[ed. As a followup to Ezra Klein's excellent interview with Sen. Brian Schatz of Hawaii (Democrats Need a Better Answer on Affordability. Here's One), which echos many of these themes.]

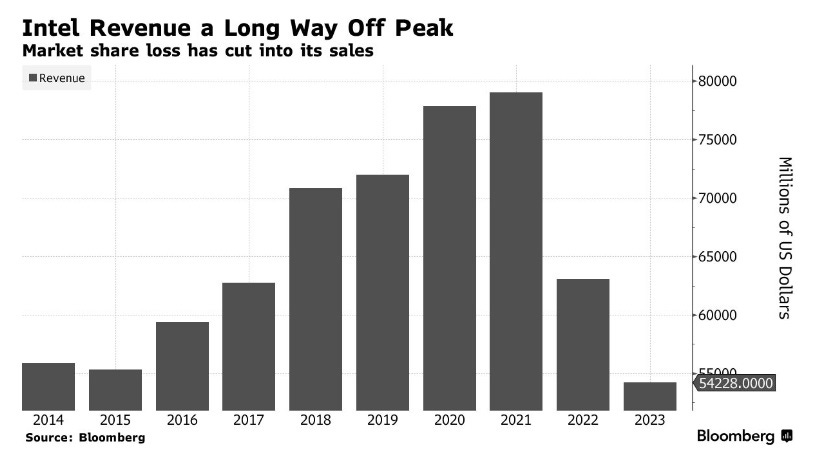

Intel stock took a huge nosedive today, losing over a quarter of its value. That’s only top of a big long-term decline since 2021. The company is worth less than a third of what it was at its peak in 2021:

The trigger for today’s decline was Intel’s announcement that it was going to going to cut 15% of its workforce and suspend dividend payments to shareholders. The longer-term drop is related to Intel’s falling revenue, which has plummeted since 2021:

Source: Bloomberg

The long-term story of Intel’s woes is by now well-known. The company grew fat and complacent from relying on its old line of business — supplying ever-better CPUs to server farms — and kept missing new markets and new business models as a result. TSMC’s foundry business proved more efficient than Intel at pushing the boundaries of chip manufacturing — using EUV lithography tools that Intel itself paid to invent, and then ended up not using. NVidia became the master of designing GPUs for AI, while a bunch of other companies like ARM and Samsung mastered low-power smartphone processors. Intel suffered from a classic case of Clay Christensen-style disruption.

On top of that, several short term factors are weighing on Intel. The post-pandemic chip shortage turned into a glut, slamming Intel’s sales and profits. U.S. export controls on China cut off Intel’s sales to Huawei.

Some commentators, seeing Intel’s woes, are rushing to declare this a failure of industrial policy. For example, here’s the WSJ editorial board:

In other bad industrial policy news, Bloomberg reported this week that Intel is planning to cut thousands of additional jobs. This would be the chip maker’s third large workforce reduction since Congress passed the $280 billion chips subsidy bill that CEO Patrick Gelsinger lobbied for. Intel has been awarded $8.5 billion in grants and up to $11 billion in loans to expand U.S. manufacturing production.At the New York Post, Stephen Moore and Phil Kerpen declare that “Biden-Harris wasted $8.5 billion in taxpayer money to lose 15,000 jobs at Intel”.

While chasing subsidies, Intel missed out on the AI boom, which has cost it dearly as competitors surge ahead. Now it’s playing catch-up. When government steers capital, companies sometimes get distracted and drive into a cul-de-sac.

Now, spending on Intel might indeed turn out to be a waste — someday. But it’s pretty ludicrous to say that Intel’s cost-cutting moves and stock price drops reflect the failure of CHIPS Act subsidies. The $8.5 billion in subsidies to Intel were announced in March 2024, in a non-binding preliminary memorandum. It is now August 2024, less than five months after that announcement. That means it’s very possible that zero dollars have actually been disbursed to Intel so far. Certainly, the majority of the subsidy money remains unspent.

It’s a little bit silly to criticize the results of a policy that hasn’t even been implemented yet.

