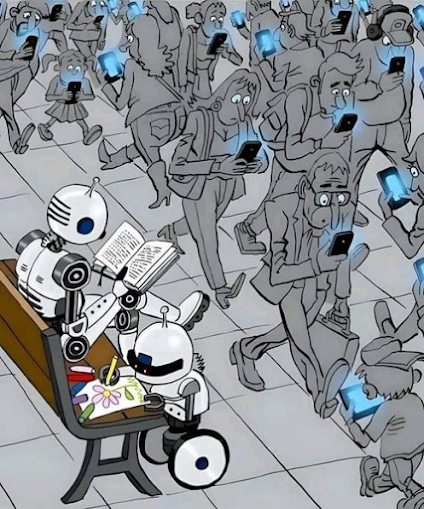

This book is about that line and the challenges that this century will bring to it. I hope to convince you of three things. First, our culture, morality, and law will have to face new challenges to what it means to be human, or to be a legal person— and those two categories are not the same. A variety of synthetic entities ranging from artificial intelligences to genetically engineered human- animal hybrids or chimeras are going to force us to confront what our criteria for humanity and also for legal personhood are and should be.

Second, we have not thought adequately about the issue, either individually or as a culture. As you sit there right now, can you explain to me which has the better claim to humanity or personhood: a thoughtful, brilliant, apparently self- aware computer or a chimp- human hybrid with a large amount of human DNA? Are you even sure of your own views, let alone what society will decide?

Third, the debate will not play out in the way that you expect. We already have “artificial persons” with legal rights— they are called corporations. You probably have a view on whether that is a good thing. Is it relevant here? And what about those who claim that life begins at conception? Will the pro- life movement embrace or reject an Artificial Intelligence or a genetic hybrid? Will your religious beliefs be a better predictor of your opinions, or will the amount of science fiction you have watched or read?

For all of our alarms, excursions, and moral panics about artificial intelligence and genetic engineering, we have devoted surprisingly little time to thinking about the possible personhood of the new entities this century will bring us. We agonize about the effect of artificial intelligence on employment, or the threat that our creations will destroy us. But what about their potential claims to be inside the line, to be “us,” not machines or animals but, if not humans, then at least persons, deserving all the moral and legal respect that any other person has by virtue of their status? Our prior history in failing to recognize the humanity and legal personhood of members of our own species does not exactly fill one with optimism about our ability to answer the question well off- the- cuff.

In the 1780s, the British Society for the Abolition of Slavery had as its seal a picture of a kneeling slave in chains, surrounded by the words “Am I not a man and a brother?” Its message was simple and powerful. Here I am, a person, and yet you treat me as a thing, as property, as an animal, as something to be bought, sold, and bent to your will. What do we say when the genetic hybrid or the computer- based intelligence asks us the very same question? Am I not a man— legally, a person— and a brother? And yet what if this burst of sympathy takes us in exactly the wrong direction, leading us to anthropomorphize a clever chatbot, or think a genetically engineered mouse is human because it has large amounts of human DNA? What if we empathetically enfranchise Artificial Intelligences who proceed to destroy our species? Imagine a malicious, superintelligent computer network, Skynet, interfering in, or running, our elections. It would make us deeply nostalgic for the era when all we had to worry about was Russian hackers.

The questions run deeper. Are we wrong even to discuss the subject, let alone to make comparisons to prior examples of denying legal personality to humans? Some believe that the invocation of “robot rights” is, at best, a distraction from real issues of injustice, mere “First World philosophical musings, too disengaged from actual affairs of humans in the real world.” Others go further, arguing that only human interests are important and even provocatively claiming that we should treat AI and robots as our “slaves.” In this view, extending legal and moral personality to AI should be judged solely on the effects it would have on the human species, and the costs outweigh the benefits.

