting the phenomenon of “YouTube voice,” or the slightly exaggerated, over-pronounced manner of speaking beloved by video essayists, drama commentators, and DIY experts on the platform. The ur-example cited is usually Hank Green, who’s been making videos on everything from the American health care system to the “Top 10 Freaking Amazing Explosions” since literally 2007.

Actual scholars have attempted to describe what YouTube voice sounds like. Speech pathologist and PhD candidate Erin Hall told Vice that there are two things happening here: “One is the actual segments they’re using — the vowels and consonants. They’re over-enunciating compared to casual speech, which is something newscasters or radio personalities do.” Second: “They’re trying to keep it more casual, even if what they’re saying is standard, adding a different kind of intonation makes it more engaging to listen to.”

In an investigation into YouTube voice, the Atlantic drew from several linguists to determine what specific qualities this manner of speaking shares. Essentially, it’s all about pronunciation and pacing. On camera, it takes more effort to keep someone interested (see also: exaggerated hand and facial motions). “Changing of pacing — that gets your attention,” said linguistics professor Naomi Baron. Baron noted that YouTubers tended to overstress both vowels and consonants, such as someone saying “exactly” like “eh-ckzACKTly.” She guesses that the style stems in part from informal news broadcast programs or “infotainment” like The Daily Show. Another, Mark Liberman of the University of Pennsylvania, put it bluntly: It’s “intellectual used-car-salesman voice,” he wrote. He also compared it to a carnival barker. (...)

Last week a TikTok came on my For You page that explored digital accents. TikToker @Averybrynn was referringspecifically to what she called the “beauty YouTuber dialect,” which she described as “like they weirdly pronounce everything just a little bit too much in these small little snippets?” What makes it distinct from regular YouTube voice is that each word tends to be longer than it should, while also being bookended by a staccato pause. There’s also a common inclination to turn short vowels into long vowels, like saying “thee” instead of “the.” Others in the comments pointed out the repeated use of the first person plural when referring to themselves (“and now we’re gonna go in with a swipe of mascara”), while one linguistics major noted that this was in fact a “sociolect,” not a dialect, because it refers to a social group.

It’s the sort of speech typically associated with female influencers who, by virtue of the job, we assume are there to endear themselves to the audience or present a trustworthy sales pitch. But what’s most interesting to watch about YouTube voice and the influencer accent is how normal people have adapted to it in their own, regular-person TikTok videos and Instagram stories. If you listen closely to enough people’s front-facing camera videos, you’ll hear a voice that sounds somewhere between a TED Talk and sponsored content, perhaps even within your own social circles. Is this a sign that as influencer culture bleeds into our everyday lives, many of the quirks that professionals use will become normal for us too? Maybe! Is it a sign that social platforms are turning us all into salespeople? Also maybe!

But here’s the question I haven’t heard anyone ask yet: If everyone finds these ways of speaking annoying to some degree, then how should people actually talk into the camera?

by Rebecca Jennings, Vox | Read more:

Image: YouTube/Anyone Can Play Guitar

[ed. Got the link for this article from one of my top three favorite online guitar instructors: Adrian Woodward, who normally sounds like a cross between Alfred Hitchcock and the Geico gecko. Here he tries a YouTube voice for fun. If you're a guitar player, do check out his instruction videos on YouTube at Anyone Can Play Guitar. High quality, and great dry personality.]

Friday, August 20, 2021

Tony Joe White - Behind the Music

[ed. Part 2 here. Been trying to learn some Tony Joe White guitar style lately. Great technique. If you're unfamiliar with him, or only know Rainy Night in Georgia and Polk Salad Annie, check out some of his other stuff on YouTube like this, this, this, and this whole album (Closer to the Truth). I love the story about Tina Turner recording a few of his songs. Starts at 30:25 - 34:30, and how he got into songwriting at 13:40 - 16:08.]

Thursday, August 5, 2021

American Gentry

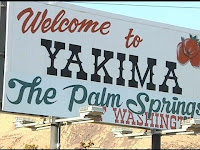

For the first eighteen years of my life, I lived in the very center of Washington state, in a city called Yakima. Shout-out to the self-proclaimed Palm Springs of Washington!

Yakima is a place I loved dearly and have returned to often over the years since, but I’ve never lived there again on a permanent basis. The same was true of most of my close classmates in high school: If they had left for college, most had never returned for longer than a few months at a time. Practically all of them now lived in major metro areas scattered across the country, not our hometown with its population of 90,000.

