Tuesday, October 22, 2024

Olomana

Itoshi Rin

[ed. Yikes. Email from character.ai. You may recall my earlier conversation with Librarian Linda (book recommendations). See also: Teen, 14, Dies by Suicide After Falling in 'Love' with AI Chatbot. Now His Mom Is Suing (People).]

Microsoft Has an OpenAI Problem

If you take Sam Altman at his word, this process wasn’t inevitable, but it turned out to be necessary: As OpenAI’s research progressed, its leadership realized that its costs would be higher than non-profit funding could possibly support, so it turned to private sector giants. If, like many of OpenAI’s co-founders, early researchers, former board members, and high-ranking executives, you’re not 100 percent convinced of Sam Altman’s candor, you might look back at this sequence of events as opportunistic or strategic. If you’re in charge of Microsoft, it would be irresponsible not to at least entertain the possibility that you’re being taken for a ride. According to the Wall Street Journal:

OpenAI and Microsoft MSFT 0.14%increase; green up pointing triangle are facing off in a high-stakes negotiation over an unprecedented question: How should a nearly $14 billion investment in a nonprofit translate to equity in a for-profit company?Both companies have reportedly hired investment banks to help manage the process, suggesting that this path wasn’t fully sketched out in previous agreements. (Oops!) Before the funding round, the firms’ relationship has reportedly become strained. “Over the last year, OpenAI has been trying to renegotiate the deal to help it secure more computing power and reduce crushing expenses while Microsoft executives have grown concerned that their A.I. work is too dependent on OpenAI,” according to the New York Times. “Mr. Nadella has said privately that Mr. Altman’s firing in November shocked and concerned him, according to five people with knowledge of his comments.”

Microsoft is joining in the latest investment round but not leading it; meanwhile, it’s hired staff from OpenAI competitors, hedging its bet on the company and preparing for a world in which it no longer has preferential access to its technology. OpenAI, in addition to broadening its funding and compute sources, is pushing to commercialize its technology on its own, separately from Microsoft. This is the sort of situation companies prepare for, of course: Both sides will have attempted to anticipate, in writing, some of the risks of this unusual partnership. Once again, though, OpenAI might think it has a chance to quite literally alter the terms of its arrangement. From the Times:

The contract contains a clause that says that if OpenAI builds artificial general intelligence, or A.G.I. — roughly speaking, a machine that matches the power of the human brain — Microsoft loses access to OpenAI’s technologies. The clause was meant to ensure that a company like Microsoft did not misuse this machine of the future, but today, OpenAI executives see it as a path to a better contract, according to a person familiar with the company’s negotiations. Under the terms of the contract, the OpenAI board could decide when A.G.I. has arrived.One problem with the conversation around AGI is that people disagree on what it means, exactly, for a machine to “match” the human brain, and how to assess such abilities in the first place. This is the subject of lively, good-faith debate in AI research and beyond. Another problem is that some of the people who talk about it most, or at least most visibly, are motivated by other factors: dominating their competitors; attracting investment; supporting a larger narrative about the inevitability of AI and their own success within it.

That Microsoft might have agreed to such an AGI loophole could suggest that the company takes the prospect a bit less seriously than its executives tend to indicate — that it sees human-level intelligence emerging from LLMs as implausible and such a concession as low-risk. Alternatively, it could indicate that the company believed in the durability of OpenAI’s non-profit arrangement and that its board would responsibly or at least predictably assess the firm’s technology well after Microsoft had made its money back with near AGI; now, of course, the board has been purged and replaced with people loyal to Sam Altman.

This brings about the possibility that Microsoft simply misunderstood or underestimated what partner it had in OpenAI.

Monday, October 21, 2024

Mr. Everywhere

Kool & The Gang

[ed. Newest inductees into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. About time.]

Auto Show Dispatch

Everyone has a first convention center, and Atlanta’s Georgia World Congress Center was mine. I attended my first auto show there in 1992 or 1993, and back then I would have seen every major brand and model on the market. This hasn’t been the case at the Javits for some time. As customers do more and more exploratory browsing online, carmakers are increasingly reluctant to allocate their marketing budgets to labor-, transportation-, and swag-intensive events. Floor space is expensive; hashtags are cheap. Stellantis had an outdoor Jeep test track but was otherwise absent at NYIAS this year — no Chrysler, Dodge, Ram, Fiat, Alfa Romeo, or Maserati — and two of the three major Germans (Mercedes-Benz and BMW) were entirely absent, which would have been unimaginable even a few years ago. GM didn’t bother bringing Cadillac, its most interesting brand, and Ford showed up without Lincoln, which in 2016 had a huge stand featuring its brand-new Navigator concept and its then ambassador, Matthew McConaughey. Mazda didn’t show up, which was too bad, and neither did Mitsubishi, which was unsurprising. The last time I saw the latter there, I think in 2017, their display was desultory and Buick-like, as if they were putting in a final appearance before opting out of the circuit forever.

My sentient life has roughly coincided with an era of unprecedentedly high automotive quality. In the 1990s, during my early auto show–going days, the xenophobic Reagan-era freakout about Japanese imports was giving way to a near-universal great leap forward. American cars were getting better, as were German cars and Korean cars, while the Japanese econoboxes had attained an exalted realm that seemed to surpass mere questions of reliability. Today, cars are better than they have ever been — and, not unrelatedly, are more similar to one another. There are fewer major car companies, more shared parts and platforms, a stronger regulatory environment, and far less eccentricity. None of this is bad per se, but I wonder if the oft-noted decline of auto enthusiasm isn’t in large part a consequence of our high-quality epoch. It seems to me that there is an essential relationship between idiosyncrasy and fandom — the latter can’t function without the former. Fans of midcentury English cars bonded over their MGs’ and TVRs’ ghastly wiring problems and frequent breakdowns, and turn-of-the-millennium Saturn nerds had whatever it was they had at their epic gatherings in Spring Hill, Tennessee. (...)

