Thursday, June 12, 2025

Deport Dishwashers or Solve Murders?

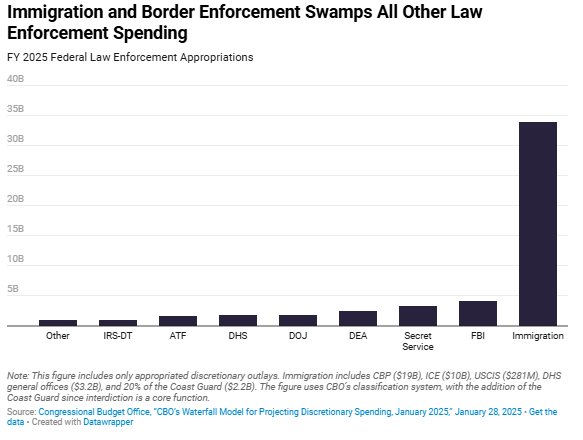

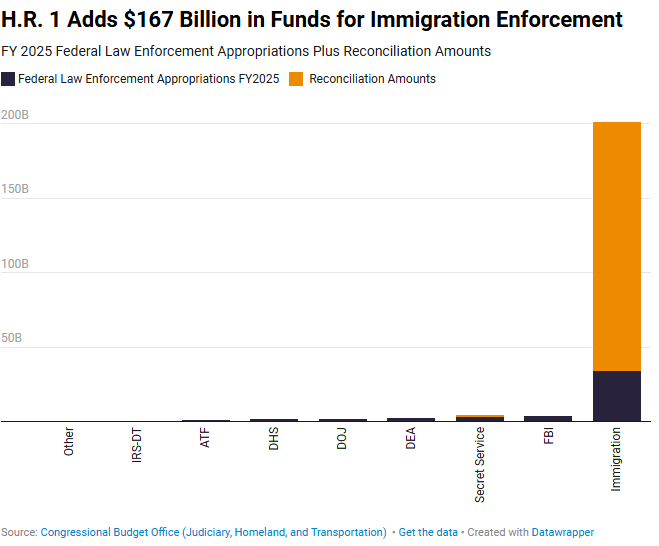

Yet that’s exactly how the federal government allocates resources. The federal government spends far more on immigration enforcement than on preventing violent crime, terrorism, tax fraud or indeed all of these combined.

Moreover, if the BBB bill is passed the ratio will become even more extreme. (sere also here):

Don’t make the mistake of thinking that immigration enforcement is about going after murderers, rapists and robbers. It isn’t. Indeed, it’s the opposite. ICE’s “Operation At Large” for example has moved thousands of law enforcement personnel at Homeland Security, the FBI, DEA, and the U.S. Marshals away from investigating violent crime and towards immigration enforcement.

I’m not arguing against border enforcement or deporting illegal immigrants but rational people understand tradeoffs. Do we really want to spend billions to deport dishwashers from Oaxaca while rapes in Ohio committed by US citizens go under-investigated?

Almost half of the murders in the United States go unsolved (42.5% in 2023).

The greatest obstacle to sound economic policy is not entrenched special interests or rampant lobbying, but the popular misconceptions, irrational beliefs, and personal biases held by ordinary voters. This is economist Bryan Caplan's sobering assessment in this provocative and eye-opening book. Caplan argues that voters continually elect politicians who either share their biases or else pretend to, resulting in bad policies winning again and again by popular demand.

Boldly calling into question our most basic assumptions about American politics, Caplan contends that democracy fails precisely because it does what voters want. Through an analysis of Americans' voting behavior and opinions on a range of economic issues, he makes the convincing case that noneconomists suffer from four prevailing biases: they underestimate the wisdom of the market mechanism, distrust foreigners, undervalue the benefits of conserving labor, and pessimistically believe the economy is going from bad to worse. Caplan lays out several bold ways to make democratic government work better--for example, urging economic educators to focus on correcting popular misconceptions and recommending that democracies do less and let markets take up the slack.

The Myth of the Rational Voter takes an unflinching look at how people who vote under the influence of false beliefs ultimately end up with government that delivers lousy results.

"Elon has left the Trump White House to pursue the full-time venture of Twitter canceling his former boss. Silicon Valley and MAGA conservatism were always an odd fit—tied more by who they hated than what they support.

I’m still fascinated and befuddled by what drove so many founders and investors to support Trump in 2024. Most of these folks are not deep Republican partisans or racist caricatures; many are even intelligent, well-intentioned, and politically engaged—yet voted in a way I consider deeply and destructively wrong.

I trawled my group chats for someone willing to have a candid conversation. This person is a founder, immigrant, and Bernie-to-Trump supporter. Below, we discuss “country club Democrats,” why founders see themselves in Trump, and why he turned on the current administration.

Tell me about your background.

I’m a startup founder. I’m originally from Chile, and grew up across Chile, the US, and France.

How would you describe your political orientation?

Heterodox is one way to put it.

My parents are the children of wealthy, left-leaning intellectuals. I discovered Marxism around 14, and that really opened my eyes. The idea of human dignity really mattered to me. When you read stories of the US factories and the meat producers, it’s fucking nuts.

Bernie announced his candidacy in 2015, when I was finishing high school in the US. He was the first politician who really touched me. I would cry at Bernie speeches. His theory of economics felt so true, about a class being left behind. The 2016 election was very unexciting at first because the polls were all Jeb Bush vs. Hillary Clinton. It felt so trite and boring. Then Bernie announced, and I became a complete aficionado. I had a Bernie Instagram account. It was his authenticity.

My disillusionment with establishment Democrats started during that primary, because it felt rigged. You could see television actively lying about who Bernie was, using sound bites incorrectly, picking favorites. I never felt Hillary Clinton was elected. She was just appointed.

Anyway, Bernie loses. Trump is in the race at that point, and you get to the actual election. At that point, I'm basically a Trump supporter. I always think of politics as having a candidate of hope and a candidate of the status quo. I felt that Trump was the candidate of hope, weirdly enough.

No. It was like, fuck these people that stole the election from Bernie. They're not on our side. If you look at where Bernie versus Hillary stood in 2016, she was essentially a Republican in ways that were the worst of both worlds. She had the elitism of Democrats, and also all the bad neoliberal policies that Bernie fought against. The pitch was literally, "My name is Hillary Clinton." And it's like, "Says who?" Trump winning was the revenge of the Internet, in some ways.

Trump 1.0 was very much about immigration. You're an immigrant from Latin America. Was that weird?

No. I wasn't in the US for most of Trump 1.0, so it never came my way. I knew he delayed visas. I never took it as a big deal. My perception of Trump 1.0 was that the first year was really tumultuous, and the other three years were actually really good. (...)

Trump has this unpredictability, the willingness to do shit that maybe you shouldn't do. That worked with his foreign policy. He knows how to empire.

U.S. Open 2025: Feel the Pain

With Ate by his side come hot from hell,

Shall in these confines with a monarch’s voice

Cry “Havoc!” and let slip the dogs of war,

That this foul deed shall smell above the earth

With carrion men, groaning for burial.

—USGA Internal Document (Top Secret)

OAKMONT, Pa. — On Tuesday, walking back to the clubhouse from the far reaches of Oakmont Country Club, I saw a group of maybe a dozen men spread across the right rough on the first hole, using leaf blowers on the grass.

"Look at that," I said, "they don't want a single leaf showing."

"It's not that," said my co-worker, reminding me that there are virtually no trees anymore inside the property. "They're doing it to puff up the rough, so it catches the ball and makes everything harder."

