[ed. Justin Sandercoe (JustinGuitar) will always be my first choice (beginner to advanced, detailed theory and technique, great songs, all-around nice guy), with Dale Adams (tonedr of the amazing Lexington Lab Band) a close second. But I enjoy other teachers as well, like Marty Schwartz (here and here), Paul Davids (cheerful, optimistic), Steve Stein (Guitar Zoom), Rick Beato (check out his Steely Dan tutorials and commentaries), David Taub (rockongoodpeople), and jazz, latin and other genres. What a great resource (for free!) YouTube lessons like these (along with accurate and cheap tuners like Snark and others) have been revolutionary in making guitar learning easy and accessible to everyone.]

Saturday, November 23, 2019

Friday, November 22, 2019

Boo-Hoo Billionaires

The 1996 US election was all about the “soccer mom”; 2004 belonged to the “Nascar dads”; Donald Trump won the White House with a “basket of deplorables”. Every election cycle seems to have a key demographic said to define the race, and 2020 is no different. This is the campaign of the “boo-hoo billionaire”.

There’s a billionaire in the White House and two of the top Democratic rivals for Trump’s job, senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, have made ever-widening income inequality central to their campaign.

“I don’t think that billionaires should exist,” Sanders said recently, citing the “immoral level of income and wealth inequality” that has only deepened under the Trump administration.

“I don’t think that billionaires should exist,” Sanders said recently, citing the “immoral level of income and wealth inequality” that has only deepened under the Trump administration.One billionaire bid for the White House has already flamed out. Howard Schultz, Starbuck’s former barista-in-chief, ended his run almost as soon as it had begun chased away by angry crowds who labeled him an “egotistical billionaire asshole!”

That hasn’t stopped another billionaire, hedge-fund mogul Tom Steyer, running for the Democratic nomination. And now former New York mayor Mike Bloomberg, founder of the eponymous media empire, is also making moves to enter the race, fired up by the billionaire bashing. Ironically, Bloomberg (net worth $52.3bn) signaled his intention to get in the race by getting his name on the ballot in Alabama, one of the poorest states in the union with a median household income of $48,123.

Kevin Kruse, professor of history at Princeton University and co-author of Fault Lines: A History of the United States Since 1974, believes there’ll be more to come. “The Trump candidacy made a lot of them think, ‘Well, if this guy with his inherited wealth, who went bankrupt all the time, if he can do it, why not me?’”

The mistake they make is ignoring Trump’s charisma and “huckster showmanship”, said Kruse. “They think because they have even more money they will have more charisma. That’s not the case, It wasn’t with Schultz, it isn’t with Steyer and it’s not going to be with Bloomberg,” he said. “The idea that Mike Bloomberg is going to do well in Alabama is insane.”

That’s not what the billionaires think. As Warren and Sanders have stepped up their attacks, a host of plutocrats have gone public with their anger at all this billionaire-bashing, and some are already coming out for Bloomberg.

For them, this is personal. The “great plute freakout of 2019” as Anand Giridharadas, the author of Winner Takes All, a recent study of the deleterious impact of elites, has called it, is literally reducing billionaires to tears.

Asked about his views on the 2020 election on CNBC earlier this month, moist-eyed investment giant Leon Cooperman, worth $3.2bn according to Forbes, could barely hold back the tears.

“I care. That’s it,” he sobbed, eyes cast down and shuffling papers.

Cooperman has clashed with Warren in recent months after she proposed higher taxes on the super wealthy. “I believe in a progressive income tax and the rich paying more. But this is the fucking American dream she is shitting on,” Cooperman told Politico. (...)

But that won’t stop the billionaires from wanting to add 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue to their property portfolio – even if the peasants have gathered with their pitchforks at the gates.

“There is something about the very wealthy, they don’t have enough people telling them that they are full of shit,” said Kruse.

by Dominic Rushe, The Guardian | Read more:

Image: Scott Eisen/Getty Images

[ed. By the way, $52 billion = 52,000 millions. See also: Ok Billionaire: Why Do the Opinions of 600 Americans Get So Much Airtime? (LitHub).]

How to Make the Perfect Popcorn

My popcorn memories go back to when I was ten years old, excavating the depths of a giant metal bowl in small-town New York state. Each Sunday, with Godzilla or James Bond blowing things up on TV, my dad filled this bowl with popcorn. My brothers and I passed it around like an enormous communion chalice. The only things we fought over were the slightly popped kernels at the bottom. We knew better than to ignore them as “failed popcorn.” These were nuggets of pure flavour.

Think of the difference between boiled and fire-roasted corn on the cob. Boiled is still corn . . . but is it the best corn it can be? No. It’s secretly ashamed of itself. The popcorn I’m talking about—the Platonic ideal of popped corn—is nutty, browned, toasted, and crunchy, with a sliver of kernel breaking through the crust.

Think of the difference between boiled and fire-roasted corn on the cob. Boiled is still corn . . . but is it the best corn it can be? No. It’s secretly ashamed of itself. The popcorn I’m talking about—the Platonic ideal of popped corn—is nutty, browned, toasted, and crunchy, with a sliver of kernel breaking through the crust.But the half-popped kernels of my youth were tooth-chipping land mines, and I’m not a ten-year-old watching Godzilla anymore. (I’m a fifty-two-year-old watching Godzilla.) My entire life, I have searched for a way to get that amazing taste in a more dental-friendly form. Along the way, I chipped two teeth and almost burned down an apartment with oil. Now that I’ve found a combination of the right process and the right kernels, I eat popcorn at least four nights a week—sometimes for dinner.

Ignore the first thing that pops into your head when you think of popcorn (likely Orville Redenbacher). The kernels used by such commercial brands are too big. The moisture inside a kernel is what makes it pop, and these have way too much moisture: the popped kernels end up like Styrofoam. After years of trial and error, I’m convinced the best variety of corn is Amish Country Lady Finger hulless [ed. here or here]. Each kernel, if handled well, turns into a tiny, almost perfect explosion of taste. A wave of melted butter enhances the flavour. Hell, you don’t even need butter.

