What the global celebrity never does is arrive alone with a dozen instruments and spend the day wandering the shoot location playing flute.

***

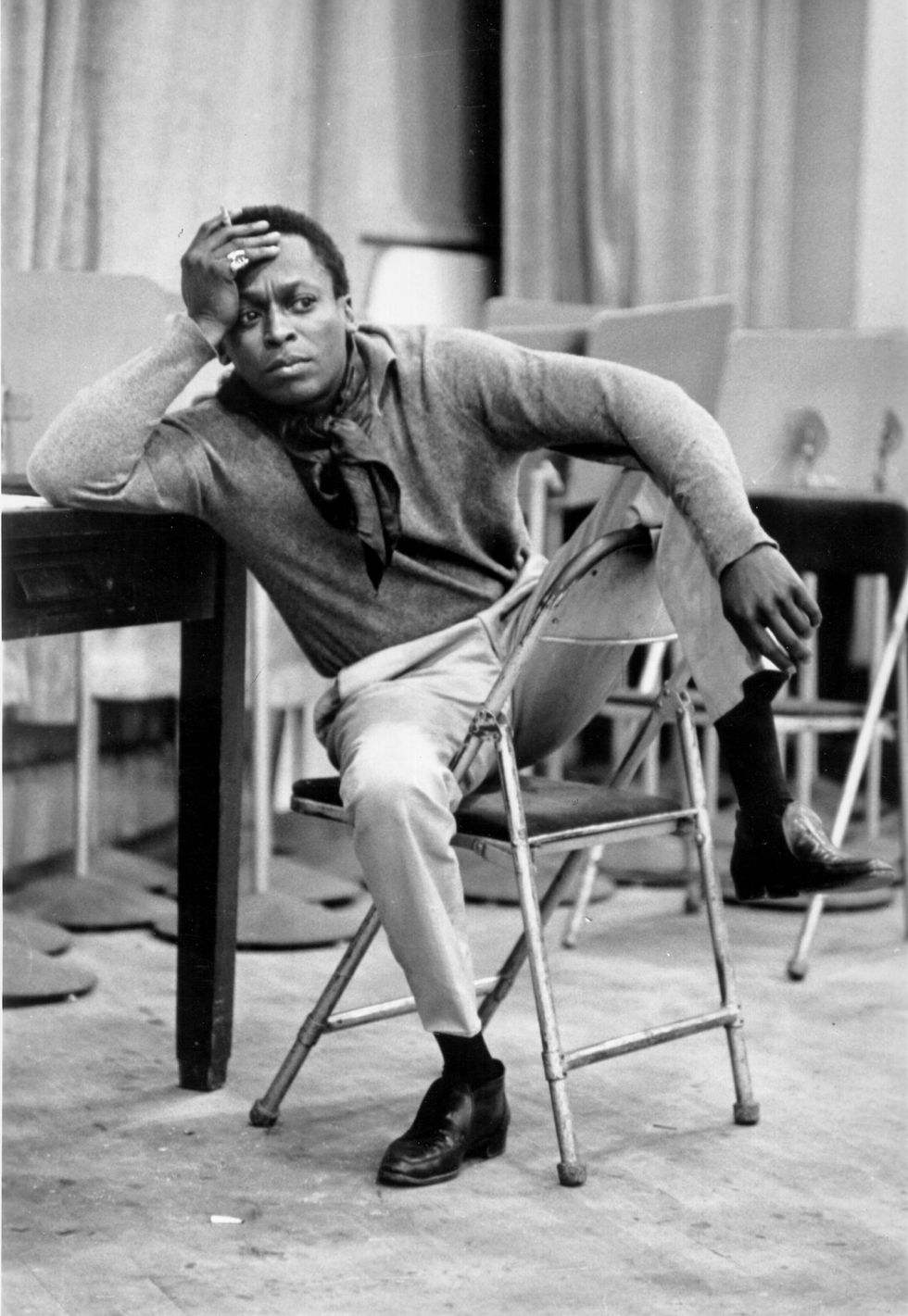

On this afternoon, André 3000, one of the most singular and best-dressed musicians of all time, is only days away from releasing New Blue Sun, a solo album of flute music — flutes being so much his thing at the moment, he’s brought one to Gjelina, one of Venice’s more hyped restaurants, where we are having lunch. It is carved from dark wood, the length of his arm, ancient-looking. Only a couple minutes later, he starts playing a string of soft notes, in the manner of a breathy bird. Soon, diners’ heads are swiveling to locate the sound, maybe to see if Pan, the Greek god of shepherds, has joined us for upscale pizza. This is probably obvious, but no one else in the restaurant is playing flute over their upscale pizza.André has on what he describes as his daily uniform: vintage overalls, a beanie, and clean Nikes. His sunglasses are brown, lightly tinted. Under his overalls, he wears a long-sleeved camouflage shirt. “I have 40 of these shirts. I wake up in the morning and put the same thing on.” The look is duck hunter meets farmhand meets sneakerhead. Have you ever met someone and wanted to buy their look in entirety and throw it on right there? I ask if such a thing were possible. He explains he’s just gotten back from Amsterdam where he was developing a new brand of his own, of similar workwear, coming soon. (André had a line in the late aughts called Benjamin Bixby, with clothes that recalled early Ivy League prep.) “Whenever I’m on the street, at least for a month, whenever I see someone with overalls on, they’re going to get a free pair,” André says. “Because I know they’re overall lovers. It takes a certain person to wear overalls. They’re like grown-people baby clothes. They feel very comfortable — that’s why I love them.”

If anybody was comfortable in their own skin, it’s André 3000. Over the years, just going by style alone, André has dressed like a Gatsby dandy, a Scottish lord, and a streetwear prince. Recently he had been on the street a lot, playing the flute while wandering the globe — so much that a meme grew around it, like Bill Murray being spotted at frat parties, where somebody would take a picture of André playing flute in a coffee shop or in an airport security line. “I was in Philadelphia,” he says, “and someone came up to me. He was like, ‘You know, it’s a game now.’” A game asking not only where in the world was André 3000 these days, à la Where’s Waldo, but what the hell was this famous rapper doing walking around with a flute?