For one week a year, we are allowed as golf fans to become untethered from the tender mercies, and root for carnage and hell. For one week, we are free to indulge our inner NASCAR fan and root for a crash. For one week, we can, judo-like, reverse the sadism that golf has delivered into our lives and project it onto the elites. No longer will the pampered sons of athletic privilege shoot 35 under on some pristine plot of soulless turf. Now, they must pay with their sweat and tears, and, ideally, blood, while we whistle and jeer from the sidelines.

That week is the U.S. Open.

Somewhere along the way, though, the U.S. Open lost its way. Four of the last five years, the winning score has been six under (the other time, it was 10 under). In the last 11 years, only one player has hoisted the championship trophy without breaking par for 72 holes. Long gone are the days when grown men would moan that they had "lost the course," or rake putts in a fit pique. There is a softness about this championship now and—at the risk of sounding melodramatic—it breaks the heart of America.

Oakmont, mighty Oakmont, presents a chance for what scholars of war call revanchism—the re-conquering of lost lands. This is a place known for its rigor, right back to the days of its founder, Henry Fownes. This self-made steel baron was something of a minor lunatic, and he constructed the course in response to the softness he saw around him. Great triumph should only be achieved through merciless struggle, he believed, and thus did his lunatic things like forming actual furrows into the bunker with 100-pound rakes. His son, W.C. Fownes, who was largely responsible for launching Oakmont onto the national stage, was a much better golfer than his father and possibly an even bigger lunatic. Here's a quote from the younger Fownes, in response to those who moaned about the difficulty of his course, that is somehow not fictional:

"Let the clumsy, the spineless, the alibi artist stand aside! A shot poorly played should be a shot irrevocably lost!"

Where, today, are men such as these? Where have all the cowboys gone?

Point is, a certain level of sadism is baked into the bloodline of Oakmont, and there is no better place for the U.S. Open to rediscover its spirit. Where better to find that old, indomitable steel than the steel city itself?

It will not be easy. The clumsy, the spineless and the alibi artists will clamor for mercy, and they'll use every craven tool at their disposal. Complaints from players, agents and certain elements of the quisling media will heap pressure on the men and women of courage who run the show, and they will seek a terrible outcome: Slow the greens, trim the rough, and encourage the dreaded birdie.

What's wrong, they'll ask, with six under par?

At the U.S. Open, everything! Everything is wrong with it!

In fact, those us who root for the pros to endure a bitter, disheartening experience these four days are in it just for the schadenfreude—although it is mostly that. We're also looking out for them. Anyone can win a wedge-and-putt contest, but only a grim warrior, a mud-speckled soldier of the earth itself, and emerge from the meat grinder of a truly destructive U.S. Open. By encouraging butchery, we give each of them the chance to win a glory unmatched. Pain is a gift!

[ed. Let the carnage begin. See also: U.S. Open 2025: It's not all doom and gloom at Oakmont, depending on who you ask (GD).]

Wednesday, June 11, 2025

U.S. Bottled Water Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report

The U.S. bottled water market size was estimated at USD 47.42 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow at a CAGR of 5.7% from 2025 to 2030. This can be attributed to increasing health and wellness trends among consumers, the rising need for convenience and accessibility, and robust production innovation. The growing demand and consumption of bottled water can largely be attributed to increasing health consciousness among consumers. With rising awareness about the harmful effects of sugary beverages, such as sodas and juices, people are shifting towards healthier hydration options.

Convenience also plays a crucial role in the rising demand for bottled water. It offers unmatched portability, making it easy for consumers to stay hydrated while on the go. Bottled water is readily available in grocery stores, convenience shops, and vending machines, which enhances its appeal as a staple beverage choice. This accessibility has solidified bottled water's position as one of the most popular beverage categories in the country.

Marketing strategies have further contributed to the growth of the bottled water industry. Companies have successfully created strong brand loyalty through campaigns that emphasize the purity and safety of bottled water compared to tap water. In some regions, concerns about tap water quality have bolstered consumer preference for bottled options, positioning them as a reliable source of hydration. Innovations in product offerings have also played a significant role in market expansion. The emergence of functional bottled waters-enhanced with vitamins, minerals, or flavor infusions-has attracted health-oriented consumers looking for added benefits beyond basic hydration. This segment is expected to grow substantially in the coming years, driven by consumer demand for beverages that provide health advantages. In addition, advancements in eco-friendly packaging are addressing environmental concerns while appealing to sustainability-minded consumers.

A notable factor propelling the growth of the bottled water industry is robust production innovation. This involves the introduction of enhanced manufacturing processes and the development of new product variants to meet diverse consumer demands and preferences. Innovations in packaging, such as eco-friendly materials and convenient designs, along with advancements in water purification and flavor infusion technologies, have significantly contributed to making bottled water more attractive to consumers. These innovative efforts not only aim to improve product quality and sustainability but also seek to differentiate offerings in a highly competitive market, thus driving consumer interest and market growth. (...)

Product Insights

Purified water accounted for a revenue share of 40.4% in 2024 in the U.S. market. Purified bottled water offers a convenient, portable hydration option, especially for people on the go, making it easy to access clean water anytime and anywhere. The increasing focus on personal health and wellness has led to a growing preference for purified water, which is perceived as a cleaner, more beneficial option compared to tap or other types of bottled water. Health-conscious consumers view purified water as free of impurities like chemicals, heavy metals, and bacteria, aligning with their desire for healthier hydration choices. (...)

Packaging Insights

PET bottled water accounted for a revenue share of 80.1% in 2024, owing to its significant advantages in convenience, recyclability, and lightweight nature compared to other packaging materials. The widespread preference for PET bottles among consumers stems from their ease of transport and use, alongside a growing awareness and concern for environmental sustainability. PET bottles, being fully recyclable, align with increasing global initiatives towards reducing plastic waste and promoting circular economies. Furthermore, the lightweight characteristics of PET bottles reduce transportation costs and carbon footprint, making them a favored choice among manufacturers and consumers alike, thus driving their market growth. [ed. ...and disposal]

In October 2023, Coca-Cola India launched its first 100% recycled polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottle, specifically for its Kinley packaged drinking water brand. This initiative marks a significant step towards promoting sustainability and plastic circularity in the country. The company introduced these bottles as part of its broader commitment to environmental responsibility and aims to reduce its carbon footprint.

The canned bottled water segment is expected to grow at a CAGR of 7.0% from 2025 to 2030. This can be primarily attributed to increasing consumer awareness towards environmental sustainability. It can offer an eco-friendlier alternative to plastic bottles due to their higher recyclability rate and efficiency in transportation, which contributes to lower carbon emissions. In addition, the convenience and durability of cans appeal to active and on-the-go lifestyles, making them a popular choice among consumers. As a result, both beverage companies and consumers are shifting towards canned water, driving significant growth in this market segment. For instance, in April 2024, Coca-Cola’s Smartwater brand unveiled 12-ounce aluminum cans with a new design, marking the first instance of vapor-distilled water being offered in this packaging format. The cans feature both Smartwater Original and SmartWater Alkaline with Antioxidant, catering to consumer preferences for convenient and environmentally friendly options. (...)

Key U.S. Bottled Water Companies:

- Adidas AG

- Nestlé

- PepsiCo

- The Coca-Cola Company

- DANONE

- Primo Water Corporation

- FIJI Water Company LLC

- Gerolsteiner Brunnen GmbH & Co. KG

- VOSS WATER

- Nongfu Spring

- National Beverage Corp.

- Keurig Dr Pepper Inc.

- Recent Developments

Tuesday, June 10, 2025

Frank Zappa & the Mothers of Invention

After more than 50 years in limbo, Frank Zappa’s long-shelved 1974 TV special Cheaper Than Cheep—originally shot guerrilla-style inside his Sunset Boulevard rehearsal space—is finally getting its due. Conceived as a DIY clapback to the commercially slick, glossy music shows of the era, the footage was benched thanks to clunky mid-’70s A/V sync issues. (...)