Using the proper popping technique is key. Microwave is out of the question. Oil (in a pot or pan on the stove) is fine, but it leaves an oily taste that masks the corn flavour. There’s only one way to release the kernels’ hidden treasures: pre-pop them, then air-pop them.

by Kevin Sylvester, The Walrus | Read more:

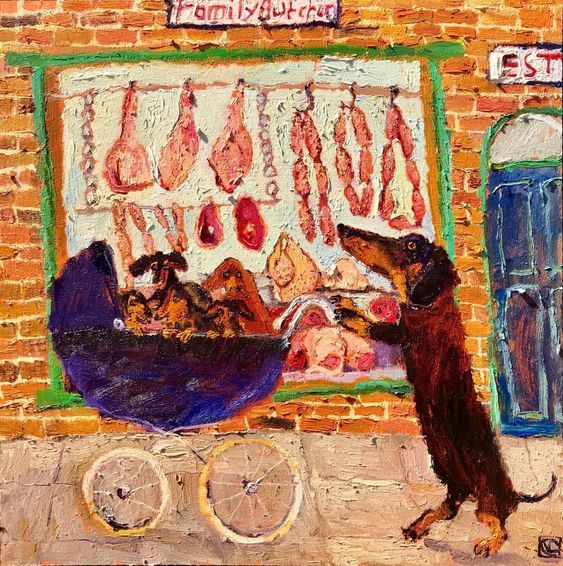

Image: Tallulah Fontaine

Back to the Future

Found in the the University of Washington Libraries's Special Collections, this 1898 photo of badass climate activist Greta Thunberg proves that she is a time traveler who is here to save us from ourselves. Or, perhaps Twitter user @bucketofmoney is correct: "The Greta Thunberg time-travel conspiracy theorists have got it wrong: the photo is from the future."

Thursday, November 21, 2019

The Nature of Creepiness

These days, ‘creepy’ is a popular pejorative. From ‘Creepy Uncle Joe’ Biden’s hair-smelling antics to Justin Trudeau standing ‘too close’ to a tennis star, from the random dude who just slid into your direct messages to Zach Braff holding hands with a much-younger actress, many people are invoking creepiness as a factor, even a decisive one, in considerations about what is socially acceptable and even who is fit for political office. Creeps, it seems, are everywhere.

It’s a strange development. Why are we calling so many people, usually men, creepy? Despite the prevalence of the creepiness discourse, real research into the nature of creepiness is pretty new. It suggests that creepiness is related to disgust, which is an adaptive emotional response that helps to maintain a physical barrier between our bodies and potentially injurious external substances. Disgust assists us in policing the line between inside and outside our bodies, but also to create and maintain interpersonal and social borders. Physical reactions – such as the shudder response, nausea, and exclamations of ‘ew’, ‘icky’ and ‘gross’ – can be important ways of producing and transmitting commitments to social norms. Signalling disgust helps society maintain the integrity of taboos around sexuality, including paedophilia and incest.

Biologically, being grossed out by, for example, the idea of ingesting faeces makes sense: it keeps us from getting ill. Feeling ‘creeped out’ by a person or a social situation, however, is less straightforward. Creepiness is different from disgust in that it refers to a feeling of unease in the face of social liminality, particularly where sex and death are involved. We become uncomfortable when events don’t easily fit our expectations or transgress social rules. In a 2016 study, the psychologists Francis McAndrew and Sara Koehnke at Knox College in Illinois concluded that ‘creepiness is anxiety aroused by the ambiguity of whether there is something to fear or not and/or by the ambiguity of the precise nature of the threat’. Emotionally, creepiness helps us externalise our internal sense of confusion and uncertainty when presented with situations that are not easily categorised. Feeling ‘creeped out’ justifies our decision to shut down, rather than undertake the task of analysing ambiguously threatening situations. It is a form of cognitive paralysis indicating that we are unsure how to proceed.

Biologically, being grossed out by, for example, the idea of ingesting faeces makes sense: it keeps us from getting ill. Feeling ‘creeped out’ by a person or a social situation, however, is less straightforward. Creepiness is different from disgust in that it refers to a feeling of unease in the face of social liminality, particularly where sex and death are involved. We become uncomfortable when events don’t easily fit our expectations or transgress social rules. In a 2016 study, the psychologists Francis McAndrew and Sara Koehnke at Knox College in Illinois concluded that ‘creepiness is anxiety aroused by the ambiguity of whether there is something to fear or not and/or by the ambiguity of the precise nature of the threat’. Emotionally, creepiness helps us externalise our internal sense of confusion and uncertainty when presented with situations that are not easily categorised. Feeling ‘creeped out’ justifies our decision to shut down, rather than undertake the task of analysing ambiguously threatening situations. It is a form of cognitive paralysis indicating that we are unsure how to proceed.Because women are more likely than men to experience physical and sexual threat in their daily lives, they are also more likely to judge others (usually men) to be creepy. Judgments of creepiness, however, are not necessarily reliable.

Conventional wisdom tells us to ‘trust our gut’, but researchers say that our gut is concerned more with regulating the boundaries of social mores than keeping us safe. In a 2017 Canadian study, female undergraduates were shown images of Caucasian male faces from three groups: emotionally neutral faces taken from an image bank; images judged ‘creepy’ in a pilot study; and images of criminals from America’s Most Wanted. They were then asked to rate the faces according to creepiness, trustworthiness and attractiveness. Across all three groups, there was a strong correlation between faces that participants considered trustworthy and attractive, and in some instances general attractiveness was negatively correlated with judgments of creepiness. Further, the faces taken from America’s Most Wanted were not rated as significantly more creepy than the neutral group. Participants made their creepiness assessments in seconds, and reported high degrees of confidence in their judgments.

Participants thought that, rather than describing behaviours, creepiness adhered to certain kinds of people and occupations. This is important.

Unkempt and dirty men, men with abnormal facial features, and men between the ages of 31-50 were all very likely to be rated creepy. Furthermore, creepiness was positively correlated both with the belief that the person held a sexual interest in the person making the social judgment, and with individuals who engaged in non-normative behaviours. This finding aligns with the McAndrew and Koehnke study, in which clowns, sex-shop owners and those interested in taxidermy were among the creepiest kinds of people.

So rather than reliably detecting danger, our internal ‘spidey sense’ often signals social difference or otherness. When we judge a situation or person creepy, we participate in shunning and social ostracism. Creepiness can prevent us from responding to the odd, the new or the peculiar with curiosity, interest and generosity of spirit. (...)

What does this tell us about how we should think about creepiness when it comes to a co-worker, a politician or a celebrity? To date, little has been written about the social and psychological mechanisms that make #MeToo allegations compelling. But it has become common and acceptable to publicly evaluate and judge sexual conduct and experiences according to the capacious affective language of disgust. Today, sex that leaves a woman ‘feeling gross’, or sexually non-normative behaviour that reads as ‘creepy’, can be enough to cast a man out of polite society.