An hour earlier, driving to lunch and listening to an advance copy of New Blue Sun in my car, I’d been wondering the same thing. I hadn’t known what to expect; I didn’t have any context. (“No context?” André says, when I confess as much, and starts laughing. “No context? Wow.”) If anything, I expected a rap album because that’s what André 3000 was known for: being half of OutKast, the Atlanta duo, the legendary hip-hop group. I mean, I wondered if I’d been sent the wrong record. Just a few minutes into it, all shimmering cymbals and keyboard tones, then a warbling, digital flute, my mind was floundering, stretching hard for comparisons. Was this jazz or New Age? Was it what shamans played during ayahuasca ceremonies or what they piped into massage chambers at the Maui Four Seasons?

Were these songs or something else?

“I don’t even call them songs,” André says, smiling at my confusion. “They’re almost like formations, like you’re hearing something as it’s happening. It’s a living, breathing, sound exploration.”

He stares at me intently across the table, and I remember the first track’s title: “I swear, I Really Wanted To Make A ‘Rap’ Album But This Is Literally The Way The Wind Blew Me This Time.” The sub-text suggests: Put aside your preconceived notions and listen closely, I’ll tell you exactly where I’m at.

So, I start to listen.

In 2003, André 3000 had the world at his feet. He and his OutKast partner, Big Boi, born Antwan André Patton, had produced four albums that defined a style — precise lyricism meets updated funk meets Afrofuturism meets avant-soul — and basically launched Southern hip-hop at a time when any rap that wasn’t from New York or Los Angeles was dismissed. And then, with their fifth album, Speakerboxxx/The Love Below, they created a global juggernaut: the best-selling rap album in history, a record that went 13 times platinum and won three Grammys in 2004 (Album of the Year, Best Rap Album, and Best Urban/Alternative Performance) on the back of two number-one singles, “Hey Ya!” and “The Way You Move,” which have been played at half the world’s weddings ever since.

At that Grammy Awards ceremony, André performed onstage in fluorescent green (buckskin leggings?), but he could’ve worn anything. He could’ve done anything.

What he did was basically disappear from the public eye, except for occasional moments when people posted snapshots of him on social media.

And now, 20 years later, he is back — with a woodwind album.

André 3000 doesn’t read music, he doesn’t know keys, he doesn’t know chords — but he knows what he’s doing. He was born André Lauren Benjamin in 1975, in Atlanta, Georgia. As a kid, he thought he’d become a visual artist. “And then I discovered rap videos.” He met Big Boi in high school. OutKast’s debut album, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, came out in 1994 and went on to establish Atlanta as a viable alternative to the East Coast/West Coast rivalry — based partly on André’s extremely studied, meticulously composed verses. “I’m not a freestyle rapper, right?” he says. “I architecturally made those verses bar by bar.” (...)