There were a lot of talented and interesting people in that group, most of whom I had more or less lost touch with over the intervening years. A few years ago, I had the idea of interviewing them to ask precisely why they haven’t come back and how they felt about it. That piece never really came together, but it was fascinating talking to a bunch of folks I hadn’t spoken to in years regarding what they thought and how they felt about home.

For the most part, their answers to my questions revolved around work. Few bore our hometown much, if any, ill will; they’d simply gone away to college, many had gone to graduate school after that, and the kinds of jobs they were now qualified for didn’t really exist in Yakima. Its economy revolved then, and revolves to an ever greater extent now, around commercial agriculture. There are other employers, but not much demand for highly educated professionals - which is generally what my high-achieving classmates became - relative to a larger city.

The careers they ended up pursuing, in corporate or management consulting, non-profits, finance, media, documentary filmmaking, and the like, exist to a much greater degree in major metropolitan areas. There are a few in Portland, and others in New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Austin, and me in Phoenix. A great many of my former classmates live in Seattle. We were lucky that one of the country’s most booming major metros, with the most highly educated Millennial population in the country, is 140 miles away from where we grew up on the other side of the Cascade Mountains: close in absolute terms, but a world away culturally, economically, and politically.

Only a few have returned to Yakima permanently after their time away. Those who have seem to like it well enough; for a person lucky and accomplished enough to get one of those reasonably affluent professional jobs, Yakima - like most cities in the US - isn’t a bad place to live. The professional-managerial class, and the older Millennials in the process of joining it, has a pretty excellent material standard of living regardless of precisely where they’re at.

But very few of my classmates really belonged to the area’s elite. It wasn’t a city of international oligarchs, but one dominated by its wealthy, largely agricultural property-owning class. They mostly owned, and still own, fruit companies: apples, cherries, peaches, and now hops and wine-grapes. The other large-scale industries in the region, particularly commercial construction, revolve at a fundamental level around agriculture: They pave the roads on which fruits and vegetables are transported to transshipment points, build the warehouses where the produce is stored, and so on.

Commercial agriculture is a lucrative industry, at least for those who own the orchards, cold storage units, processing facilities, and the large businesses that cater to them. They have a trusted and reasonably well-paid cadre of managers and specialists in law, finance, and the like - members of the educated professional-managerial class that my close classmates and I have joined - but the vast majority of their employees are lower-wage laborers. The owners are mostly white; the laborers are mostly Latino, a significant portion of them undocumented immigrants. Ownership of the real, core assets is where the region’s wealth comes from, and it doesn’t extend down the social hierarchy. Yet this bounty is enough to produce hilltop mansions, a few high-end restaurants, and a staggering array of expensive vacation homes in Hawaii, Palm Springs, and the San Juan Islands.

This class of people exists all over the United States, not just in Yakima. So do mid-sized metropolitan areas, the places where huge numbers of Americans live but which don’t figure prominently in the country’s popular imagination or its political narratives: San Luis Obispo, California; Odessa, Texas; Bloomington, Illinois; Medford, Oregon; Hilo, Hawaii; Dothan, Alabama; Green Bay, Wisconsin. (As an aside, part of the reason I loved Parks and Recreation was because it accurately portrayed life in a place like this: a city that wasn’t small, which served as the hub for a dispersed rural area, but which wasn’t tightly connected to a major metropolitan area.)

This kind of elite’s wealth derives not from their salary - this is what separates them from even extremely prosperous members of the professional-managerial class, like doctors and lawyers - but from their ownership of assets. Those assets vary depending on where in the country we’re talking about; they could be a bunch of McDonald’s franchises in Jackson, Mississippi, a beef-processing plant in Lubbock, Texas, a construction company in Billings, Montana, commercial properties in Portland, Maine, or a car dealership in western North Carolina. Even the less prosperous parts of the United States generate enough surplus to produce a class of wealthy people. Depending on the political culture and institutions of a locality or region, this elite class might wield more or less political power. In some places, they have an effective stranglehold over what gets done; in others, they’re important but not all-powerful.

Wherever they live, their wealth and connections make them influential forces within local society. In the aggregate, through their political donations and positions within their localities and regions, they wield a great deal of political influence. They’re the local gentry of the United States.