The set captures Zappa and his 1974 band in terrific form, blurring the line between rehearsal and performance, and making a bulletproof case for why this lineup is held in such high regard. It’s loose, it’s tight, it’s weird, it’s Zappa. The impeccable musicianship and occasional onstage chaos sounds GREAT. via

The Reality of Fan Disillusionment

However, Fanatic (성덕), Oh Se-yeon’s 2021 documentary, seemed different from the get-go: it’s about the fans left behind when their fan objects have had a (deserved) fall from grace.

This is a deeply personal documentary on Oh’s part. She participates on-screen and discloses her struggle with the dissonance that comes with being confronted with an uncomfortable truth. In her case, she spent 7 years as a fan of singer Jung Joon-young, who was convicted of aggravated rape in 2019. Evidence of these crimes were uncovered in relation to the Burning Sun scandal that rocked South Korea.

Mr. Jung, along with other members of an online chat group, had bragged about drugging and raping women and had shared surreptitiously recorded videos of assaults.This wasn’t the first time Jung was in hot water, having been the subject of allegations in 2016, which fans defended him from. But the evidence made the allegations a reality. What’s a fan to do when the illusion of their idol’s good nature is shattered so definitively? This isn’t about dating the wrong person, having a drug scandal, speaking out of turn, or delivering a subpar product, these actions are recognized as criminal for a reason.

The documentary doesn’t try to make fun of or pathologize fans; Oh wants to understand the emotional response that she and her fellow fans experienced. In an interview with Korea JoongAng Daily, she explains,

“When you become a fanatic, when you love someone to that extent, you don’t realize that you're doing that, that you’re the giving tree. I wanted to give everything to him, but I didn’t feel like I was sacrificing or giving up too much. That’s how immersed, devoted I was.”Oh’s comment that “you don’t realize that you’re doing that” stands out as part of the problem. You don’t realize how deep you’re in until something happens that challenges your reality. It’s why I find it difficult to address comments about how stans are happy to be shelling out thousands and dedicating their lives to their fan object. Many things that we engage in willingly and that feel good in the moment are not necessarily good for us. Euphoric highs and dopamine hits don’t translate to healthy dynamics, in fact, they usually come at a cost.

In a way, the film explores whether it’s possible to go back to being normal after this type of crisis. It’s one thing to grow out of your interest, have it displaced by real life activities and attachments, it’s another matter entirely to be faced with a conflict so profound that it shakes you to the core.

Oh speaks to friends of hers who have experienced similar fractures with other artists. Even her mother is featured as someone whose favourite actor was disgraced in a #MeToo scandal. Her quest to understand the driving force behind supporters that remain loyal lead her to a political rally in support of former South Korean president, Park Geun-hye, who was sentenced to 20 years in prison in 2018.

The discussions with fellow fans who were trying to make sense of their emotional reactions really resonated with me. The so-called “waking up” to just how deeply invested they were in what turned out to be an illusion. Because when there’s a perceived moral duty to defend your fan object, you’re operating on deeply felt knowledge that it’s what’s right. But that type of knowledge and belief can mislead us. Where do we go when the veracity of this knowledge, the basis for this unshakeable faith, is completely destroyed?

The evergreen response to fans feeling betrayed is that their fan objects don’t owe them anything. But this isn’t about the fans being owed something, it’s about emotional responses that cannot be reasoned away.

“Are we victims or perpetrators?”

There is also the question of what fans’ role is in all of this. Many fans feel a degree of responsibility for what happened, even as they themselves feel victimized. If you find it ridiculous that fans feel betrayed by someone they don’t know, the fact that so many of them feel that they need to answer for the crimes of their fan object should reveal the degree of attachment we’re discussing.

So much of it is about feelings. We can know, logically, that we aren’t responsible for someone else’s actions, but the guilt can still gnaw at you with tremendous force. Would these fan objects have become criminals even without being in the public eye? One fan feels like she helped commit the crimes. Another wonders if the adulation fundamentally changed who the idol was for the worse. Oh says in the film, “It seems like the support and love I gave that person became the driving force behind the crime and deception.” (...)

But some fans still remain. Excuses are made, even in a case like Jung’s. He was an innocent bystander and was tricked, or took the fall for a friend that was the primary perpetrator. It may seem extreme, but the mechanism behind these copes is the same across the board. Whether you want to call it betrayal blindness, cognitive dissonance resolution, or plain old denial, it’s operates the same whether a fan object is being defended from accusations of greed or an outright crime.

The moral violations may be trivial, but the response to them can nonetheless be outsized. Whether it’s right or justified is irrelevant in the face of the emotional tsunamis that materialize.

These experiences are universal, and a result of our parasocial investments. Seemingly an obvious statement, yet I feel like it’s rarely acknowledged. Or rather, parasocial attachment is treated like something that only happens to weirdos, but it’s something we all engage in. The most extreme form is something I’ve come to call parasocial limerence, which denotes a more intense, obsessive form. This term may be needed to differentiate between degrees and types of parasocial attachments.

It didn't click. The students had been following along up to that point and comprehended the basic idea of how watching exerts a form of control over the watched, but the whole thing broke down when they were asked to apply the same logic to a pop star. It was fascinating to see."

Monday, June 9, 2025

I Analyzed the Chord Progressions of 680,000 Songs

“Chordonomicon” was coined by 5 researches last October when they needed a name for a new project that they’d just completed. This project pulled together chord progressions and genres for nearly 680,000 songs from the popular music learning website Ultimate-Guitar. I knew I had to do something with the data. But what? (...)

I didn’t really have a hypothesis to test with the Chordonomicon dataset, though. I just wanted to explore what was in there. There had to be something interesting among 680,000 chord progressions. And there was. But, first, we should start with a simple question: What’s a chord?

If you’re looking for in depth discussions on music theory, I’m not your guy. (You should probably turn to someone like Ethan Hein and his newsletter Ethan teaches you music.) But for this case, I think some basic definitions will help. A “note” is a single pitch. When you hit one key on the piano, for example, you are playing a note. An “interval” is a combination of two notes. A “chord” is a combination of three or more unique notes (e.g., a C major chord is comprised of the notes C, E, and G).

