[ed. Fell down the Rabbit Hole this morning reading about de-aging technology (specifically, the new Indiana Jones movie). General consensus seems to be: it works pretty well sometimes but not others (eg. IJ) and has a ways to go before becoming something really seamless and unnoticeable (see also: here). I love these scenes from Martin Scorsese's "The Irishman". First because it's a great movie, second because the acting is wonderful (in Al Pacino's case as union boss Jimmy Hoffa some have said overacting, but I disagree strongly - see for yourself), and third because the anti-aging technology used here is about as good as it gets. Btw, for an example of early anti-aging efforts, see: The Curious Case of Benjamin Button where Brad Pitt's face is simply pasted over those of some babies and children as he grew older/younger. Weird but still a great movie!]

Saturday, August 5, 2023

Friday, August 4, 2023

Autoenshittification

Your car is stuffed full of microchips, a fact the world came to appreciate after the pandemic struck and auto production ground to a halt due to chip shortages. Of course, that wasn't the whole story: when the pandemic started, the automakers panicked and canceled their chip orders, only to immediately regret that decision and place new orders.

But it was too late: semiconductor production had taken a serious body-blow, and when Big Car placed its new chip orders, it went to the back of a long, slow-moving line. It was a catastrophic bungle: microchips are so integral to car production that a car is basically a computer network on wheels that you stick your fragile human body into and pray.

The car manufacturers got so desperate for chips that they started buying up washing machines for the microchips in them, extracting the chips and discarding the washing machines like some absurdo-dystopian cyberpunk walnut-shelling machine:

https://www.autoevolution.com/news/desperate-times-companies-buy-washing-machines-just-to-rip-out-the-chips-187033.html

These digital systems are a huge problem for the car companies. They are the underlying cause of a precipitous decline in car quality. From touch-based digital door-locks to networked sensors and cameras, every digital system in your car is a source of endless repair nightmares, costly recalls and cybersecurity vulnerabilities:

https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/quality-new-vehicles-us-declining-more-tech-use-study-shows-2023-06-22/

What's more, drivers hate all the digital bullshit, from the janky touchscreens to the shitty, wildly insecure apps. Digital systems are drivers' most significant point of dissatisfaction with the automakers' products:

https://www.theverge.com/23801545/car-infotainment-customer-satisifaction-survey-jd-power (...)

But even amid all the complaining about cars getting stuck in the Internet of Shit, there's still not much discussion of why the car-makers are making their products less attractive, less reliable, less safe, and less resilient by stuffing them full of microchips. Are car execs just the latest generation of rubes who've been suckered by Silicon Valley bullshit and convinced that apps are a magic path to profitability?

Nope. Car execs are sophisticated businesspeople, and they're surfing capitalism's latest – and last – hot trend: dismantling capitalism itself.

Now, leftists have been predicting the death of capitalism since The Communist Manifesto, but even Marx and Engels warned us not to get too frisky: capitalism, they wrote, is endlessly creative, constantly reinventing itself, re-emerging from each crisis in a new form that is perfectly adapted to the post-crisis reality:

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/31/books/review/a-spectre-haunting-china-mieville.html

But capitalism has finally run out of gas. In his forthcoming book, Techno Feudalism: What Killed Capitalism, Yanis Varoufakis proposes that capitalism has died – but it wasn't replaced by socialism. Rather, capitalism has given way to feudalism:

https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/451795/technofeudalism-by-varoufakis-yanis/9781847927279

Under capitalism, capital is the prime mover. The people who own and mobilize capital – the capitalists – organize the economy and take the lion's share of its returns. But it wasn't always this way: for hundreds of years, European civilization was dominated by rents, not markets.

A "rent" is income that you get from owning something that other people need to produce value. Think of renting out a house you own: not only do you get paid when someone pays you to live there, you also get the benefit of rising property values, which are the result of the work that all the other homeowners, business owners, and residents do to make the neighborhood more valuable.

The first capitalists hated rent. They wanted to replace the "passive income" that landowners got from taxing their serfs' harvest with active income from enclosing those lands and grazing sheep in order to get wool to feed to the new textile mills. They wanted active income – and lots of it.

Capitalist philosophers railed against rent. The "free market" of Adam Smith wasn't a market that was free from regulation – it was a market free from rents. The reason Smith railed against monopolists is because he (correctly) understood that once a monopoly emerged, it would become a chokepoint through which a rentier could cream off the profits he considered the capitalist's due:

https://locusmag.com/2021/03/cory-doctorow-free-markets/

Today, we live in a rentier's paradise. People don't aspire to create value – they aspire to capture it. In Survival of the Richest, Doug Rushkoff calls this "going meta": don't provide a service, just figure out a way to interpose yourself between the provider and the customer:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/09/13/collapse-porn/#collapse-porn

Don't drive a cab, create Uber and extract value from every driver and rider. Better still: don't found Uber, invest in Uber options and extract value from the people who invest in Uber. Even better, invest in derivatives of Uber options and extract value from people extracting value from people investing in Uber, who extract value from drivers and riders. Go meta.

Stardom is Not a Worthy Pursuit’: Julia Louis-Dreyfus

At the first table read, Holofcener remembers her horseplay with the actor who played Seinfeld’s infamous Elaine Benes all but overshadowing the co-lead, James Gandolfini: “We could finish each other’s sentences – she so got the materials, she so got me. She would jump in with ideas that were generally fantastic. And we would laugh until we peed. Jim would look at us like: ‘Boy, am I in a chick flick or what?’” (...)

It is classic Holofcener: petty, narcissistic and pitiable, yet hilarious and relatable. Louis-Dreyfus knew she could trust Holofcener because of that unique perspective: “There’s an honesty and authenticity in her writing that makes me comfortable with her point of view.” (...)

Fair enough: from the outside, it’s difficult to identify any missteps across her 40-year career. Having played the self-serving vice-president Selina Meyer in Veep from 2012 to 2019, Louis-Dreyfus is as beloved today as she was in the early 90s, when she incarnated Seinfeld’s self-serving, big-haired shover. She is the most garlanded Primetime Emmy and Screen Actors Guild award-winner in history; in 2018, she received the Mark Twain prize for American Humor.

Louis-Dreyfus’s appeal, agree Holofcener and Armando Iannucci, the creator of Veep, is her hunger to stray beyond the pale. With the hapless Selina, says Iannucci, “she was always the first pushing it further in terms of her having no principles. She’s put in charge of a healthy eating project, one of the pathetic things presidents give their vice-presidents to keep them busy. And Julia was quite keen to push the fact that Selina cannot abide anyone who’s overweight, in a slightly uneasy way. She’s quite happy for the audience to be appalled by her character.”