Much of the #MeToo movement purports to focus on bad behaviour; namely, the violation of the requirement of consent in sexual encounters. On its face, #MeToo discourse relies heavily on the supposedly clear line between consent and violation, where the trouble presented by ‘grey areas’ is understood to be fixable if only we better understood – and were more publicly aware of – the nature of consent. But for all the talk about the importance of consent, there is another slippery process at work under the surface. Here, the affective vector of creepiness allows us to express our discomfort with an age-gap relationship or a request for a masturbation audience, even in situations where consent is present.

Creepiness research shows us that our perceptual intuitions about people and situations are at least as important – and perhaps more important than – cognitive judgment based on bad conduct. The line between sex and assault – the line marked by consent – is just one place where evaluation occurs. A sexual encounter can be intensely creepy – and entirely legal.

by Heidi Matthews, Aeon | Read more:

Image: Boris Thaser/Flickr

[ed. Taxidermy?]

Delisting Chinese Firms From U.S. Is a ‘Terrible Idea’

Paulson, who’s now chairman of the Paulson Institute, told Bloomberg’s New Economy Forum in Beijing that moves to reduce ties between the U.S. and China would weaken American leadership and New York’s leading role in finance. He said less cooperation between Washington and Beijing would also make it more difficult to tackle another financial crisis like the one he was forced to manage as treasury secretary in 2008.

Paulson, who’s now chairman of the Paulson Institute, told Bloomberg’s New Economy Forum in Beijing that moves to reduce ties between the U.S. and China would weaken American leadership and New York’s leading role in finance. He said less cooperation between Washington and Beijing would also make it more difficult to tackle another financial crisis like the one he was forced to manage as treasury secretary in 2008.“When the next crisis comes -- and a crisis will come, because financial crises are inevitable -- we will regret it if we lack mechanisms for the world’s first and second-largest economies to coordinate,” Paulson told the forum on Thursday, according to a prepared version of his remarks.

Paulson’s speech followed on from his warning at the same forum last year that an “economic iron curtain” was descending between the U.S. and Chinese economies. Since then, the relations between the two sides have grown even more strained by trade disputes, security spats and disagreement over human rights.

The Trump administration has been pressuring allies to stop using Chinese technology. U.S. officials are also discussing ways to limit American investors’ portfolio flows into China, Bloomberg News reported in September, citing people familiar with the internal deliberations.

The U.S. Treasury said that there was no plan “at this time” to block Chinese companies from listing on U.S. stock exchanges.

by Bloomberg News, Yahoo News | Read more:

Image: uncredited

[ed. One might reasonably ask, "What the hell is he talking about, and why should I care?" Well, wonder no more: to protect Wall Street scammers (of course). See: Chinese Stock Collapses 98% in Hours After MSCI Flip-Flops: How Index Providers Saddle US Pension Funds with Stock Scams (Wolf Street).]

Cement Has a Carbon Problem

What accounts for that jaw-dropping carbon footprint? To make cement, you have to heat limestone to nearly 1,500 degrees C. Unfortunately, the most efficient way to get a cement kiln that hot is to burn lots of coal, which, along with other fossil fuel energy sources, accounts for 40 percent of the industry’s emissions. Eventually, the limestone breaks down into calcium oxide (also known as lime) and releases CO2, which goes straight into the atmosphere, accounting for a further 60 percent of the industry’s emissions.

The good news is that there’s no shortage of ideas for how to slim down cement’s weighty carbon footprint. The bad news is that most of them are either in their infancy or face significant barriers to adoption. As our window of time for preventing catastrophic climate change grows ever smaller, we need major investments in new technologies and changes to how the cement industry works. But most of all, we need politicians need to wake up to the fact that the cement industry has a climate problem. (...)

The good news is that there’s no shortage of ideas for how to slim down cement’s weighty carbon footprint. The bad news is that most of them are either in their infancy or face significant barriers to adoption. As our window of time for preventing catastrophic climate change grows ever smaller, we need major investments in new technologies and changes to how the cement industry works. But most of all, we need politicians need to wake up to the fact that the cement industry has a climate problem. (...)Developing new cement manufacturing technologies is only half the battle against cement’s carbon emissions. The other half is finding ways to use less cement.

Today the world churns out 4 billion tons of cement every year, or about 1,200 pounds for every human being alive. As more people move into cities, developing countries modernize their infrastructure, and the world transitions to new energy systems, our appetite for cement is only expected to grow. By 2050, we could be cooking up close to 5 billion tons of cement a year.

“As with everything in climate change, the most salient aspect of the problem is its scale,” said Rebecca Dell, an industry strategist with ClimateWorks. “If cement were a niche material this wouldn’t be a problem.”

by Maddie Stone, Grist | Read more:

Image: Avalon Studio/Getty ImagesHow Boeing Lost It's Bearings

The flight that put the Boeing Company on course for disaster lifted off a few hours after sunrise. It was good flying weather—temperatures in the mid-40s with a slight breeze out of the southeast—but oddly, no one knew where the 737 jetliner was headed. The crew had prepared three flight plans: one to Denver. One to Dallas. And one to Chicago.

In the plane’s trailing vortices was greater Seattle, where the company’s famed engineering culture had taken root; where the bulk of its 40,000-plus engineers lived and worked; indeed, where the jet itself had been assembled. But it was May 2001. And Boeing’s leaders, CEO Phil Condit and President Harry Stonecipher, had decided it was time to put some distance between themselves and the people actually making the company’s planes. How much distance? This flight—a PR stunt to end the two-month contest for Boeing’s new headquarters—would reveal the answer. Once the plane was airborne, Boeing announced it would be landing at Chicago’s Midway International Airport.

On the tarmac, Condit stepped out of the jet, made a brief speech, then boarded a helicopter for an aerial tour of Boeing’s new corporate home: the Morton Salt building, a skyscraper sitting just out of the Loop in downtown Chicago. Boeing’s top management plus staff—roughly 500 people in all—would work here. They could see the boats plying the Chicago River and the trains rumbling over it. Condit, an opera lover, would have an easy walk to the Lyric Opera building. But the nearest Boeing commercial-airplane assembly facility would be 1,700 miles away.