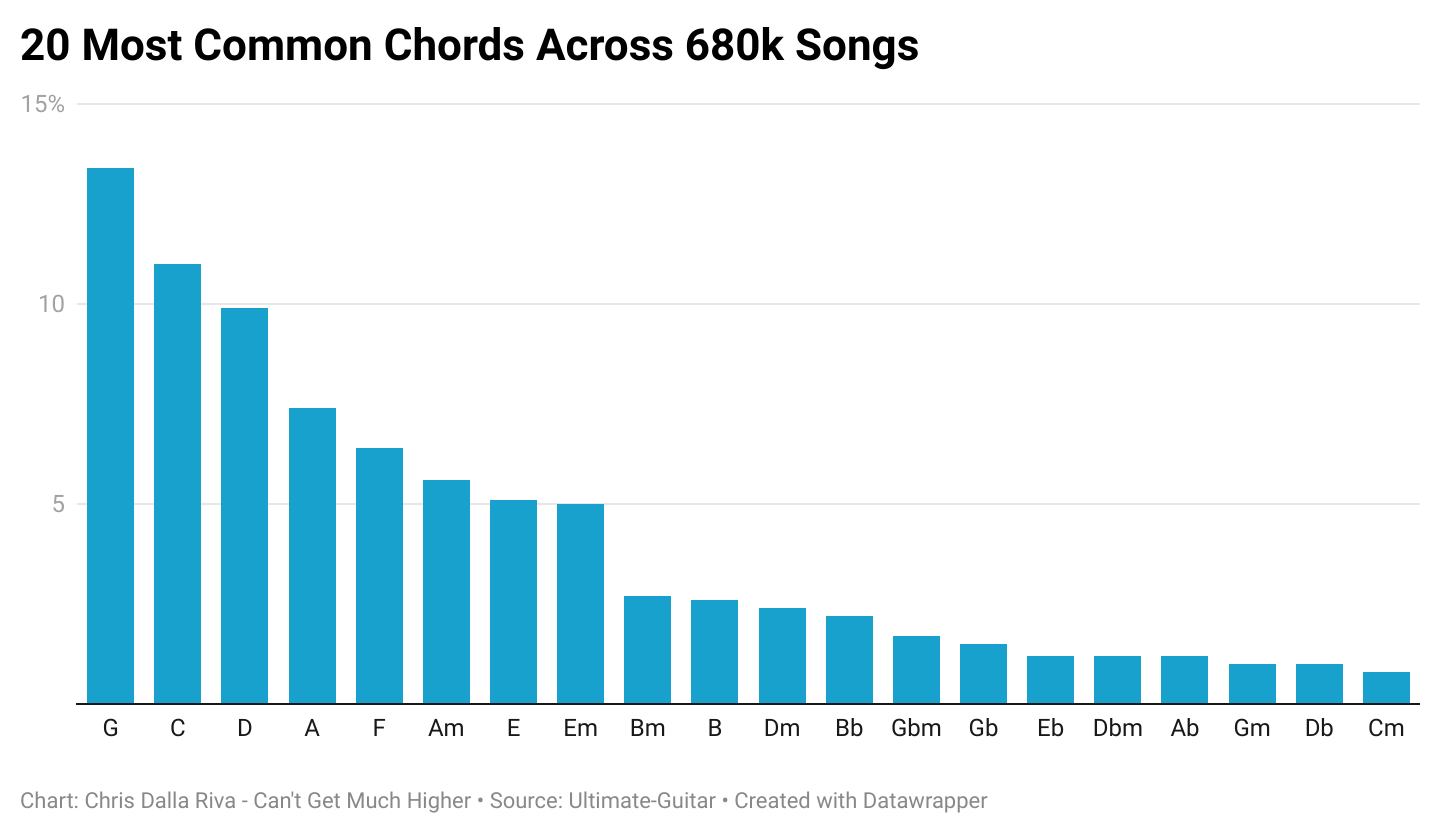

Above you can see a breakdown of the top 20 most common chords across the nearly 52 million chords notated in the Chordonomicon dataset. If you’ve ever played a guitar or piano, you won’t be surprised by the fact that G major and C major are at the top, accounting for 24% of all chords. These are some of the first chords you learn on those instruments. What’s interesting is that chord choices differ when you look across genre.

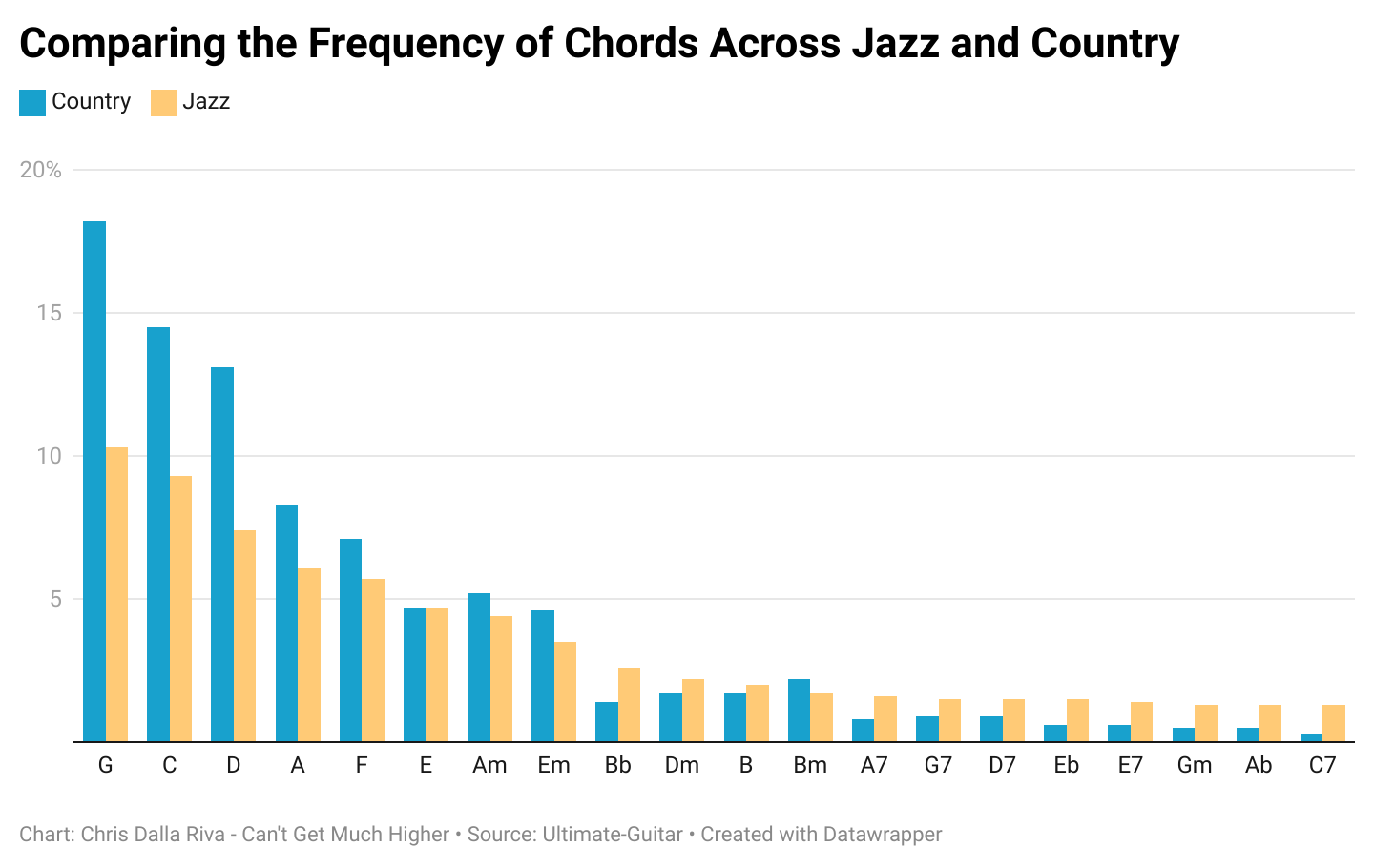

Below you can see a usage comparison of 20 common chords in jazz and country. The differences are stark. In country, for example, five major chords — G major, C major, D major, A major, and F major — comprise 61% of all chords played. Among jazz songs, by comparison, those chords only make up 39% of total chords. Nevertheless, if we take a look at some other chords, the relationship flips. Bb major, for example, makes up 2.6% of all chords in our jazz sample. For country, it’s 1.4%, almost half.

What explains these differences? Of course, some of it is connected to arbitrary compositional choices. But another piece is explained by the instruments used in each genre. For example, the trumpet is commonly used in jazz, and trumpets are tuned to Bb. Similarly, banjos and guitars are common in country. Banjos are tuned to open G, and, as noted, chords like G, C, and D are some of the first you will learn when picking up the guitar.