At the same time, says Iannucci, “there’s a genuineness there as well. You can see why those characters might have arrived at that point psychologically.”

If Louis-Dreyfus did have anything close to a misstep, it was her dispiriting spell at Saturday Night Live, from 1982 to 1985. She had a hard time as the youngest female cast member in what she has characterised as a druggy boys’ club. (She did, though, forge a bond with an equally miserable Larry David, who would later co-create Seinfeld.) But even that cultivated a guiding presence of mind: when she got the boot, she resolved that she would only keep acting if it was fun.

Most young actors would cut off a limb to make it. Why not Louis-Dreyfus? “Maybe because I was so fundamentally unhappy for those three years,” she says. She knew it didn’t have to be like this from her time in the Chicago improv troupes the Second City and the Practical Theatre Company. “I really enjoyed doing work with my friends that was thrilling and collaborative and ensemble-y. And so I knew from having fun, right?”

SNL wasn’t “the most wretched experience of my life”, she concedes. “But it was very challenging. I knew I couldn’t keep that going. And if this was what it meant to be in showbusiness, I wanted nothing to do with it. I had this feeling: if I can’t find the fun again, I can walk away from this.”

Fun and practicality seem to be the cornerstones of Louis-Dreyfus’s attitude. In 1989, David and Jerry Seinfeld signed her up to play Elaine. A recent New York Times article marking 25 years since the Seinfeld finale posited that it still resonates because the characters “flouted societal conventions and the rules of traditional adulthood”, constructs increasingly inaccessible to younger viewers. Louis-Dreyfus isn’t sure. “I don’t know if I’m smart enough to draw a conclusion like that,” she says. “At the end of the day, it was just fucking funny, and that holds up.”

In 2017, while shooting Veep, Louis-Dreyfus was diagnosed with breast cancer, suspending filming for a year. She was treated and underwent a double reconstruction (and has campaigned for all women get the same opportunity, regardless of financial ability). The producer of You Hurt My Feelings recently remarked on her and Holofcener’s wonder at human narcissism. That hasn’t changed since her brush with mortality, she says: “The bullshit is always there and I love exploring it. I’m very interested in the warts and all of human beings and their interactions with each other.” (...)

In Wiser Than Me, Louis-Dreyfus interviews older women, from Amy Tan to Jane Fonda, about their life experiences. Fonda’s documentary Jane Fonda in Five Acts inspired the idea. “I was completely stunned by the scope of her life, and that I didn’t really fully understand everything that she had done, accomplished, experienced,” she says. “It led me to the next thought: what about all the other older women out there who have had a lot of life? I want to hear from them, too. There’s enormous value in speaking to women who have been there, done that and can give you the sage advice.”

Fonda told her that she regretted getting cosmetic surgery. Last year, Holofcener told this paper that virtually every female actor over 50 had “distorted their own face” with surgery. Louis-Dreyfus’s stance is that people should do what they want: “I’m not making any judgment whatsoever of anyone who does it. Having said that, I have not had any plastic surgery. It’s not something I’m keen on doing – as, you know, demonstrated by my face in the movie.” (...)

Thursday, August 3, 2023

The Great Rolex Recession is Here

X Will Never Be the “Everything App” But Uber Might

My personal opinion (not prediction, opinion) is that this is a stock that could trade to $100 per share over the next two to three years. And the reason why I think this is possible is not a stretch to imagine today. While Elon Musk fantasizes about the possibility of Twitter users turning over their financial information to his demented fighting pit circus, Uber has already laid the groundwork to actually become the “Everything App” that “X” will never be. Uber has a ten year head start technologically, a massive user base (that is actually paying money) and a revenue base across which to spread the cost of this vision.

Uber is a verb. It’s how people get places. Not just on short notice like the original black town car-hailing service it started out as. You can book a car days or hours in advance now. You can be picked up by a professional driver in a Cadillac Escalade or an amateur driver in a Kia Sorento, depending on how much you want to spend. This business was crippled during the pandemic, which is why the stock fell into the 20’s. It’s come back with a vengeance. Every kind of user – business travelers, work commuters, vacationers, drinkers, partiers, urbanites without cars, teens, the elderly, you name it, they’re riding again.

Additionally, Uber has become a verb describing not just how people get places but also how they get things. The Uber Eats business now has more regular users than the Uber Rides business. Before the pandemic, Eats looked like a loser and many in the investment community were exhorting the company to wind it down or sell it off. When the plague came, Eats literally saved this company’s life. It’s now in a hyper-scaling phase with new users and drivers flocking to the platform as other, less reliable services fade away. This business has not slowed down during the reopening, like so many lockdown businesses have (Zoom, Docusign, Peloton, Zillow). If anything, it has accelerated.

Finally, Uber has been adding even more services now that its logistics and payments have been built out and proven. They’re delivering groceries. They’re bringing people items from the convenience store. Their Drizzly app delivers wine, beer and liquor all day and night. They’re bringing customers prescriptions from the pharmacy. They launched a freight business to help companies ship items by truck.

If any company today has the chance of becoming the “everything app”, it’s this one. Unlike legacy Twitter (I refuse to call it X), which barely knows anything about its users (hence the failure to build a profitable advertising business), Uber knows quite a bit about the people who use its app. For starters, they use it to pay for things. They’re using it in their own name with a credit card on file, not anonymously or pseudonymously. Most importantly, people don’t open the Uber app to argue over abortion rights or Ukraine or to casually join outrage mobs and accuse random strangers of racism. They open it because they have better things to do. They want to go somewhere or get something. Twitter is for people who have nothing to do, so they scroll it looking for a laugh or a fight.

I should point out that almost no one uses Twitter. It’s got an outsized voice in our culture because journalists and people in the media are obsessed with it and constantly talking about it. Twitter is the stock market for reporters – it’s how they can see what takes are rising and falling in popularity and what (or whom) they should be covering. In the real world, only the weirdest people you know (maybe yourself included) are on it. Only 23% of US adults use Twitter (Facebook is 69%, YouTube is 81%). In a survey this past spring, 60% of people who had used Twitter told Pew they were taking a break from it. Some 25% of current users said they were unlikely to still be using it in a year. With the name change and unintentional (intentional?) destruction of the product, 25% might be low. The odds of this platform evolving to provide financial services, rides, deliveries, video chat, gaming, etc like the super-apps in China do is very low.

