In eras of stability when little changes, the capacity to adapt takes a back seat. As noted in

Why Political "Solutions" Don't Fix Crises, They Make Them Worse, absent any pressure from tumultuous change, nature is hard-wired to keep the genetic instructions unchanged, as there is little selective benefit in modifying what's working well and potential risks in messing with it.

In other words, nature is conservative in eras of stability and low volatility. Since its genetic instructions are working pretty well, the shark genome is relatively stable over millions of years, with a few tweaks here and there to adapt to changes in its environment.

But adaptative churn takes the driver's seat when the ecosystem changes rapidly and the existing instructions are failing. This is the

adapt or die moment, when species must experiment by churning out modifications (semi-random mutations in the instructions) and test them in trial-and-error: the ones that add selective advantages live, the ones that don't die.

If this period of intense adaptive experimentation is ultimately successful, the species' rate of change spikes and then drifts down to the baseline of low activity. This is known as

punctuated equilibrium: the instructions drift along when nothing much is changing, suddenly spike when selective pressures shoot up, threatening extinction, and then diminish as the new adaptations relieve the selective pressure.

All this is automatic and beyond the individual's and the species' conscious control. We can't order our genome to speed up mutations and get cracking on the adaptive modifications.

Human civilization operates on the same principles of

adapt or die: when circumstance change, selective pressures mount and the society must adapt or perish.

What's different is humans can stifle or encourage adaptive churn. As social beings hard-wired to organize ourselves in hierarchies, those at the top of the power pyramid will naturally deploy all their power to conserve the status quo, as any modifications might threaten their outsized share of

all the good things such as wealth and status.

The view from the top of the pyramid is rather grand. Those at the top see the vastness of the imperial reach, the army's strength, the peasantry toiling away and the obsequious Mandarin bureaucrats bowing and scraping, and the idea that all this immense structure could decay and blow away is incomprehensible.

There is little sense in the top circle that the extinction of the entire social order is a threat. The threat is more personal: is my private fiefdom at risk of being diminished? Are rivals gaining influence? Are the reforms being proposed positive for my fortunes or could they pose a threat?

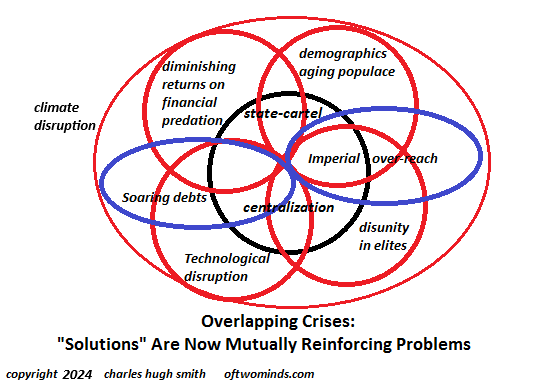

This narrow view of the overlapping crises (a.k.a.

polycrisis) favors short-term expediency over more radical long-term modifications, as the

Powers That Be have a grip on expedient "stave off the immediate crisis" measures such as imposing curfews, lowering interest rates and increasing the pay of soldiers, but these measures are slapdash rather than part of a recognition that radical changes in the structure of the society must be organized now, not later, for later will be too late.

In other words, there is no urgency for the kind of reforms needed to avoid extinction, there is only urgency for expedient "kick the can down the road" measures because these measures 1) are within easy reach and 2) they don't threaten the pyramid of power the "deciders" dominate.

Put another way, faced with skyrocketing risks of a heart attack, the leadership concludes that cutting out the HoHos but keeping the DingDongs and Twinkies will be enough to maintain the status quo. That the crises demand a complete overhaul of diet and fitness, now, not later, is both 1) too painful to contemplate, and 2) beyond the reach or the leadership's atrophied adaptive skillset: the leadership only has experience with managing stability, not tumultuous crises.

There is an irony in this atrophy of competence: the longer

the good times roll, the less experience anyone has of polycrisis. In the competitive churn at the top of the pyramid, the skills that are most valuable in periods of stability are those of bureaucratic in-fighting and maintaining the status quo. Since there is no selective pressure demanding radical changes to survive, the skills needed to manage such a radical transition are nor longer present.

Those with the necessary character and skills to manage radical transformations have all been sent to Siberia for threatening the status quo with all their crazy proposals. Those in power have been selected to believe the organization they rule is perfectly capable of adjusting as needed, without actually changing anything. (...)

So quality decays first, then quantity decays, too. Each crisis reveals another layer of

under-competence and dry-rotted foundations, and each one is dutifully papered over.

Those few who grasp the crisis in its entirety have been marginalized, and those who are left are drifting downstream, unable to move the mass of self-interested inertia even if they wanted to--and they don't really want to because why should we risk upsetting such a splendid arrangement that's capable of handling anything that arises with ease?

Decay is a perfectly adequate strategy if there's sufficient resources to keep everything glued together as it slowly unravels. Magical thinking (AI!) helps smooth the decline, and soon everyone habituates to decay.

Polycrisis has a way of disrupting decay. If conditions remain stable, decay can be managed. But if volatility soars and multiple crises arise and reinforce each other, decay accelerates into collapse.

[ed. Pretty straightforward. But, what 'radical' actions should be pursued (and how)?]