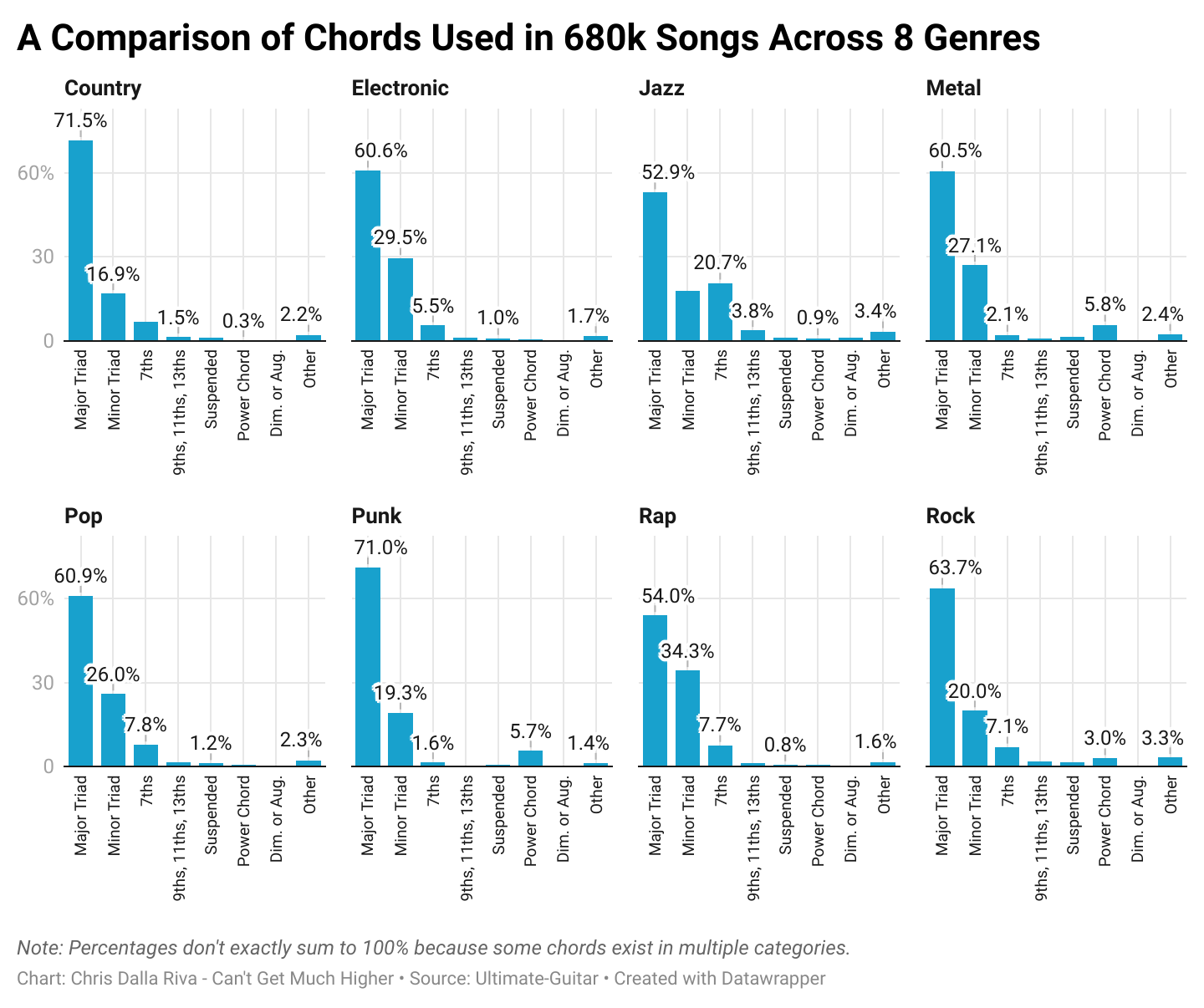

Looking at individual chords across a bunch of genres is a bit chaotic, though. Instead, we can group chords into a few categories to make cross-genre comparisons a bit more digestible. Below we can see that while your simple, three-note major chords (e.g., A major, Db major) are the most common across every genre, there are some stark differences in other categories. 7th chords, for example, are 2.5 to 13 times more common in jazz than any other genre. Similarly, power chords are 2 to 21.5 times more common in punk than any other genre. Furthermore, Suspended, diminished, and augmented chords basically don’t exist in rap.

But it’s not just interesting to compare these chord categories across genre. It’s interesting to compare them over time. Below you can see the prevalence of each chord type by decade from the 1930s to the 2020s. The most striking trend is that 7th chords have fallen into disuse. In the 1940s, 27.7% of all chords were 7th chords. Thus far in the 2020s, only 8.25% are. This decline is largely connected to the decline of jazz, a genre where the 7th chord family was a defining feature. As jazz has lost favor, simple minor triads (e.g., E minor, Ab minor) have become more prevalent.

Sunday, June 8, 2025

Milcho Leviev Quartet (feat. Art Pepper)

The Man in the Midnight-Blue Six-Ply Italian-Milled Wool Suit

A fine suit made just for me. From the best fabrics. By the best tailor. Paired with the best bespoke shoes.

A suit that would make me feel at ease, while declaring to others, “Here is a man who feels at ease.” A suit that would be appreciated by the world’s most heartless maître d’. A suit that would see me through the immigration checkpoints of difficult countries. A suit that would convince readers that the man in the author photo has a sense of taste beyond the Brooklyn consensus of plaid shirt and pouf of graying hair.

The suit would serve as the perfect carapace for a personality overly dependent on anxious humor and jaundiced wit, a personality that I have been trying to develop since I saw my lightly mustached punim in the mirror as a pubescent boy and thought, How will I ever find love? The suit would transcend my physicality and bond with my personality directly. It would accompany me through the world’s great salons, the occasional MSNBC appearance, and, most important, the well-compensated talks at far-flung universities. The suit would be nothing less than an extension of myself; it would be a valet preceding me into the room, announcing with a light continental accent, “Mr. Gary and his suit are here now.” Finding this perfect suit, made by the most advanced tailor out of superlative fabric, would do nothing less than transform me.

Before there is a suit, there is a body, and the body is terrible.

First there is my shortness (5 foot 5 and a half, with that “half” doing a lot of work). Being short is fine, but those missing inches are wedded to a narrow-shouldered body of zero distinction. Although I am of Russian and Jewish extraction, the continent whose clothing stores make me feel most at ease is Asia. (I once bought an off-the-rack jacket in Bangkok after the clerk examined me for all of three seconds.) However, this is not exactly an Asian body either, especially when I contrast myself with the natural slimness of most of my Asian friends. Just before my bar mitzvah, I got a set of perfect B-cup knockers and had to squeeze into a “husky” suit to perform the ritual yodeling at the synagogue. But that’s not all. Some hideously mismanaged childhood vaccination in Leningrad created a thick keloid scar running the length of my right shoulder. The shame of having this strange pink welt define one side of me led to a slumped posture favoring my left shoulder. When I finally found people to have sex with me—I had to attend Oberlin to complete the task—my expression upon disrobing resembled that of a dog looking up at his mistress after a bowel movement of hazmat proportions.

The clothes before the suit were as bad as the body.

I was born in the Soviet Union in 1972 and was quickly dressed in a sailor’s outfit with white tights and sexy little shorts, then given a balalaika to play with for the camera. The fact that Russia now fields one of the world’s most homicidal armies can partially be explained by photos such as this. On other occasions I was forced to wear very tight jogging pants with a cartoon bunny on them, or a thick-striped shirt dripping with medals from battles I had never seen. These outfits did make me feel like I belonged to something—in this case, a failing dictatorship. I left the U.S.S.R. before I could join the Young Pioneers, which would have entailed wearing a red tie at a tender age, while prancing about and shouting exuberant slogans such as “I am always ready!” (...)