Uber had a formidable competitor in Lyft in the United States but they’ve basically beaten it into submission. They need Lyft to stay alive so that they can’t be seen as a monopolist but, in practice, that’s what they are becoming on the Rides side. Lyft needs an activist to step in. It’s not big enough to compete with Uber and might make more sense as a part of someone else’s larger business. If anyone wants it. The CEO of Uber, Dara Khosrowshahi, who had taken over when the founder, Travis Kalanick, was pushed out a decade ago, rightfully saw that a robust driver ecosystem was the key to winning the category. Offering a more generous take-rate for the drivers meant a fully-stocked supply side so that users would always have cars ready to get them. This became habit-forming as people began to check Uber first. It was expensive but it paid off. Dara won the user experience game by simultaneously winning the drivers game. They’ll be writing about this in business school textbooks someday. (...)

Now, I want you to keep in mind that this is a global business and it is a large one, despite the fact that Uber is not yet mentioned in the same breath as the Googles, the Apples and the Amazons. It’s not yet as profitable as the Magnificent Seven companies and it is a much younger company (founded in 2008, public since the spring of 2019). But it is huge and growing fast.

Wednesday, August 2, 2023

Bajau: Last of the Sea Nomads

Diana Botutihe was born at sea. Now in her 50s, she has spent her entire life on boats that are typically just 5m long and 1.5m wide. She visits land only to trade fish for staples such as rice and water, and her boat is filled with the accoutrements of everyday living – jerry cans, blackened stockpots, plastic utensils, a kerosene lamp and a pair of pot plants.

Diana is one of the world's last marine nomads; a member of the Bajau ethnic group, a Malay people who have lived at sea for centuries, plying a tract of ocean between the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia. The origins of the Bajau diaspora are recounted in the legend of a princess from Johor, Malaysia, who was washed away in a flash flood. Her grief-stricken father ordered his subjects to depart, returning only when they'd found his daughter.

Over generations, the Bajau adapted to their maritime environment and, though marginalised, their knowledge was revered by the great Malay sultans, who counted on them to establish and protect trade routes. They are highly skilled free divers, plunging to depths of 30m and more to hunt pelagic fish or search for pearls and sea cucumbers – a delicacy among the Bajau and a commodity they have traded for centuries.

Since diving is an everyday activity, the Bajau deliberately rupture their eardrums at an early age. "You bleed from your ears and nose, and you have to spend a week lying down because of the dizziness," says Imran Lahassan, of the community of Torosiaje in North Sulawesi, Indonesia. "After that you can dive without pain." Unsurprisingly, most older Bajau are hard of hearing. When diving, they wear hand-carved wooden goggles with glass lenses, hunting with spear guns fashioned from boat timber, tyre rubber and scrap metal.

[ed. More pictures here. See also: Freediving: is this a sport – or ‘French existentialist swimming’? (On the new Netflix documentary The Deepest Breath).]

Tuesday, August 1, 2023

My Beautiful Friend

I could not have discovered I was plain without discovering K was pretty. She is my friend of many years. Back then, it obsesses me: how we make each other exist. We attend elementary school together, then high school. She enrolls at a nearby college. Her tall grants me my short; my plump her skinny; her leonine features my pedestrian ones. I resent her as much as I exult in her company. In between us, and without words for it, the female universe dilates, a continuum whose comparative alchemy seems designed to confront me, make me suffer, lift her up. Her protagonism diminishes me, or does it? I confuse myself for a long time thinking I am the planet, and K is the sun. It takes me a long time to forgive her.

Comparison steals my joy, but it also gives me a narrative. All in all, it feels radical to make a world together, she and I, a silent tournament of first kisses, compliments, report cards. I live at a fixed point from K, her lucky arms, her lucky neck, her lucky elbows. I pursue beautiful friends like some women do men who will strike them in bed at night. On account of our addictive relativity. On account of my envy, which I’ve made, like many women, the secret passion of my life.

There’s something gorgeously petty about many women’s lives. They’re not trying to be great. They’re trying to be better. It’s why women diet together; dye their hair light, then dark, then light again; dress for each other; race to get engaged; wait to get divorced; find a taken man more attractive than a free one. Become girlbosses in droves and then give it up. A woman can spend her whole life in real or imagined competition with her friends, finding herself in the gaps between them. Especially in the game of looks, there is no excellence that is not another woman’s inadequacy, no abundance that does not mean lack. A great beauty is discovered, like crude oil, or gold. That means in a parched desert, or a dirty riverbed, where the rest of us must languish. Our democratic sensibility commands us to raze all unfairness. Yet the way we sacralize beauty, our treatment of the women who try to level it, our satisfaction when no one can, calls our bluff.

For me, the humiliations stack up. I nurse them like little children. I pick at them like scabs. The horrid boy I desperately love, who pretends to love me, studying K’s legs on the trampoline. We are seventeen, and I study them too. Up and down, slender, hairless, vanishing up the thighs, into the sun. Later he sends her a message on Facebook. She does nothing to betray me. What I want is for those legs and the mat of the trampoline to go rigid, to snap, for her bones to spray and splinter, to pierce me through the eyes, so I cannot look at either of us anymore.

Or, a couple years later, when I believe I’ve matured, gotten over it, displaying my fake ID at a college party. It’s my friend’s, I explain. It’s K’s. How funny. It works, we look just enough alike. A drunken classmate laughs. “Yes,” he says. “Except she’s hotter than you.” My face silences him, then the room. His words spread my legs, pass a hand through me, find something dying. He apologizes until I console him. I return to my dorm and drown in abjection, almost pleasurably at this point. I’d like to call my mother, whom I resemble. Except that in all of our talks of puberty, she omitted this. She gave me my face and felt guilty; I had to learn for myself how my suffering held something up.

My own inglorious adolescence ends with me dumped, over brunch, at twenty. He has a strong jaw which dazes and a soft birthmark, near the mouth. He is ten years older than me. That last bit is not the part that hurts. It’s that he’s telling me about another girl. “She’s amazing,” he says. “I haven’t felt like this in a long time.” I think of what we’ve done for a long time and I go to the bathroom and vomit. When I come back he’s still speaking. I wonder, in silence, what it would be like to be the sort of girl about whom they say, he can’t shut up about her. “She’s a writer,” he tells me, with love in his eyes. He looks so handsome, I want to kiss him, exactly now, when, because, he can’t shut up about her. I go home, look her up, write a poem, get over him as soon as I get it published, thinking vaguely, see, there, that was easy, take that—I might be less lovely, but there are other competitions, I can be a writer too. (...)

