[ed. The Squarespace ad didn't seem to make much sense, but the teaser was quite fun (expand).]

Tuesday, February 14, 2023

Super Bowl Ads: Hit and Miss

Super Bowl commercials, from Adam Driver(s) to M&M candies; the hits and the misses (NPR)

Monday, February 13, 2023

The State of the Culture (2023)

It’s boom times in culture, my friends...

Hey, don’t look at me that way—it really is boom times. At least the numbers are huge:

The metrics for our culture have never been. . . well, they’ve never been larger.

Hey, don’t look at me that way—it really is boom times. At least the numbers are huge:

- A hundred thousand songs are uploaded daily to streaming platforms.

- In the last year 1.7 million books were self-published.

- 2,500 videos are uploaded to YouTube each minute.

- There are now 3 million podcasts—and 30 million podcast episodes were released last year.

- 86% of youngsters want to grow up to become influencers, and contribute to these impressive numbers

The metrics for our culture have never been. . . well, they’ve never been larger.

And that’s just what the humans do. We’ve got to add in all the robot stuff, too. We now have music, writing, and visual art from artificial intelligence—and it can create a theoretically infinite number of works.Everybody can have their own theme song. Or get a custom-made poem from ChatGPT. Or if you want a painting of Drake in the style of Rembrandt, AI can deliver that too.

Our culture is one of abundance and instantaneous gratification.

Never before has so much culture been available to so many at such little cost.

There’s just one tiny problem.

Where’s the audience? The supply of culture is HUGE and GROWING. But the demand side of the equation is ugly.

In many cases—newspaper subscribers, album purchases, movie tickets sold, etc.—the metrics have been shrinking or even collapsing.

For books to flourish, for example, you need a culture that promotes reading. But most people happily live without those reprocessed trees. As a result, only 28 books sold more than 500,000 copies last year—and eight of them were by the same romance writer.

But let’s turn around and look at those folks in the audience. It’s sobering to see what they’re actually doing. Consumers of culture have so many options to choose from—so what do they pick?

The brutal truth is that there’s an ocean of stuff out there, but consumers sip it with a narrow straw.

You can tell a lot about the future by looking at teenagers. What that data tells us is that they pick a web platform—often only one—and it becomes their prism for evaluating the entire world.

One of the big winners here is YouTube. It’s so pervasive that we may soon need 12-step programs for YouTube addicts.

The brutal truth is that there’s an ocean of stuff out there, but consumers sip it with a narrow straw.

You can tell a lot about the future by looking at teenagers. What that data tells us is that they pick a web platform—often only one—and it becomes their prism for evaluating the entire world.

One of the big winners here is YouTube. It’s so pervasive that we may soon need 12-step programs for YouTube addicts.

TikTok is the other “narrow straw” in today’s culture—and this is especially troubling. TikTok turns everything into bite-sized candy. Surveys reveal that teens embrace it primarily for its comic and zany attributes, and the rule for success on the platform is to “make your TikToks as short as possible.”

What happens if an entire generation ignores newspapers, periodicals, and books—and other boring things like friends and relationships—in order to experience the world and its cultural offerings in this infantilizing context?

We have to deal with this audience, whether we like it or not. That’s the crucial demand side of the equation. There’s surely no shortage of songs or articles or podcasts, so let’s focus our efforts on creating a discerning audience for these offerings. A more culturally savvy citizen is not just good business for the arts world, but it’s also healthy for society.

But who will undertake this vital project?

by Ted Gioia, The Honest Broker | Read more:

Images: Twitter

Labels:

Business,

Culture,

Economics,

Media,

Technology

China’s Top Airship Scientist Promoted Program to Watch the World from Above

In 2019, years before a hulking high-altitude Chinese balloon floated across the United States and caused widespread alarm, one of China’s top aeronautics scientists made a proud announcement that received little attention back then: His team had launched an airship more than 60,000 feet into the air and sent it sailing around most of the globe, including across North America.

The scientist, Wu Zhe, told a state-run news outlet at the time that the “Cloud Chaser” airship was a milestone in his vision of populating the upper reaches of the earth’s atmosphere with steerable balloons that could be used to provide early warnings of natural disasters, monitor pollution or carry out airborne surveillance. (...)

Chinese strategists see near space as an arena of deepening great-power rivalry, where China must master the new materials and technologies needed to establish a firm presence, or risk being edged out. That anxiety has deepened as relations with the United States have soured under Xi Jinping, China’s resolutely nationalist leader. Near space, Chinese analysts argue, offers a potentially useful alternative to satellites and surveillance planes, which may become vulnerable to detection, blocking or attacks.

The scientist, Wu Zhe, told a state-run news outlet at the time that the “Cloud Chaser” airship was a milestone in his vision of populating the upper reaches of the earth’s atmosphere with steerable balloons that could be used to provide early warnings of natural disasters, monitor pollution or carry out airborne surveillance. (...)

Professor Wu, who turns 66 this month, has emerged as a central figure in China’s ambitions in “near space,” the band of the atmosphere between 12 and 62 miles above earth that is too high for most planes to stay aloft for long and too low for space satellites. (...)

Chinese strategists see near space as an arena of deepening great-power rivalry, where China must master the new materials and technologies needed to establish a firm presence, or risk being edged out. That anxiety has deepened as relations with the United States have soured under Xi Jinping, China’s resolutely nationalist leader. Near space, Chinese analysts argue, offers a potentially useful alternative to satellites and surveillance planes, which may become vulnerable to detection, blocking or attacks.

Near space “is a major sphere of competition between the 21st century military powers,” Shi Hong, a Chinese military commentator wrote in a current affairs journal last year. “Whoever gains the edge in near space vehicles will be able to win more of the initiative in future wars.” (...)

High-altitude balloons are made of special materials that can cope with the harsh extremes of temperatures and carry loads in thin air. For the balloons to be useful, operators on earth must be able to stay in touch with them across vast distances. Professor Wu’s open academic publications and other reports indicate that he and his scientific collaborators have long studied these challenges. (...)

In 2022, the cached EMAST web pages say, Professor Wu and his team either launched or planned to launch — the Chinese wording on the timing is unclear — three high-altitude balloons in the air at the same time to form an “airborne network.” The ultimate goal, the company said, was to create an airborne signals network in China using stationary balloons floating at least 80,000 feet high.

It likened the planned network to Starlink, the system of small, low-orbiting satellites operated by SpaceX. Starlink has provided communications support to Ukrainian forces fighting Russian invaders. By 2028, EMAST said, it hoped to “complete a global near-space information network,” but did not elaborate on what that meant.

High-altitude balloons are made of special materials that can cope with the harsh extremes of temperatures and carry loads in thin air. For the balloons to be useful, operators on earth must be able to stay in touch with them across vast distances. Professor Wu’s open academic publications and other reports indicate that he and his scientific collaborators have long studied these challenges. (...)

In 2022, the cached EMAST web pages say, Professor Wu and his team either launched or planned to launch — the Chinese wording on the timing is unclear — three high-altitude balloons in the air at the same time to form an “airborne network.” The ultimate goal, the company said, was to create an airborne signals network in China using stationary balloons floating at least 80,000 feet high.

It likened the planned network to Starlink, the system of small, low-orbiting satellites operated by SpaceX. Starlink has provided communications support to Ukrainian forces fighting Russian invaders. By 2028, EMAST said, it hoped to “complete a global near-space information network,” but did not elaborate on what that meant.

by Chris Buckley, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Larry Mayer/The Billings Gazette, via Associated PressSunday, February 12, 2023

Big Play

Fantasy football is America’s most popular made-up sport. Popularized in the early 1990s as a phone-in game called “Pigskin Playoff,” it’s a dorky adjunct to watching professional football. Participants draft imaginary teams of real players from the actual NFL and are awarded points based on the week-to-week performance of the athletes on their roster.

Like comic books, video games, and basically every other geeky pastime, fantasy football has exploded into the mainstream since its humble beginnings. ESPN and the NFL Network now display stats of “fantasy” performances alongside the actual numbers. Some broadcasters even have programming dedicated to the fantasy prospects of various players. Podcasts and YouTube channels mulling weekly fantasy fortunes abound. I like to imagine the real pundits paid to talk about actual football treat their fantasy counterparts much as jocks treat dweebs in high school movies: jamming them into lockers, holding them upside down by their ankles and shaking them for lunch money, administering swirlies in the ESPN men’s room, etc.

Nevertheless, a 2021 survey showed that some forty million Americans play in fantasy football leagues. And this season, I joined their ranks. (...)

As a casual fan of gridiron football—familiar with a few teams and rosters, passably knowledgeable about which teams were good and which were bad—fantasy was a crash course. To be at all competitive, you must acquire a fairly rigorous knowledge of basically every offensive player in the entire league and their whole statistical outlay: from receiving to rushing yards, from completions to ball control (fumbles result in negative points) to their relative risk for injury. Who’s a “stud”? Who’s a “fraud”? Who’s “eating” this week?