André, over time, has resisted such calcification. After OutKast, he helped to produce and voice Class of 3000, an animated show for Cartoon Network. He’s acted in dozens of films and TV episodes, including the starring role in 2013’s Jimi Hendrix biopic Jimi: All Is by My Side; a scene-stealing turn in French auteur Claire Denis’ 2018 sci-fi High Life; and a critically lauded part, alongside Michelle Williams, in 2022’s Showing Up. Still, there’s also been rapping: appearing on remixes, covering Amy Winehouse’s “Back to Black” with Beyoncé, and doing a guest verse for Drake. The point is, the longer we speak, it seems as though André’s part in OutKast is a figment of a former life.

His present life, at least until recently, hadn’t necessarily been easy. In 2019, André appeared on the podcast Broken Record with super-producer Rick Rubin and talked about being diagnosed as an adult with anxiety and hypersensitivity. “Any little thing I put out, it’s instantly attacked, not in a good or bad way. People nitpick it with a fine-tooth comb. ‘Oh, he said that word!’ And that’s not a great place to create from and it makes you draw back. Maybe I don’t have the confidence that I want, or the space to experiment like I used to.” But that was four years ago. And clearly, releasing his first solo album — no bars, all flute — hints that his confidence has been re-discovered. I suggest to André the new album points toward a new direction, particularly since it isn’t — different from his rap work — carefully planned or composed. “Freedom is happening,” he says. “We listened to each other. Sometimes the melodies you’re hearing, I was making them up on the spot or I was responding on the spot. That’s the value of this album, that it’s fully alive. It wasn’t planned.” If anything, he worried how the spontaneity would be received by listeners. “I’m scared. I don’t want to troll people. New André 3000 album coming out! And you play it — like, man, what the fuck? On the packaging, there’s a graphic that says ‘Warning: no bars.’ So it completely lets you know what you’re getting into before you get into it. I don’t want people to feel like I’m playing with them. That could ruin the whole thing.”

A moment later, he says, “It’s very intimate. With rap, with an OutKast song, people know the beat, and I can hide behind the beat. With this, you can’t hide behind anything.” (...)

So, where is André 3000 now, literally at this present moment? I mean, other song titles on the album suggest what he’s been up to during his time away from rap — “That Night In Hawaii When I Turned Into A Panther And Started Making These Low Register Purring Tones That I Couldn’t Control … Sh¥t Was Wild,” or “The Slang Word P(*)ssy Rolls Off The Tongue With Far Better Ease Than The Proper Word Vagina . Do You Agree?” Maybe the more interesting question is what is André now? He’s a meme, he’s a man, he’s a musician. He’s a rapper, he’s a flautist, he’s a style star. I put it to him: Does he miss rapping? “I do,” he says. “I would love to make a rap album. I just think it’d be an awesome challenge to do a fire-ass album at 48 years old. That’s probably one of the hardest things to do! I would love to do that.” Maybe that’s what’s coming next, I offer. “Possibly! That’s the cool thing about my whole ride. It really is a ride.”

If anybody was comfortable in their own skin, it’s André 3000. Over the years, just going by style alone, André has dressed like a Gatsby dandy, a Scottish lord, and a streetwear prince. Recently he had been on the street a lot, playing the flute while wandering the globe — so much that a meme grew around it, like Bill Murray being spotted at frat parties, where somebody would take a picture of André playing flute in a coffee shop or in an airport security line. “I was in Philadelphia,” he says, “and someone came up to me. He was like, ‘You know, it’s a game now.’” A game asking not only where in the world was André 3000 these days, à la Where’s Waldo, but what the hell was this famous rapper doing walking around with a flute?

An hour earlier, driving to lunch and listening to an advance copy of New Blue Sun in my car, I’d been wondering the same thing. I hadn’t known what to expect; I didn’t have any context. (“No context?” André says, when I confess as much, and starts laughing. “No context? Wow.”) If anything, I expected a rap album because that’s what André 3000 was known for: being half of OutKast, the Atlanta duo, the legendary hip-hop group. I mean, I wondered if I’d been sent the wrong record. Just a few minutes into it, all shimmering cymbals and keyboard tones, then a warbling, digital flute, my mind was floundering, stretching hard for comparisons. Was this jazz or New Age? Was it what shamans played during ayahuasca ceremonies or what they piped into massage chambers at the Maui Four Seasons?

Were these songs or something else?

“I don’t even call them songs,” André says, smiling at my confusion. “They’re almost like formations, like you’re hearing something as it’s happening. It’s a living, breathing, sound exploration.”

He stares at me intently across the table, and I remember the first track’s title: “I swear, I Really Wanted To Make A ‘Rap’ Album But This Is Literally The Way The Wind Blew Me This Time.” The sub-text suggests: Put aside your preconceived notions and listen closely, I’ll tell you exactly where I’m at.

So, I start to listen.