Meanwhile, Intel’s turnaround plans — including a foundry business like TSMC’s and investments in AI chips — are still in the early stages. One reason profits have fallen at Intel is that it’s investing heavily. Bloomberg reports:

The company reports revenues divided between product groups and its manufacturing operations, with factories undergoing a massive upgrade and a build-out program that’s weighing heavily on profits…Revenue is improving at what [Intel] calls its Foundry unit, gaining 4% from a year earlier to $4.32 billion.Furthermore, Intel’s suspension of a dividend signals that it’s planning to invest its earnings in its own business, rather than returning cash to shareholders. Paying dividends is what companies do when they don’t have ways to profitably reinvest the money; this is why growth stocks don’t tend to pay dividends. This is just Corporate Finance 101.

And Intel’s job cuts, painful as they are for the workers affected, are a cost-cutting move that will free up more cash to invest in the company’s recovery plan. Whether that plan will succeed isn’t clear yet, but if you were going to turn a company like Intel around, this is probably how you’d start.

Steve Glinert (a previous Noahpinion guest contributor) has a good thread where he acknowledges Intel’s missteps and challenges, but expresses frustration with the short-termism implicit in the current round of doomsaying:

The rush to declare Intel’s struggles a failure of industrial policy is emblematic of the crippling short-termist mindset that America has allowed to set over the past few decades. It’s the same brain worm that led the same people to declare Obama’s cleantech loan programs a failure because of Solyndra, when those same loan programs boosted Tesla to become the world leader in electric vehicles — with a market cap worth far more than every penny the U.S. government spent on the entire loan program.

Industrial policy takes time. If you think that just announcing some subsidies, without even writing the checks, should be enough to boost a company like Intel to world domination within five months, you’re living in a fantasy land of your own creation. I don’t know whether or not Intel will turn itself around, but if the doomsaying of the WSJ’s editorial board represents all the patience America can muster, we might as well resign ourselves to living in the Chinese Century.

2. What’s wrong with Canada’s economy?

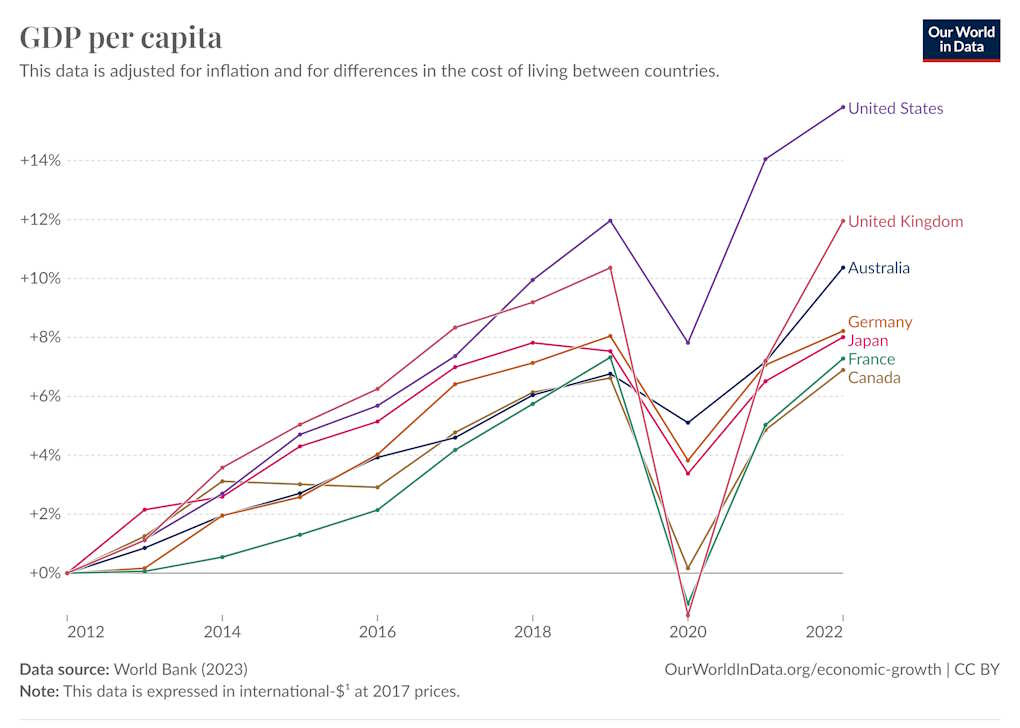

Canada has turned in a disappointing economic performance over the last decade, coming in behind most other rich countries — even slow-growing ones like the UK and Japan:

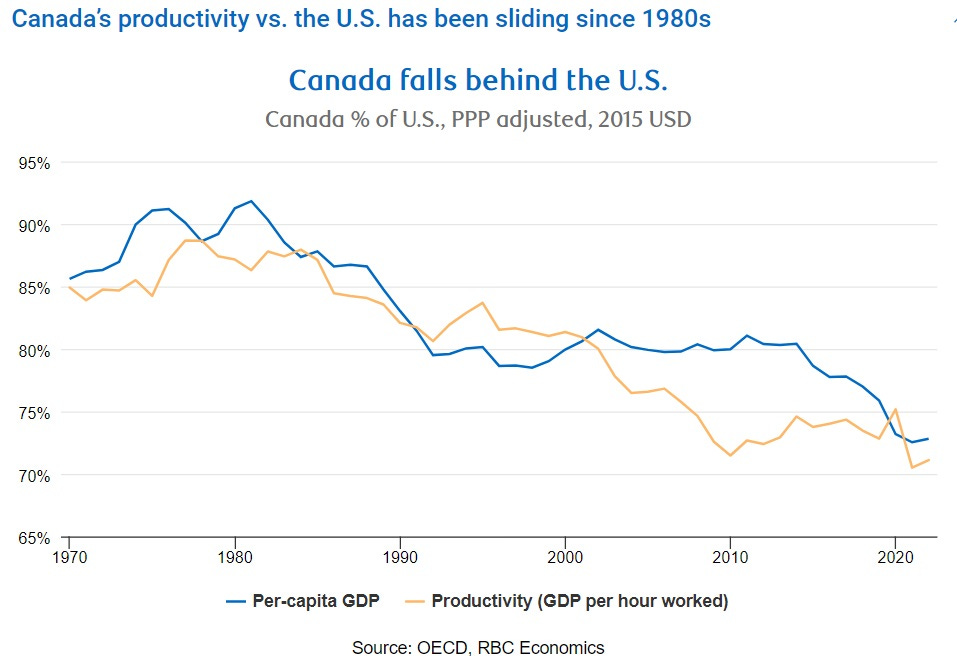

Canada’s productivity levels were close to those of the U.S. in 1980, but have fallen far behind since then:

Source: RBC Economics

This poor performance is a bit of a mystery. Canada is located right next to the fast-growing U.S. It has avoided a financial crisis or other economic calamity. It has arguably the world’s best immigration policy, with a massive continuous influx of high-skilled immigrants. So what’s wrong?

RBC Economics has come out with the first plausible-sounding answer I’ve seen. In a recent article, they argue that Canada’s problem is a combination of low levels of investment and slow productivity growth, caused by regulatory red tape, a lack of R&D, and a pivot from manufacturing and technology to lower-productivity-growth industries like construction and services:

Some of the causes of Canada’s long-term slowdown in economic growth are well-known and clear. Let‘s start with an inefficient regulatory and administrative approval system at all levels of government, which has unintentionally increased internal barriers to trade and growth. Infrastructure chokepoints and red tape further make international trade more difficult than it should be. Those have contributed to lower Canadian business investment, and with that, an overweight of capital going to buildings and construction…As for policy recommendations, there’s some easy libertarian stuff here — slash land-use regulation and red tape at ports, harmonize provincial regulation to enable internal trade, and cut corporate taxes. That’s the low-hanging fruit.

Canadian businesses invest substantially less than in the U.S.—about half as much per worker in aggregate…[P]art of the slowing in investment has been from a pullback in investment in the Canadian oil and gas sector…But, businesses have also invested a substantially smaller share of GDP in the manufacturing sector in Canada than in the U.S. over the last decade…

Businesses have long argued that an inefficient project approvals backdrop is making investing in Canada relatively expensive…

A patchwork of regulatory and administrative rules across different municipalities and provinces is complicated and unintentionally restricts trade within Canada…The International Monetary Fund has estimated that internal trade barriers (for example, regulatory differences across regions, paperwork requirements for businesses in multiple jurisdictions, and certification differences that limit labour mobility) cost the equivalent of a 20% average tariff between provinces…

[T]here remain significant bottlenecks where Canadian infrastructure significantly underperforms. The country’s turnaround times at ports are among the longest in the world…Canada also ranks poorly on “ease of exporting” in global rankings by the World Bank largely due to high document and paperwork costs…

Productivity in Canada lags in most industries versus the U.S., but the Canadian economy is also overweight in construction, where productivity growth has been slower. (...)