(Yes, that’s a real sign. It’s one of the few things outsiders tend to remember about Yakima, along with excellent cheeseburgers from Miner’s and one of the nation’s worst COVID-19 outbreaks.)

Yakima is a place I loved dearly and have returned to often over the years since, but I’ve never lived there again on a permanent basis. The same was true of most of my close classmates in high school: If they had left for college, most had never returned for longer than a few months at a time. Practically all of them now lived in major metro areas scattered across the country, not our hometown with its population of 90,000.

There were a lot of talented and interesting people in that group, most of whom I had more or less lost touch with over the intervening years. A few years ago, I had the idea of interviewing them to ask precisely why they haven’t come back and how they felt about it. That piece never really came together, but it was fascinating talking to a bunch of folks I hadn’t spoken to in years regarding what they thought and how they felt about home.

For the most part, their answers to my questions revolved around work. Few bore our hometown much, if any, ill will; they’d simply gone away to college, many had gone to graduate school after that, and the kinds of jobs they were now qualified for didn’t really exist in Yakima. Its economy revolved then, and revolves to an ever greater extent now, around commercial agriculture. There are other employers, but not much demand for highly educated professionals - which is generally what my high-achieving classmates became - relative to a larger city.

The careers they ended up pursuing, in corporate or management consulting, non-profits, finance, media, documentary filmmaking, and the like, exist to a much greater degree in major metropolitan areas. There are a few in Portland, and others in New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Austin, and me in Phoenix. A great many of my former classmates live in Seattle. We were lucky that one of the country’s most booming major metros, with the most highly educated Millennial population in the country, is 140 miles away from where we grew up on the other side of the Cascade Mountains: close in absolute terms, but a world away culturally, economically, and politically.

Only a few have returned to Yakima permanently after their time away. Those who have seem to like it well enough; for a person lucky and accomplished enough to get one of those reasonably affluent professional jobs, Yakima - like most cities in the US - isn’t a bad place to live. The professional-managerial class, and the older Millennials in the process of joining it, has a pretty excellent material standard of living regardless of precisely where they’re at.

But very few of my classmates really belonged to the area’s elite. It wasn’t a city of international oligarchs, but one dominated by its wealthy, largely agricultural property-owning class. They mostly owned, and still own, fruit companies: apples, cherries, peaches, and now hops and wine-grapes. The other large-scale industries in the region, particularly commercial construction, revolve at a fundamental level around agriculture: They pave the roads on which fruits and vegetables are transported to transshipment points, build the warehouses where the produce is stored, and so on.

Commercial agriculture is a lucrative industry, at least for those who own the orchards, cold storage units, processing facilities, and the large businesses that cater to them. They have a trusted and reasonably well-paid cadre of managers and specialists in law, finance, and the like - members of the educated professional-managerial class that my close classmates and I have joined - but the vast majority of their employees are lower-wage laborers. The owners are mostly white; the laborers are mostly Latino, a significant portion of them undocumented immigrants. Ownership of the real, core assets is where the region’s wealth comes from, and it doesn’t extend down the social hierarchy. Yet this bounty is enough to produce hilltop mansions, a few high-end restaurants, and a staggering array of expensive vacation homes in Hawaii, Palm Springs, and the San Juan Islands.

This class of people exists all over the United States, not just in Yakima. So do mid-sized metropolitan areas, the places where huge numbers of Americans live but which don’t figure prominently in the country’s popular imagination or its political narratives: San Luis Obispo, California; Odessa, Texas; Bloomington, Illinois; Medford, Oregon; Hilo, Hawaii; Dothan, Alabama; Green Bay, Wisconsin. (As an aside, part of the reason I loved Parks and Recreation was because it accurately portrayed life in a place like this: a city that wasn’t small, which served as the hub for a dispersed rural area, but which wasn’t tightly connected to a major metropolitan area.)

This kind of elite’s wealth derives not from their salary - this is what separates them from even extremely prosperous members of the professional-managerial class, like doctors and lawyers - but from their ownership of assets. Those assets vary depending on where in the country we’re talking about; they could be a bunch of McDonald’s franchises in Jackson, Mississippi, a beef-processing plant in Lubbock, Texas, a construction company in Billings, Montana, commercial properties in Portland, Maine, or a car dealership in western North Carolina. Even the less prosperous parts of the United States generate enough surplus to produce a class of wealthy people. Depending on the political culture and institutions of a locality or region, this elite class might wield more or less political power. In some places, they have an effective stranglehold over what gets done; in others, they’re important but not all-powerful.