From Austen to Ferrante, women’s literature is ripe with dyads of women, made up of a beautiful half and a less beautiful half. Here, the arbitrariness of beauty plays out in long, anguished plots, games of chutes and ladders, whereby some women find themselves socially, magically, economically mobile, and others do not, at least not so easily. We recognize the “winner” as soon as we read what she looks like. In first-person stories, more often than not, it’s not the narrator. These plain heroines yearn for, resent, are fascinated by, love, hate, cannot stay away from, their more beautiful, fortunate counterparts. They articulate a precisely feminine pain I know well, worse than menstrual cramps. A sense of one’s own plainness. Inferiority. An envy so profound and wistful it is almost sexually charged.

by Grazie Sophia Christie, The Point | Read more:

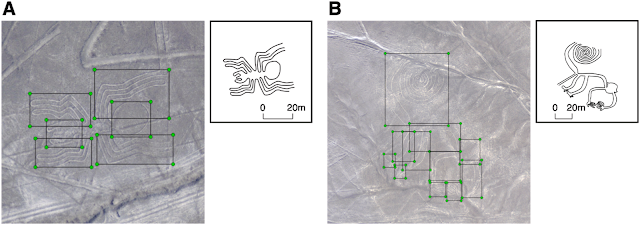

Accelerating the Discovery of New Nasca Geoglyphs Using Deep Learning

AI in nature is always interesting, but nature AI as applied to archaeology is even more so. Research led by Yamagata University aimed to identify new Nasca lines — the enormous “geoglyphs” in Peru. You might think that, being visible from orbit, they’d be pretty obvious — but erosion and tree cover from the millennia since these mysterious formations were created mean there are an unknown number hiding just out of sight. After being trained on aerial imagery of known and obscured geoglyphs, a deep learning model was set free on other views, and amazingly it detected at least four new ones, as you can see below [ed, above]. Pretty exciting! via: (TC)

[ed. See also (original paper): Accelerating the discovery of new Nasca geoglyphs using deep learning (ScienceDirect).]

Monday, July 31, 2023

The Secret History of Gun Rights: How Lawmakers Armed the N.R.A.

[ed. My admiration for Representative John Dingell (Michigan) just suffered a severe hit. You can be right about a lot of things but blind to others. See his Wikipedia entry for a full accounting of his many accomplishments:]

"During his time in Congress in addition to protecting the automobile industry important to his district, Dingell was instrumental in passage of the Medicare Act, the Water Quality Act of 1965, Clean Water Act of 1972, the Endangered Species Act of 1973, the Clean Air Act of 1990, and the Affordable Care Act, among others. He was most proud of his work on the Civil Rights Act of 1964." (Wikipedia)

The Lunar Codex

A Time Capsule of Human Creativity, Stored in the Sky (NYT)

The Lunar Codex, an archive of contemporary art, poetry and other cultural artifacts of life on Earth, is headed to the moon.

Later this year, the Lunar Codex — a vast multimedia archive telling a story of the world’s people through creative arts — will start heading for permanent installation on the moon aboard a series of unmanned rockets.

The Lunar Codex is a digitized (or miniaturized) collection of contemporary art, poetry, magazines, music, film, podcasts and books by 30,000 artists, writers, musicians and filmmakers in 157 countries. It’s the brainchild of Samuel Peralta, a semiretired physicist and author in Canada with a love of the arts and sciences. (...)

“This is the largest, most global project to launch cultural works into space,” Peralta said in an interview. “There isn’t anything like this anywhere.” (...)

It’s divided into four time capsules, with its material copied onto digital memory cards or inscribed into nickel-based NanoFiche, a lightweight analog storage media that can hold 150,000 laser-etched microscopic pages of text or photos on one 8.5-by-11-inch sheet. The concept is “like the Golden Record,” Peralta said, referring to NASA’s own cultural time capsule of audio and images stored on a metal disc and sent into space aboard the Voyager probes in 1977. “Gold would be incredibly heavy. Nickel wafers are much, much lighter.”

by J. D. Biersdorfer, NY Times | Read more:

Image: “New Moon,” a 1980 color serigraph by the Canadian artist Alex Colville

Breaking Bad AI

GPT-4 held the previous crown in terms of context window, weighing in at 32,000 tokens on the high end. Generally speaking, models with small context windows tend to “forget” the content of even very recent conversations, leading them to veer off topic." (...)

“The challenge is making models that both never hallucinate but are still useful — you can get into a tough situation where the model figures a good way to never lie is to never say anything at all, so there’s a tradeoff there that we’re working on,” the Anthropic spokesperson said. “We’ve also made progress on reducing hallucinations, but there is more to do.” (...)

No doubt, Anthropic is feeling some sort of pressure from investors to recoup the hundreds of millions of dollars that’ve been put toward its AI tech. (...)

Most recently, Google pledged $300 million in Anthropic for a 10% stake in the startup. Under the terms of the deal, which was first reported by the Financial Times, Anthropic agreed to make Google Cloud its “preferred cloud provider” with the companies “co-develop[ing] AI computing systems.”

Sunday, July 30, 2023

All About Decaffeinated Coffee (And Tea)

How is coffee decaffeinated?

Like regular coffee, decaf coffee begins as green, unroasted beans. The hard beans are warmed and soaked in liquid to dissolve and remove the caffeine in one of four ways: using water alone, using a mixture of water and solvents (most commonly methylene chloride or ethyl acetate) applied either directly or indirectly, or using water and “supercritical carbon dioxide.”

All four methods are safe, and once the caffeine is removed (well, at least 97% of it), the beans are washed, steamed, and roasted at temperatures that evaporate all the liquids used in decaffeination.

How much caffeine is in decaf coffee?

Decaffeination removes about 97% or more of the caffeine in coffee beans. A typical cup of decaf coffee has about 2 mg of caffeine, compared to a typical cup of regular coffee, which has about 95 mg of caffeine.

Is decaf coffee bad for you?

Like all coffee, decaffeinated coffee is safe for consumption and can be part of a healthy diet.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has set a rigorous standard to ensure that any minute traces of solvents used to decaffeinate coffee are safe. FDA measures these traces in “parts per million.” After decaffeination, coffee can contain no more than 10 parts per million of, for example, methylene chloride -- that’s one one-thousandth of a percent. (...)

How much caffeine is too much?

Regulators and health authorities in the United States and around the world have concluded moderate caffeine intake can be part of healthy diets for most adults -- generally up to 400mg per day, or about 4-5 cups of coffee. Guidelines may vary for people with certain medical conditions.