But that doesn’t seem like it’ll be enough to do the trick, because the sectoral shift from tech and manufacturing to construction and services will still be a problem. Canada needs to think about dipping its toes into the waters of industrial policy. Exactly what that could look like is a topic for a longer post.

3. If you want good cheap infrastructure, build up state capacity

America has a big problem building infrastructure. Our roads and trains cost much more per mile than other rich countries. There are a number of reasons why this is the case, including land-use regulation, NIMBYism, and broken government contracting processes. But one reason is simply that the U.S. lacks state capacity. We used to have a bunch of highly competent government bureaucrats who knew how to get roads and trains built; then, starting in the 1970s, we fired a bunch of those workers and let much of the in-house expertise decay into nothingness. In its place we hired a bunch of expensive outside consultants whose goal was maximizing their own payouts from the government, rather than providing high-quality infrastructure for the citizenry at a reasonable cost to the taxpayer.

This has been one conclusion of the Transit Costs Project, a panel of experts that has devoted years to studying the problem of rail costs in the U.S. In a recent report on how America could actually build high-speed rail, they reiterate the importance of in-house expertise vs. outside consultants:

With a bank of rail experts in Washington and universities churning out grads with relevant skills, individual projects could reduce their reliance on consultants and do more work in-house. (This was also a recommendation of a previous Transit Costs Project study about local mass transit.) To take a related example, for the price of one consultant contract to study whether to put trash in garbage bins or not, you could hire 10 in-house experts for four years to create a culture of trash expertise at the heart of local government.But this isn’t just speculative. BART, the Bay Area’s commuter rail service, has been replacing its rolling stock (that’s a fancy name for train cars), which it calls the Fleet of the Future project. It has been accomplishing this within a reasonable time frame — not as fast as Japan would, but much faster than we’ve come to expect from California infrastructure projects. And unlike most other California infrastructure projects, Fleet of the Future has come in way under budget!

In a recent update, BART explains the secrets of their success:

BART’s popular Fleet of the Future project has just completed one milestone, with the final car of the original contract now ready for service…In the six years since the first Fleet of the Future train first went into service, the new trains have gone from a surprising sight for riders to an everyday part of their trip….State capacity, folks. It really works. America needs more and better bureaucrats for things like infrastructure, because the alternative is to throw huge amounts of taxpayer money at inefficient outside contractors.

The increased pace in production and delivery of the new fleet has been essential to the transition. Car manufacturer Alstom is now delivering 20 cars a month to BART, almost twice as many as the 11 cars a month stipulated in the original delivery schedule…

The quicker tempo of deliveries is one of the reasons the Fleet of the Future project is expected to come $394 million under budget. Another big cost saver was BART’s decision to have its own highly experienced staff do more of the engineering work in house. The project team, led by John Garnham, has included engineers who have successfully completed new rail car projects at other agencies. (emphasis mine)

4. Why East Asian countries got rich

For well over half a century, economists have been having a wonky but very fascinating debate about how poor countries get rich. The question is how important capital investment is, relative to improvements in technology, education, regulatory policy, industrial structure, trade, urbanization, and other things that get summarized under the name of total factor productivity or multifactor productivity. The answer is important, because the more important capital investment is, the more poor countries can catch up simply by pouring more money into building factories, infrastructure, housing, and offices. Whereas the more important TFP is, the more countries need to focus on making difficult institutional and structural changes in order to keep growing.

Thirty years ago, Paul Krugman wrote an article called “The Myth of Asia’s Miracle”, in which he argued — based on the work of Alwyn Young — that most East Asian countries (with the exception of Japan) had grown fast not because of TFP, but because of high levels of capital investment. Klenow and Rodriguez-Clare (1997) disagreed, arguing that TFP growth stimulates more capital investment, so that we should attribute more of the East Asian growth miracle to TFP than Krugman and Young do. (...)

So basically, China transitioned from TFP-based growth to investment-based growth after the Great Recession. That’s a highly simplified story, but that’s our best guess as to what happened.

The question now is whether China can transition back. The optimistic view — from China’s perspective, anyway — is that the real estate bust will shift resources back to manufacturing, and that Xi Jinping’s massive and unprecedented industrial policy will give a big boost to TFP growth. The pessimistic view is that the shift from TFP-growth growth to investment-based growth in 2008 reflects the inherent limitations of China’s state-driven model, and that it will fall short of countries like Japan and South Korea in terms of living standards. Basically, the question is whether Xi Jinping’s China is more like a newer, bigger South Korea, or more like a newer, bigger Soviet Union.