On the tarmac, Condit stepped out of the jet, made a brief speech, then boarded a helicopter for an aerial tour of Boeing’s new corporate home: the Morton Salt building, a skyscraper sitting just out of the Loop in downtown Chicago. Boeing’s top management plus staff—roughly 500 people in all—would work here. They could see the boats plying the Chicago River and the trains rumbling over it. Condit, an opera lover, would have an easy walk to the Lyric Opera building. But the nearest Boeing commercial-airplane assembly facility would be 1,700 miles away.The isolation was deliberate. “When the headquarters is located in proximity to a principal business—as ours was in Seattle—the corporate center is inevitably drawn into day-to-day business operations,” Condit explained at the time. And that statement, more than anything, captures a cardinal truth about the aerospace giant. The present 737 Max disaster can be traced back two decades—to the moment Boeing’s leadership decided to divorce itself from the firm’s own culture.

For about 80 years, Boeing basically functioned as an association of engineers. Its executives held patents, designed wings, spoke the language of engineering and safety as a mother tongue. Finance wasn’t a primary language. Even Boeing’s bean counters didn’t act the part. As late as the mid-’90s, the company’s chief financial officer had minimal contact with Wall Street and answered colleagues’ requests for basic financial data with a curt “Tell them not to worry.”

By the time I visited the company—for Fortune, in 2000—that had begun to change. In Condit’s office, overlooking Boeing Field, were 54 white roses to celebrate the day’s closing stock price. The shift had started three years earlier, with Boeing’s “reverse takeover” of McDonnell Douglas—so-called because it was McDonnell executives who perversely ended up in charge of the combined entity, and it was McDonnell’s culture that became ascendant. “McDonnell Douglas bought Boeing with Boeing’s money,” went the joke around Seattle. Condit was still in charge, yes, and told me to ignore the talk that somebody had “captured” him and was holding him “hostage” in his own office. But Stonecipher was cutting a Dick Cheney–like figure, blasting the company’s engineers as “arrogant” and spouting Harry Trumanisms (“I don’t give ’em hell; I just tell the truth and they think it’s hell”) when they shot back that he was the problem.

McDonnell’s stock price had risen fourfold under Stonecipher as he went on a cost-cutting tear, but many analysts feared that this came at the cost of the company’s future competitiveness. “There was a little surprise that a guy running a failing company ended up with so much power,” the former Boeing executive vice president Dick Albrecht told me at the time. Post-merger, Stonecipher brought his chain saw to Seattle. “A passion for affordability” became one of the company’s new, unloved slogans, as did “Less family, more team.” It was enough to drive the white-collar engineering union, which had historically functioned as a professional debating society, into acting more like organized labor. “We weren’t fighting against Boeing,” one union leader told me of the 40-day strike that shut down production in 2000. “We were fighting to save Boeing.”

Engineers were all too happy to share such views with executives, which made for plenty of awkward encounters in the still-smallish city that was Seattle in the ’90s. It was, top brass felt, an undue amount of contact for executives of a modern, diversified corporation.

One of the most successful engineering cultures of all time was quickly giving way to the McDonnell mind-set. Another McDonnell executive had recently been elevated to chief financial officer. (“A further indication of who in the hell was controlling this company,” a union leader told me.) That, in turn, contributed to the company’s extraordinary decision to move its headquarters to Chicago, where it strangely remains—in the historical capital of printing, Pullman cars, and meatpacking—to this day.

If Andrew Carnegie’s advice—“Put all your eggs in one basket, and then watch that basket”—had guided Boeing before, these decisions accomplished roughly the opposite. The company would put its eggs in three baskets: military in St. Louis. Space in Long Beach. Passenger jets in Seattle. And it would watch that basket from Chicago. Never mind that the majority of its revenues and real estate were and are in basket three. Or that Boeing’s managers would now have the added challenge of flying all this blind—or by instrument, as it were—relying on remote readouts of the situation in Chicago instead of eyeballing it directly (as good pilots are incidentally trained to do). The goal was to change Boeing’s culture.

And in that, Condit and Stonecipher clearly succeeded. In the next four years, Boeing’s detail-oriented, conservative culture became embroiled in a series of scandals. Its rocket division was found to be in possession of 25,000 pages of stolen Lockheed Martin documents. Its CFO (ex-McDonnell) was caught violating government procurement laws and went to jail. With ethics now front and center, Condit was forced out and replaced with Stonecipher, who promptly affirmed: “When people say I changed the culture of Boeing, that was the intent, so that it’s run like a business rather than a great engineering firm.” A General Electric alum, he built a virtual replica of GE’s famed Crotonville leadership center for Boeing managers to cycle through. And when Stonecipher had his own career-ending scandal (an affair with an employee), it was another GE alum—James McNerney—who came in from the outside to replace him.

As the aerospace analyst Richard Aboulafia recently told me, “You had this weird combination of a distant building with a few hundred people in it and a non-engineer with no technical skills whatsoever at the helm.” Even that might have worked—had the commercial-jet business stayed in the hands of an experienced engineer steeped in STEM disciplines. Instead McNerney installed an M.B.A. with a varied background in sales, marketing, and supply-chain management. Said Aboulafia, “We were like, ‘What?’’’

by Jerry Useem, The Atlantic | Read more:

Image: Hermes Images/AGF/Universal Images Group/Getty

Meals on Broken Wheels

What do DoorDash, GrubHub, Postmates and Uber Eats have in common with Lassie? Nothing. They’re dogs; Lassie’s a superstar. What do they have in common with each other? Everything. They take the world’s second oldest profession — Babylonia had delivery boys — sprinkle it with tech dust, click their ruby slippers, chant “There’s no place like Silicon Valley” and hope to become unicorns. (By the way, since unicorns are entirely mythical, wouldn’t the Valley be wise to pick another moniker for its wannabe superstars?)

There’s no secret to success in tech. But like hitting a 98 mph fastball, it’s easy to describe, nearly impossible to do: Create a great product that can scale. Even better if you can build a patent moat around it. If, after five hard years of R&D, you create killer software at a cost of $100 million, then the first product you ship for $1,000 comes at a loss of $99.99 million. But by the time you’ve sold your millionth unit at almost no additional cost, you’ve grossed a billion. That’s scale.

Here’s the rub: You can scale intellectual property, you can’t scale labor. Your millionth pizza costs as much to deliver as your first.

Yet the meal-delivery guys claim they will scale when they create a critical mass. They will have the density they need to become profitable (none are yet) if they can somehow bag a huge market share. The density argument goes like this: if we can deliver enough meals in a given trade area, we can be like the post office in terms of efficiency (yes, the post office, I’m not being ironic). Nice idea, but it doesn’t wash.

The post office is a route business—your mail carrier hits the same couple hundred houses on the identical route every day. That beats 200 homeowners making 200 trips to the post office.