Growing Up Tasteless

High school found me trying to blend in with a suburban outlay of clothes that my now middle-class family could finally afford. These were surfer T-shirts from Ocean Pacific and other brands that suburbanites who survived the 1980s might remember: Generra, Aéropostale, Unionbay. Unfortunately, I did not go to high school in Benetton Bay, Long Island, but in Manhattan, where these shirts were immediately a joke. (This would become a pattern. By the time I figure something out fashion-wise, I’m already two steps behind.) At a high-school job, my boss bought me a set of colorful Miami Vice–style shirts and jackets. These proved ridiculous at Oberlin, where dressing in janitor uniforms from thrift shops was considered the height of style. (Ironically, I had worked as a janitor during the summer, at the same nuclear laboratory that employed my father.)

After college, I fell in with a crowd of artsy, ketamine-addicted hipsters, and together we managed to gentrify several Brooklyn neighborhoods during the late ’90s. One of my friends, who was especially fashion-conscious, began to dress me at the high-priced secondhand emporium Screaming Mimis. The clothes she told me to buy were very itchy, mostly Orlon and Dacron items from ’70s brands such as Triumph of California, but these tight uniforms, like their Soviet predecessors, made me feel like I was playing a part in a grander opera, while also serving as a form of punishment. On nervous dates, I would sometimes have to run to the bathroom to try to angle my acrylic armpits under the dryer.

Because I was a writer who worked in bed, I mostly did not need a suit, although when I got married, in 2012, I went down to Paul Smith to get a herringbone number that I thought was just fine, if not terribly exciting. I bought a J.Crew tuxedo for black-tie benefits. Once, I did a reading sponsored by Prada and was given a nice gray jacket, pants, and a pair of blue suede shoes as compensation. Come to think of it, there was also a scarf. As a final note, I will say that I am incredibly cheap and that shopping for clothes has always raised my blood pressure. Leaving Screaming Mimis after spending more than $500 would always end in me getting terribly drunk to punish myself for the money I had blown on such a frivolous pursuit.

We met for dinner at Union Square Cafe, and I liked him (and his clothes) immediately. Mark was almost always dressed in a jacket and tie, and would often sport a vest along with spectacles made of some improbable metal. What I loved about him was how comfortable he appeared in his medley of classical attire, and how, despite the fact that all of his garments had been chosen with precision, he gave the impression that he had spent very little time and thought on which breathable fabrics to settle over his trim body. He looked like he was, to use my initial formulation, at ease.

Later, I would learn that this whole look could be summarized by the Italian word sprezzatura, or “studied carelessness,” and later still I learned of something that the Japanese had discovered and refined: “Ivy style,” which is basically studied carelessness goes to Dartmouth. For the time being, I knew that I liked what I saw, that my inner lonely immigrant—the one who is always trying to find a uniform that will help me fit in—was intrigued. Mark once gave me an Armoury safari jacket, the very same one worn by the character in my novel, and its light, unflappable linen proved perfect for my summer readings around Germany and Switzerland that year. Everywhere from starchy Zurich to drunken Cologne to cool-as-fuck Berlin, the jacket would pop out of a suitcase and unwrinkle itself in seconds, yet it was also stylish and seemingly impervious to the odors of my non-Teutonic body. It was, to use Hemingway-esque prose, damn well perfect, and I immediately knew I wanted more.

I had lived in Italy in my 30s and met many aristocrats there. Those bastards had sprezzatura to burn, but when I asked them the make of their suits and jackets, they would smile and tell me it was the work of a single tailor down in Naples or up in Milan. Ah, I would say to myself, so that’s how it is. Given my outlook on life, owning a bespoke suit was not an outcome I was predestined for. The Prada jacket I had been given, which fit me well enough, was the most that my Calvinist God would ever grant me.

But over more martinis and onglets au poivre with Mark, I began to understand the parameters of a fine bespoke suit and its accessories: bespoke shirts and bespoke shoes. I also began to timidly ask questions of a financial nature and learned that the price of owning such a wardrobe approached and then exceeded $10,000. I did not want to pay this kind of entry fee. Given my own family’s experience in fleeing a declining superpower, I try to have money saved with which to escape across the border. Unlike watches, a suit could not be resold in Montreal or Melbourne.The suit would be nothing less than an extension of myself; it would be a valet preceding me into the room, announcing with a light continental accent, “Mr. Gary and his suit are here now.”

A brief but generative conversation with my editors at this magazine soon paved the way for my dream to become possible. At a particularly unsober dinner with a visiting Japanese watchmaker, I whispered to Mark the extent of my desires. Yes, it would take a lot of work, a lot of research, and possibly travel to two other continents. But it could be done. At the right expense, with the most elegant and sturdy of Italian-milled fabrics, and with the greatest of Japanese tailors, a superior suit could be made for anyone, even for me. (...)

The British suit, in all its City of London severity, morphed into different shapes around the world. The Italians made particularly interesting work of it. The Milanese suit was the most British-like, but as you traveled farther down the boot to Florence, Rome, and Naples, the tailors became more freehanded; the colors and fit became jauntier and more Mediterranean, more appreciative of bodies defined by crooked lines and curves and exploded by carbohydrates. Meanwhile, in America, as always, we went to work. The suit became a uniform that stressed the commonality and goodness of Protestant labor and church attendance without any further embellishments. It came to be known as the “sack suit.” In the 1950s, Brooks Brothers furthered this concept with an almost subversively casual look: a jacket with natural-width shoulders that hung straight from the body, and plain-front trousers. This, along with other American touches, such as denim, became the basis for Ivy-style clothes that the Japanese of the ’60s made into a national obsession, and that culminated in a wholly different approach to workwear, office wear, and leisure wear. Today, you can’t go into a Uniqlo without seeing the aftereffects of Japanese experimentation with and perfection of our “Work hard, pray hard” wardrobe ethos.

I met Yamamoto-san at the Upper East Side branch of Mark Cho’s Armoury empire. The moment I first saw him, I was scared. No one could be this well-dressed. No one could be so secure in a tan three-piece seersucker suit that didn’t so much hang from his broad shoulders as hover around them in expectation. No one’s brown silk tie could so well match his brown polka-dot pocket square and the thick wedge of only slightly graying hair floating above his perfectly chiseled face. This man was going to make a suit for me? I was not worthy.

Yamamoto-san examined me briefly and said, “Sack suit.”

Image: Leung Man Hei and Dina Litovsky for The Atlantic

The Man Putin Couldn’t Kill

He identified the secret police agents behind one of the most high-profile assassination plots of all: the 2020 poisoning of the Russian opposition leader Aleksei Navalny. That revelation put Grozev in President Vladimir Putin’s cross hairs. He wanted Grozev killed, and to make it happen the Kremlin turned to none other than the fugitive financier, who, it turns out, had been recruited by Russian intelligence. Now the man that Grozev had been tracking began tracking him. The fugitive enlisted a team to begin the surveillance.

The members of that team are behind bars now. The financier lives in Moscow, where several times a week he makes visits to the headquarters of the Russian secret police. Grozev — still very much alive — imagines the man trying to explain to his supervisors why he failed in his mission. This gives Grozev a small measure of satisfaction.

On May 12, after a lengthy trial, Justice Nicholas Hilliard of the Central Criminal Court in London sentenced six people, all of them Bulgarian nationals, to prison terms between five and almost 11 years for their involvement in the plot to kill Grozev, among other operations. The group had spent more than two years working out of England, where the ringleader maintained rooms full of false identity documents and what the prosecution called law-enforcement-grade surveillance equipment. In addition to spying on Grozev and his writing partner, the Russian journalist Roman Dobrokhotov, the Bulgarians spied on a U.S. military base in Germany where Ukrainian soldiers were being trained; they trailed a former Russian law enforcement officer who had fled to Europe; and most embarrassingly for Moscow, they planned a false flag operation against Kazakhstan, a Russian ally.