5. Hanania on race in the 2020s

Richard Hanania is a pundit whose work I generally do not like. His typical analysis relies heavily on racial and gender stereotypes, and he gets a lot of stuff wrong. But ever since a major expose thrust him into the limelight last year, Hanania’s takes have at least, occasionally been more measured and reasonable. And I must give credit where credit is due here, because I think that he had a very good take on the recent “White Women for Kamala” and “White Dudes for Harris” events.

Basically, Hanania argues that after a decade of singling White people out for collective castigation, the progressive movement is accepting White people as just another racial interest group worthy of inclusion in the coalition:

One thing right-wingers love is to complain that you can only have affinity groups for blacks and other minorities…Along comes the Kamala campaign and says it’s ok to be white. That is, as long as you’re a good person, which means supporting reproductive freedom, not being “weird,” and voting Democrat. We’re all in this together.This sounds basically right to me. White people are not yet a numerical minority in America — and depending on how many Hispanic and multiracial Americans define themselves as White, they may never be. But events like “White women for Kamala” show that the progressive movement may simply decide to treat White progressives as just one more minority identity group in a rainbow coalition.

It seems “woke” on the surface, but it’s actually a sign that liberals are moving away from woke. In 2020, something like this wouldn’t have even been possible. Talk of “whites” in left-coded spaces only occurred in the context of flogging them for their sins. In 2024, you can be a white dude for Kamala and it’s totally cool. The symbol for “White Dudes for Harris” is a trucker hat, showing self-deprecating humor and membership in a movement that is not at all weird or neurotic about race.

White people receive the message that Democrats do not consider you the problem. You’re welcome into the coalition. There’s even a Zoom call you can join, and don’t worry, it won’t be just Robin DiAngelo telling you how much you suck. Kamala has made clear that she’s *only* considering white men for VP…

Republicans have been caught flat-footed. Conservatives want to portray these events as a kind of 2020 DEI struggle session, and they can find clips backing up that view, but people who have attended say that there was actually very little of that…

What else can conservatives say in response? I’ve seen a little bit of “why can’t we have a whites for Trump thing?” Well, who’s stopping you? It’s a free country. Organize “whites for Trump” and see what happens…There will be no “Whites for Trump” event because the campaign would never allow it, understanding it would be a PR nightmare. “Whites for Trump” would draw sewer dwellers, instead of the nice, seemingly normal people that came out for Harris…

We can now all see the hopelessness and stupidity of white nationalism, which wants to argue that the 220 million American whites who are at each other’s throats over social issues and values should unite under one umbrella because they share the same interests. The only way white identitarianism would have had any hope is if liberalism stayed in summer of Floyd mode indefinitely, where you push anti-white rhetoric so blatantly and aggressively that it causes a natural reaction.

Whites for Kamala completely defuses any hope of building a broad white identitarian coalition.

And I think Hanania is also right that if this happens, it will take a lot of the wind out of the sails of white nationalism and rightism in general. For most people, being part of a minority group in a rainbow coalition probably sounds like a better deal than fighting a grim race war to try to expel other groups en masse or break up the nation just to be a supermajority again.

But at the same time, I think there’s another vision that’s even better than the rainbow coalition. If national identity can be strengthened, and the salience of racial identities weakened, Americans wouldn’t have to define their place in American society by the circumstances of their birth. The proper counter to progressive identitarianism will never be White nationalism; it will always be American nationalism.

Update: I also like Hanania’s take on progressives re-embracing patriotism and the American flag. I don’t think it’s quite true yet, but I think it’s what should happen, and maybe by the end of this decade it will.

6. San Francisco nonprofits are both corrupt and ineffectual

In 2022, there was a big tech bust that deprived the city of San Francisco, and the state of California in general, of a lot of tax revenue. At that point, San Francisco began taking a harder look at the nonprofits to which it has famously outsourced many of its social services. Unsurprisingly, many cases of incompetence and outright corruption are being discovered. (...)

by Noah Smith, Noahpinion | Read more:

Images: Bloomberg; Slejven Djurakovic on Unsplash

.jpg)