For me, this knowledge translated into a deeper appreciation of the game itself. I went from watching one or two matchups to half the calendar. Players I was previously glad to ignore demanded my attention, as they were now members of my fantasy squad. (...)

I became, in due course, a legitimate, even an obsessive, football fan. Meaning that I could more-or-less capably keep up a conversation with other barflies during games without having to excuse myself to men’s room to Google stuff on my telephone. But I still found myself glued to this second screen: impatiently fiddling with the fantasy sports app that was forever open, awaiting a telltale vibration announcing the latest BIG PLAY. Scores became less important to me than moonshot passes, long yardage receptions, forced fumbles and, especially, injuries. Indeed, few things can make or break a fantasy season like the real-world health of your players.

Fantasy football is something of a misnomer. As a cinematic or literary category, fantasy is typically a highly imaginative affair: the province of faeries, dragons, elves, orcs, hobbits, and all manner of goofs and snarks. It is, in other words, unreal, and altogether separate from reality, as it is commonly experienced.

Fantasy sports, however, deal not with the imaginary, but the real. Specifically, the measurable, statistical real. Watch a football game, and you’ll see athletes performing at the apex of human ability, routinely performing physical feats that beggar the belief of the average couch potato. Open your fantasy app, and, in place of such displays, you’ll see a procession of numbers: +0.04 points per yard, +6 for a TD, -1 for an interception. In a given fantasy league, the player who has accumulated the most points at the end of a match wins the week, and the player with the most weekly wins takes the whole season. In their triumph, the multidimensional exploits of professional athletes are flattened into datasets. So: Where’s the “fantasy,” exactly? (...)

It also feels like training wheels for gambling, and many of the early fantasy football concerns—like Draftkings and FanDuel—have since moved into the legal sports betting space, blanketing networks with ads that have successfully normalized what was until recently regarded mostly as a degenerate hobby. The two pastimes have become so entwined that users can now wager specifically on fantasy outcomes: betting not on actual stats or scores, but on the accumulation of points awarded by the fantasy football algorithm. It’s a weird, super-mediation on an already mediated experience, which pushes the viewer further away from the action on the field and rewards them, now even financially, for conceiving of the game and its players as numbers running down a ledger.

For the purveyors of such entertainment, the reward is obvious. Fantasy football alone is valued as a $70 billion industry: that’s more than the GDP of Panama, and puts it not too far behind the global sports betting industry, which has an estimated annual take of nearly $84 billion. For Draftkings, FanDuel, ESPN, other entrants of the Big Play industry, and the NFL itself, keeping viewers locked in stat-land is serious business.

But fantasy is more than just a revenue stream. It practically constitutes its own psychology of football fandom. Participants are asked at once to over-identify with players and to regard them at an even further distance. This strange combination of detachment and hyper-involvement no doubt redounds to the benefit of a league that is increasingly also in the business of rebuffing legitimate criticism.

Because in forcing you to regard these athletes as objects—datasets to be swapped in and out, based on ever-evolving projections and statistical tweaks—fantasy captures precisely how NFL commissioners and owners think of their players.

[ed. Super Bowl weekend. American hype, patriotism, and over-the-top spectacle at its finest (or lowest), not including halftime. Bleh. See also: Downward Spiral (Baffler).

Like comic books, video games, and basically every other geeky pastime, fantasy football has exploded into the mainstream since its humble beginnings. ESPN and the NFL Network now display stats of “fantasy” performances alongside the actual numbers. Some broadcasters even have programming dedicated to the fantasy prospects of various players. Podcasts and YouTube channels mulling weekly fantasy fortunes abound. I like to imagine the real pundits paid to talk about actual football treat their fantasy counterparts much as jocks treat dweebs in high school movies: jamming them into lockers, holding them upside down by their ankles and shaking them for lunch money, administering swirlies in the ESPN men’s room, etc.

Nevertheless, a 2021 survey showed that some forty million Americans play in fantasy football leagues. And this season, I joined their ranks. (...)

As a casual fan of gridiron football—familiar with a few teams and rosters, passably knowledgeable about which teams were good and which were bad—fantasy was a crash course. To be at all competitive, you must acquire a fairly rigorous knowledge of basically every offensive player in the entire league and their whole statistical outlay: from receiving to rushing yards, from completions to ball control (fumbles result in negative points) to their relative risk for injury. Who’s a “stud”? Who’s a “fraud”? Who’s “eating” this week?

For me, this knowledge translated into a deeper appreciation of the game itself. I went from watching one or two matchups to half the calendar. Players I was previously glad to ignore demanded my attention, as they were now members of my fantasy squad. (...)

I became, in due course, a legitimate, even an obsessive, football fan. Meaning that I could more-or-less capably keep up a conversation with other barflies during games without having to excuse myself to men’s room to Google stuff on my telephone. But I still found myself glued to this second screen: impatiently fiddling with the fantasy sports app that was forever open, awaiting a telltale vibration announcing the latest BIG PLAY. Scores became less important to me than moonshot passes, long yardage receptions, forced fumbles and, especially, injuries. Indeed, few things can make or break a fantasy season like the real-world health of your players.

Fantasy football is something of a misnomer. As a cinematic or literary category, fantasy is typically a highly imaginative affair: the province of faeries, dragons, elves, orcs, hobbits, and all manner of goofs and snarks. It is, in other words, unreal, and altogether separate from reality, as it is commonly experienced.

Fantasy sports, however, deal not with the imaginary, but the real. Specifically, the measurable, statistical real. Watch a football game, and you’ll see athletes performing at the apex of human ability, routinely performing physical feats that beggar the belief of the average couch potato. Open your fantasy app, and, in place of such displays, you’ll see a procession of numbers: +0.04 points per yard, +6 for a TD, -1 for an interception. In a given fantasy league, the player who has accumulated the most points at the end of a match wins the week, and the player with the most weekly wins takes the whole season. In their triumph, the multidimensional exploits of professional athletes are flattened into datasets. So: Where’s the “fantasy,” exactly? (...)

It also feels like training wheels for gambling, and many of the early fantasy football concerns—like Draftkings and FanDuel—have since moved into the legal sports betting space, blanketing networks with ads that have successfully normalized what was until recently regarded mostly as a degenerate hobby. The two pastimes have become so entwined that users can now wager specifically on fantasy outcomes: betting not on actual stats or scores, but on the accumulation of points awarded by the fantasy football algorithm. It’s a weird, super-mediation on an already mediated experience, which pushes the viewer further away from the action on the field and rewards them, now even financially, for conceiving of the game and its players as numbers running down a ledger.

For the purveyors of such entertainment, the reward is obvious. Fantasy football alone is valued as a $70 billion industry: that’s more than the GDP of Panama, and puts it not too far behind the global sports betting industry, which has an estimated annual take of nearly $84 billion. For Draftkings, FanDuel, ESPN, other entrants of the Big Play industry, and the NFL itself, keeping viewers locked in stat-land is serious business.

But fantasy is more than just a revenue stream. It practically constitutes its own psychology of football fandom. Participants are asked at once to over-identify with players and to regard them at an even further distance. This strange combination of detachment and hyper-involvement no doubt redounds to the benefit of a league that is increasingly also in the business of rebuffing legitimate criticism.

Because in forcing you to regard these athletes as objects—datasets to be swapped in and out, based on ever-evolving projections and statistical tweaks—fantasy captures precisely how NFL commissioners and owners think of their players.

by John Semley, The Baffler | Read more:

Image: Kelsey Wroten

Saturday, February 11, 2023

The Internationale

[ed. See also: Hard Times; and Sunday Morning Coming Down]

Friday, February 10, 2023

Jon

Back in the time of which I am speaking, due to our Coördinators had mandated us, we had all seen that educational video of "It's Yours to Do With What You Like!" in which teens like ourselfs speak on the healthy benefits of getting off by oneself and doing what one feels like in terms of self-touching, which what we learned from that video was, there is nothing wrong with self-touching, because love is a mystery but the mechanics of love need not be, so go off alone, see what is up, with you and your relation to your own gonads, and the main thing is, just have fun, feeling no shame!

And then nightfall would fall and our facility would fill with the sounds of quiet fast breathing from inside our Privacy Tarps as we all experimented per the techniques taught us in "It's Yours to Do With What You Like!" and what do you suspect, you had better make sure that that little gap between the main wall and the sliding wall that slides out to make your Gender Areas is like really really small. Which guess what, it wasn't.

That is all what I am saying.

And when Josh came back next morning so happy he was crying, that was a further blow to our morality, because why did our Coördinators not catch him on their supposedly nighttime monitors? In all of our hearts was the thought of, O.K., we thought you said no boy-and-girl stuff, and yet here is Josh, with his Old Navy boxers and a hickey on his waist, and none of you guys is even saying boo?