Meal delivery is a discrete business. No one else in your zip code is ordering spaghetti Bolognese from Trattoria Pastaria at 6:30 on a Tuesday evening. Whether the Uber Eats guy drives to the restaurant or you do, it’s the same (except the food is hotter if you do it yourself). There is no way to string that discrete delivery into an efficient, cost-effective route. To that point, old-school pizza joints average about 2 deliveries an hour and their drivers start at the restaurant. Can a free-floating DoorDasher do more than two an hour?

In short, Mount Everest is scalable, meal-delivery companies are not.

This claim of eventual profitability calls to mind the very old joke about the jeweler who sold his diamonds below cost, losing a little on each sale. “I make it up in volume,” he said. He didn’t and neither will the meal-delivery companies.

Let’s get specific. DoorDash, Postmates and Uber Eats all deliver for McDonald’s. According to that most reliable of all sources, the internet, they charge about $5 to deliver your burger and fries. And it takes about 30 minutes from the time you order to delivery. This means that, like pizza, the driver can do about two trips an hour. This is a truly great service for the consumer too stoned to get his own milkshake at midnight.

But there is no way, no way, in the world this can be profitable for the meal-delivery companies (or the restaurants if they do it themselves). Ten bucks an hour won’t even pay for the driver’s gas and minimum wage, let alone his incidental car costs. What’s left for DoorDash on ten bucks an hour? Nothing.

There’s no secret to success in tech. But like hitting a 98 mph fastball, it’s easy to describe, nearly impossible to do: Create a great product that can scale. Even better if you can build a patent moat around it. If, after five hard years of R&D, you create killer software at a cost of $100 million, then the first product you ship for $1,000 comes at a loss of $99.99 million. But by the time you’ve sold your millionth unit at almost no additional cost, you’ve grossed a billion. That’s scale.

Here’s the rub: You can scale intellectual property, you can’t scale labor. Your millionth pizza costs as much to deliver as your first.

Yet the meal-delivery guys claim they will scale when they create a critical mass. They will have the density they need to become profitable (none are yet) if they can somehow bag a huge market share. The density argument goes like this: if we can deliver enough meals in a given trade area, we can be like the post office in terms of efficiency (yes, the post office, I’m not being ironic). Nice idea, but it doesn’t wash.

The post office is a route business—your mail carrier hits the same couple hundred houses on the identical route every day. That beats 200 homeowners making 200 trips to the post office.

Meal delivery is a discrete business. No one else in your zip code is ordering spaghetti Bolognese from Trattoria Pastaria at 6:30 on a Tuesday evening. Whether the Uber Eats guy drives to the restaurant or you do, it’s the same (except the food is hotter if you do it yourself). There is no way to string that discrete delivery into an efficient, cost-effective route. To that point, old-school pizza joints average about 2 deliveries an hour and their drivers start at the restaurant. Can a free-floating DoorDasher do more than two an hour?

In short, Mount Everest is scalable, meal-delivery companies are not.

This claim of eventual profitability calls to mind the very old joke about the jeweler who sold his diamonds below cost, losing a little on each sale. “I make it up in volume,” he said. He didn’t and neither will the meal-delivery companies.

Let’s get specific. DoorDash, Postmates and Uber Eats all deliver for McDonald’s. According to that most reliable of all sources, the internet, they charge about $5 to deliver your burger and fries. And it takes about 30 minutes from the time you order to delivery. This means that, like pizza, the driver can do about two trips an hour. This is a truly great service for the consumer too stoned to get his own milkshake at midnight.

But there is no way, no way, in the world this can be profitable for the meal-delivery companies (or the restaurants if they do it themselves). Ten bucks an hour won’t even pay for the driver’s gas and minimum wage, let alone his incidental car costs. What’s left for DoorDash on ten bucks an hour? Nothing.

by John E. McNellis, Wolf Street | Read more:

[ed. See also: Silicon Valley Is Slowing, Whether for a Quick Breather or Extended Time-Out, I Have No Idea (Wolf Street).]

How Home Delivery Reshaped the World

A lot of attention has rightly been paid to the toll that fulfilling our orders takes upon workers in warehouses or drivers in delivery vans. But additionally, as our purchases hurtle towards us in ever-higher volumes and at ever-faster rates, they exert an unseen, transformative pressure – on infrastructure, on cities, on the companies themselves. “The customer is putting an enormous strain on the supply chain,” said James Nicholls, a managing partner at Stephen George + Partners, an industrial architecture firm. “Especially if you are ordering a thing in five different colours, trying them all on, and sending four of them back.”

How the pressures of home delivery reorder the world can be understood best through the “last mile” – which is not strictly a mile but the final leg that a parcel travels from, say, Magna Park 3 to a bedsit in Birmingham. The last mile obsesses the delivery industry. No one in the day-to-day hustle of e-commerce talks very seriously about the kind of trial-balloon gimmicks that claim to revolutionise the last mile: deliveries by drones and parachutes and autonomous vehicles, zeppelin warehouses, robots on sidewalks. Instead, the most pressing last-mile problems feel basic, low-concept, old-school. How best to pack a box. How to beat traffic. What to do when a delivery driver rings the doorbell and no one is home. What to do with the forests of used cardboard. In home delivery, the last mile has become the most expensive and difficult mile of all. (...)

E-commerce has turned even the laying of a floor into a fiendishly involved business. The concrete floors of B2B sheds were already being built to an exacting degree of flatness, calibrated using lasers, so that forklifts would not teeter while lifting pallets to the highest shelves. As the urgency of home delivery grew, robotic pickers began to populate e-commerce sheds, so the floors had to be flatter still – first poured to a standard called FM2, and the robots’ aisles then ground down further to FM1. In these “superflat floors”, even a 10th of a millimetre matters. The merest waywardness in a robotic picker can tangle up the whole shed’s operations and delay thousands of deliveries.

But as delivery schedules have dwindled into hours, even the gigantic warehouse full of stuff in a central place such as the triangle is proving insufficient. Now, companies also need smaller distribution centres around the country, to respond rapidly to orders and to abbreviate the last mile as much as possible. These smaller sheds cannot stock as much, but the foresight of data analytics now makes a keen strategic efficiency possible. Woodbridge remembers how, while visiting a shipping provider’s facility a few years ago, he saw a curious pile of Amazon parcels.