Wherever they live, their wealth and connections make them influential forces within local society. In the aggregate, through their political donations and positions within their localities and regions, they wield a great deal of political influence. They’re the local gentry of the United States.

by Patrick Wyman, Perspectives: Past, Present, and Future | Read more:

Image: uncredited

[ed. I live 30 miles from Yakima, so this is of some interest.]

Tuesday, May 11, 2021

Is Capitalism Killing Conservatism?

The report Wednesday that U.S. birthrates fell to a record low in 2020 was expected but still grim. On Twitter the news was greeted, characteristically, by conservative laments and liberal comments implying that it’s mostly conservatism’s fault — because American capitalism allegedly makes parenthood unaffordable, work-life balance impossible and atomization inevitable.

This is a specific version of a long-standing argument about the tensions between traditionalism and capitalism, which seems especially relevant now that the right doesn’t know what it’s conserving anymore.

In a recent essay for New York Magazine, for instance, Eric Levitz argues that the social trends American conservatives most dislike — the rise of expressive individualism and the decline of religion, marriage and the family — are driven by socioeconomic forces the right’s free-market doctrines actively encourage. “America’s moral traditionalists are wedded to an economic system that is radically anti-traditional,” he writes, and “Republicans can neither wage war on capitalism nor make peace with its social implications.”

This argument is intuitively compelling. But the historical record is more complex. If the anti-traditional churn of capitalism inevitably doomed religious practice, communal associations or the institution of marriage, you would expect those things to simply decline with rapid growth and swift technological change. Imagine, basically, a Tocquevillian early America of sturdy families, thriving civic life and full-to-bursting pews giving way, through industrialization and suburbanization, to an ever-more-individualistic society.

But that’s not exactly what you see. Instead, as Lyman Stone points out in a recent report for the American Enterprise Institute (where I am a visiting fellow), the Tocquevillian utopia didn’t really yet exist when Alexis de Tocqueville was visiting America in the 1830s. Instead, the growth of American associational life largely happened during the Industrial Revolution. The rise of fraternal societies is a late-19th- and early-20th-century phenomenon. Membership in religious bodies rises across the hypercapitalist Gilded Age. The share of Americans who married before age 35 stayed remarkably stable from the 1890s till the 1960s, through booms and depressions and drastic economic change.

This suggests that social conservatism can be undermined by economic dynamism but also respond dynamically in its turn — through a constant “reinvention of tradition,” you might say, manifested in religious revival, new forms of association, new models of courtship, even as older forms pass away.

It’s only after the 1960s that this conservative reinvention seems to fail, with churches dividing, families failing, associational life dissolving. And capitalist values, the economic and sexual individualism of the neoliberal age, clearly play some role in this change.

But strikingly, after the 1960s, economic dynamism also diminishes as productivity growth drops and economic growth decelerates. So it can’t just be capitalist churn undoing conservatism, exactly, if economic stagnation and social decay go hand in hand.

One small example: Rates of geographic mobility in the United States, which you could interpret as a measure of how capitalism uproots people from their communities, have declined over the last few decades. But this hasn’t somehow preserved rural traditionalism. Quite the opposite: Instead of a rooted and religious heartland, you have more addiction, suicide and anomie.

Or a larger example: Western European nations do more to tame capitalism’s Darwinian side than America, with more regulation and family supports and welfare-state protections. Are their societies more fecund or religious? No, their economic stagnation and demographic decline have often been deeper than our own.

So it’s not that capitalist dynamism inevitably dissolves conservative habits. It’s more that the wealth this dynamism piles up, the liberty it enables and the technological distractions it invents let people live more individualistically — at first happily, with time perhaps less so — in ways that eventually undermine conservatism and dynamism together. At which point the peril isn’t markets red in tooth and claw, but a capitalist endgame that resembles Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World,” with a rich and technologically proficient world turning sterile and dystopian.

This is a specific version of a long-standing argument about the tensions between traditionalism and capitalism, which seems especially relevant now that the right doesn’t know what it’s conserving anymore.