In the past two decades England has been the site of at least two high-profile deadly operations and more than a dozen other suspicious deaths that have been linked to Russia. Yet the trial of this six-person cell appears to be the first time in recent history that authorities have successfully investigated and prosecuted Russian agents operating on British soil. The trial and its outcome, then, are victories. They are small ones, however, relative to the scope of the threat. The Bulgarians seem to be only one part of a multiyear, multicountry operation to kill Grozev. That in turn is only a small part of what appears to be an ever-broadening campaign by the Kremlin, including kidnappings, poisonings, arson and terrorist attacks, to silence its opponents and sow fear abroad.

The story of the resources that were marshaled to silence a single inconvenient voice is a terrifying reminder of what Putin, and beyond him the rising generation of autocratic rulers, are capable of. The story of how that single voice refused to be silenced — in fact redoubled his determination to tell the truth, regardless of the very real consequences — serves as a reminder that it’s possible to continue to speak and act in the face of mortal danger. But the damage that was done to Grozev’s own life and the lives of the people around him is a warning of how vulnerable we are in the face of unchecked, murderous power.

Saturday, June 7, 2025

Friday, June 6, 2025

Technology Does Not Solve Political Problems

In other words, do not hang out with tech people if you can help it.

Kidding! To some extent, this is just a tic of human nature—hanging out with media people will force you to endure endless conversations about news stories that imply that reality is little more than fodder for journalistic angles, which are what really matters. In the case of tech, though, the consequences can be worse than just tedium. That’s because the tech industry is uncommonly consequential to all of us—and the techno-utopian vision prevalent within the industry, which assumes that the world’s problems are a series of technological problems to be solved, and that technological progress is the key driver of increased human well-being, can therefore lead to uncommonly bad outcomes for society, when it turns out to be a critically incomplete understanding of how things work.

Alfred Nobel claimed to be surprised that his invention of dynamite contributed to war, not peace. Had to establish that Peace Prize to try to even the scales for all the dead bodies. This is as good a lesson as any for well-meaning tech industry people who possess a genuine belief that we can innovate our way out of social and political problems. We can’t. That’s because technology, while an extraordinarily powerful tool, does not by itself change the way that power is distributed in society. If the hand that holds the dynamite wants to use it to clear away rocks, you get great new roads. If the hand that holds the dynamite wants to use it to make bombs to drop on neighbors, you get mass death. If you say, “We’ll only give dynamite to peace-loving people,” the stronger, war-loving people will come and take it away. If you don’t change the overall power arrangement, new technology will just make strong people stronger. So too with today’s technologies. Except worse.

Consider the internet—the most transformative technology of my lifetime, so far. Tom Friedman and all of the other techno-utopians told me that the widespread availability of cheap high speed internet and smartphones would enable the cab driver in Djibouti to become an online entrepreneur just as easily as someone in Silicon Valley, and a new wave of equal opportunity would revolutionize the future of the world. Is that what happened? I don’t mean in an anecdotal sense, Is that the big socioeconomic story of the internet? No. The big socioeconomic story of the internet, despite all of the ways that it has changed our culture and entertainment and communication and Ways We Summon a Car, is that it has produced the biggest individual fortunes that the modern world has seen. It has, by any reasonable measure, increase inequality. It has consolidated more power in a smaller number of hands. Yeah, the Arab Spring was planned on Facebook. It failed. So were some genocides. They succeeded. In the past you had to buy a printing press to spread your words. Now you can publish things globally for free. Despite that fact, information control has become so centralized on a small number of platforms that the world’s richest man saw fit to spend $44 billion to buy a social media platform, and used it to help elect a fascist. All the guys who control the biggest tech companies, the ones that we were told would unleash a new World That Is Flat that would allow anyone anywhere to use these amazing new free or low-cost tools to compete with the well-funded big boys, ended up sitting behind the fascist on stage when he took the oath of office. Hey, whoa! Where did the internet age’s beautiful dream go off the rails?

The answer, of course, is that the belief that a radical new technology would produce a radical new world was always naive. Technology is not politics. It cannot solve political problems. It can, however, exacerbate political problems. The power of new technologies, controlled by the strong, makes them stronger. Obviously! I’m sure it sucked to get hit with a stick but it sucked even worse to get sliced in half with a hardened steel sword and even worse to be mowed down with a machine gun and even worse to have your whole city incinerated with an atomic bomb. All of these technologies have far more productive uses than war; but they were used for war because war is how strong people build and consolidate and maintain their own power. That is the thing that strong people do, above all. The internet doesn’t shoot you, but it has allowed strong people to create a total surveillance state and then guide missiles directly into your bedroom window, if they deem it necessary. Tom Friedman may protest that he was talking about other uses of the internet. Turns out that doesn’t matter. Great power concentrated in few hands means that those are the hands that will control the new technology. That means that the new technology will be used for their benefit. All visions of a sunny, technology-enabled bounteous future that do not grapple with this basic fact are doomed to be revealed, one day, as parodies of themselves.

This same pattern will hold true with AI, which is (presumably) the next great tech advance of our time. Absent very strong government regulation to prevent it, it is virtually certain that AI will lead to a greater concentration of wealth in fewer hands, as it replaces labor to the benefit of the investment class. To a lesser degree, the winners of this process will be the executives and (to an even lesser degree) the workers at the tech firms that produce and perfect the new technology. You don’t have to be much of a futurist to see this all coming. Nor do you have to be unreasonably grumpy to be a pessimist about the prospects of reining this in before it’s too late. Having watched this generation of big tech companies successfully avoid most meaningful regulation, the AI companies have a strong playbook to follow, and plenty of money to invest in removing all obstacles in their path. The Republican tax bill that just passed the House includes a provision blocking states from regulating AI for the next ten years. In ten years, it will be too late. All according to plan.

This is, I admit, a pretty grim vision for the nice regular people who work in tech. You liked computers and so you went to school for it and got a job at a big tech company and next thing you know you’re BUILDING THE EVIL PANOPTICON in exchange for a six figure salary and free lunch. The dark political outcome of this process is not what many of these workers thought they were signing up for. The good news is that there is something that these people can do that will meaningfully shift the balance of power that currently allows decisions of monumental global importance to be made by a few billionaires.

Max out donations to the Democratic Party? No. That’s not it. The thing is: unionize. I will tell you with no exaggeration that unions within the big tech companies would be the single strongest regulatory force in the entire tech industry, and I am including “government” and “Wall Street” in that statement. Wall Street is driven by the profit motive and therefore aligned with the project of unrestrained power for Big Tech. Government regulators are captured by tech money in politics, and seriously outgunned. But a unionized work force could, in fact, make demands about the pace and use and deployment of tech products, and—unlike any other force—would be be in a position to codify and enforce rules around all of these things. In the absence of government regulation, union contracts have thus far been the only things that have established any real rules around the use of AI. The few union contracts that have done so, however, have not covered companies that are actually building the technology. A union at Google or Facebook or OpenAI or other big tech firms would be in a position to negotiate rules about how AI could be used that would benefit all of society. The workers who build the product have an inherent power that no one else does. A union would allow them to wield that power. If you are a distraught tech worker searching for a way to avoid the bleak knowledge that your own prosperity comes at the cost of very scary downstream political consequences, organize your workplace.

Is that easy? No. Is it, however, within the realm of possibility? Yes. If you do not believe that workers can accomplish this, do you therefore believe that the United States government under Donald Trump will do a better job of responsibly regulating these technologies? No? Then I guess you’re leaving it all in the hands of the killer robots. Maybe this time will be different.

On Political Commitment

”What did you do when the poor suffered, when tenderness and life burned out of them?”