[ed. See also: How Is Coffee Decaffeinated? (Britannica). And, since my late night tea prompted this inquiry: How Is Tea Decaffeinated? (Premium Teas). From the history link above: (Live Science):]

"The first commercially successful decaffeination method was invented around 1905, by German coffee merchant Ludwig Roselius. According to Atlas Obscura, one bit of lore about the origins of decaf claims that Roselius received a shipment of coffee beans that was soaked in seawater. Instead of tossing the beans, Roselius decided to process and test them. He found that the coffee had been stripped of its caffeine content but still basically tasted like coffee, albeit a bit salty.

Roselius then figured out he could use benzene — a chemical that, at the time, was also used in paint strippers and aftershave — as a solvent to remove caffeine from coffee beans. His company, Kaffee HAG, was the first to produce instant decaf coffee. The coffee was sold as "Sanka" in the United States by General Foods, and was a mid-20th-century staple — and occasional punchline. (In the 1982 movie "Fast Times at Ridgemont High," a biology teacher pleads with his students, "I'm a little slow today. I just switched to Sanka, so have a heart.")

Benzene is no longer used for decaffeinating coffee because it's a known carcinogen. Instead, companies that use chemical solvents have switched to other substances, predominantly ethyl acetate and methylene chloride, although there has been some controversy about the latter because exposure to high amounts of the substance can be toxic and lead to damage of the central nervous system. The FDA has ruled that miniscule trace amounts of methylene chloride in decaf coffee are not cause for concern, and residues of more than 0.001% are prohibited.

Another method for decaffeinating coffee also originated, somewhat accidentally, in Germany. Chemist Kurt Zosel was working with supercritical carbon dioxide at the Max Planck Institute for Coal Research in Ruhr. Zosel discovered that when the gas is heated and put under a lot of pressure, it enters a supercritical state that can be useful for separating different chemical substances — including separating caffeine from coffee when it's pumped through the beans.

The chemist patented his decaffeination method in 1970; it's still widely used today. According to NPR, crude caffeine can be salvaged during the supercritical carbon dioxide decaffeination process, which is used in sodas, energy drinks and other products.

Yet another method, dubbed the Swiss Water Process, was first used commercially in the 1970s. Kastle explained that first, a batch of green coffee beans is soaked in water. That water becomes saturated with all the soluble components found in coffee — including chlorogenic acid, amino acids and sucrose; the caffeine is then filtered out with carbon. This uncaffeinated liquid, called green coffee extract, is then added to columns of new, rehydrated, green coffee beans that still have their caffeine. Kastle said that caffeine migrates from the beans to the green coffee extract as the beans and liquid seek equilibrium, until the beans are almost entirely caffeine-free."

Netflix’s $900K AI Jobs

So what are these jobs? In addition to the overall product manager one, there are five other roles with obvious machine learning responsibilities, and likely more if you were to scour the requirements and duties of others.

An engineering manager in member satisfaction ML — their recommendation engine, probably — could earn as much as $849,000, but the floor for the “market range” is $449,000. That’s where the conversation starts! An L6 research scientist in ML could earn $390,000 to $900,000, and the technical director of their ML R&D tech lab would make $450,000-$650,000. There are some L5 software engineer and research scientist positions open for a more modest $100,000-$700,000.

One comparison that was quickly made is to the average SAG member, who earns less than $30,000 from acting per year. Superficially, Netflix paying half a million to its AI researchers so that they can obsolete the actors and writers altogether is the kind of Evil Corp move we have all come to expect. But that’s not quite what’s happening here.

While I have no doubt that Netflix is screwing over its talent in numerous ways, just like every other big studio, streaming platform and production company, it’s important for those on the side of labor to ensure complaints have a sound basis — or they’ll be dismissed from the negotiating table. (...)

As a tech company, Netflix is, like every other company on Earth, exploring the capabilities of AI. As you may have guessed from the billions of dollars being invested in this sector, it’s full of promise in a lot of ways that aren’t actually connected to the controversial generative models for art, voice and writing, which for the most part have yet to demonstrate real value.

No doubt they are exploring those things too, but most companies remain extremely skeptical of generative AI for a lot of reasons. If you read the actual job descriptions, you’ll see that none actually pertain to content creation:

-You will lead requirements, design, and implementation of Metaflow product improvements…

-You will lead a team of experts in these techniques to understand how members experience titles, and how that changes their long-term assessment of their satisfaction with the Netflix service.

-…incubate and prototype concepts with the intent to eventually build a complete team to ship something new that could change the games industry and reach player audiences in new ways, as well as influencing adoption of AI technologies and tooling that are likely to level up our practices.

-…we are venturing further into exciting new innovations in personalization, discovery, experimentation, backend operations, and more, all driven by research at the frontiers of ML

-…Collect feedback and understand user needs from ML/AI practitioners and application engineers across Netflix, deriving product requirements and sizing their importance to then prioritize areas of investment.

-We are looking for an Applied Machine Learning Scientist to develop algorithms that power high quality localization at scale…Sure, the last one is likely generative dubbing, or perhaps improved subtitle translation. And this doesn’t mean Netflix isn’t working on generative stuff too. But these are the jobs we’re actually seeing advertised, and most are generic “we want to see what we can do with AI to make stuff better and more efficient.”

AI applies across countless domains, as we chronicle in our regular roundup of research. A couple weeks ago it helped find new Nasca lines! But it’s also used in image processing, noise reduction, motion capture, network traffic flow and data center power monitoring, all of which are relevant to a company like Netflix. Any company of this size that is not investing hundreds of millions in AI research is going to be left behind. If Disney or Max develops a compression algorithm that halves the bandwidth needed for good 4K video, or cracks the recommendation code, that’s a huge advantage.

So, why am I out here defending a giant corporation that clearly should be paying its writers and actors more?

Because if the unions and their supporters are going to take Netflix to task, as they should given the deplorable state of residuals and IP ownership, they can’t base their outrage on industry standard practices that are necessary for a tech company to succeed in the current era.

We don’t have to like that AI researchers are being paid half a million while an actress from a hit show a couple years back gets a check for $35. But this portion of Netflix’s inequity is, honestly, out of their control. They’re doing what is required of them there. Ask around: Anyone with serious experience in machine learning and running an outfit is among the most sought-after people in the world right now. Their salaries are grossly inflated, yes — they’re the A-listers of tech right now, and this is their moment. (...)