Because I for one wanted to do right, I did not want to sneak through that gap, I wanted to wed someone when old enough (I will soon tell who) and relocate to the appropriate facility in terms of demographics, namely Young Marrieds, such as Scranton, PA, or Mobile, AL, and then along comes Josh doing Ruthie with imperity, and no one is punished, and soon the miracle of birth results and all our Coördinators, even Mr. Delacourt, are bringing Baby Amber stuffed animals? At which point every cell or chromosome or whatever it was in my gonads that had been holding their breaths was suddenly like, Dude, slide through that gap no matter how bad it hurts, squat outside Carolyn's Privacy Tarp whispering, Carolyn, it's me, please un-Velcro your Privacy opening!

Then came the final straw that broke the back of my saying no to my gonads, which was I dreamed I was that black dude on MTV's "Hot and Spicy Christmas" (around like Location Indicator 34412, if you want to check it out) and Carolyn was the oiled-up white chick, and we were trying to earn the Island Vacation by miming through the ten Hot 'n' Nasty Positions before the end of "We Three Kings," only then, sadly, during Her on Top, Thumb in Mouth, her Elf Cap fell off, and as the Loser Buzzer sounded she bent low to me, saying, Oh, Jon, I wish we did not have to do this for fake in front of hundreds of kids on Spring Break doing the wave but instead could do it for real with just each other in private.

And then she kissed me with a kiss I can only describe as melting.

So imagine that is you, you are a healthy young dude who has been self-practicing all those months, and you wake from that dream of a hot chick giving you a melting kiss, and that same hot chick is laying or lying just on the other side of the sliding wall, and meanwhile in the very next Privacy Tarp is that sleeping dude Josh, who a few weeks before a baby was born to the girl he had recently did it with, and nothing bad happened to them, except now Mr. Slippen sometimes let them sleep in.

What would you do?

Well, you would do what I did, you would slip through, and when Carolyn un-Velcroed that Velcro wearing her blue Guess kimono, whispering, Oh my God, I thought you'd never ask, that would be the most romantic thing you had ever underwent.

And though I had many times seen LI 34321 for Honey Grahams, where the stream of milk and the stream of honey enjoin to make that river of sweet-tasting goodness, I did not know that, upon making love, one person may become like the milk and the other like the honey, and soon they cannot even remember who started out the milk and who the honey, they just become one fluid, this like honey/milk combo.

Well, that is what happened to us.

"Teen-agers live in a pristine facility where they want for nothing; their only job is to assess new commercial products. Fed a diet of soothing drugs to keep them happy and productive, they are treated like minor celebrities, with their images depicted on popular trading cards. Moreover, they are fitted with microchips that play advertisements in their heads. These ads substitute for their memories—possibly providing them with better recollections than reality ever could. One of the teen-agers, Jon, falls in love with another, Carolyn, and the couple is soon forced to decide whether to stay in the safe confines of the facility or disconnect their chips and brave the unfamiliar outside world...

And then nightfall would fall and our facility would fill with the sounds of quiet fast breathing from inside our Privacy Tarps as we all experimented per the techniques taught us in "It's Yours to Do With What You Like!" and what do you suspect, you had better make sure that that little gap between the main wall and the sliding wall that slides out to make your Gender Areas is like really really small. Which guess what, it wasn't.

That is all what I am saying.

Also all what I am saying is, who could blame Josh for noting that gap and squeezing through it snakelike in just his Old Navy boxers that Old Navy gave us to wear for gratis, plus who could blame Ruthie for leaving her Velcro knowingly un-Velcroed? Which soon all the rest of us heard them doing what the rest of us so badly wanted to be doing, only we, being more mindful of the rules than them, just laid there doing the self-stuff from the video, listening to Ruth and Josh really doing it for real, which believe me, even that was pretty fun.

And when Josh came back next morning so happy he was crying, that was a further blow to our morality, because why did our Coördinators not catch him on their supposedly nighttime monitors? In all of our hearts was the thought of, O.K., we thought you said no boy-and-girl stuff, and yet here is Josh, with his Old Navy boxers and a hickey on his waist, and none of you guys is even saying boo?

Because I for one wanted to do right, I did not want to sneak through that gap, I wanted to wed someone when old enough (I will soon tell who) and relocate to the appropriate facility in terms of demographics, namely Young Marrieds, such as Scranton, PA, or Mobile, AL, and then along comes Josh doing Ruthie with imperity, and no one is punished, and soon the miracle of birth results and all our Coördinators, even Mr. Delacourt, are bringing Baby Amber stuffed animals? At which point every cell or chromosome or whatever it was in my gonads that had been holding their breaths was suddenly like, Dude, slide through that gap no matter how bad it hurts, squat outside Carolyn's Privacy Tarp whispering, Carolyn, it's me, please un-Velcro your Privacy opening!

Then came the final straw that broke the back of my saying no to my gonads, which was I dreamed I was that black dude on MTV's "Hot and Spicy Christmas" (around like Location Indicator 34412, if you want to check it out) and Carolyn was the oiled-up white chick, and we were trying to earn the Island Vacation by miming through the ten Hot 'n' Nasty Positions before the end of "We Three Kings," only then, sadly, during Her on Top, Thumb in Mouth, her Elf Cap fell off, and as the Loser Buzzer sounded she bent low to me, saying, Oh, Jon, I wish we did not have to do this for fake in front of hundreds of kids on Spring Break doing the wave but instead could do it for real with just each other in private.

And then she kissed me with a kiss I can only describe as melting.

So imagine that is you, you are a healthy young dude who has been self-practicing all those months, and you wake from that dream of a hot chick giving you a melting kiss, and that same hot chick is laying or lying just on the other side of the sliding wall, and meanwhile in the very next Privacy Tarp is that sleeping dude Josh, who a few weeks before a baby was born to the girl he had recently did it with, and nothing bad happened to them, except now Mr. Slippen sometimes let them sleep in.

What would you do?

Well, you would do what I did, you would slip through, and when Carolyn un-Velcroed that Velcro wearing her blue Guess kimono, whispering, Oh my God, I thought you'd never ask, that would be the most romantic thing you had ever underwent.

And though I had many times seen LI 34321 for Honey Grahams, where the stream of milk and the stream of honey enjoin to make that river of sweet-tasting goodness, I did not know that, upon making love, one person may become like the milk and the other like the honey, and soon they cannot even remember who started out the milk and who the honey, they just become one fluid, this like honey/milk combo.

Well, that is what happened to us.

by George Saunders, New Yorker | Read more:

Image: Michael Bevilacqua, “Hii” (detail) / Deitch Projects

[ed. Great writing, but I have to take Saunders' unsettling dystopian stories in small doses. See also: The Semplica-Girl Diaries (New Yorker).]

[ed. Great writing, but I have to take Saunders' unsettling dystopian stories in small doses. See also: The Semplica-Girl Diaries (New Yorker).]

... although “Jon” is a satire about advertising and consumerism, it’s also about the difficulties and challenges of freeing ourselves from prevailing cultural norms. The story explores the price of self-expression—and the ways in which our memories can diminish, or deepen, our present reality." (Letter from the archive - New Yorker)

The Race to Supercharge Cancer-Fighting T Cells

Crystal Mackall remembers her scepticism the first time she heard a talk about a way to engineer T cells to recognize and kill cancer. Sitting in the audience at a 1996 meeting in Germany, the paediatric oncologist turned to the person next to her and said: “No way. That’s too crazy.”

Today, things are different. “I’ve been humbled,” says Mackall, who now works at Stanford University in California developing such cells to treat brain tumours. The US Food and Drug Administration approved the first modified T cells, called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells, to treat a form of leukaemia in 2017. The treatments have become game changers for several cancers. Five similar products have been approved, and more than 20,000 people have received them. A field once driven by a handful of dogged researchers now boasts hundreds of laboratory groups in academia and industry. More than 500 clinical trials are under way, and other approaches are gearing up to jump from lab to clinic as researchers race to refine T-cell designs and extend their capabilities. “This field is going to go way beyond cancer in the years to come,” Mackall predicts.

Advances in genome editing through processes such as CRISPR, and the ability to rewire cells through synthetic biology, have led to increasingly elaborate approaches for modifying and supercharging T cells for therapy. Such techniques are providing tools to counter some of the limitations of current CAR-T therapies, which are expensive to make, can have dangerous side effects, and have so far been successful only against blood cancers. “These techniques have expanded what we’re able to do with CAR strategies,” says Avery Posey, a cancer immunology researcher at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “It will really take this type of technology forward.”

Even so, the challenge of making such a ‘living drug’ from a person’s cells extends beyond complicated designs. Safety and manufacturing problems remain to be addressed for many of the newest candidates. “There’s an explosion of very fancy things, and I think that’s great,” says immunologist Michel Sadelain at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. “But the complexity cannot always be brought as described into a clinical setting.”