“I said: ‘They haven’t got any names on them. Who are they for?’” he told me. The packages held video games, it turned out: the newest edition of the annual Fifa series by Electronic Arts. “And they said: ‘Amazon knows, if you’ve bought the game for the last three years or whatever, that you’re likely to buy it again.’ So they’ve already got it packaged up for you, waiting for you to press the button. You do that, and they’ll stick your name on it, and it’s gone.”

How our home delivery habit reshaped the world (The Guardian)

Image: AP S/Alamy

Wednesday, November 20, 2019

No One Likes the Real Me!

Hi Polly,

I desperately need some practical advice about a very impractical life problem. That problem being, I don’t care about my life. To be clear, I don’t want to stop living, and my life could probably be worse. But every day, I think about the things I need to do in order to succeed in college and build a career, and though I try as hard as I can, I just do not care. It’s like pulling teeth to get myself to study or to apply for jobs or to network with people, because I have to fight through the voice in my head screaming that this stuff doesn’t matter.

My real problem is, I start thinking about what could even come after college, and my whole mind goes blank. My degree in communications may eventually get me a better job, but due to my utter lack of charisma and drive, it may not. You know the saying, “It takes a village”? Well, I agree. No one gets anywhere without the support of other people. But in order for people to support you, they need to like you, and I’m not very likable. It’s really hard for me to connect with others on a genuine level. I love my parents, but due to differences in religion, sexuality, and life goals, we tend to keep our conversations light both in content and in frequency. When I make friends, they usually decide I’m not what they signed up for and leave, or I ask too much of them and drive them away. Dating has been a similar disaster. I was okay at peer tutoring, and I was okay at retail, but at a certain point, I just couldn’t turn on whatever it is you turn on to make people feel like the interaction was worthwhile.

It’s not that I hate other people, or that I can’t talk to them. It’s just that it feels terrible the whole time.

I am not prepared for a world of constant communication, of marketing myself. And the older I get, the more I see that I’ll never escape the need to be something more palatable in order to be supported emotionally, and also in order to get hired and continue eating. I’m not trying to be a bitch. I really, truly believe in love and friendship and the power of human connection. But I also really, truly have to make people like me so I can pay my rent. And I have proof that people don’t like my natural personality. So here I am trying to find meaning in a world that, as a whole, doesn’t like the introverted overthinker, the too-honest but also too-distant person that I really am — and also doesn’t really like the person I try to be for its benefit. There is no way for me to win, no matter what job I have or what classes I take or what I do with my life.

Do you have any tips for dealing with a world like this? Because I’m absolutely exhausted.

I Want to Be Me (But I Want to Eat)

Dear IWTBM,

Cultivate your faith in the world. There is love for you here.

Yes, plenty of people dislike introverted overthinkers who are too honest and also too distant. The worst possible thing that someone like that can do, though, is pretend to be an upbeat extrovert for the sake of others. Introverted overthinkers with confessional impulses have to learn to love and accept who they are. Then they can be themselves and other people will enjoy them, embrace them, envy their honesty, admire their ideas, adore their unique perspectives, and savor their company.

Right now, you’re taking your stressful circumstances (working your way through college) and your very sensitive, alienated perspective on the world (everyone is predictable and bubbly and abhors complexity) and you’re bundling them together into a dreary outlook for your future. But you don’t even know what life after college will be like. Life in a college town among college students, working a menial job, does not offer an accurate snapshot of life anywhere else. I grew up in a college town and I’ve worked many, many menial jobs. Extrapolating from this habitat is a big mistake. Keep your mind open, because the world is much more wild and interesting than you can imagine.

I say this all the time, and I never stop believing it: Unless you’re naturally a sociopath or predator, you can be yourself around other people — even people who are different from you — and many of them will love you for it. The ones who don’t aren’t some bellwether of your success as a human being. Cast them aside and sally forth with an open heart.

Your primary problem right now is your firm belief that people hate your “natural” personality. You are certain, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that you’re broken and unlovable and you have to hide the truth about who you are. Many people believe this at your age. Some of the people who seem to be rejecting you also believe this about themselves. Instead of fixating on what you’re doing wrong in every interaction, use your sensitive nature to be still and tune into how insecure and ashamed the people around you are. Observe the jittery robots in your midst. Half of the people you encounter as extroverted are secretly introverts. Half of the people you experience as confident are massively insecure. Look for a reflection of your natural, too honest, too distant self hiding behind their masks. It’s there.

It feels terrible to talk to people because you’re trying to make them like you. The second you remove that imperative from your mind, things will improve. You say people don’t like your “natural” personality, but has anyone really experienced it? As long as you’re anxious over how much people like you, trust me, your natural personality is still hidden. The only way your real personality will show is if you connect with other people without fear.

In order to get there, you have to do a bunch of tough things at once. You have to stop obsessing about what people think of you. You have to stop trying so hard to impress people. You have to stop overexplaining everything you do to other people. You have to lower your expectations of others. You have to accept people for who they are (giving them the acceptance that you don’t give yourself yet). You have to listen closely to others instead of remaining preoccupied with how you’re coming across. And you have to speak honestly about your goals, desires, challenges, and flaws.

To someone who’s been trying too hard for years, that probably sounds like an enormous amount of work. But you can also take a short cut: Stop trying to impress people, full stop. Let go of your narrative that you’re unlikable. Let go of the false belief that you’ll only make friends and make a living if you bullshit people. Abandon this notion that no one has ever liked you. You are coating the world in darkness, out of fear and stress and loneliness. Try a new path forward instead. (...)

What people dislike about you, once they become your friend, is not your natural self. What they dislike is how hard you work, and how much compensatory devotion you expect from them, prematurely, and how angry and rejected you feel when someone lets you down, and how determined you are to hide your true self, even as you demand that other people show their true selves. No matter who you are naturally, as long as you’re pissed off and you’re trying too hard and you’re also fearful and sad and half-hiding, people won’t like you. Even if you think you’re playing the part of the enthusiastic, fun, thoroughly chill new friend convincingly, most people see through it. High-strung people can’t hide themselves that easily — a fact that, once we start to notice it, makes us even more high-strung, and even more convinced that there’s something deeply wrong with us.

by Heather Havrilesky, The Cut | Read more:

Image: SG Wildlife Photography / 500px/Getty Images/500px PlusDisney Says It Raised Park Ticket Prices to Improve Your Experience

The successful launch of the Disney+ streaming service has been getting a lot of attention and boosting the Walt Disney Company’s stock price, but that’s not the only bright spot in the company’s recent performance. When Disney announced quarterly earnings two weeks ago, it said its “parks, products and experiences” segment generated 8 percent more revenue and 17 percent more operating income in this year’s third calendar quarter than in the same quarter a year earlier.