By all means let’s get up in arms about inequity — but if this anger is to take effect, it needs to be grounded in reality and targeted properly. Hiring an AI researcher for an extravagant salary to refine their recommendation engine isn’t the problem on its own — it’s the hypocrisy demonstrated by Netflix (and every other company doing this, probably all of them) showing that it is willing to pay some people what they’re worth, and other people as little as they can get away with.

by Devin Coldewey, TechCrunch | Read more:

Image: Frederic J. Brown/AFP/Getty Images

[ed. Nice work if you can get it. Job responsibilities evolve over time. See also: The week in AI: Generative AI spams up the web (TC).]

Saturday, July 29, 2023

Three Body Problem (Chinese Version)

[ed. Tencent Video has released an excellent Chinese serialized/subtitled version of the Three Body Problem (30 episodes), a science fiction trilogy by Cixin Liu. Considered by many to be one of the best sci-fi novels published in recent history, on par with the best works of Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, Stanislaw Lem and others (see here, here and here). A westernized version is being developed by Netflix. See also: This short summary of Three Body Problem themes (YouTube).]

Friday, July 28, 2023

Sinead O'Connor (December, 1966 - July, 2023)

I was born in Dublin town

Where there was not too much going on down

For girls whose only hope

Was not to find a man who could piss in a pot

So early I heard my first guitar

And I knew I wanted to be a big star

And I told my poor worried father

Said I ain't gonna go to school no more

'Cause see I wanna look cool and I wanna look good

With my hair slicked back and my black leather boots

Wanna stand up tall with my boobs upright

And feel real hot when the makeup's nice

I get sexy underneath the lights

Like I wanna fuck every man in sight

Baby come home with me tonight

Make you feel good make you feel all right

I'm going away to London

I got myself a big fat plan

I'm gonna be a singer in a rock 'n' roll band

I'm gonna change everything I can

Wasn't born for no marrying

Wanna make my own living singing

Strong independent pagan woman singing

And I feel real cool and I feel real good

Got my hair shaved off and my black thigh boots

I stand up tall with my pride upright

I feel real hot when the makeup's nice

I get sexy underneath them lights

Like I wanna fuck every man in sight

Baby come home with me tonight

Make you feel good make you feel all right

I'm glad I came here to London

I've myself some big fat fun

And I have even made some mon'

I got the most angelic son

My baby daughter is golden

And I do what I like for fun

And I'm happy in my prime

Daddy I'm fine

Daddy I'm fine

Daddy I'm fine

Daddy I'm fine

Daddy I'm fine

Daddy I love you

Thursday, July 27, 2023

The Number of Songs in the World Doubled Yesterday

An artificial intelligence company in Delaware boasted, in a press release, that it had created 100 million new songs. That’s roughly equivalent to the entire catalog of music available on Spotify.

It took thousands of years of human creativity to make the first 100 million songs. But an AI bot matched that effort in a flash.

The company notes that this adds up to 4.8 million hours of creativity.

And we’re only at the start of the AI revolution.

The goal here is infinity. Until this week, I didn’t think infinity could be an artistic goal—or even a guideline—but that’s precisely the aim of Mubert (the name of the company behind this breakthrough).

The company’s CEO—also named Mubert—declared:

“Mubert allows for the generation of an unlimited amount of music of any duration and any genre.”At first, I thought this might be a prank. Even that name—Mubert—sounds like a parody of Mozart. I was actually hoping that the CEO’s full name was Wolfgang Amadeus Mubert.

No dice. The boss at this startup is Alex Mubert, a software engineer living in Dubai (according to his LinkedIn profile). That same source tells me that he once studied bass at Jazz College.

It’s possible that years from now, the history of music will be divided into two phases: Before Mubert and After Mubert. We are blessed to live at the dawn of this new era of musical abundance.

Mubert isn’t alone—many others are chasing after this same Nirvana of never-ending playlists. A few weeks ago, another AI company called Boomy (who comes up with these names?) announced that it had created more than 14 million AI tracks.

Spotify responded by pulling these songs from its platform, but Spotify also seems to have a love affair with AI music, especially if it potentially enriches the company at the expense of human composers.

But Mubert has one huge advantage.

The company trained its AI on music obtained legally for that purpose. This means Mubert may be invincible to the copyright litigation that threatens to kill other areas of AI creation.

That’s a huge competitive advantage in the music business right now, where lawyers run the show with more bravado than Barnum, Bailey and the Ringling Brothers put together. You could even put Mubert on the stand in a trial, and he or it (depending on which Mubert you swear in) has an airtight alibi for any plagiarism claim. The AI never heard a song without legal permission.

Not even Taylor Swift or Ed Sheeran possess that super power. (...)

Something broke on the levee, and AI songs are pouring out in torrents, threatening to wash away everything else.

Now, I can’t claim to have listened to all 100 million of these songs. But I’ve heard enough AI music to realize how lousy it is.

And if the first 100 million AI songs suck, my enthusiasm for the next 100 million is nil. That’s how things work in creative fields—people judge you by your track record.

Back in February, I warned of a mind-numbing oversupply of content in my “State of the Culture 2023” address. As many of you know, I hate the word content, when it’s used to describe human creativity. But it is the perfect term to describe the output of the AI sausage factories that are making inroads everywhere in the culture.

We don’t need more supply in music, or other creative fields. The real shortage is demand. And the ultimate shortage is genius, which usually goes under names like Mozart and Beethoven, not Mobert and Boomy.

Somebody needs to remind Mubert the AI Bot (or Mubert the CEO) that in the music business you get an audition, and you play your best stuff first. If the first couple songs don’t sound good, you don’t get another chance.

So here’s my challenge to Mubert. Quit bragging about your 100 million tracks. Just pick the best two or three, and let us listen to them—and make up our minds.

I probably sound flippant here.

And, it’s true, I have a tendency to laugh at the boastful claims being made for improving the arts with AI technology. There’s something ridiculous about this music—or, to put it more clearly, there’s something ridiculous about the mismatch between the music itself and the claims made for it.

But I really need to emphasize that this is no laughing matter. The larger picture here is ominous:

- For the first time in history, the most powerful and wealthy companies are all tech global players with consumer-facing platforms.

- Every one of them is now obsessed with AI as a profit-generating opportunity.

- The various AI projects they’re pursuing are all different, but they have one thing in common: They involve flooding the culture with torrents of AI garbage—the metrics are all quantitative, not qualitative (because, hey, that’s how they roll).

- Quality checks are actually viewed as hindrances. In the mad gold rush mentality of the AI revolution, quality slows things down—so even the most basic safeguards are ditched or ignored.