Revved up and ready to go

CAR-T therapies capitalize on the activities of T cells, the immune system’s natural hunters that prowl through the body looking for things that don’t belong. Foreign cells, or those infected with a virus, express unusual proteins that serve as a beacon to T cells, some of which release a toxic stew of molecules to destroy the abnormal cells. This search-and-destroy function can also target cancer cells for elimination, but tumours often have ways of disarming the immune system, such as by cloaking abnormal proteins or suppressing T-cell function.

CAR-T cells carry synthetic proteins — the chimeric antigen receptors — that span the cell membrane. On the outside is a structure that functions like an antibody, binding to specific molecules on the surface of some cancer cells. Once that has bound, the portion of the protein inside the cell stimulates T-cell activity, hot-wiring it into action. The result is a tiny, revved-up, cancer-fighting machine.

Today, things are different. “I’ve been humbled,” says Mackall, who now works at Stanford University in California developing such cells to treat brain tumours. The US Food and Drug Administration approved the first modified T cells, called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells, to treat a form of leukaemia in 2017. The treatments have become game changers for several cancers. Five similar products have been approved, and more than 20,000 people have received them. A field once driven by a handful of dogged researchers now boasts hundreds of laboratory groups in academia and industry. More than 500 clinical trials are under way, and other approaches are gearing up to jump from lab to clinic as researchers race to refine T-cell designs and extend their capabilities. “This field is going to go way beyond cancer in the years to come,” Mackall predicts.

Advances in genome editing through processes such as CRISPR, and the ability to rewire cells through synthetic biology, have led to increasingly elaborate approaches for modifying and supercharging T cells for therapy. Such techniques are providing tools to counter some of the limitations of current CAR-T therapies, which are expensive to make, can have dangerous side effects, and have so far been successful only against blood cancers. “These techniques have expanded what we’re able to do with CAR strategies,” says Avery Posey, a cancer immunology researcher at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “It will really take this type of technology forward.”

Even so, the challenge of making such a ‘living drug’ from a person’s cells extends beyond complicated designs. Safety and manufacturing problems remain to be addressed for many of the newest candidates. “There’s an explosion of very fancy things, and I think that’s great,” says immunologist Michel Sadelain at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. “But the complexity cannot always be brought as described into a clinical setting.”

Revved up and ready to go

CAR-T therapies capitalize on the activities of T cells, the immune system’s natural hunters that prowl through the body looking for things that don’t belong. Foreign cells, or those infected with a virus, express unusual proteins that serve as a beacon to T cells, some of which release a toxic stew of molecules to destroy the abnormal cells. This search-and-destroy function can also target cancer cells for elimination, but tumours often have ways of disarming the immune system, such as by cloaking abnormal proteins or suppressing T-cell function.

CAR-T cells carry synthetic proteins — the chimeric antigen receptors — that span the cell membrane. On the outside is a structure that functions like an antibody, binding to specific molecules on the surface of some cancer cells. Once that has bound, the portion of the protein inside the cell stimulates T-cell activity, hot-wiring it into action. The result is a tiny, revved-up, cancer-fighting machine.

[ed. See also: Engineering T cells (GT).]

Thursday, February 9, 2023

Burt Bacharach

(May, 1928 – February, 2023)

The twain very seldom met: if anything, the divide became more pronounced as the 1960s wore on and a cocktail of new technology and new drugs meant the music aimed at teenagers became more adventurous, strange and innovative. Look at the charts from 1966 or 1967 and you’ll find a stark split: Strawberry Fields Forever and Purple Haze versus Engelbert Humperdinck and Ken Dodd’s Tears.

But Burt Bacharach’s music existed somewhere in the middle. He often got lumbered with the term easy listening. You could see why – his own albums, such as 1965’s Hitmaker! or 1967’s Reach Out, tended towards syrupy arrangements and cooing vocal choruses. Usually compilations of songs other performers had already made successful, they seldom showed off his compositions to their best effect. But in reality, the easy listening label was lazy to the point of being nonsensical, not least because – as any musician will tell you – Bacharach’s songs were seldom easy.

No matter how mellifluous the melody, he dealt in changing meters, odd harmonic shifts, umpteen idiosyncrasies that were perhaps the result of Bacharach’s eclectic musical education, which variously took in studying classical music under the French composer Darius Milhaud, listening to bebop musicians in the jazz clubs of New York’s 52nd Street and hanging out with avant-gardist John Cage.

The truth was that no obvious label or category could contain what Bacharach did: his style was once memorably summed up by Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen as Ravel-like harmonies wedded to street soul. He could come up with Magic Moments for Perry Como, but he could also write for the Drifters, Gene Vincent, Chuck Jackson and the Shirelles.

Listen to Herb Alpert’s version of This Guy’s in Love With You. An unbelievably beautiful, lushly orchestrated ballad, introduced to the world via a light entertainment TV special on which Alpert sang it to his wife, it’s the epitome of grownup, sophisticated 60s pop: you can imagine it floating around in the background of a cocktail party entirely populated by people who agreed with James Bond’s assessment that the Beatles were best listened to wearing earmuffs.

Then listen to Love’s 1966 version of My Little Red Book, a song originally recorded by Manfred Mann: it’s raw, distinctly strange garage rock, complete with a pounding, descending riff that inspired Pink Floyd’s even stranger psychedelic opus Interstellar Overdrive. Bacharach wrote them both. He made music that was genuinely sui generis: rock bands could record his songs, so could mum-friendly crooners, so could soul singers and jazz musicians.

by Alexis Petridis, The Guardian | Read more:

Image: Dionne Warwick and Burt Bacharach recording in 1964. Photograph: Mirrorpix/Getty Images

[ed. A master songwriter with an oversized cultural influence. Obituary.]

[ed. A master songwriter with an oversized cultural influence. Obituary.]

Wednesday, February 8, 2023

Obesity in the age of Ozempic

On a beach in San Sebastian, Spain, Aditi Juneja strutted around in the beige sand wearing a red bikini top with colorful bottoms, her mop of curly hair blowing in the breeze. A close friend and travel companion trailed behind snapping photos.

In the years before the Spain trip, Juneja, 32, a lawyer, had put on 50 pounds. She called it the “Fascist 50” — much of it gained during the Trump presidency, when her work dealt with the era’s democracy abuses.

Diagnosed with clinical obesity, she had come to embrace her larger body size. She’d been steeping herself in literature on fat acceptance and learning about the “Health at Every Size” movement, which seeks to demedicalize obesity and promote an understanding that body size is not necessarily correlated with health. On that beach day, she remembers wanting to document how far she’d come, “to celebrate this beautiful body.”

But around the same time, she was also coming to terms with health issues related to her weight. “I was experiencing the physical effects of being in a heavier body,” she says. First there were pain and mobility issues: Her back was regularly going out, and she was frequently rolling over her ankles.

Then she learned that her cholesterol levels had soared to 10 times the normal range. It was the result of a genetic predisposition and had to be treated by cholesterol medication, her doctor told her, but weight loss could help, too. Juneja was also growing concerned about how her weight would heighten her risk of Type 2 diabetes, for which she has a strong family history, and potentially complicate a future pregnancy.

When her doctor broached medication to treat the obesity — such as semaglutide, currently sold by Novo Nordisk under the brand names Wegovy and Ozempic — Juneja refused. The fat acceptance literature she’d been studying opposed weight loss as a means to health. Using an obesity drug also felt like an admission that her body was something to be ashamed about at a moment when she’d come to embrace it.

The new class of obesity drugs — referred to as “GLP-1-based,” since they contain synthetic versions of the human hormone glucagon-like peptide-1 — are considered the most powerful ever marketed for weight loss. Since the US Food and Drug Administration approved Wegovy for patients with obesity in 2021, buzz on social media and in Hollywood’s gossip mills has erupted, helping drive a surge in popularity that’s contributed to ongoing supply shortages. While celebrities and billionaires such as Elon Musk and Michael Rubin praise the weight loss effects of these drugs, regular patients, including those with Type 2 diabetes, struggle with access, raising questions about who will really benefit from treatment.

But there’s another tension that’s emerged in the GLP-1 story: The medicines have become a lightning rod in an obesity conversation that is increasingly binary — swinging between fat acceptance and fatphobia.

“It feels like you have to be like, ‘I love being fat, this is my fat body,’ or, ‘Fat people are evil,’” Juneja told me.

While many clinicians and researchers hail GLP-1-based therapy as a “breakthrough,” and one deemed safe and effective by FDA, critics question its safety and usefulness. They argue the drugs unnecessarily medicalize obesity and dispute that it’s an illness in need of treatment at all. They also say the medicines perpetuate a dangerous diet culture that idealizes thinness and weight loss at all costs.

At the same time, many of the patients currently on treatment tell a story that seems to fall somewhere between “miracle” and “useless” diet drugs. Despite all the TikTok videos decrying obesity medication as the easy way out, progress is not always straightforward. Navigating side effects, dosing, weight plateaus, and access issues are frustrating features of many patients’ journeys. Patients also told me it’s hard to know if and when to come off the drugs, or that a healthy end goal has been reached. A minority don’t respond to the drugs at all.