How did the company make more money at its theme parks? Mostly by raising prices. But Disney says it’s for your own good.

Until 2016, Disney park ticket prices were the same every day, but now prices are tiered based on they day you visit into “value,” “regular,” and “peak.” The company frames this as a matter of “yield management” — using low prices to push guests to visit on off-season Tuesdays and high prices to make the parks less oppressively crowded on summer Saturdays — but in practice, Disneyland’s base ticket price on “value” days ($104) is sharply higher than the any-day ticket price just a few years ago ($87 in 2012). Plus, there were only 47 value-price days in 2019 and the last one was May 23, so for the rest of the year, if you’re over the age of 9, you won’t be getting into Disneyland for less than $129. On peak days, that will be $149.

These high prices are one factor that has suppressed crowds, at least at Disneyland in California. Back in July, the Orange County Register reported on an “apparent scarcity of visitors” that made this summer “the best time to visit Disneyland.” That seems to be holding true in the fall: I visited Disneyland on Tuesday; my one-day park ticket was a whopping $194, and, true to Disney executives’ claims, my guest experience was indeed enhanced by what appeared to be relatively limited crowds.

The base ticket price on Tuesday was $129, so how did I end up paying $194? Because I paid $50 for the privilege of visiting both Disneyland Park and Disney California Adventure on the same ticket, and another $15 for MaxPass, a feature that allowed me to make ride reservations through the Disneyland smartphone app. Tuesday was not a “peak” day; if I visited again this Saturday, the same ticket package would cost me $214.

But for this high price, I did get an experience that was a lot more seamless with a lot less waiting than I remember from Disney parks in my childhood, and not just because of relatively light crowds. The MaxPass offering meant my friends and I could take out our phones at noon, standing inside the new, Star Wars–themed Galaxy’s Edge area at Disneyland Park, and make a reservation for a 6:30 p.m. ride on Radiator Springs Racers, the Cars-themed attraction that draws the biggest crowds at California Adventure, about a half-mile away. When we got to Radiator Springs hours later, after many intervening rides and a few cocktails, we waited less than ten minutes to board, even as the standby rider line (for those without reservations) had a posted waiting time of 80 minutes.

If we hadn’t bought the add-ons, we wouldn’t have been able to get to all the rides we wanted to in a single day, and we would have spent a lot more time waiting in lines and shuffling around to obtain FastPass reservation tickets. And of course, if ticket prices had stayed lower, the lines might have been longer everywhere — as it stood, we were able to walk onto Space Mountain (recently rechristened Hyperspace Mountain) around 11 a.m. with no reservation and a less-than 20-minute wait.

Disney has not gone as far as its competitors in letting customers pay to avoid waiting. Unlike at Six Flags, which has tiered ticket pricing, where the more you pay the less you wait, Disney would not be so gauche as to use such an in-your-face system to rank guest importance. All guests at Disney parks are special, and therefore all guests are welcome to use the FastPass system to reserve a limited number of rides in advance and come back when it’s their turn without waiting in line.

But there are subtler ways Disney gives advantages to customers it values more: Paying for MaxPass makes it easier to use FastPass more effectively, because you can use a phone app instead of visiting physical reservation kiosks; on certain days, paying Disney hotel guests can enter the parks before they open to the public and stay after they close; in Florida, hotel guests can make ride reservations far in advance of their vacations; and for hundreds of dollars an hour, you even can hire a VIP guide to escort your family to the front of the line. And the main way Disney has been stratifying its guests is an invisible one: By raising ticket prices, it is keeping some potential guests out of the parks altogether.

by Josh Barro, The Intelligencer | Read more:

Image: Salvatore Romano/NurPhoto via Getty ImagesSecretive Energy Startup Achieves Solar Breakthrough

A secretive startup backed by Bill Gates has achieved a solar breakthrough aimed at saving the planet.

Heliogen, a clean energy company that emerged from stealth mode on Tuesday, said it has discovered a way to use artificial intelligence and a field of mirrors to reflect so much sunlight that it generates extreme heat above 1,000 degrees Celsius.

Essentially, Heliogen created a solar oven — one capable of reaching temperatures that are roughly a quarter of what you'd find on the surface of the sun.

The breakthrough means that, for the first time, concentrated solar energy can be used to create the extreme heat required to make cement, steel, glass and other industrial processes. In other words, carbon-free sunlight can replace fossil fuels in a heavy carbon-emitting corner of the economy that has been untouched by the clean energy revolution.

The breakthrough means that, for the first time, concentrated solar energy can be used to create the extreme heat required to make cement, steel, glass and other industrial processes. In other words, carbon-free sunlight can replace fossil fuels in a heavy carbon-emitting corner of the economy that has been untouched by the clean energy revolution.

"We are rolling out technology that can beat the price of fossil fuels and also not make the CO2 emissions," Bill Gross, Heliogen's founder and CEO, told CNN Business. "And that's really the holy grail."

Heliogen, which is also backed by billionaire Los Angeles Times owner Patrick Soon-Shiong, believes the patented technology will be able to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions from industry. Cement, for example, accounts for 7% of global CO2 emissions, according to the International Energy Agency.

"Bill and the team have truly now harnessed the sun," Soon-Shiong, who also sits on the Heliogen board, told CNN Business. "The potential to humankind is enormous. ... The potential to business is unfathomable." (...)

Heliogen uses computer vision software, automatic edge detection and other sophisticated technology to train a field of mirrors to reflect solar beams to one single spot.

"If you take a thousand mirrors and have them align exactly to a single point, you can achieve extremely, extremely high temperatures," Gross said, who added that Heliogen made its breakthrough on the first day it turned its plant on.

Heliogen said it is generating so much heat that its technology could eventually be used to create clean hydrogen at scale. That carbon-free hydrogen could then be turned into a fuel for trucks and airplanes.

"If you can make hydrogen that's green, that's a gamechanger," said Gross. "Long term, we want to be the green hydrogen company."

by Matt Egan, CNN Business | Read more:

Image: Heliogen

[ed. Perhaps other (less laudable) uses as well. See also: Company claims breakthrough in concentrating the Sun’s rays (Ars Technica); and, per the law of unintended consequences: From the Walkie Talkie to the Death Ray Hotel (Guardian). Update: A Solar 'Breakthrough' Won't Solve Cement's Carbon Problem (Wired).]