- But genuine creativity operates in the qualitative realm. In that sphere, numbers are meaningless. Mozart’s Requiem or the The White Album or other works of that sort can’t be replaced with 100 million AI tracks—numbers don’t work like that.

- The more garbage you dump into our polluted culture, the more obvious this becomes.

The Curious Personality Changes of Older Age

Psychologists used to follow the same line of thinking: After young adulthood, people tend to settle into themselves, and personality, though not immutable, usually becomes stabler as people age. And that’s true—until a certain point. More recent studies suggest that something unexpected happens to many people as they reach and pass their 60s: Their personality starts changing again.

This trend is probably observed in older populations in part because older adults are more likely to experience brain changes such as cognitive impairment and dementia. But some researchers don’t believe the phenomenon is fully explained by those factors. People’s personality can morph in response to their circumstances, helping them shift priorities, come to terms with loss, and acclimate to a changing life. These developments illuminate what personality really is: not a permanent state but an adaptive way of being. And on a societal level, personality changes might tell us something about the conditions that older adults face.

Psychologists have identified certain major, measurable personality traits called the “Big Five”: agreeableness, conscientiousness, extroversion, openness to experience, and neuroticism. And they can track how those traits increase or decrease in a group over time. To the surprise of many in the field, those kinds of studies are revealing that the strongest personality changes tend to happen before age 30—and after 60. In that phase of later adulthood, people seem to decrease, on average, in openness to experience, conscientiousness, and extroversion—particularly a subcategory of extroversion called “social vitality.” And neuroticism tends to increase, especially closer to the end of one’s life.

We can’t say with certainty what factors are driving these shifts, but a few theories exist. One possibility is that personality is shaped by specific life events that tend to happen in older age: retirement, empty nesting, widowhood. But such milestones, it turns out, aren’t very reliable sources of change; they affect some people deeply and others not at all. Any one event could mean many different things, depending on its context. Jenny Wagner, a psychologist at the University of Hamburg, in Germany, gave me some examples. Losing a partner could be a tremendous loss, but for some it could be a bit of a relief at the same time—say, for someone who’s been caring for their ailing spouse for years. Retirement is the same: Where one person might be jumping from book club to vacation, another might be hobbled by lack of income, forced to move away from friends to a cheaper part of town.

At any age, life events can affect people differently. But in older adulthood particularly, researchers told me, people’s daily realities vary wildly, so factors like health and social support are probably better predictors of personality change. “What you really want to know,” Wiebke Bleidorn, a personality psychologist at the University of Zurich, told me, “is What are people’s lives like?” If someone is no longer strong enough to go to dinner parties every week, they might grow less extroverted; if someone needs to be more careful of physical dangers like falling, it makes sense that they’d grow more neurotic.

The idea that people might change who they are—really change, in a deep and even lasting way—in response to their circumstances might seem surprising. Many of us think of personality not as a set of dials we can modulate strategically but as something more akin to a hand of cards you’ve been dealt. In truth, personality can likely be nudged by our environment and our relationships—our commitments to other people, and their expectations for us—at any age. But before older adulthood, people might commonly be less pressed to change themselves; they can usually change their habits and environments instead. Brent Roberts, a psychology professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, told me that “we construct our world to avoid” personality change. But if you can’t take yourself to the grocery store, much less move to a different city, you might need to adapt. Once you lose control over elements of your life, Bleidorn said, you may alter your personality instead.

Granted, old-age personality changes don’t always result from a sense of helplessness or an endlessly shrinking life. Research has shown that when people get older, they commonly recalibrate their goals; though they might be doing less, they tend to prioritize what they find meaningful and really appreciate it. A decline in openness to experience, then, could reflect someone relishing their routine rather than seeking new thrills; a decline in extroversion could indicate that they’re satisfied spending time with the people they already love. That may involve adjusting to what they can’t control, but it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re reacting to a bad life—just a different one. [ed. See article below]

[ed. Sometimes old people drive me nuts, and I'm old myself. One thing for sure: if you had personality quirks before, they'll only get more pronounced later in life. If people do change it's probably more related to love and loss. As one gets older, the people and things you've loved and lost pile up... parents, family, friends, lovers, partners, health, vitality, life experiences. All gone, or fast receding. So 'recalibrating' likely means embracing memories more than future plans. Plus, the arc of your life becomes clearer.]

The Mind Is Willing, So the Body Doesn’t Have Much Choice

Duggan, 74, the proud owner of an artificial hip, marveled at the sheer number of titanium body parts in the locker room. He gestured toward Mitch Boriskin, who was wiggling into a pair of skates along the opposite wall.

Boriskin, 70, smiled. “Two fake knees, a spinal cord stimulator, 25 surgeries,” he began, as if reciting a box score.

“And one lobotomy,” Duggan interjected, as laughter rippled across the room.

All that titanium, at least, was being put to good use. Their team, the Oregon Old Growth, had joined dozens of others from around North America to compete this month at the Snoopy Senior hockey tournament in Santa Rosa, Calif., about 60 miles north of San Francisco.

The tournament has become a summertime ritual for hundreds of recreational players — all of them between 40 and 90 years old — who gather each year at Redwood Empire Ice Arena, where Charles M. Schulz, the creator of the “Peanuts” comic strip and a lifelong hockey fanatic, founded the event in 1975.

By now, everyone knows what to expect: The skating is slow, the wisecracks whiz by fast and the laughter flows as freely as the beer.

“If you like paint drying, you will be riveted,” said Larry Meredith, 82, the captain of the Berkeley Bears, a team in the tournament’s 70-plus division. (...).

“You don’t quit because you get old, you get old because you quit,” said Rich Haskell, 86, a player from New Port Richey, Fla. “A friend of mine died a couple years ago. He played hockey in the morning, died at night. You can’t do it better than that.”

The tournament has the unbent feel of a week-and-a-half long summer camp. Camper vans and R.V.s crowd the arena parking lot, where players drink beer, grill meat and fraternize between games.

The squad names this year — California Antiques, Michigan Oldtimers, Seattle Seniles, and Colorado Fading Stars, to name a few — nodded at players’ advanced age and evolved sense of humor.

“We used to just be the Colorado Stars,” said Rich Maslow, 74, the team’s goalie. “But then we turned 70.”

Maslow and his teammates were scheduled to play that day at 6:30 a.m., the earliest slot, which meant they had to assemble before sunrise.