One thing they had in common: wanting medical help to lose weight, despite the cultural conversation around fat acceptance. Even Juneja, who eventually started using the GLP-1-based drug tirzepatide, sold as Mounjaro by Eli Lilly, argues that the medicines are part of a more nuanced story, one society needs to internalize. Rather than viewing obesity as the result of personal failing or emotional issues, easily reversed with diet and exercise, patients like Juneja say they’re beginning to see it as medical researchers long have: as a condition that arises from complex interactions between our biology and our environments. Like other complex illnesses, such as diabetes, this means it can also benefit from medical treatment.

And some patients, including those who accept their larger bodies, may want to try obesity medication for help losing weight. “You can be healthy at every size,” Juneja summed up. But “I was not healthy at the size that I was.”

by Julia Belluz, Vox | Read more:

Image: Sargam Gupta for Vox

[ed. See also: The New Obesity Breakthrough Drugs (Ground Truths).]

In the years before the Spain trip, Juneja, 32, a lawyer, had put on 50 pounds. She called it the “Fascist 50” — much of it gained during the Trump presidency, when her work dealt with the era’s democracy abuses.

Diagnosed with clinical obesity, she had come to embrace her larger body size. She’d been steeping herself in literature on fat acceptance and learning about the “Health at Every Size” movement, which seeks to demedicalize obesity and promote an understanding that body size is not necessarily correlated with health. On that beach day, she remembers wanting to document how far she’d come, “to celebrate this beautiful body.”

But around the same time, she was also coming to terms with health issues related to her weight. “I was experiencing the physical effects of being in a heavier body,” she says. First there were pain and mobility issues: Her back was regularly going out, and she was frequently rolling over her ankles.

Then she learned that her cholesterol levels had soared to 10 times the normal range. It was the result of a genetic predisposition and had to be treated by cholesterol medication, her doctor told her, but weight loss could help, too. Juneja was also growing concerned about how her weight would heighten her risk of Type 2 diabetes, for which she has a strong family history, and potentially complicate a future pregnancy.

When her doctor broached medication to treat the obesity — such as semaglutide, currently sold by Novo Nordisk under the brand names Wegovy and Ozempic — Juneja refused. The fat acceptance literature she’d been studying opposed weight loss as a means to health. Using an obesity drug also felt like an admission that her body was something to be ashamed about at a moment when she’d come to embrace it.

The new class of obesity drugs — referred to as “GLP-1-based,” since they contain synthetic versions of the human hormone glucagon-like peptide-1 — are considered the most powerful ever marketed for weight loss. Since the US Food and Drug Administration approved Wegovy for patients with obesity in 2021, buzz on social media and in Hollywood’s gossip mills has erupted, helping drive a surge in popularity that’s contributed to ongoing supply shortages. While celebrities and billionaires such as Elon Musk and Michael Rubin praise the weight loss effects of these drugs, regular patients, including those with Type 2 diabetes, struggle with access, raising questions about who will really benefit from treatment.

But there’s another tension that’s emerged in the GLP-1 story: The medicines have become a lightning rod in an obesity conversation that is increasingly binary — swinging between fat acceptance and fatphobia.

“It feels like you have to be like, ‘I love being fat, this is my fat body,’ or, ‘Fat people are evil,’” Juneja told me.

While many clinicians and researchers hail GLP-1-based therapy as a “breakthrough,” and one deemed safe and effective by FDA, critics question its safety and usefulness. They argue the drugs unnecessarily medicalize obesity and dispute that it’s an illness in need of treatment at all. They also say the medicines perpetuate a dangerous diet culture that idealizes thinness and weight loss at all costs.

At the same time, many of the patients currently on treatment tell a story that seems to fall somewhere between “miracle” and “useless” diet drugs. Despite all the TikTok videos decrying obesity medication as the easy way out, progress is not always straightforward. Navigating side effects, dosing, weight plateaus, and access issues are frustrating features of many patients’ journeys. Patients also told me it’s hard to know if and when to come off the drugs, or that a healthy end goal has been reached. A minority don’t respond to the drugs at all.

One thing they had in common: wanting medical help to lose weight, despite the cultural conversation around fat acceptance. Even Juneja, who eventually started using the GLP-1-based drug tirzepatide, sold as Mounjaro by Eli Lilly, argues that the medicines are part of a more nuanced story, one society needs to internalize. Rather than viewing obesity as the result of personal failing or emotional issues, easily reversed with diet and exercise, patients like Juneja say they’re beginning to see it as medical researchers long have: as a condition that arises from complex interactions between our biology and our environments. Like other complex illnesses, such as diabetes, this means it can also benefit from medical treatment.

And some patients, including those who accept their larger bodies, may want to try obesity medication for help losing weight. “You can be healthy at every size,” Juneja summed up. But “I was not healthy at the size that I was.”

by Julia Belluz, Vox | Read more:

Image: Sargam Gupta for Vox

[ed. See also: The New Obesity Breakthrough Drugs (Ground Truths).]

Labels:

Culture,

Drugs,

Health,

Medicine,

Psychology,

Relationships,

Technology

When M.D. is a Machine Doctor

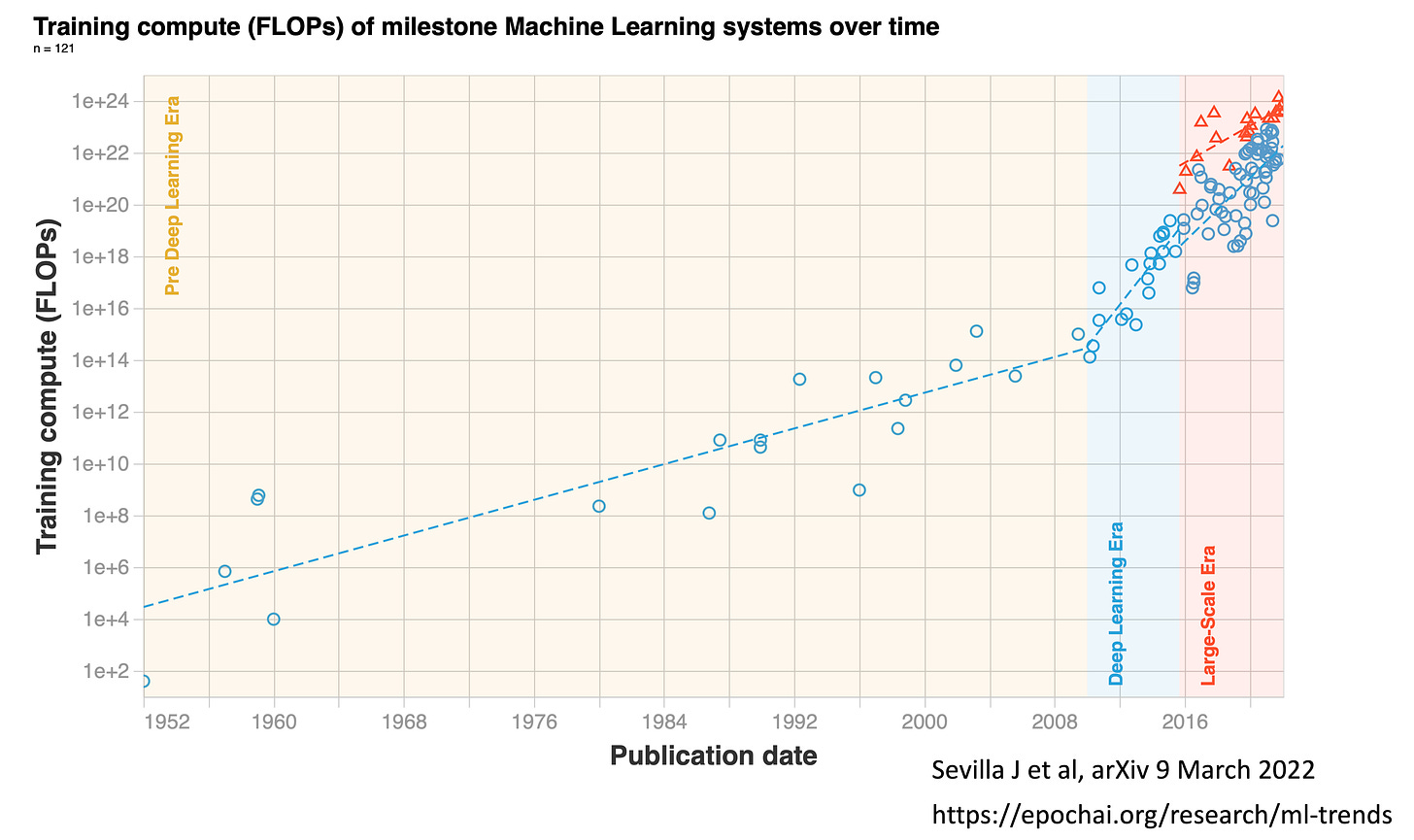

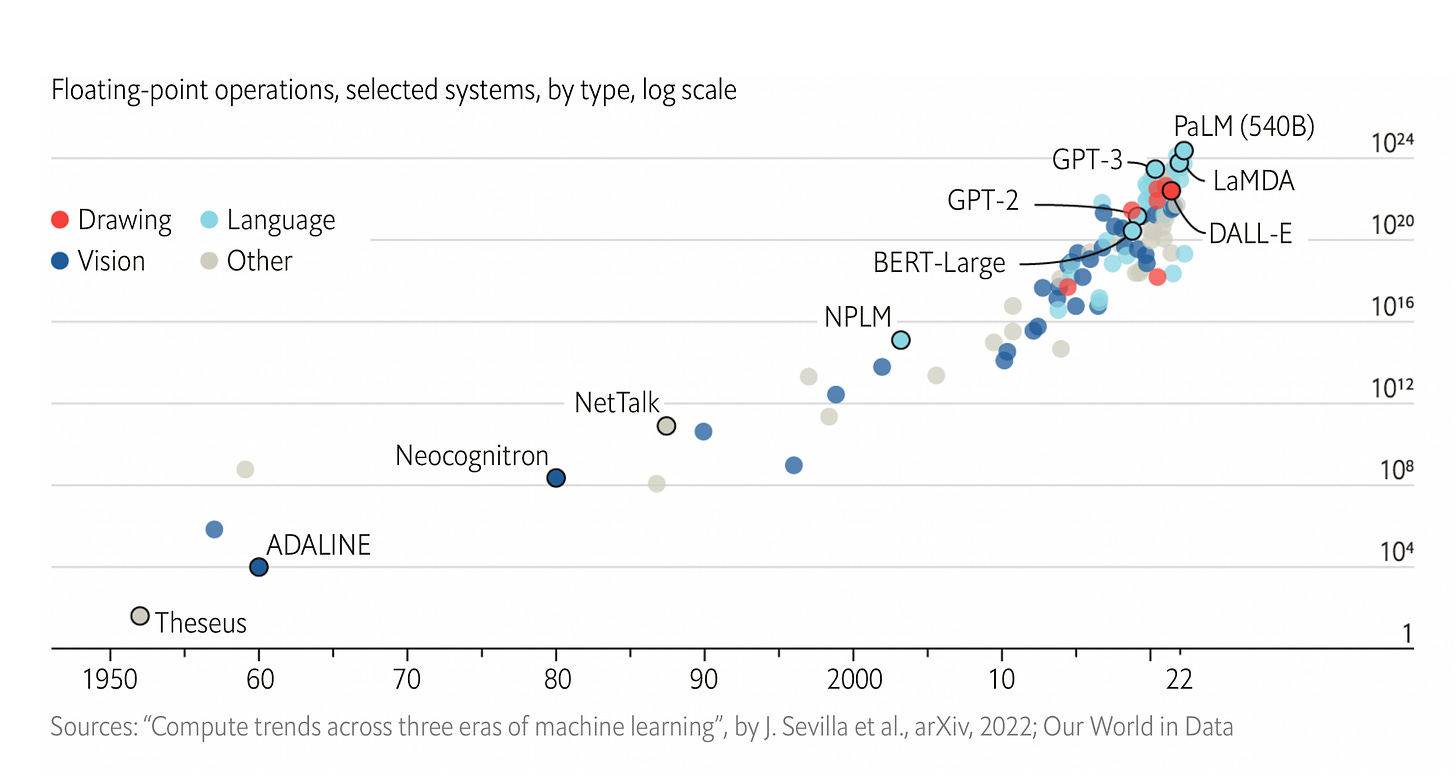

Back in 2019, I wrote Deep Medicine, a book centered on the role that deep learning will have on transforming medicine, which until now has largely been circumscribed to automated interpretation of medical images. Now, four years later, the AI world has charged ahead with large language models (LLMs), dubbed “foundation models” by Stanford HAI’s Percy Liang and colleagues (a 219-page preprint, the longest I have ever seen), which includes BERT, DALL-E, GPT-3, LaMDA and a blitz of others, also known by others as generative AI. You can quickly get an appreciation of the “Large-Scale Era” of transformer models from this Figure below by Jaime Sevilla and colleagues. It got started around 2016, with unprecedented levels of computer performance as quantified by floating-point operations per second (FLOPs). Whereas Moore’s Law for nearly 6 decades was characterized by doubling of training computation every 18-24 months, that is now doubling every 6 months in the era of foundation models.

As of 2022, the training computation used has culminated with Google’s PaLM with 2.5 billion petaFLOPs and Minerva with 2.7 billion peta FLOPS. PaLM uses 540 billion parameters, the coefficient applied to the different calculations within the program. BERT, which was created in 2018, had “only” 110 million parameters, which gives you a sense of exponential growth, well seen by the log-plot below . In 2023, there are models that are 10,000 times larger, with over a trillion parameters and a British company Graphcore that aspires to build one that runs more than 500 trillion parameters.

You’ve undoubtedly seen a plethora of articles in the media in recent months with these newfound capabilities from large language models, setting up the ability to go from text to images, text to video, write coherent essays, write code, generate art and films, and many other capabilities that I’ve tried to cull some of these together below. This provides a sense of seamless integration between different types and massive amounts of data. You may recall the flap about the LaMDA foundation model developed at Google—an employee believed it was sentient. (...)

The Power of Foundation Models in Medicine

Until now. the deep learning in healthcare has almost exclusively been unimodal, particularly emphasizing its applicability for all different types of medical images, from X-rays, CT and MRI scans, path slides, to skin lesions, retinal photos, and electrocardiograms. These deep neural networks for medicine have been based on supervised learning from large annotated datasets, solving one task at a time. Typically the results of a model are only valid locally, where the training and validation was performed. It all has a narrow look.

In contrast, foundation models are multimodal, based upon large amounts of unlabeled, diverse data with self-supervised and transfer learning. (For an in-depth review of self-supervised learning, see our recent Nature BME paper). The limited pre-training requirement provides for adaptability, interactivity, expressivity, and creativity, as we’ve seen with ChatGPT, DALL-E, Stable Diffusion and many models outside of healthcare domains. These models are characterized by in-context learning: the ability to perform tasks for which they were never explicitly trained.

Accordingly, going forward, foundation models for medicine provide the potential for a diverse, integration of medical data that includes electronic health records, images, lab values, biologic layers such as the genome and gut microbiome, and social determinants of health. (...)

I should point out that it’s not exactly a clear or rapid path because there is a paucity of large or even massive medical datasets, and the computing power required to run these models is expensive and not widely available. But the opportunity to get to machine-powered, advanced medical reasoning skills, that would come in handy (an understatement) with so many tasks in medical research (above Figure), and patient care, such as generating high-quality reports and notes, providing clinical decision support for doctors or patients, synthesizing all of a patient’s data from multiple sources, dealing with payors for pre-authorization, and so many routine and often burdensome tasks, is more than alluring.

As of 2022, the training computation used has culminated with Google’s PaLM with 2.5 billion petaFLOPs and Minerva with 2.7 billion peta FLOPS. PaLM uses 540 billion parameters, the coefficient applied to the different calculations within the program. BERT, which was created in 2018, had “only” 110 million parameters, which gives you a sense of exponential growth, well seen by the log-plot below . In 2023, there are models that are 10,000 times larger, with over a trillion parameters and a British company Graphcore that aspires to build one that runs more than 500 trillion parameters.

You’ve undoubtedly seen a plethora of articles in the media in recent months with these newfound capabilities from large language models, setting up the ability to go from text to images, text to video, write coherent essays, write code, generate art and films, and many other capabilities that I’ve tried to cull some of these together below. This provides a sense of seamless integration between different types and massive amounts of data. You may recall the flap about the LaMDA foundation model developed at Google—an employee believed it was sentient. (...)

The Power of Foundation Models in Medicine

Until now. the deep learning in healthcare has almost exclusively been unimodal, particularly emphasizing its applicability for all different types of medical images, from X-rays, CT and MRI scans, path slides, to skin lesions, retinal photos, and electrocardiograms. These deep neural networks for medicine have been based on supervised learning from large annotated datasets, solving one task at a time. Typically the results of a model are only valid locally, where the training and validation was performed. It all has a narrow look.

In contrast, foundation models are multimodal, based upon large amounts of unlabeled, diverse data with self-supervised and transfer learning. (For an in-depth review of self-supervised learning, see our recent Nature BME paper). The limited pre-training requirement provides for adaptability, interactivity, expressivity, and creativity, as we’ve seen with ChatGPT, DALL-E, Stable Diffusion and many models outside of healthcare domains. These models are characterized by in-context learning: the ability to perform tasks for which they were never explicitly trained.