In 2003, André 3000 had the world at his feet. He and his OutKast partner, Big Boi, born Antwan André Patton, had produced four albums that defined a style — precise lyricism meets updated funk meets Afrofuturism meets avant-soul — and basically launched Southern hip-hop at a time when any rap that wasn’t from New York or Los Angeles was dismissed. And then, with their fifth album, Speakerboxxx/The Love Below, they created a global juggernaut: the best-selling rap album in history, a record that went 13 times platinum and won three Grammys in 2004 (Album of the Year, Best Rap Album, and Best Urban/Alternative Performance) on the back of two number-one singles, “Hey Ya!” and “The Way You Move,” which have been played at half the world’s weddings ever since.

At that Grammy Awards ceremony, André performed onstage in fluorescent green (buckskin leggings?), but he could’ve worn anything. He could’ve done anything.

What he did was basically disappear from the public eye, except for occasional moments when people posted snapshots of him on social media.

And now, 20 years later, he is back — with a woodwind album.

André 3000 doesn’t read music, he doesn’t know keys, he doesn’t know chords — but he knows what he’s doing. He was born André Lauren Benjamin in 1975, in Atlanta, Georgia. As a kid, he thought he’d become a visual artist. “And then I discovered rap videos.” He met Big Boi in high school. OutKast’s debut album, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, came out in 1994 and went on to establish Atlanta as a viable alternative to the East Coast/West Coast rivalry — based partly on André’s extremely studied, meticulously composed verses. “I’m not a freestyle rapper, right?” he says. “I architecturally made those verses bar by bar.” (...)

André, over time, has resisted such calcification. After OutKast, he helped to produce and voice Class of 3000, an animated show for Cartoon Network. He’s acted in dozens of films and TV episodes, including the starring role in 2013’s Jimi Hendrix biopic Jimi: All Is by My Side; a scene-stealing turn in French auteur Claire Denis’ 2018 sci-fi High Life; and a critically lauded part, alongside Michelle Williams, in 2022’s Showing Up. Still, there’s also been rapping: appearing on remixes, covering Amy Winehouse’s “Back to Black” with Beyoncé, and doing a guest verse for Drake. The point is, the longer we speak, it seems as though André’s part in OutKast is a figment of a former life.

His present life, at least until recently, hadn’t necessarily been easy. In 2019, André appeared on the podcast Broken Record with super-producer Rick Rubin and talked about being diagnosed as an adult with anxiety and hypersensitivity. “Any little thing I put out, it’s instantly attacked, not in a good or bad way. People nitpick it with a fine-tooth comb. ‘Oh, he said that word!’ And that’s not a great place to create from and it makes you draw back. Maybe I don’t have the confidence that I want, or the space to experiment like I used to.” But that was four years ago. And clearly, releasing his first solo album — no bars, all flute — hints that his confidence has been re-discovered. I suggest to André the new album points toward a new direction, particularly since it isn’t — different from his rap work — carefully planned or composed. “Freedom is happening,” he says. “We listened to each other. Sometimes the melodies you’re hearing, I was making them up on the spot or I was responding on the spot. That’s the value of this album, that it’s fully alive. It wasn’t planned.” If anything, he worried how the spontaneity would be received by listeners. “I’m scared. I don’t want to troll people. New André 3000 album coming out! And you play it — like, man, what the fuck? On the packaging, there’s a graphic that says ‘Warning: no bars.’ So it completely lets you know what you’re getting into before you get into it. I don’t want people to feel like I’m playing with them. That could ruin the whole thing.”

A moment later, he says, “It’s very intimate. With rap, with an OutKast song, people know the beat, and I can hide behind the beat. With this, you can’t hide behind anything.” (...)

So, where is André 3000 now, literally at this present moment? I mean, other song titles on the album suggest what he’s been up to during his time away from rap — “That Night In Hawaii When I Turned Into A Panther And Started Making These Low Register Purring Tones That I Couldn’t Control … Sh¥t Was Wild,” or “The Slang Word P(*)ssy Rolls Off The Tongue With Far Better Ease Than The Proper Word Vagina . Do You Agree?” Maybe the more interesting question is what is André now? He’s a meme, he’s a man, he’s a musician. He’s a rapper, he’s a flautist, he’s a style star. I put it to him: Does he miss rapping? “I do,” he says. “I would love to make a rap album. I just think it’d be an awesome challenge to do a fire-ass album at 48 years old. That’s probably one of the hardest things to do! I would love to do that.” Maybe that’s what’s coming next, I offer. “Possibly! That’s the cool thing about my whole ride. It really is a ride.”

by Rosecrans Baldwin, Highsnobiety | Read more:

[ed. New Blue Sun album in full here.]