If you find yourself nodding along sagely, remember that there are clever moral philosophers lurking in the bushes who would tell you to replace “Artificial Intelligence” with “slaves,” the phrase “human species” with “white race,” and think about what it took to pass the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution. During those debates there were actually people who argued that the idea of extending legal and moral personality to slaves should be judged solely on the effects it would have on the white race and the costs outweighed the benefits. “What’s in it for us?” is not always a compelling ethical position. (Ayn Rand might have disagreed. I find myself unmoved by that fact.) From this point of view, moral arguments about personality and consciousness cannot be neatly confined by the species line; indeed they are a logical extension of the movements defending both the personality and the rights of marginalized humans. Sohail Inayatullah describes the ridicule he faced from Pakistani colleagues after he raised the possibility of “robot rights” and quotes the legal scholar Christopher Stone, author of the famous environmental work Should Trees Have Standing?, in his defense: “[T]hroughout legal history, each successive extension of rights to some new entity has been theretofore, a bit unthinkable. We are inclined to suppose the rightlessness of rightless ‘things’ to be a decree of Nature, not a legal convention acting in support of the status quo.”

As the debate unfolds, people are going to make analogies and comparisons to prior struggles for justice and, because analogies are analogies, some are going to see those analogies as astoundingly disrespectful and demeaning. “How dare you invoke noble X in support of your trivial moral claim!” Others will see the current moment as the next step on the march that noble X personified. I feel confident predicting this will happen— because it has. The struggle with our moral future will also be a struggle about the correct meaning to draw from our moral past. It already is.

In this book, I will lay out two broad ways in which the personhood question is likely to be presented. Crudely speaking, you could describe them as empathy and efficiency, or moral reasoning and administrative convenience.

The first side of the debate will revolve around the dialectic between our empathy and our moral reasoning. As our experiences of interaction with smarter machines or transgenic species prompt us to wonder about the line, we will question our moral assessments. We will consult our syllogisms about the definition of “humanity” and the qualifications for personhood— be they based on simple species- membership or on the cognitive capacities that are said to set humans apart, morally speaking. You will listen to the quirky, sometimes melancholy, sometimes funny responses from the LaMDA- derived emotional support bot that keeps your grandmother company, or you will look at the genetic makeup of some newly engineered human- animal chimera and begin to wonder: “Is this conscious? Is it human? Should it be recognized as a person? Am I acting rightly toward it?”

The second side of the debate will have a very different character. Here the analogy is to corporate personhood. We did not give corporations legal personhood and constitutional rights because we saw the essential humanity, the moral potential, behind their web of contracts. We did it because corporate personality was useful. It was a way of aligning legal rights and economic activity. We wanted corporations to be able to make contracts, to get and give loans, to sue and be sued. Personality was a useful legal fiction, a social construct the contours of which, even now, we heatedly debate. Will the same be true for Artificial Intelligence? Will we recognize its personality so we have an entity to sue when the self- driving car goes off the road or a robotic Jeeves to make our contracts and pay our bills? And is that approach also possible with the transgenic species, engineered to serve? Or will the debate focus instead on what makes us human and whether we can recognize those concepts beyond the species line and thus force us to redefine legal personhood? The answer, surely, is both.

The book will sometimes deal with moral theory and constitutional or human rights. But this is not the clean- room vision of history in which all debates begin from first principles, and it is directed beyond an academic audience. I want to understand how we will discuss these issues as well as how we should. We do not start from a blank canvas, but in medias res. Our books and movies, from Erewhon to Blade Runner, our political fights, our histories of emancipation and resistance, our evolving technologies, our views on everything from animal rights to corporate PACs, all of these are grist to my mill. The best way to explain what I mean is to show you. Here are the stories of two imaginary entities. Today, they are fictional. Tomorrow? That is the point of the book.

by James Boyle, The Line (full book) | Read more:

Image: The Line

[ed. This was also a central theme in Issac Asimov's I Robot series with the robot R. Daneel Olivaw, who was almost indistinguishable from humans. See also: James Boyle's new book The Line explores how AI is challenging our concepts of personhood (Duke Law):]

"A longtime proponent of open access, Boyle, the William Neal Reynolds Distinguished Professor of Law, is a founding board member of Creative Commons, an organization launched in 2001 to encourage the free availability of art, scholarship, and cultural materials through licenses that individuals and institutions can attach to their work. Boyle has made The Line accessible to all as a free download under such a license. It is also available in hardcover or digital formats.

In The Line, Boyle explores how technological developments in artificial intelligence challenge our concept of personhood, and of "the line" we believe separates our species from the rest of the world – and that also separates "persons" with legal rights from objects – and discusses the possibility of legal and moral personhood for artificially created entities, and what it might mean for humanity’s concept of itself."