“We all have to get up at 5:30 to pee anyway, so we might as well play some hockey,” said Craig Kocian, 78, of Arvada, Colo., as they dressed for the game.

Kocian described himself as having “adult onset hockey syndrome.” But many other participants began playing when they were children and let the game weave itself through the decades of their lives. (...)

“It’s part of who I am, and that feeling is really powerful,” Meredith said about playing hockey. “Maybe that’s why I hang on, because it harkens back to going to a rink, smelling those smells that you can only find in an indoor ice rink, those hockey smells.”

Schulz was the same way. He ate breakfast and lunch at the rink, which he had built and opened in 1969. Spending most days grinding away at the drawing board, he saw his Tuesday night games as something of a spiritual salve.

“He used to say, ‘It’s the only thing that gives me pleasure,’ ” said Jean Schulz, his widow.

He played until he died, at the age of 77, in 2000. Many players said they would like to do the same. (...)

After their early morning game, the Fading Stars came off the ice and stripped away their gear. Out came a case of Coors Light. It was 7:40 a.m. Noticing the beer company’s logo on the team’s sweaters, a visitor asked if it was a sponsor.

“The only sponsorship we’re looking for is Viagra,” said Murray Platt, 68, of Denver.

Also grabbing a cold one was Dave McCay, 72, of Denver, who scored four goals in the team’s opening game, sprained an ankle in the second and arrived for the third in a walking boot.

That leg had given him trouble before — he held up a photo showing 12 screws, a steel rod and a plate in it — and his wife had already begun gently questioning his priorities. But slowing down has not crossed his mind.

“I’m convinced this gives you a better quality of life,” McCay said, leaning on a pair of crutches, “even if you have to limp around a little bit.”

Wednesday, July 26, 2023

The 21st-Century Shakedown of Restaurants

No, wait. This isn’t a joke. This is a 21st-century shakedown.

Here is how it works: An influencer walks into a restaurant to collect an evening’s worth of free food and drink, having promised to create social media content extolling the restaurant’s virtues. The influencer then orders far more than the agreed amount and walks away from the check for the balance or fails to tip or fails to post or all of the above. And the owners are left feeling conned.

The swap of food for eyeballs is nothing new in our digital age; businesses can fail from a lack of exposure. But the entitled disregard — with emboldened influencers making outsize demands but not always fulfilling their end of the bargain — is a more recent phenomenon. They have come to realize that they have all the power, as defined by the number of followers they have on TikTok or YouTube or Instagram. It’s an influence seller’s market, defined by whatever the traffic will bear.

In a business without boundaries, anything goes. Brian Bornemann, the chef and a co-owner of the restaurants Crudo e Nudo and Isla in Santa Monica, Calif., said that while there are reliable influencers, the “lower echelons” see a free meal as a way to build their personal brands. And the most entrepreneurial influencers, whether they have sophisticated skills or merely a prospector’s zeal, offer an ascending roster of fee-based services. Exposure packages can cost upwards of $1,000 for a prescribed number of Instagram stories, posts and a professionally made video, sometimes with performance bonuses tied to views.

Influencer content is lifestyle advertising, selling a quick, aspirational message that has more in common with a fashion ad than with reality. Visit this restaurant, a post implies, and your life will be as much fun as mine. Status is defined by popularity rather than by expertise or by character, and credible, food-savvy comments can get lost in the increasing din.

The opportunists — who give new meaning to the term “grab and go” — aren’t good for restaurants, which are trying to get back on their feet after the pandemic. They aren’t good for the rest of us, either, because they make the already dubious content flooding our feeds even more suspect. The more we rely on influencer posts, the more our critical faculties shrink, because often there’s no depth, no context, no reporting, nothing beyond the surface image of fun, and we can’t tell whom to trust. (...)

Journalists and influencers are not the same species, but we intersect at one point on the graph — we provide information — making it easy to get us mixed up. Welcoming influencers into your dining room can seem easier, at first glance, because they’re looking for good news: All you have to do is feed and water them, and with luck, they go away to post nice photos along with a little copy.

That initial ease comes at a price. Fear and imagination are a potent mix, and wary restaurateurs worry about retaliation if food influencers don’t get what they want: criticism of food that they might have said tasted better if it had been free, complaints about nonexistent bad service or a bottle of wine that the group drained dry before judging it to be off.

Or they can stiff a restaurant. I hear first-tier influencers sharpening their cutlery to defend their honor, but numerous restaurateurs tell me that dealing with the second tier is a constant challenge. (...)

Mr. Bornemann tells influencers he hasn’t worked with to come in on their own dime, once, before he’ll do business. “If they balk,” he said, “they’re bogus.”

Owners can take on the additional job of trying to verify influencer numbers because there are many ways to artificially boost follower counts. If influencers reach out to say they enjoyed a meal at a restaurant and would be happy to return and post in exchange for a freebie, owners can ask for the date of the initial visit to see if there’s a credit card charge on file or check the menu to see if the items the influencers loved were offered on the night in question.

Some restaurants reject all requests below a minimum follower threshold, and some simply refuse to engage. But it takes nerve to opt out.

by Karen Stabiner, NY Times | Read more:

"Deanna Giulietti is not in the actors’ union, but she turned down $28,000 last week because of its strike.

Ms. Giulietti, a 29-year-old content creator with 1.8 million TikTok followers, had received an offer to promote the new season of Hulu’s hit show “Only Murders in the Building.”

But SAG-AFTRA, as the union is known, recently issued rules stating that any influencer who engages in promotion for one of the Hollywood studios the actors are striking against will be ineligible for membership. (Disney is the majority owner of Hulu.) That gave Ms. Giulietti, who also acts and aspires to one day join the union, reason enough to decline the offer from Influential, a marketing agency working with Hulu.

The union’s rule is part of a variety of aggressive tactics that hit at a pivotal moment for Hollywood labor and shows its desire to assert itself in a new era and with a different, mostly younger wave of creative talent.

“I want to be in these Netflix shows, I want to be in the Hulu shows, but we’re standing by the writers, we’re standing by SAG,” Ms. Giulietti said. “People write me off whenever I say I’m an influencer, and I’m like, ‘No, I really feel I could be making the difference here.’”

That difference comes at a cost. In addition to the Hulu deal, Ms. Giulietti recently declined a $5,000 offer from the app TodayTix to promote the Searchlight Pictures movie “Theater Camp.” (Disney also owns Searchlight.) She said she was living at home with her parents in Cheshire, Conn., and putting off renting an apartment in New York City while she saw how the strike — which, along with a writers’ strike, could go on for months — would affect her income."