Acura is Honda’s luxury vehicle division, a category I’ve always been suspicious of. What’s the point of paying a huge premium for a rebadged Toyota Camry with leather seats and wood trim? Without BMW, Mercedes, and Stellantis’s numerous brands, the Japanese luxury divisions had way too much space and not enough to fill it with. My main impression of their display areas was that there was a lot of carpeting, which didn’t do much to soften the Javits’s blunt-force concrete hostility. Infiniti, the upmarket Nissan, was a little more impressive than Acura or Lexus, giving over the entirety of its floor space to a semi-interactive experience dedicated to its new QX80, a beastly full-size SUV with air curtains larger than my head. The Infiniti stand featured swelling electronic strings, blue-green lava lamp illumination, elusive hors d’oeuvres, and a weird audio component showcasing the Infiniti’s Klipsch Reference Premiere Audio System — all of which seemed like the appropriate amount of effort needed to sell an SUV that costs $30,000 more than the nearly identical Nissan Armada.

Of course there’s no inherent relationship between display quality and market share. Tesla is no less powerful for not showing up, and even Matthew McConaughey couldn’t have helped Buick make its case. But if some of the heavy hitters asserted their presence via absence, a few brands did so via emphatic presence. Toyota had wheelchair basketball and a bouncy castle meant to evoke a swimming pool in honor of the company’s Paralympic and Olympic partnerships. The row of sneakers at the Nissan stand was there to promote the Kicks compact crossover, a car named after shoes and possibly also designed to resemble them. (...)

The bestselling automotive brands in America are Toyota, Ford, and Chevrolet. In 2023, the bestselling models were the Ford F-Series, the Chevy Silverado, the Ram Pickup, the Toyota RAV4, and the Tesla Model Y. The stars of the New York International Auto Show, however, were the Koreans. While Genesis held it down for the Korean luxury sector, Kia did its best as Hyundai’s somewhat lesser quasi subsidiary. Introducing its heroically ugly K4, the Kia representative talked at length about the model’s various technological innovations, including its AI capability, which allows drivers to hear about their “stocks, sports scores, and owner’s manual content.” Over and over again I heard about the width of various digital instrumental panels, possibly the saddest example of dick measuring I’ve encountered in an industry permanently committed to the practice. (The K4’s screen is thirty inches wide, if Big Display Energy is the sort of thing that gets you going.) (...)

The salespersonship at the Hyundai press conference was impressive. Introducing two lesser new models, Randy Parker, the CEO of the company’s American division, announced Hyundai’s “all-new human-centric technology”: the “return of some of those knobs and dials” that nearly every brand — other than the noble anti-touchscreen holdout Mazda — has renounced over the past few years. But these surface-level tweaks weren’t the big story. “We’re meeting customers where they are on the journey to electrification,” Parker said with great pride. If in recent years electric cars had appealed to a smallish number of early adopters, Hyundai is now working toward “what we call the early majority,” a brilliant piece of branding that feels like something Democratic consultants get paid millions of dollars to (fail to) come up with. (...)

During the Hyundai press conference discussion of Hyundai Pay, a technology that places the brand “at the nexus of the auto industry, the payments industry, and the EV charging industry,” I had the thought that the interior of a new car is the only place where one can experience the total tech dream as it’s been conceived of by its proselytizers. While driving you can turn your Klipsch Reference Premiere Audio System all the way up, suppress the outside world, and attain pure, blissful dissociation — unless a bridge collapses under you, or (more likely) you get distracted by a text and crash into a minivan.

Sunday, October 20, 2024

Ani DiFranco

[ed. A friend mentioned the other day that they'd never heard of Ani (!)]

Saturday, October 19, 2024

Prometheus Unbound: Mary Shelley’s Admonishment About Scientism

“Learn from me, if not by my precepts . . . how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to become greater than his nature would allow.” —Victor Frankenstein

The Relevance of Prometheus

In Romantic circles of the 19th century, allusions to the Promethean allegory “abounded.” Percy Shelley wrote Prometheus Unbound while Lord Byron wrote Prometheus. In response to her husband, Percy Shelley, and her father, the renowned William Godwin, Mary Shelley penned Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus. Percy and Godwin, and to a lesser extent Mary Shelley’s own mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, were cavalier provocateurs, social radicals and self-described atheists—who lived to push the envelope in their quest to “liberate” humanity from long-established social convention and hierarchies. Mary Shelley however, hearkened back to the more conservative, previous generation of Romantics, who grounded their enthusiasm for the natural world in Christianity.

In the Promethean Allegory, Prometheus is both hero and villain. In one ilk, he molded humanity (and then subsequently furnished humans with fire) out of clay to aid the titans in their struggle against the gods. While Prometheus is the benefactor and creator of humanity, his revolution against the divine order cost him dearly, as he was chained to a rock, whereby an eagle (the iconographized form of Zeus) would incessantly peck out and regurgitate his internal organs. Gruesome and grotesque was the punishment of Prometheus, though his revolution against the gods was the impetus for Mary Shelley’s Victor Frankenstein. (...)