Heliogen, a clean energy company that emerged from stealth mode on Tuesday, said it has discovered a way to use artificial intelligence and a field of mirrors to reflect so much sunlight that it generates extreme heat above 1,000 degrees Celsius.

Essentially, Heliogen created a solar oven — one capable of reaching temperatures that are roughly a quarter of what you'd find on the surface of the sun.

The breakthrough means that, for the first time, concentrated solar energy can be used to create the extreme heat required to make cement, steel, glass and other industrial processes. In other words, carbon-free sunlight can replace fossil fuels in a heavy carbon-emitting corner of the economy that has been untouched by the clean energy revolution.

The breakthrough means that, for the first time, concentrated solar energy can be used to create the extreme heat required to make cement, steel, glass and other industrial processes. In other words, carbon-free sunlight can replace fossil fuels in a heavy carbon-emitting corner of the economy that has been untouched by the clean energy revolution."We are rolling out technology that can beat the price of fossil fuels and also not make the CO2 emissions," Bill Gross, Heliogen's founder and CEO, told CNN Business. "And that's really the holy grail."

Heliogen, which is also backed by billionaire Los Angeles Times owner Patrick Soon-Shiong, believes the patented technology will be able to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions from industry. Cement, for example, accounts for 7% of global CO2 emissions, according to the International Energy Agency.

"Bill and the team have truly now harnessed the sun," Soon-Shiong, who also sits on the Heliogen board, told CNN Business. "The potential to humankind is enormous. ... The potential to business is unfathomable." (...)

Heliogen uses computer vision software, automatic edge detection and other sophisticated technology to train a field of mirrors to reflect solar beams to one single spot.

"If you take a thousand mirrors and have them align exactly to a single point, you can achieve extremely, extremely high temperatures," Gross said, who added that Heliogen made its breakthrough on the first day it turned its plant on.

Heliogen said it is generating so much heat that its technology could eventually be used to create clean hydrogen at scale. That carbon-free hydrogen could then be turned into a fuel for trucks and airplanes.

"If you can make hydrogen that's green, that's a gamechanger," said Gross. "Long term, we want to be the green hydrogen company."

by Matt Egan, CNN Business | Read more:

Image: Heliogen

[ed. Perhaps other (less laudable) uses as well. See also: Company claims breakthrough in concentrating the Sun’s rays (Ars Technica); and, per the law of unintended consequences: From the Walkie Talkie to the Death Ray Hotel (Guardian). Update: A Solar 'Breakthrough' Won't Solve Cement's Carbon Problem (Wired).]

The Crying Game

I suppose some people can weep softly and become more beautiful, but after a real cry, most people are hideous, as if they’ve grown a spare and diseased face beneath the one you know, leaving very little room for the eyes. Or they look as if they’ve been beaten. We look. I look. Once, in fifth grade, I cried at school for a reason I cannot recall, and afterward a popular boy—rattail, skateboard—told me I looked like a druggie, and I was so pleased to be seen I made him repeat it.

•••

Ovid would prefer that I and other women restrain ourselves:

The length of the cry matters. I especially value an extended session, which gives me time to become curious, to look in the mirror, to observe my physical sadness. A truly powerful cry can withstand even this scientific activity. You lurch toward the bathroom, head hunched over, tucked in, and then gather your nerve to lift your gaze toward the mirror, where you see your hiccoughing breath shake your shoulders, your nose like a lifelong drunk’s. It may interest you for a while to touch your swollen face, to peer into one bloodshot eye and another, but the beauty’s really in the movement, in watching your mouth try to swallow despair. It is not easy, after looking, to convince the crying you mean it no harm, but with quiet and with patience—you are Jane Goodall with the chimpanzees—the crying will slowly get used to you. It will return.

•••

To cry or not to cry is sometimes a choice, and no telling which is the better. Not true—if you are alone, or with only one other, cry. To cry with more people present, concludes the International Study of Adult Crying, can lead to a worsening mood, though that may depend on others’ reactions. You can be made to feel ashamed. Most frequently criers report others responding with compassion, or what the study categorizes as “comfort words, comfort arms, and understanding.” If you are alone, comfort arms are still available; you hold yourself together.

•••

It is fortunate to have a nose. Hard to feel you are too tragic a figure when the tears mix with snot. There is no glamour in honking.

•••

Once I was unexpectedly dumped in public. A campus parking lot one afternoon. I put all my crying into my mouth, felt it shake while I stalked to the car, inside which I let the crying move north to my eyes and south to my heaving gut. The car is a private crying area. If you see a person crying near a car, you may need to offer help. If you see a person crying inside a car, you know they are already held.

by Heather Christle, Bookforum | Read more:

•••

Ovid would prefer that I and other women restrain ourselves:

There is no limit to art: in weeping, you need to•••

be comely,

Learn how to turn on the tears still keeping

proper control.

The length of the cry matters. I especially value an extended session, which gives me time to become curious, to look in the mirror, to observe my physical sadness. A truly powerful cry can withstand even this scientific activity. You lurch toward the bathroom, head hunched over, tucked in, and then gather your nerve to lift your gaze toward the mirror, where you see your hiccoughing breath shake your shoulders, your nose like a lifelong drunk’s. It may interest you for a while to touch your swollen face, to peer into one bloodshot eye and another, but the beauty’s really in the movement, in watching your mouth try to swallow despair. It is not easy, after looking, to convince the crying you mean it no harm, but with quiet and with patience—you are Jane Goodall with the chimpanzees—the crying will slowly get used to you. It will return.

•••

To cry or not to cry is sometimes a choice, and no telling which is the better. Not true—if you are alone, or with only one other, cry. To cry with more people present, concludes the International Study of Adult Crying, can lead to a worsening mood, though that may depend on others’ reactions. You can be made to feel ashamed. Most frequently criers report others responding with compassion, or what the study categorizes as “comfort words, comfort arms, and understanding.” If you are alone, comfort arms are still available; you hold yourself together.

•••

It is fortunate to have a nose. Hard to feel you are too tragic a figure when the tears mix with snot. There is no glamour in honking.

•••

Once I was unexpectedly dumped in public. A campus parking lot one afternoon. I put all my crying into my mouth, felt it shake while I stalked to the car, inside which I let the crying move north to my eyes and south to my heaving gut. The car is a private crying area. If you see a person crying near a car, you may need to offer help. If you see a person crying inside a car, you know they are already held.

by Heather Christle, Bookforum | Read more:

Tuesday, November 19, 2019

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)