Accordingly, going forward, foundation models for medicine provide the potential for a diverse, integration of medical data that includes electronic health records, images, lab values, biologic layers such as the genome and gut microbiome, and social determinants of health. (...)

I should point out that it’s not exactly a clear or rapid path because there is a paucity of large or even massive medical datasets, and the computing power required to run these models is expensive and not widely available. But the opportunity to get to machine-powered, advanced medical reasoning skills, that would come in handy (an understatement) with so many tasks in medical research (above Figure), and patient care, such as generating high-quality reports and notes, providing clinical decision support for doctors or patients, synthesizing all of a patient’s data from multiple sources, dealing with payors for pre-authorization, and so many routine and often burdensome tasks, is more than alluring.

by Eric Topol, Ground Truths | Read more:

Images: Sevilla J. et al, arXiv 9 March 2022

[ed. PetaFLOPS. Billions of petaFLOPS. Way back in the dark ages of 2007, the fastest computer at that time IBM's Blue Gene, apparently maxed out at a half-petaFLOP. By the way, Microsoft - not to be left out of the AI race - recently unveiled its own conversational AI tool - Bard, similar to ChatGPT (Vox). See also: Multimodal biomedical AI (Nature Medicine).]

Tuesday, February 7, 2023

Review: Samsung Galaxy A14 5G

Image: Samsung

Wired

It's $200! Good performance. Nice screen. Two-day battery life. Solid camera. Includes 64 GB of storage and a microSD card slot, plus a headphone jack and NFC for contactless payments. Runs the latest version of Android and will get two OS upgrades and four years of security updates. Works on all major US networks.

Tired

No IP rating. Mono speaker isn't great.

No IP rating. Mono speaker isn't great.

[ed. Not an endorsement - by me anyway - but if you're looking for a good cheap phone, this might be worth checking out.]

The Real Obstacle to Nuclear Power

Nuclear power is in a strange position today. Those who worry about climate change have come to see that it is essential. The warming clock is ticking—another sort of countdown—and replacing fossil fuels is much easier with nuclear power in the equation. And yet the industry, in many respects, looks unready to step into a major role. It has consistently flopped as a commercial proposition. Decade after decade, it has broken its promises to deliver new plants on budget and on time, and, despite an enviable safety record, it has failed to put to rest the public’s fear of catastrophic accidents. Many of the industry’s best minds know they need a new approach, and soon. For inspiration, some have turned toward SpaceX, Tesla, and Apple. (...)

"Why Can't You Build Us a Nuclear Plant?"

When I started reporting this article, I imagined it might be a diatribe against the environmental movement’s resistance to nuclear power. For a generation or more, the United States has been fighting climate change—and all the other ills that result from fossil fuels—with one hand tied behind its back. Bruce Babbitt, a former secretary of the interior and governor of Arizona, was on a presidential commission to evaluate nuclear power after the Three Mile Island plant’s partial meltdown in 1979, the U.S. industry’s worst accident. Though no one died or was even injured—and the accident led to new protocols and training under which the plant’s second, intact reactor operated uneventfully until 2019—the accident hardened the public and environmentalists against nuclear energy. After that, as Babbitt told me, “opposition in the environmental community was near unanimous. The position was ‘No new nuclear plants, and we should phase out the existing nuclear base.’ ” Which was the road the U.S. took. Today legacy nuclear power supplies about 20 percent of American electricity, but the country has fired up only one new power reactor since 1996.

From an environmental point of view, this seems like a perverse strategy, because nuclear power, as most people know, is carbon-free—and is also, as fewer people realize, fantastically safe. Only the 1986 accident at Chernobyl, in Ukraine, has caused mass fatalities from radioactivity, and the plant there was subpar and mismanaged, by Western standards. Excluding Chernobyl, the total number of deaths attributed to a radiation accident at a commercial nuclear-power plant is zero or one, depending on your interpretation of Japan’s 2011 Fukushima accident. The Fukushima evacuation certainly caused deaths; Japanese authorities have estimated that more than 2,000 people may have died from disruptions in services such as nursing care and from stress-related factors such as alcoholism and depression. (Some experts now believe that the evacuation was far too large.) Even so, Japan’s decision to shut down its nuclear plants has been estimated to cause multiples of that death toll, on account of the increased fossil-fuel pollution that followed.

The real challenge with giant nuclear plants like Fukushima and Three Mile Island is not making them safe but doing so at a reasonable price, which is the problem that companies like Kairos are trying to solve. But even people who feel scared of nuclear power do not dispute that fossil fuels are orders of magnitude more dangerous. One study, published in 2021, estimated that air pollution from fossil fuels killed about 1 million people in 2017 alone. In fact, nuclear power’s safety record to date is easily on par with the wind and solar industries, because wind turbines and rooftop panels create minor risks such as falls and fire. As for nuclear waste, it has turned out to be a surprisingly manageable problem, partly because there isn’t much of it; all of the spent fuel the U.S. nuclear industry has ever created could be buried under a single football field to a depth of less than 10 yards, according to the Department of Energy. Unlike coal waste, which is of course spewed into the air we breathe, radioactive waste is stored in carefully monitored casks.

And so environmentalists, I thought, were betraying the environment by stigmatizing nuclear power. But I had to revise my view. Even without green opposition, nuclear power as we knew it would have fizzled—today’s environmentalists are not the main obstacle to its wide adoption. (...)

Because solar and wind power are inherently intermittent, they require other energy sources to even out peaks and dips. Natural gas and coal can do that, but of course the goal is to retire them. Batteries can help but are much too expensive to rely on at present, and mining, manufacturing, and disposing of them entail their own environmental harms. Also, nuclear power is the only efficient way to provide zero-carbon heat for high-temperature industrial processes such as steelmaking, which account for about a fifth of energy consumption.

Perhaps most important, adding solar and wind capacity becomes more expensive and controversial as the most accessible land is used up. Nuclear energy’s footprint is extremely small. (...)

Finally, as low- and middle-income countries develop over the next several decades, they will almost double the world’s demand for electricity. Total global energy consumption will rise by 30 percent by 2050, according to the International Energy Agency. Meeting this challenge while reducing carbon emissions will be much harder, if not impossible, without a nuclear assist.

Recognizing as much, three consecutive administrations—Barack Obama’s, Donald Trump’s, and now Joe Biden’s—have included next-generation nuclear power in their policy agenda. Both parties in Congress support federal R&D funding, which has run into the billions in the past few years. Two-thirds of the states have told the Associated Press they want to include nuclear power in their green-energy plans. “Today the topic of new nuclear is front of mind for all our member utilities,” says Doug True, a senior vice president and the chief nuclear officer of the Nuclear Energy Institute, an industry trade group. “We have states saying, ‘Why can’t you build us a nuclear plant?’ ”

Thanks to those developments, the table is set for nuclear power in a way that has not been true for two generations. So what is the main problem for the nuclear-power industry? In sum: the nuclear-power industry.

by Jonathan Rauch, The Atlantic | Read more:

Image: Brian Finke for The Atlantic

"Why Can't You Build Us a Nuclear Plant?"

When I started reporting this article, I imagined it might be a diatribe against the environmental movement’s resistance to nuclear power. For a generation or more, the United States has been fighting climate change—and all the other ills that result from fossil fuels—with one hand tied behind its back. Bruce Babbitt, a former secretary of the interior and governor of Arizona, was on a presidential commission to evaluate nuclear power after the Three Mile Island plant’s partial meltdown in 1979, the U.S. industry’s worst accident. Though no one died or was even injured—and the accident led to new protocols and training under which the plant’s second, intact reactor operated uneventfully until 2019—the accident hardened the public and environmentalists against nuclear energy. After that, as Babbitt told me, “opposition in the environmental community was near unanimous. The position was ‘No new nuclear plants, and we should phase out the existing nuclear base.’ ” Which was the road the U.S. took. Today legacy nuclear power supplies about 20 percent of American electricity, but the country has fired up only one new power reactor since 1996.

From an environmental point of view, this seems like a perverse strategy, because nuclear power, as most people know, is carbon-free—and is also, as fewer people realize, fantastically safe. Only the 1986 accident at Chernobyl, in Ukraine, has caused mass fatalities from radioactivity, and the plant there was subpar and mismanaged, by Western standards. Excluding Chernobyl, the total number of deaths attributed to a radiation accident at a commercial nuclear-power plant is zero or one, depending on your interpretation of Japan’s 2011 Fukushima accident. The Fukushima evacuation certainly caused deaths; Japanese authorities have estimated that more than 2,000 people may have died from disruptions in services such as nursing care and from stress-related factors such as alcoholism and depression. (Some experts now believe that the evacuation was far too large.) Even so, Japan’s decision to shut down its nuclear plants has been estimated to cause multiples of that death toll, on account of the increased fossil-fuel pollution that followed.