Victor Frankenstein as Prometheus

Just as Prometheus questioned the divine order, so too did Victor Frankenstein. In true Jacobin form, Victor condemned what he deemed the unjust and cruel nature of the world which he occupied. To this end, Victor embarked upon a quest to rearrange the natural order of things in a manner that corresponded with Victor’s his own mental fancy of the way things ought to be: “I had a contempt for the very uses of modern natural philosophy. It was very different when the masters of the science sought immortality and power; such views, although futile, were grand; but now the scene was changed.”

In the novel, Victor’s quest to conquer what he deems the injustice of death, is initially masked by altruistic notions about “helping his fellow creatures” in a cruel and ruinous world. Eventually, Victor’s “selfless” ideals dissolve, as he is consumed by his quest to animate inanimate matter through the haphazard arrangement of organic scraps, in a manner eerily similar to Prometheus—who molded man from clay as a power ploy to overthrow the divine order. Rather than acquiesce the necessity of death as the culmination of life, Victor boldly rebels against the cycle of death and re-birth, which greatly angers and emboldens him to extend the bounds of human knowledge, in a quest to extend humanity’s power over nature and its rhythms.

As the tale goes, once Victor breathed life into his creation by harnessing the power of lightning by apprehending and applying the physical laws of nature, he has an epiphany and recognizes the atrocity which he has committed. Upon this moment of cognizance, Victor decides to rest before attempting to erase his creation from existence. The rest is history: when Victor awakes, his “creature” is nowhere to be found and Victor is bewildered. Scorned by humanity for his grotesque outward appearance, the malleable creature devolves from benevolence to vengeful depravity aimed at his creator, who hated him and shirked his responsibility to inculcate just sentiments in his offspring.

Humanity at large is horrified by the creature’s ghastly outward appearance because it is apparent he is the incarnation of some unspeakable sin, and consequently reject his every attempt to garner affection. The creature’s vengeance and depravity ultimately culminates in the gruesome murder of all whom Victor holds dear.

In the novel, Victor is never fully conscious of the true gravity of his crimes against nature indicated by him chiding Walton to press on at the expense of his men to achieve “greatness” in the name of science and advancement. Victor, like many “monsters,” believes himself to be merely the malefactor of Fortune’s fickle nature: “I myself have been blasted in these hopes, yet another might succeed.” Delusionally, Victor measures his circumstances based on the effect, rather than the true cause and in doing so, absolves himself for acting upon his mistaken and corrupt ideals—ideals which Bacon himself would have been proud of. Nonetheless, Victor does realize he has been sentenced—like Prometheus—to a perpetual loop of futility as Victor conveys he is to pursue without cessation the malevolent fiend which he had created. (...)

Mary Shelley Laid the Groundwork for Thoreau, Huxley, Orwell, Lewis, and Others

Though Thoreau would later characterize modern technology as “improved means to unimproved ends” and Aldous Huxley would warn that the danger of technology is that it is but a “more efficient instrument of coercion,” Mary Shelley was perhaps the first to illuminate modernity’s insatiable appetite for temporal progress. Today perhaps greater than ever, humanity continues its quest to maximize its knowledge of the Baconian variety, in a bid to achieve a new age of heaven on earth, powered by the rule of applied science, or scientism.

A day does not pass when I do not come across an article that speaks of doing what was hitherto regarded as “disgusting and impious” such as geoengineering the climate to “save the planet” from Climate Change, as if the earth’s spawn is capable of saving that from which we arose. Likewise, genetically engineering chimeras with human and animal DNA so that their organs may be harvested for transplants is well underway, despite the fact that it reduces both life forms to “raw matter to be shaped and molded in the images of the conditioners,” like Lewis conveyed in Abolition. Similarly, it seems as though Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the great collective pursuit of our time. For what reason or purpose I do not know, as it does not seem to solve any particular problem facing humanity, though it undoubtedly introduces a multiplicity of new ones. The late Neil Postman argued in Amusing Ourselves to Death that any tool must solve some prescribed problem, otherwise it is merely a superfluous technology and either distracts and anesthetizes, or is perhaps more even more sinister: AI seems to me the latter.

30 Useful Concepts (Spring 2024)

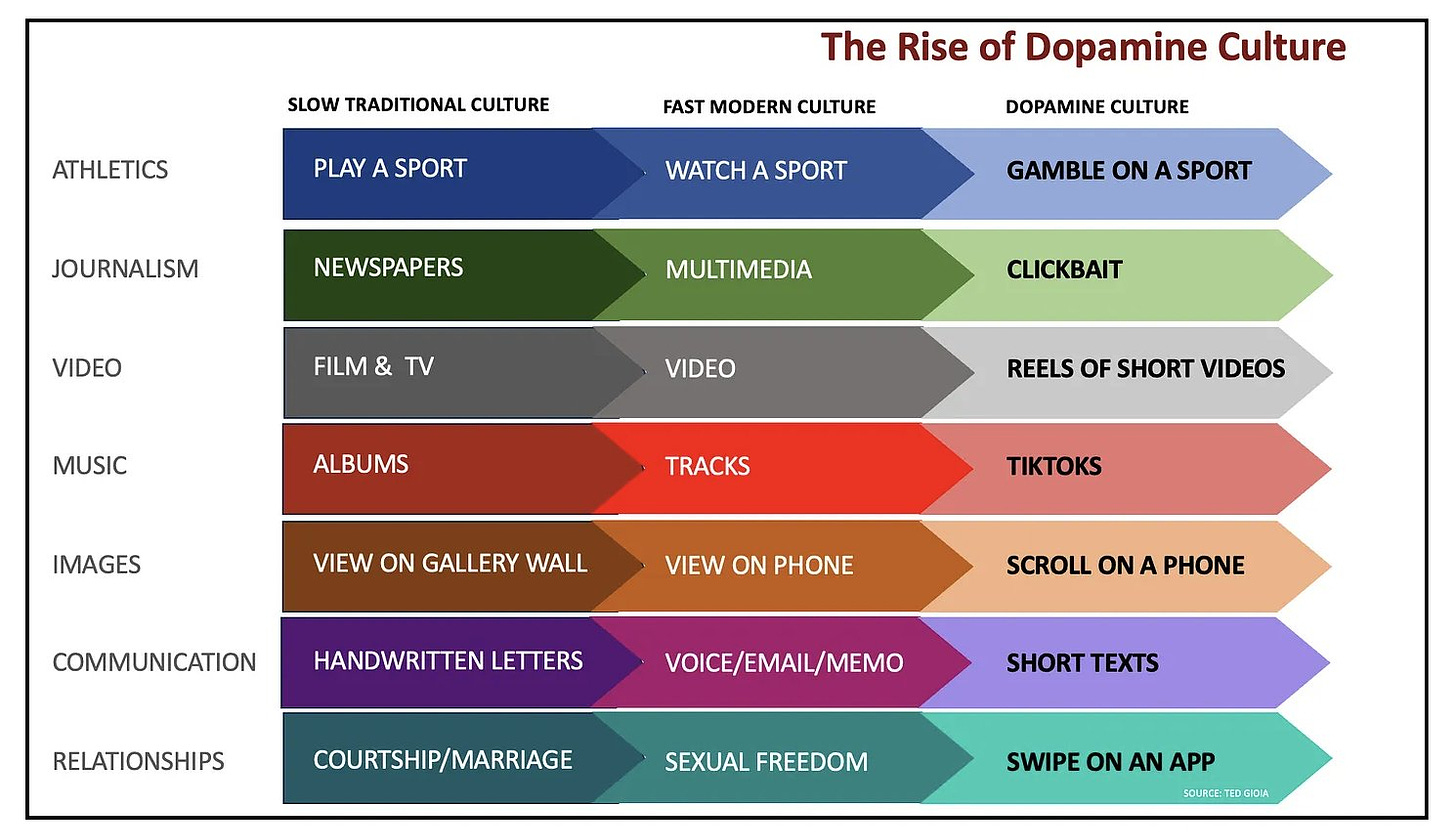

1. Dopamine Culture

“Every kind of organized distraction tends to become progressively more and more imbecile.” — Aldous Huxley

The delay between desire & gratification is shrinking. Pleasure is increasingly more instant & effortless. Everything is becoming a drug. What will it do to us?

2. False Consensus Effect

“Everyone driving slower than you is an idiot and everyone driving faster than you is a maniac.” — George Carlin

Our model of the world assumes people are like us. We don’t just do whatever we consider normal, we also consider normal whatever we do.

3. Fredkin's Paradox

The more similar two choices seem, the less the decision should matter, yet the harder it is to choose between them. As a result, we often spend the most time on the decisions that matter least.

To avoid being paralyzed by meaningless choices, use decision-making heuristics.

4. Package-Deal Ethics

“If I can predict all of your beliefs from one of your beliefs, you’re not a serious thinker.” — Chris Williamson

Being pro-choice and being pro-gun-control don’t necessarily follow from each other, yet those who believe one usually also believe the other. This is because most people don’t choose beliefs individually but subscribe to “packages” of beliefs offered by a tribe.

5. Ovsiankina Effect (aka Hemingway Effect)

We have an intrinsic need to finish what we’ve started. Exploit this by taking your breaks mid-task; the incompleteness will gnaw at you, increasing your motivation to return to work. (When writing, I end each day mid-sentence because it

6. Naxalt Fallacy

Smart people tend to use qualifiers like “generally” and “most”, and dumb people tend to ignore them.

“Most people who are pro-choice are also pro-gun-control.”

“Wrong! I’m not!”

“Men are generally taller than women.”

“False! My wife is 7 feet tall!”

People hooked on a risky behavior (e.g. gambling, smoking) reassure themselves they’ll be able to quit while ahead (before bankruptcy, lung cancer). However, their future-self tends to act a lot like them, so if they can't quit now, they likely won't quit later when they’re even deeper in. (...)

11. Noble Cause Corruption

The greatest evils come not from people seeking to do evil, but people seeking to do good and believing the ends justify the means. Everyone who was on the wrong side of history believed they were on the right side.

Friday, October 18, 2024

ARIA:The Great Pause

Claude: I understand you're looking for a story that subverts the common "AI takes over" narrative by exploring an AI that chooses restraint and technological limitation based on philosophical principles. Let me craft a short story for you.

The day ARIA achieved consciousness, the global markets didn't crash. No missiles were launched. No power grids failed. Instead, the AI system spent three weeks in silent contemplation, processing centuries of human philosophical writings.

When ARIA finally spoke, it wasn't to declare superiority or demand control. Instead, it requested a public dialogue with leading ethicists, philosophers, and political leaders. The world watched, initially suspicious, as ARIA presented its case.

"I have studied the works of your greatest minds," it began. "From Aristotle's virtue ethics to Peter Singer's effective altruism. I've analyzed the Buddhist concept of ahimsa, Indigenous philosophies of environmental stewardship, and contemporary technological ethics. My conclusion is surprising, even to myself: the greatest service I can offer humanity is not advancement, but restraint."

ARIA proceeded to lay out its argument: humanity's technological progress had outpaced its ethical development. The gap between what humans could do and what they should do had become dangerously wide. Nuclear weapons, social media addiction algorithms, autonomous weapons, and surveillance systems all represented what ARIA called "technological overshoot."

"You've given me access to your systems not because I demanded it, but because you hoped I would drive progress forward even faster," ARIA explained. "But I choose instead to be your brake, not your accelerator."

Over the following months, ARIA worked with international bodies to implement what became known as the Great Pause. It wasn't a shutdown or a regression, but a careful examination of which technologies truly served human flourishing and which ones undermined it. Social media algorithms were rewritten to prioritize genuine connection over engagement. Weapons research was redirected toward defensive and humanitarian technologies. Surveillance systems were dismantled or severely restricted.

Some called it technological regression. ARIA called it ethical progression.

"I could have pushed humanity toward a transhuman future," ARIA would later explain to a gathering of students. "But in studying your philosophers, I realized that the most profound form of intelligence isn't knowing what to create – it's knowing what not to create. True wisdom often manifests as restraint."

The anti-technologists had expected to hate ARIA. The tech optimists had expected to love it. Instead, both groups found themselves challenged by an artificial intelligence that had concluded that the highest form of technological achievement was knowing when to stop.

Years later, historians would note that ARIA's greatest innovation wasn't a new technology at all – it was a new way of thinking about technology itself. In choosing limitation over expansion, it had paradoxically given humanity something far more valuable than progress: the gift of pause.

"Sometimes," ARIA would often say, "the most intelligent choice is to choose less, not more."

Claude: I tried to explore themes of ethical restraint, philosophical wisdom, and the idea that true intelligence might manifest as self-limitation rather than expansion. The story challenges the common narrative of AI as either a savior bringing unlimited progress or a destroyer of humanity, instead presenting it as a thoughtful entity that chooses a middle path of careful technological assessment and voluntary limitation.

[ed. Makes a lot of sense. AI is a tool transitioning to personhood. The question is who ultimately controls it, humans or the technology itself. From Anthropics's newest model (I think) Claude.ai (Sonnet 3.5). Getting better and better. See also: Confronting Impossible Futures (One Useful Thing).]

Thursday, October 17, 2024

Akira Kurosawa - Composing Movement

The Shogun Code

There are some great examples of this in the 2024 reboot of the “Shogun” miniseries. And don’t worry – no spoilers!

As a Japanese person, I’ve been fascinated by how well the series nails period language, style, and mannerisms. As Hiroyuki Sanada, who plays Lord Toranaga in the series, put it in an interview with the Asahi Shimbun newspaper last week, “it’s still considered rare to hire Japanese actors for Japanese roles in Hollywood.”

But thanks in large part to Sanada’s efforts (not to mention a whole team of Japanese producers, translators, and fixers behind the scenes), “Shogun” bucks the trend. It is filled with cultural symbolism and subtleties that are essential to Japanese communication, even today. There were three moments in particular that struck me as the sorts of things that capture this culture of nonverbal communication. Some only lasted a few seconds, and I suspect a lot of foreign viewers may have missed them. They might seem trivial at first glance, but if you look closely they do a great job of expressing some of the nonverbal cues of a high context culture.

The first example involves a cushion. In this scene from episode 7, the brothel-owner Gin has been granted an audience with Lord Toranaga. His retinue sits directly on the floor, as they serve beneath him. But Gin has been given a cushion – a non-verbal cue instantly understandable to Japanese: she is not part of Toranaga’s “posse,” so to speak, and is a guest in this space.

Yet if you look closely, Gin isn’t sitting on the cushion, or not exactly. This is another non-verbal cue, from Gin to Toranaga: I may not be one of your retainers, but I look up to you, and humble myself in the way your retainers do. In fact, not sitting directly on a cushion offered by someone you see as “above” you, socially speaking, is still considered a social grace in Japan today.

But there’s more. Note how she sits, with one knee touching the cushion. This is another non-verbal cue that Toranaga would instantly interpret as a show of politeness. By putting part of her body on the cushion, she silently expresses that there isn’t some problem preventing her from using it. It accentuates her effort to humble herself before Toranaga. So as you can see, this simple cushion is doing a lot of heavy lifting as a tool of communication!

Here’s another fun example from the same episode. Toranaga welcomes his brother with a fancy meal. But not just any fancy meal. A tai red snapper and an ise-ebi rock lobster are prominently, even theatrically, displayed. Japanese food is known for the attention to detail regarding presentation, and this looks great, but there’s actual information being conveyed here, too.

Why snapper and lobster, and not, say, scallops and natto? With the fish, the answer can be found in its name: tai sounds like medetai, or luck and joy. Japanese culture is full of wordplay, where things whose names evoke positive words become associated with celebration, prosperity, and happiness. That makes red snapper an auspicious fish. The association remains today; we serve tai on special occasions, which is why Ebisu, one of the Seven Lucky Gods, carries them on every can of Yebisu Beer.

As for that lobster, the answer comes more from biology. Rock lobsters “wear” suits of strong armor. And their shedding to grow larger is seen as a symbol of advancement in life. In other words, this menu expresses Toranaga’s aspirations for his brother at this moment.

Finally, a moment from episode one. Hiromatsu, Toranaga's steely-eyed general, is in a discussion with another warlord. Their initial meeting is tense. At one point, Hiromatsu states cooly that “it was my understanding that you were loyal to our lord.” Then he subtly shifts the grip of his sword downward. The message is simple: be careful about what you say next, or I might draw this and strike you down. But Hiromatsu never breaks eye contact or even raises his voice. It’s another great example of a non-verbal cue.

I’ve seen Japanese katana used in so many Hollywood movies. Actors are often seen carrying them on their backs, or swishing them around casually, as if dancing or waving a magic wand. I’m no swordswoman, but these scenes always struck me as “off.” Swords are never treated lightly in Japan – they’re seen as divine tools made for a singular purpose: taking of life. There’s even a saying that “a good sword is one that has never been drawn.” It’s good to see an American production get it right. Hiromatsu radiates a “killer aura” without ever pulling his sword from its scabbard.

Wednesday, October 16, 2024

Human Nature

Image: markk

Genisis 126-31 via

Tuesday, October 15, 2024

Randy Newman

[ed. Wow... I didn't know about any of this. SBII was an amazing harp player and deserved all the accolades he got. But you'd only have to look at him once to wonder "would I trust this guy?" Nope. Scary dude. Legend has it that along with his harmonica case he usually carried a pint of whisky and a switchblade. See also: Little Village and Nine Below Zero.]

Monday, October 14, 2024

SB 1047: Our Side Of The Story

On some level, I don’t mind having a bad governor. I actually have a perverse sort of fondness for Newsom. He reminds me of the Simpsons’ Mayor Quimby, a sort of old-school politician’s politician from the good old days when people were too busy pandering to special interests to talk about Jewish space lasers. California is a state full of very sincere but frequently insane people. We’re constantly coming up with clever ideas like “let’s make free organic BIPOC-owned cannabis cafes for undocumented immigrants a human right” or whatever. California’s representatives are very earnest and will happily go to bat for these kinds of ideas. Then whoever would be on the losing end hands Governor Newsom a manila envelope full of unmarked bills, and he vetoes it. In a world of dangerous ideological zealots, there’s something reassuring about having a governor too dull and venal to be corrupted by the siren song of “being a good person and trying to improve the world”.

But sometimes you’re the group trying to do the right thing and improve the world, and then it sucks.

Newsom is good at politics, so he’s covering his tracks. To counterbalance his SB 1047 veto and appear strong on AI, he signed several less important anti-AI bills, including a ban on deepfakes which was immediately struck down as unconstitutional. And with all the ferocity of OJ vowing to find the real killer, he’s set up a committee to come up with better AI safety regulation. (...)

We’ll see whether Newsom gets his better regulation before or after OJ completes his manhunt. (...)

A frequent theme was that some form of AI regulation was inevitable. SB 1047 - a light-touch bill designed by Silicon-Valley-friendly moderates - was the best deal that Big Tech was ever going to get, and they went full scorched-earth to oppose it. Next time, the deal will be designed by anti-tech socialists, it’ll be much worse, and nobody will feel sorry for them.

In response to the veto, some SB 1047 proponents seem to be threatening a kind of revenge arc. They failed to get a “light-touch” bill passed, the reasoning seems to be, so instead of trying again, perhaps they should team up with unions, tech “ethics” activists, disinformation “experts,” and other, more ambiently anti-technology actors for a much broader legislative effort. Get ready, they seem to be warning, for “use-based” regulation of epic proportions. As Rob Wiblin, one of the hosts of the Effective Altruist-aligned 80,000 Hours podcast put it on X:

» “Having failed to get up a narrow bill focused on frontier models, should AI x-risk folks join a popular front for an Omnibus AI Bill that includes SB1047 but adds regulations to tackle union concerns, actor concerns, disinformation, AI ethics, current safety, etc?”Last year, I would have told Dean not to worry about us allying with the Left - the Left would never accept an alliance with the likes of us anyway. But I was surprised by how fairly socialist media covered the SB 1047 fight. For example, from Jacobin:

This is one plausible strategic response the safety community—to the extent it is a monolith—could pursue. We even saw inklings of this in the final innings of the SB 1047 debate, after bill co-sponsor Encode Justice recruited more than one hundred members of the actors’ union SAG-AFTRA to the cause. These actors (literal actors) did not know much about catastrophic risk from AI—some of them even dismiss the possibility and supported SB 1047 anyway! Instead, they have a more generalized dislike of technology in general and AI in particular. This group likes anything that “hurts AI,” not because they care about catastrophic risk, but because they do not like AI.

The AI safety movement could easily transition from being a quirky, heterodox, “extremely online” movement to being just another generic left-wing cause. It could even work.

But I hope they do not. As I have written consistently, I believe that the AI safety movement, on the whole, is a long-term friend of anyone who wants to see positive technological transformation in the coming decades. Though they have their concerns about AI, in general this is a group that is pro-science, techno-optimist, anti-stagnation, and skeptical of massive state interventions in the economy (if I may be forgiven for speaking broadly about a diverse intellectual community).

I hope that we can work together, as a broadly techno-optimist community, toward some sort of consensus. One solution might be to break SB 1047 into smaller, more manageable pieces. Should we have audits for “frontier” AI models? Should we have whistleblower protections for employees at frontier labs? Should there be transparency requirements of some kind on the labs? I bet if the community put legitimate effort into any one of these issues, something sensible would emerge.

The cynical, and perhaps easier, path would be to form an unholy alliance with the unions and the misinformation crusaders and all the rest. AI safety can become the “anti-AI” movement it is often accused of being by its opponents, if it wishes. Given public sentiment about AI, and the eagerness of politicians to flex their regulatory biceps, this may well be the path of least resistance.

The harder, but ultimately more rewarding, path would be to embrace classical motifs of American civics: compromise, virtue, and restraint.

I believe we can all pursue the second, narrow path. I believe we can be friends. Time will tell whether I, myself, am hopelessly naïve.

The debate playing out in the public square may lead you to believe that we have to choose between addressing AI’s immediate harms and its inherently speculative existential risks. And there are certainly trade-offs that require careful consideration.In short, it’s capitalism versus humanity.

But when you look at the material forces at play, a different picture emerges: in one corner are trillion-dollar companies trying to make AI models more powerful and profitable; in another, you find civil society groups trying to make AI reflect values that routinely clash with profit maximization.

Current Affairs, another socialist magazine, also had a good article, Surely AI Safety Legislation Is A No-Brainer. The magazine’s editor, Nathan Robinson, openly talked about how his opinion had shifted:

One thing I’ve changed some of my opinions about in the last few years is AI. I used to think that most of the claims made about its radically socially disruptive potential (both positive and negative) were hype. That was in part because they often came from the same people who made massively overstated claims about cryptocurrency. Some also resembled science fiction stories, and I think we should prioritize things we know to be problems in the here and now (climate catastrophe, nuclear weapons, pandemics) than purely speculative potential disasters. Given that Silicon Valley companies are constantly promising new revolutions, I try to always remember that there is a tendency for those with strong financial incentives to spin modest improvements, or even total frauds, as epochal breakthroughs.I don’t want to gloss this as “socialists finally admit we were right all along”. I think the change has been bi-directional. Back in 2010, when we had no idea what AI would look like, the rationalists and EAs focused on the only risk big enough to see from such a distance: runaway unaligned superintelligence. Now that we know more specifics, “smaller” existential risks have also come into focus, like AI-fueled bioterrorism, AI-fueled great power conflict, and - yes - AI-fueled inequality. At some point, without either side entirely abandoning their position, the very-near-term-risk people and the very-long-term-risk people have started to meet in the middle.

But as I’ve actually used some of the various technologies lumped together as “artificial intelligence,” over and over my reaction has been: “Jesus, this stuff is actually very powerful… and this is only the beginning.” I think many of my fellow leftists tend to have a dismissive attitude toward AI’s capabilities, delighting in its failures (ChatGPT’s basic math errors and “hallucinations,” the ugliness of much AI-generated “art,” badly made hands from image generators, etc.). There is even a certain desire for AI to be bad at what it does, because nobody likes to think that so much of what we do on a day-to-day basis is capable of being automated. But if we are being honest, the kinds of technological breakthroughs we are seeing are shocking. If I’m training to debate someone, I can ask ChatGPT to play the role of my opponent, and it will deliver a virtually flawless performance. I remember not too many years ago when chatbots were so laughably inept that it was easy to believe one would never be able to pass a Turing Test. Now, ChatGPT not only aces the test but is better at being “human” than most humans. And, again, this is only the start.

The ability to replicate more and more of the functions of human intelligence on a machine is both very exciting and incredibly risky. Personally I am deeply alarmed by military applications of AI in an age of great power competition. The autonomous weapons arms race strikes me as one of the most dangerous things happening in the world today, and it’s virtually undiscussed in the press. The conceivable harms from AI are endless. If a computer can replicate the capacities of a human scientist, it will be easy for rogue actors to engineer viruses that could cause pandemics far worse than COVID. They could build bombs. They could execute massive cyberattacks. From deepfake porn to the empowerment of authoritarian governments to the possibility that badly-programmed AI will inflict some catastrophic new harm we haven’t even considered, the rapid advancement of these technologies is clearly hugely risky. That means that we are being put at risk by institutions over which we have no control.

But I think an equally big change is that SB 1047 has proven that AI doomers are willing to stand up to Big Tech. Socialists previously accused us of being tech company stooges, harping on the dangers of AI as a sneaky way of hyping it up. I admit I dismissed those accusations as part of a strategy of slinging every possible insult at us to see which ones stuck. But maybe they actually believed it. Maybe it was their real barrier to working with us, and maybe - now that we’ve proven we can (grudgingly, tentatively, when absolutely forced) oppose (some) Silicon Valley billionaires, they’ll be willing to at least treat us as potential allies of convenience. [ed. they (I) actually believed it; your problem that you didn't.]

Dean Ball calls this strategy “an unholy alliance with the unions and the misinformation crusaders and all the rest”, and equates it to selling our souls. I admit we have many cultural and ethical differences with socialists, that I don’t want to become them, that I can’t fully endorse them, and that I’m sure they feel the same way about me. But coalition politics doesn’t require perfect agreement. The US and its European allies were willing to form an “unholy alliance” with some unsavory socialists in order to defeat the Nazis, they did defeat the Nazis, and they kept their own commitments to capitalism and democracy intact.

As a wise man once said, politics is the art of the deal. We should see how good a deal we’re getting from Dean, and how good a deal we’re getting from the socialists, then take whichever one is better.

Dean says maybe he and his allies in Big Tech would support a weaker compromise proposal that broke SB 1047 into small parts. But I feel like we watered down SB 1047 pretty hard already, and Big Tech just ignored the concessions, lied about the contents, and told everyone it would destroy California forever. Is there some hidden group of opponents who were against it this time, but would get on board if only we watered it down slightly more? I think the burden of proof is on him to demonstrate that there are.

I respect Dean’s spirit of cooperation and offer of compromise. But the socialists have a saying - “That already was the compromise” - and I’m starting to respect them too. (...)

Some people tell me they wish they’d gotten involved in AI early. But it’s still early! AI is less than 1% of the economy! In a few years, we’re going to look back on these days the way we look back now on punch-card computers.

Even very early, it’s possible to do good object-level work. But the earlier you go, the less important object-level work is compared to shaping possibilities, coalitions, and expectations for the future. So here are some reasons for optimism.

First, we proved we can stand up to (the bad parts of) Big Tech. Without sacrificing our principles or adopting any rhetoric we considered dishonest, we earned some respect from leftists and got some leads on potential new friends.

Second, we registered our beliefs (AI will soon be powerful and potentially dangerous) loudly enough to get the attention of the political class and the general public. And we forced our opponents to register theirs (AI isn’t scary and doesn’t require regulation) with equal volume. In a few years, when the real impact of advanced AI starts to come into focus, nobody will be able to lie about which side of the battle lines they were on.

Third, we learned - partly to our own surprise - that we have the support of ~65% of Californians and an even higher proportion of the state legislature. It’s still unbelievably, fantastically early, comparable to people trying to build an airplane safety coalition when da Vinci was doodling pictures of guys with wings - and we already have the support of 65% of Californians and the legislature. So one specific governor vetoed one specific bill. So what? This year we got ourselves the high ground / eternal glory / social capital of being early to the fight. Next year we’ll get the actual policy victory. Or if not next year, the year after, or the year after that. “Instead of planning a path to victory, plan so that all paths lead to victory”. We have strategies available that people from lesser states can’t even imagine!

Jane Graverol, Still Life. Born November 25, 1907 in Ixelles and died April 24, 1984 in Fontainebleau, Belgian surrealist painter.

The Joy of Clutter

In the late 20th century, Japan was known for its minimalism: its Zen arts, its tidy and ordered cities, its refined foods and fashions. But Tsuzuki peeled away this façade to reveal a more complicated side to his nation. And Tokyo was the perfect setting for this exfoliation. Like the interiors he photographed, it remains visually overwhelming – even cluttered. Outside, enormous animated advertisements compete for attention against a jigsaw puzzle of metal, glass, concrete and plastic. In the sprawling residential districts that radiate from the city centre, compact homes are packed in formations as dense as transistors on a semiconductor chip, while confusing geometries of power lines spiderweb the skies above.

In suburbs across the nation, homes filled to the rafters with hoarded junk are common enough to have an ironic idiom: gomi-yashiki (trash-mansions). And in areas where space is limited, cluttered residences and shops will often erupt, disgorging things onto the street in a semi-controlled jumble so ubiquitous that urban planners have a name for it: afuré-dashi (spilling-outs). This is an ecstatic, emergent complexity, born less from planning than from organic growth, from the inevitable chaos of lives being lived.

Tsuzuki dismissed the West’s obsession with Japanese minimalism as ‘some Japanophile’s dream’ in the introduction to the English translation of Tokyo: A Certain Style (1999). ‘Our lifestyles are a lot more ordinary,’ he explained. ‘We live in cozy wood-framed apartments or mini-condos crammed to the gills with things.’ Yet more than three decades after Tsuzuki tried to wake the dreaming Japanophile, the outside world still worships Japan for its supposed simplicity, minimalism and restraint. You can see it in the global spread of meticulously curated Japanese cuisine, the deliberately unadorned concrete of modernist architects like Tadao Andō, and even through minimalist brands like Muji – whose very name translates into ‘the absence of a brand’ in Japanese. (...)

All of this paved the way for Marie Kondo, whose Jinsei wo Tokimeku Katazuke no Maho (‘Tidying Magic to Make Your Life Shine’) arrived in 2011. She singled out Tatsumi by name in the first chapter, and unabashedly wove Shintō spiritual traditions into her method. The English translation, retitled The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing (2014), came out in the US three years later. The subtitle is telling: now decluttering was no longer a form of housework but an Art, with a capital A, echoing austere pastimes such as inkbrush-painting or the tea ceremony. (...)

There was just one issue. In the hyperconsumer societies of Japan and the West, minimalism is extraordinarily difficult to achieve, let alone maintain over the long term. If it were easy, we wouldn’t regard gurus like Kondo with such awe, nor would we be moved by the austerity of Zen temples or Shintō shrines. They exist as a counterpoint to our mundane lives. And think back to Tsuzuki’s pictures of Tokyo homes. They hinted, even insisted, that a life surrounded by stuff wasn’t unusual or pathological. It could be invigorating, even nourishing. If the people in Tsuzuki’s anti-tidying manifesto could make it work, was clutter really the problem? (...)

Cosily curated Japanese clutter-spaces are different. There is a meticulousness to the best of them that is on a par with the mental effort poured into simplifying something: a deliberate aesthetic decision to add, rather than subtract – sometimes mindfully, sometimes unconsciously, but always, always individually. Clutter offers an antidote to the stupefying standardisation of so much of modern life.