These lines are from the Guatemalan poet Otto René Castillo. (...)

Before his death, Castillo had just returned from exile in Europe in 1966 to become a propagandist for the Guatemalan Rebel Armed Forces. Soon after, he dropped the pen and picked up a rifle to fight. After he was captured by government forces, he was tortured and burnt alive in 1967.

Before the Scales, Tomorrow

And when the enthusiastic

story of our time

is told,

who are yet to be born

but announce themselves

with more generous face,

we will come out ahead

--those who have suffered most from it.

And that

being ahead of your time

means much suffering from it.

But it's beautiful to love the world

with eyes

that have not yet

been born.

And splendid

to know yourself victorious

when all around you

it's all still so cold,

so dark.

Castillo joined the Workers' Party of Guatemala at seventeen. In 1954, an army junta trained and financed by the U.S. government overthrew the democratically-elected Jacobo Arbenz after he had instituted agrarian reforms, which would have loosened the stranglehold of the United Fruit Company over Guatemala. The U.S. government mounted a full-on assault on Arbenz’s government, from economic sanctions to aerial bombings to radio propaganda. Like many of us from Latin America and elsewhere, Guatemalans are here because the U.S. was there. Like a friend once told me, “Puerto Ricans didn’t come to the United States. The United States came to Puerto Rico.”

Silvio Rodríguez - Sueño Con Serpientes

The song, with a surreal atmosphere, describes a nightmare that would be the metaphor of an obsession ( I kill it and a bigger one appears/with much more hell in digestion ).

Sueño Con Serpientes (I Dream of Snakes)

"There are men who fight for a day and are good.

There are others who fight for a year and are better.

There are those who fight for many years and are very good.

But there are those who fight all their lives.

Those are the indispensable ones."

Bertolt Brecht

I dream of snakes, of sea snakes

Of a certain sea, oh, I dream of snakes

Long, transparent, and in their bellies they carry

What they can snatch from love

Oh-oh-oh

I kill her and a bigger one appears

Oh-oh-oh-oh

With much more hell in digestion

I don't fit in her mouth, she tries to swallow me

But she gets stuck with a clover from my temple

I think she's crazy, I give her a dove to chew

and I poison her with my goodness

Oh-oh-oh

I kill her and a bigger one appears

Oh-oh-oh-oh

With much more hell in digestion

This one, at last, swallows me, and while I walk through its esophagus

I'm thinking about what will come

But it is destroyed when I reach its stomach, and I propose

With a verse, a truth

Oh-oh-oh

I kill her and a bigger one appears

Oh-oh-oh-oh

With much more hell in digestion

Oh-oh-oh

I kill her and a bigger one appears

Oh-oh

Thursday, June 5, 2025

What is Centrism?

But fascism is on the move, and secret police are snatching immigrants off the streets, and the blog wars feel a little beside the point right now. All of us, left and center alike, find ourselves now in the big, unwieldy boat labeled “The Opposition.” I know what the left wants: To tax the rich, to feed the poor, to increase equality, to free the unjustly imprisoned, to provide food and clothing and affordable housing and healthcare for all, winning the class war and smashing fascism along the way. Great. And… the centrists? What—besides successful podcasts and well-funded think tanks—do they want?

It became clear yesterday that the centrists have two primary messages, which contradict one another. The first message is, “We just need to do the common sense things that regular folks want.” The second message is, “Here are a bunch of highly paid Harvard-educated consultants to discuss what that is, statistically.” The entire event consisted of panels alternating between these two points. There was a presentation from the data engineer Lakshya Jain transmuting politicians into fantasy football participants, ranking every Democrat who had run for Congress by “Wins Above Replacement”—how much their vote share had exceeded statistical expectations for a Democrat in their district. This, he explained, was the definition of a “good candidate.” To drive home the point, Liam Kerr, the pollster co-hosting the event, appeared in a West Virginia Mountaineers football jersey in honor of Joe Manchin, the greatest Democratic candidate in modern history by this measure. What mattered was not “Is this candidate a fucking sellout?” but rather, “How statistically red of a district is it possible for anyone with a ‘D’ next to their name to win?”

Interspersed with all of this data were exhortations to Be Normal. Democrats need to “run people who know how to talk to ordinary people… soccer moms,” Jain said. If you ask anyone in the political world to define “ordinary people” and they answer “soccer moms,” it is a dead giveaway that they never interact with any ordinary people and think purely in branded demographic abstractions. The entire United States land mass would have to be covered with soccer fields and minivan parking to account for the number of soccer moms that exist in the minds of political consultants. Welcomefest consisted of professional consultants telling politicians, “Don’t sound like you listen to consultants!”, followed by politicians saying “Ya know in my district there in the Midwest, I talk to regular folks, not consultants.” This may all be of interest if you are trying to break into the lucrative field of consulting. As a recipe for saving America from dictatorship, though, it is pretty thin soup.

A related problem for centrism is that defining your own beliefs as What Normal People Believe leads to a whole lot of circular thinking. Guess which factions in politics believe they represent Common Sense Thinking? All of them! All of them believe that they speak for the sane, regular people who just want to live good lives and feed their families. I spent all day yesterday listening alertly for actual policy ideas to help me understand exactly what the centrists wanted, to distinguish them from the unrealistic wackos on the left. Matt Yglesias attempted to answer this with a slide deck criticizing allegedly bad Democratic policies including “Prolonged school closures during Covid,” “Paralysis on women’s sports,” “Refusal to discuss record oil production,” “Slow to act on the border,” and “Behind the curve on phonics.” But astute readers will notice that this is not a Data-Based Coherent Political Platform as much as it is just “A list of stuff that Matt Yglesias believes.” Everyone has one of those, and every pundit can stand on stage and talk their own book. What are the underlying principles? (...)

So…so? Is that all? Be normal, do normal stuff, don’t be awful, be decent to people? Does this add up to a philosophy? Is this the platform that inspired all of those billionaires to donate to all of those PACs? Is this the stuff that drew $50 million into the coffers of Third Way? Is this what drew all of these people into this ballroom at such an urgent historical moment? Is this what made me spend a nice sunny day surrounded by pasty lobbyists in all manner of herringbone blazers trying to chat up unfortunate 20-year-old interns? Why the fuck were we here? (...)

Setting aside the personality conflicts and the disingenuousness and the millions of dollars in PAC money fueling this whole charade, the most good faith reading of centrist philosophy is simply that Democrats should, above all, win. They should do their best to determine what a winning candidate and a winning platform looks like in any given district, and then do that, in order to get control of Congress and the White House and the government. As Matt Yglesias pointed out, if five more Blue Dog Democrats had been able to steal away Republican-leaning seats in the House in the last election, the entire destructive agenda of slashing Medicaid and food stamps in order to fund tax cuts for the rich—embodied in the Republican tax bill just passed by the House—would not be happening. In this formulation, subjugating any electorally unpopular political beliefs in order to win more seats is a moral imperative. If Joe Manchin represents the farthest left political position that the Democratic Party can hope to build a successful majority around, well, that is preferable to Donald Trump, isn’t it?

This plausible-sounding argument, however, collapses under the weight of its own execution. Welcomefest was full of data experts and pollsters explaining what was popular in the last election. Politicians were expected to use that data to determine their message for the next election. (While sounding normal!!) But data follows reality. It does not create it. The reason the Democratic Party is so profoundly unpopular today is that people do not know what it stands for. There is simply no way to change this by saying, “We will ask you all what you liked yesterday, and do that tomorrow.” In their pursuit of statistically bulletproof popularism, the centrists have their head so deep in data that it is impossible for them to have a vision. And that lack of a vision is the very thing that turns off the public. This is a political problem that is unsolvable by polling. It requires actual beliefs.