In a recent essay for New York Magazine, for instance, Eric Levitz argues that the social trends American conservatives most dislike — the rise of expressive individualism and the decline of religion, marriage and the family — are driven by socioeconomic forces the right’s free-market doctrines actively encourage. “America’s moral traditionalists are wedded to an economic system that is radically anti-traditional,” he writes, and “Republicans can neither wage war on capitalism nor make peace with its social implications.”

This argument is intuitively compelling. But the historical record is more complex. If the anti-traditional churn of capitalism inevitably doomed religious practice, communal associations or the institution of marriage, you would expect those things to simply decline with rapid growth and swift technological change. Imagine, basically, a Tocquevillian early America of sturdy families, thriving civic life and full-to-bursting pews giving way, through industrialization and suburbanization, to an ever-more-individualistic society.

But that’s not exactly what you see. Instead, as Lyman Stone points out in a recent report for the American Enterprise Institute (where I am a visiting fellow), the Tocquevillian utopia didn’t really yet exist when Alexis de Tocqueville was visiting America in the 1830s. Instead, the growth of American associational life largely happened during the Industrial Revolution. The rise of fraternal societies is a late-19th- and early-20th-century phenomenon. Membership in religious bodies rises across the hypercapitalist Gilded Age. The share of Americans who married before age 35 stayed remarkably stable from the 1890s till the 1960s, through booms and depressions and drastic economic change.

This suggests that social conservatism can be undermined by economic dynamism but also respond dynamically in its turn — through a constant “reinvention of tradition,” you might say, manifested in religious revival, new forms of association, new models of courtship, even as older forms pass away.

It’s only after the 1960s that this conservative reinvention seems to fail, with churches dividing, families failing, associational life dissolving. And capitalist values, the economic and sexual individualism of the neoliberal age, clearly play some role in this change.

But strikingly, after the 1960s, economic dynamism also diminishes as productivity growth drops and economic growth decelerates. So it can’t just be capitalist churn undoing conservatism, exactly, if economic stagnation and social decay go hand in hand.

One small example: Rates of geographic mobility in the United States, which you could interpret as a measure of how capitalism uproots people from their communities, have declined over the last few decades. But this hasn’t somehow preserved rural traditionalism. Quite the opposite: Instead of a rooted and religious heartland, you have more addiction, suicide and anomie.

Or a larger example: Western European nations do more to tame capitalism’s Darwinian side than America, with more regulation and family supports and welfare-state protections. Are their societies more fecund or religious? No, their economic stagnation and demographic decline have often been deeper than our own.

So it’s not that capitalist dynamism inevitably dissolves conservative habits. It’s more that the wealth this dynamism piles up, the liberty it enables and the technological distractions it invents let people live more individualistically — at first happily, with time perhaps less so — in ways that eventually undermine conservatism and dynamism together. At which point the peril isn’t markets red in tooth and claw, but a capitalist endgame that resembles Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World,” with a rich and technologically proficient world turning sterile and dystopian.

by Ross Douthat, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Carlos Javier Ortiz/Redux

Monday, May 10, 2021

The Truth about Painkillers

In October 2003, the Orlando Sentinel published "OxyContin under Fire," a five-part series that profiled several "accidental addicts" — individuals who were treated for pain and wound up addicted to opioids. They "put their faith in their doctors and ended up dead, or broken" the Sentinel wrote of these victims. Among them were a 36-year-old computer-company executive from Tampa and a 39-year-old Kissimmee handyman and father of three — the latter of whom died of an overdose.

The Sentinel series helped set the template for what was to become the customary narrative for reporting on the opioid crisis. Social worker Brooke Feldman called attention to the prototype in 2017:

Indeed, four months after the original "OxyContin under Fire" story ran, the paper issued a correction: Both the handyman and the executive were heavily involved with drugs before their doctors ever prescribed OxyContin. Like Feldman, neither man was an accidental addict.

Yet one cannot overstate the media's continued devotion to the narrative, as Temple University journalism professor Jillian Bauer-Reese can attest. Soon after she created an online repository of opioid recovery stories, reporters began calling her, making very specific requests. "They were looking for people who had started on a prescription from a doctor or a dentist," she told the Columbia Journalism Review. "They had essentially identified a story that they wanted to tell and were looking for a character who could tell that story."

The story, of course, was the one about the accidental addict. But to what purpose?