The real challenge with giant nuclear plants like Fukushima and Three Mile Island is not making them safe but doing so at a reasonable price, which is the problem that companies like Kairos are trying to solve. But even people who feel scared of nuclear power do not dispute that fossil fuels are orders of magnitude more dangerous. One study, published in 2021, estimated that air pollution from fossil fuels killed about 1 million people in 2017 alone. In fact, nuclear power’s safety record to date is easily on par with the wind and solar industries, because wind turbines and rooftop panels create minor risks such as falls and fire. As for nuclear waste, it has turned out to be a surprisingly manageable problem, partly because there isn’t much of it; all of the spent fuel the U.S. nuclear industry has ever created could be buried under a single football field to a depth of less than 10 yards, according to the Department of Energy. Unlike coal waste, which is of course spewed into the air we breathe, radioactive waste is stored in carefully monitored casks.

And so environmentalists, I thought, were betraying the environment by stigmatizing nuclear power. But I had to revise my view. Even without green opposition, nuclear power as we knew it would have fizzled—today’s environmentalists are not the main obstacle to its wide adoption. (...)

Because solar and wind power are inherently intermittent, they require other energy sources to even out peaks and dips. Natural gas and coal can do that, but of course the goal is to retire them. Batteries can help but are much too expensive to rely on at present, and mining, manufacturing, and disposing of them entail their own environmental harms. Also, nuclear power is the only efficient way to provide zero-carbon heat for high-temperature industrial processes such as steelmaking, which account for about a fifth of energy consumption.

Perhaps most important, adding solar and wind capacity becomes more expensive and controversial as the most accessible land is used up. Nuclear energy’s footprint is extremely small. (...)

Finally, as low- and middle-income countries develop over the next several decades, they will almost double the world’s demand for electricity. Total global energy consumption will rise by 30 percent by 2050, according to the International Energy Agency. Meeting this challenge while reducing carbon emissions will be much harder, if not impossible, without a nuclear assist.

Recognizing as much, three consecutive administrations—Barack Obama’s, Donald Trump’s, and now Joe Biden’s—have included next-generation nuclear power in their policy agenda. Both parties in Congress support federal R&D funding, which has run into the billions in the past few years. Two-thirds of the states have told the Associated Press they want to include nuclear power in their green-energy plans. “Today the topic of new nuclear is front of mind for all our member utilities,” says Doug True, a senior vice president and the chief nuclear officer of the Nuclear Energy Institute, an industry trade group. “We have states saying, ‘Why can’t you build us a nuclear plant?’ ”

Thanks to those developments, the table is set for nuclear power in a way that has not been true for two generations. So what is the main problem for the nuclear-power industry? In sum: the nuclear-power industry.

by Jonathan Rauch, The Atlantic | Read more:

Image: Brian Finke for The Atlantic

Labels:

Business,

Design,

Environment,

Government,

Politics,

Science,

Technology

Monday, February 6, 2023

Biden Is Reviving Democratic Capitalism

How can inflation be dropping at the same time job creation is soaring?

It has taken one of the oldest presidents in American history, who has been in politics for over half a century, to return the nation to an economic paradigm that dominated public life between 1933 and 1980, and is far superior to the one that has dominated it since.

Call it democratic capitalism.

The Great Crash of 1929 followed by the Great Depression taught the nation a crucial lesson that we forgot after Ronald Reagan’s presidency: the so-called “free market” does not exist. Markets are always and inevitably human creations. They reflect decisions by judges, legislators and government agencies as to how the market should be organized and enforced – and for whom.

The economy that collapsed in 1929 was the consequence of decisions that organized the market for a monied elite, allowing nearly unlimited borrowing, encouraging people to gamble on Wall Street, suppressing labor unions, holding down wages, and permitting the Street to take huge risks with other people’s money.

Franklin D Roosevelt and his administration reversed this. They reorganized the market to serve public purposes – stopping excessive borrowing and Wall Street gambling, encouraging labor unions, establishing social security and creating unemployment insurance, disability insurance and a 40-hour workweek. They used government spending to create more jobs. During the second world war, they controlled prices and put almost every American to work.

Democratic and Republican administrations enlarged and extended democratic capitalism. Wall Street was regulated, as were television networks, airlines, railroads and other common carriers. CEO pay was modest. Taxes on the highest earners financed public investments in infrastructure (such as the national highway system) and higher education.

America’s postwar industrial policy spurred innovation. The Department of Defense developed satellite communications, container ships and the internet. The National Institutes of Health did trailblazing basic research in biochemistry, DNA and infectious diseases.

Public spending rose during economic downturns to encourage hiring. Even Richard Nixon admitted “we’re all Keynesians”. Antitrust enforcers broke up AT&T and other monopolies. Small businesses were protected from giant chain stores. By the 1960s, a third of all private-sector workers were unionized.

Large corporations sought to be responsive to all their stakeholders – not just shareholders but employees, consumers, the communities where they produced goods and services, and the nation as a whole.

Then came a giant U-turn. The Opec oil embargo of the 1970s brought double-digit inflation followed by the Fed chair Paul Volcker’s effort to “break the back” of inflation by raising interest rates so high the economy fell into deep recession.

All of which prepared the ground for Reagan’s war on democratic capitalism.

From 1981, a new bipartisan orthodoxy emerged that the so-called “free market” functioned well only if the government got out of the way (conveniently forgetting that the market required government). The goal of economic policy thereby shifted from public welfare to economic growth. And the means shifted from public oversight of the market to deregulation, free trade, privatization, “trickle-down” tax cuts, and deficit-reduction – all of which helped the monied interests make more money.

What happened next? For 40 years, the economy grew but median wages stagnated. Inequalities of income and wealth ballooned. Wall Street reverted to the betting parlor it had been in the 1920s. Finance once again ruled the economy. Spurred by hostile takeovers, corporations began focusing solely on maximizing shareholder returns – which led them to fight unions, suppress wages, abandon their communities and outsource abroad.

Corporations and the super-rich used their increasing wealth to corrupt politics with campaign donations – buying tax cuts, tax loopholes, government subsidies, bailouts, loan guarantees, non-bid government contracts and government forbearance from antitrust enforcement, allowing them to monopolize markets.

Democratic capitalism, organized to serve public purposes, all but disappeared. It was replaced by corporate capitalism, organized to serve the monied interests.

Joe Biden is reviving democratic capitalism.

From the Obama administration’s mistake of spending too little to pull the economy out of the Great Recession, he learned that the pandemic required substantially greater spending, which would also give working families a cushion against adversity. So he pushed for the giant $1.9tn American Rescue Plan.

This was followed by a $550bn initiative to rebuild bridges, roads, public transit, broadband, water and energy systems. And in 2022, the biggest investment in clean energy in American history – expanding wind and solar power, electric vehicles, carbon capture and sequestration, and hydrogen and small nuclear reactors. This was followed by the largest public investment ever in semiconductors, the building blocks of the next economy. (...)

I don’t want to overstate Biden’s accomplishments. His ambitions for childcare, eldercare, paid family and medical leave were thwarted by Senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema. And now he has to contend with a Republican House.

Biden’s larger achievement has been to change the economic paradigm that has reigned since Reagan. He is teaching America a lesson we once knew but have forgotten: that the “free market” does not exist. It is designed. It either advances public purposes or it serves the monied interests.

[ed. Nice concise history lesson.]

It has taken one of the oldest presidents in American history, who has been in politics for over half a century, to return the nation to an economic paradigm that dominated public life between 1933 and 1980, and is far superior to the one that has dominated it since.

Call it democratic capitalism.

The Great Crash of 1929 followed by the Great Depression taught the nation a crucial lesson that we forgot after Ronald Reagan’s presidency: the so-called “free market” does not exist. Markets are always and inevitably human creations. They reflect decisions by judges, legislators and government agencies as to how the market should be organized and enforced – and for whom.

The economy that collapsed in 1929 was the consequence of decisions that organized the market for a monied elite, allowing nearly unlimited borrowing, encouraging people to gamble on Wall Street, suppressing labor unions, holding down wages, and permitting the Street to take huge risks with other people’s money.

Franklin D Roosevelt and his administration reversed this. They reorganized the market to serve public purposes – stopping excessive borrowing and Wall Street gambling, encouraging labor unions, establishing social security and creating unemployment insurance, disability insurance and a 40-hour workweek. They used government spending to create more jobs. During the second world war, they controlled prices and put almost every American to work.

Democratic and Republican administrations enlarged and extended democratic capitalism. Wall Street was regulated, as were television networks, airlines, railroads and other common carriers. CEO pay was modest. Taxes on the highest earners financed public investments in infrastructure (such as the national highway system) and higher education.

America’s postwar industrial policy spurred innovation. The Department of Defense developed satellite communications, container ships and the internet. The National Institutes of Health did trailblazing basic research in biochemistry, DNA and infectious diseases.