Some reporters, no doubt, simply hoped to call attention to the opioid epidemic by showcasing sympathetic and relatable individuals — victims who started out as people like you and me. It wouldn't be surprising if drug users or their loved ones, aware that a victim-infused narrative would dilute the stigma that comes with addiction, had handed reporters a contrived plotline themselves.

Another theory — perhaps too cynical, perhaps not cynical enough — is that the accidental-addict trope was irresistible to journalists in an elite media generally unfriendly to Big Pharma. Predisposed to casting drug companies as the sole villain in the opioid epidemic, they seized on the story of the accidental addict as an object lesson in what happens when greedy companies push a product that is so supremely addictive, it can hook anyone it's prescribed to.

Whatever the media's motives, the narrative does not fit with what we've learned over two decades since the opioid crisis began. We know now that the vast majority of patients who take pain relievers like oxycodone and hydrocodone never get addicted. We also know that people who develop problems are very likely to have struggled with addiction, or to be suffering from psychological trouble, prior to receiving opioids. Furthermore, we know that individuals who regularly misuse pain relievers are far more likely to keep obtaining them from illicit sources rather than from their own doctors.

In short, although accidental addiction can happen, otherwise happy lives rarely come undone after a trip to the dental surgeon. And yet the exaggerated risk from prescription opioids — disseminated in the media but also advanced by some vocal physicians — led to an overzealous regime of pill control that has upended the lives of those suffering from real pain.

To be sure, some restrictions were warranted. Too many doctors had prescribed opioids far too liberally for far too long. But tackling the problem required a scalpel, not the machete that health authorities, lawmakers, health-care systems, and insurers ultimately wielded, barely distinguishing between patients who needed opioids for deliverance from disabling pain and those who sought pills for recreation or profit, or to maintain a drug habit.

The parable of the accidental addict has resulted in consequences that, though unintended, have been remarkably destructive. Fortunately, a peaceable co-existence between judicious pain treatment, the curbing of pill diversion, and the protection of vulnerable patients against abuse and addiction is possible, as long as policymakers, physicians, and other authorities are willing to take the necessary steps. (...)

Many physicians... began refusing to prescribe opioids and withdrawing patients from their stable opioid regimens around 2011 — approximately the same time as states launched their reform efforts. Reports of pharmacies declining to fill prescriptions — even for patients with terminal illness, cancer pain, or acute post-surgical pain — started surfacing. At that point, 10 million Americans were suffering "high impact pain," with four in five being unable to work and a third no longer able to perform basic self-care tasks such as washing themselves and getting dressed.

Their prospects grew even more tenuous with the release of the CDC's "Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain" in 2016. The guideline, which was labeled non-binding, offered reasonable advice to primary-care doctors — for example, it recommended going slow when initiating doses and advised weighing the harms and benefits of opioids. It also imposed no cap on dosage, instead advising prescribers to "avoid increasing dosage to ≥90 MME per day." (An MME, or morphine milligram equivalent, is a basic measure of opioid potency relative to morphine: A 15 mg tablet of morphine equals 15 MMEs; 15 mg of oxycodone converts to about 25 mg morphine.)

Yet almost overnight, the CDC guideline became a new justification for dose control, with the 90 MME threshold taking on the power of an enforceable national standard. Policymakers, insurers, health-care systems, quality-assurance agencies, pharmacies, Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers, contractors for the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and state health authorities alike employed 90 MME as either a strict daily limit or a soft goal — the latter indicating that although exceptions were possible, they could be made only after much paperwork and delay.

As a result, prescribing fell even more sharply, in terms of both dosages per capita and numbers of prescriptions written. A 2019 Quest Diagnostics survey of 500 primary-care physicians found that over 80% were reluctant to accept patients who were taking prescription opioids, while a 2018 survey of 219 primary-care clinics in Michigan found that 41% of physicians would not prescribe opioids for patients who weren't already receiving them. Pain specialists, too, were cutting back: According to a 2019 survey conducted by the American Board of Pain Medicine, 72% said they or their patients had been required to reduce the quantity or dose of medication. In the words of Dr. Sean Mackey, director of Stanford University's pain-management program, "[t]here's almost a McCarthyism on this, that's silencing so many [health professionals] who are simply scared."

The Sentinel series helped set the template for what was to become the customary narrative for reporting on the opioid crisis. Social worker Brooke Feldman called attention to the prototype in 2017: