Monday, October 5, 2020

Lockdown Feels Pretty Different the Second Time Around

The next day I spoke to my father in Jerusalem, where the country’s first death from coronavirus had just been recorded. We both danced around the fact that, since his age made him more susceptible to complications from the virus, it would probably be a long time before we could see each other.

Movement was restricted to within 100 meters (about 330 feet) from one’s home. I taped to our fridge a “schedule” for my children, who were 3½ and 1½, which included assembling puzzles in the living room, coloring on our tiny porch and tent-building in their room. Five days later, I scrapped the “schedule” because every unfilled task felt like a personal failure. When my husband got off work (our dining table became his home office), I would lock myself on the porch with the shutters down to write.

On May 26, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, eager to score a win after barely scraping by in the latest election, declared that we had managed to flatten the curve. Israel had suffered 281 deaths and more than 16,000 people had been infected, but the new infections had dropped to a few dozen cases. “Go have fun!” he said.

The government reopened schools, allowed indoor dining, stopped enforcing social distancing in shopping malls and permitted large weddings. These reckless decisions reversed the public health gains of the first lockdown.

Cases started to spike to over 8,000 a day and hospital beds filled perilously close to capacity by September, and it became clear that another closure was inevitable. On Sept. 18, the government imposed a second national lockdown. But it did not feel like déjà vu.

Whatever trust Israelis had had in the government to lead us through the pandemic has evaporated. The sense of national solidarity — the kind of wartime singleness of purpose that characterized the first lockdown — has been replaced by what can only be described as a free-for-all.

by Ruth Margalit, NY Times | Read more:

Image:Amir Cohen/Reuters

Sunday, October 4, 2020

Cinema Therapy: The Sequel

Jane: Half the people I know feel that way. The lucky ones feel that way. The rest of the people ARE hysterical twenty-four hours a day.

— from Grand Canyon, screenplay by Lawrence and Meg Kasdan

HAL 9000: Look Dave, I can see you’re really upset about this. I honestly think you ought to sit down calmly, take a stress pill, and think things over.

— from 2001: A Space Odyssey, screenplay by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke

George Fields: [to Dorothy/Michael] I BEGGED you to get therapy!

— from Tootsie, screenplay by Larry Gelbart and Murray Schisgal

Man…2020 has been one long, strange century.

As Howard Beale once said, “I don’t have to tell you things are bad. Everybody knows things are bad.” Four score and seven years ago (back in March), when portions of America went into a pandemic-driven lock down and our nation turned its lonely eyes to Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime and other streaming platforms in a desperate search for binge-worthy distraction, I published a post sharing 10 of my favorite “therapy movies”.

Now its October (where have the decades gone?) and things are…unsettled. The news cycle of this past week has been particularly trying for those of us who follow that sort of thing (which I assume to be “most of us” who gravitate to this corner of the blogosphere).

With that in mind, here are 10 more personal faves that I’ve watched an unhealthy number of times; films I’m most likely to reach for when I’m depressed, feeling anxious, uncertain about the future…or all the above. These films, like my oldest and dearest friends, have never, ever let me down. Take one or two before bedtime; cocktail optional. (...)

The effervescent Maude is Harold’s opposite; while he wallows in morbid speculation how any day could be your last, she seizes each day as if it actually were. Obviously, she has something to teach him. Despite dark undertones, this is one “midnight movie” that somehow manages to be life-affirming. The late Hal Ashby directed, and Colin Higgins wrote the screenplay. The memorable soundtrack is by Cat Stevens.

The Masque of the Red Death

But the Prince Prospero was happy and dauntless and sagacious. When his dominions were half depopulated, he summoned to his presence a thousand hale and light-hearted friends from among the knights and dames of his court, and with these retired to the deep seclusion of one of his castellated abbeys. This was an extensive and magnificent structure, the creation of the prince's own eccentric yet august taste. A strong and lofty wall girdled it in. This wall had gates of iron. The courtiers, having entered, brought furnaces and massy hammers and welded the bolts. They resolved to leave means neither of ingress nor egress to the sudden impulses of despair or of frenzy from within. The abbey was amply provisioned. With such precautions the courtiers might bid defiance to contagion. The external world could take care of itself. In the meantime it was folly to grieve, or to think. The prince had provided all the appliances of pleasure. There were buffoons, there were improvisatori, there were ballet-dancers, there were musicians, there was Beauty, there was wine. All these and security were within. Without was the "Red Death".

It was towards the close of the fifth or sixth month of his seclusion, and while the pestilence raged most furiously abroad, that the Prince Prospero entertained his thousand friends at a masked ball of the most unusual magnificence. (...)

He had directed, in great part, the movable embellishments of the seven chambers, upon occasion of this great fête; and it was his own guiding taste which had given character to the masqueraders. Be sure they were grotesque. There were much glare and glitter and piquancy and phantasm—much of what has been since seen in "Hernani". There were arabesque figures with unsuited limbs and appointments. There were delirious fancies such as the madman fashions. There were much of the beautiful, much of the wanton, much of the bizarre, something of the terrible, and not a little of that which might have excited disgust. To and fro in the seven chambers there stalked, in fact, a multitude of dreams. And these—the dreams—writhed in and about taking hue from the rooms, and causing the wild music of the orchestra to seem as the echo of their steps. And, anon, there strikes the ebony clock which stands in the hall of the velvet. And then, for a moment, all is still, and all is silent save the voice of the clock. The dreams are stiff-frozen as they stand. But the echoes of the chime die away—they have endured but an instant—and a light, half-subdued laughter floats after them as they depart. And now again the music swells, and the dreams live, and writhe to and fro more merrily than ever, taking hue from the many tinted windows through which stream the rays from the tripods. But to the chamber which lies most westwardly of the seven, there are now none of the maskers who venture; for the night is waning away; and there flows a ruddier light through the blood-coloured panes; and the blackness of the sable drapery appals; and to him whose foot falls upon the sable carpet, there comes from the near clock of ebony a muffled peal more solemnly emphatic than any which reaches their ears who indulged in the more remote gaieties of the other apartments.

But these other apartments were densely crowded, and in them beat feverishly the heart of life. And the revel went whirlingly on, until at length there commenced the sounding of midnight upon the clock. And then the music ceased, as I have told; and the evolutions of the waltzers were quieted; and there was an uneasy cessation of all things as before. But now there were twelve strokes to be sounded by the bell of the clock; and thus it happened, perhaps, that more of thought crept, with more of time, into the meditations of the thoughtful among those who revelled. And thus too, it happened, perhaps, that before the last echoes of the last chime had utterly sunk into silence, there were many individuals in the crowd who had found leisure to become aware of the presence of a masked figure which had arrested the attention of no single individual before. And the rumour of this new presence having spread itself whisperingly around, there arose at length from the whole company a buzz, or murmur, expressive of disapprobation and surprise—then, finally, of terror, of horror, and of disgust.

In an assembly of phantasms such as I have painted, it may well be supposed that no ordinary appearance could have excited such sensation. In truth the masquerade licence of the night was nearly unlimited; but the figure in question had out-Heroded Herod, and gone beyond the bounds of even the prince's indefinite decorum. There are chords in the hearts of the most reckless which cannot be touched without emotion. Even with the utterly lost, to whom life and death are equally jests, there are matters of which no jest can be made. The whole company, indeed, seemed now deeply to feel that in the costume and bearing of the stranger neither wit nor propriety existed. The figure was tall and gaunt, and shrouded from head to foot in the habiliments of the grave. The mask which concealed the visage was made so nearly to resemble the countenance of a stiffened corpse that the closest scrutiny must have had difficulty in detecting the cheat. And yet all this might have been endured, if not approved, by the mad revellers around. But the mummer had gone so far as to assume the type of the Red Death. His vesture was dabbled in blood—and his broad brow, with all the features of the face, was besprinkled with the scarlet horror.

Thursday, October 1, 2020

Say Goodbye to Hold Music

Save time with Hold for Me

Hold for Me is our latest effort to make phone calls better and save you time. Last year, we introduced an update to Call Screen that helps you avoid interruptions from spam calls once and for all, and last month, we launched Verified Calls to help you know why a business is calling before you answer. Hold for Me is now another way we’re making it simpler to say hello.

Powered by Google AI

Every business’s hold loop is different and simple algorithms can't accurately detect when a customer support representative comes onto the call. Hold for Me is powered by Google’s Duplex technology, which not only recognizes hold music but also understands the difference between a recorded message (like “Hello, thank you for waiting”) and a representative on the line. Once a representative is identified, Google Assistant will notify you that someone’s ready to talk and ask the representative to hold for a moment while you return to the call. We gathered feedback from a number of companies, including Dell and United, as well as from studies with customer support representatives, to help us design these interactions and make the feature as helpful as possible to the people on both sides of the call.

While Google Assistant waits on hold for you, Google’s natural language understanding also keeps you informed. Your call will be muted to let you focus on something else, but at any time, you can check real-time captions on your screen to know what’s happening on the call.

Keeping your data safe

Hold for Me is an optional feature you can enable in settings and choose to activate during each call to a toll-free number. To determine when a representative is on the line, audio is processed entirely on your device and does not require a Wi-Fi or data connection. This makes the experience fast and also protects your privacy—no audio from the call will be shared with Google or saved to your Google account unless you explicitly decide to share it and help improve the feature. When you return to the call after Google Assistant was on hold for you, audio stops being processed altogether.

We’re excited to bring an early preview of Hold for Me to our latest Pixel devices and continue making the experience better over time. Your feedback will help us bring the feature to more people over the coming months, so they too can say goodbye to hold music and say hello to more free time.

by Andrew Goodman and Joseph Cherukara, Google | Read more:

Image: Google

Lily He

[ed. The Men's PGA Tour is so far removed from my game I frequently watch the LPGA Women's Tour instead. There are other reasons, too.]

The Rules Have Changed

I was asked to speak, from an outsider’s perspective, about the “rules of the game” in politics, and how the current practice of representative democracy in Washington looks to a person out in the hinterlands. As we move now toward another contentious Supreme Court confirmation, I’ve taken a special interest in a certain set of rules that have governed the Senate, especially concerning the “advice and consent” responsibilities with regard to presidential appointments of federal judges. The Senate, as we all know, has lately been embroiled in controversy over the matter of Supreme Court nominations. This body has created a great deal of confusion on the simple question of whether vacancies should or should not be filled during an election year. You’re about to do it now, and in an especially hurried manner, with only weeks to go before the presidential election. And yet many of us were told only four years ago that such things ought never happen in a Senate that respects the voters.

To prepare for this testimony, I have studied carefully the public statements of leading senators, giving special attention to principles stated by Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky and Senate Judiciary Chairman Lindsey Graham of South Carolina. These are two of the most experienced senators in this Congress, so it stands to reason they would have deeply considered beliefs about rules that promote fairness in the democratic process. Let us consider their views.

It is well known that Senator McConnell developed a firm conviction after the death of Justice Antonin Scalia in February of 2016 that vacancies on the Supreme Court should not be filled in an election year. His statement at that time was: “The American people should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court Justice. Therefore, this vacancy should not be filled until we have a new president.” Just about every Republican senator echoed this stance. Senator Graham explained it further: “We’re setting a precedent here today, Republicans are, that in the last year—at least of a lame-duck eight-year term, I would say it’s going to [apply to] a four-year term—that you’re not going to fill a vacancy of the Supreme Court, based on what we’re doing here today. That’s going to be the new rule.” As McConnell often noted, others had previously advocated such a rule, including the former senator from Delaware, Joe Biden. Therefore, President Obama’s nominee in 2016, Judge Merrick Garland, was deprived of a hearing and a vote and the seat was not filled until the following year, after Obama left office.

What is the core democratic principle that senators so passionately articulated here? It is “the American people should have a voice.” Of course, the voters had a voice in choosing the sitting president, and the president’s constitutional power is to nominate justices to the Supreme Court. The voters also chose the Senate, which has the constitutional power to withhold consent. But as an election approaches, McConnell seemed to believe, the president’s power is nullified. In the final year of his term, he loses his power to fill court vacancies. However, the Senate’s power is not nullified. Those senators who are also in their final year of a term do not lose their power to veto the president, or to confirm a nominee if they so choose.

So “the American people should have a voice” does not sufficiently explain the principle at work. We now know that Senator McConnell and Senator Graham spoke simplistically in explaining their stance against an Obama appointment. As we learned in 2020, the new rule was not, as Graham said, “that in the last year . . . you’re not going to fill a vacancy.” Once a vacancy was created by the recent death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, both McConnell and Graham clarified that election-year appointments to the bench are acceptable—even as close as a month before the voters go to the polls—if the presidency and the Senate are controlled by the same party. In this case, there would be no need to wait to hear the voice of the American people, because they’ve already spoken through the results of the previous election, not the upcoming one. Once again, just about every Republican senator immediately echoed this stance.

In explaining how the rule really works, McConnell has clarified that certain past elections are more important than others. Obama’s reelection mandate in 2012 was mitigated by the midterm election of 2014, in which Republicans were granted a 54-46 Senate majority. Divided government is what caused the president to lose his power to appoint judges. It was the vote in 2014 that expressed the true will of the people, not the one in 2012.

The Republicans lost a couple of Senate seats in 2016 but managed to secure the presidency and hold the Senate. And after the 2018 midterms, they enjoyed a 53-47 majority. Therefore “the American people” were presumed to be voicing their support for the Republican agenda. You might conclude from the statements of our principled leaders that what guides their decision-making is deep respect for the opinions of the American people as discerned from election results. Let us then look a little closer at the partisan opinions of voters.

How are we to understand majority opinion—for that is what McConnell is claiming gives the GOP its mandate—other than by counting the number of votes? Certainly he would not claim that ten thousand votes have more weight than twenty thousand votes. It seems essential to note, then, that Barack Obama was elected in 2012 with 62.6 million votes. Two years later, Mitch McConnell was re-elected to the Senate in Kentucky with less than 2 percent of the president’s backing: 806,787 votes. Yet McConnell knows that the rules allow him to arrogate almost as much power as the president. That power gives him deep satisfaction, as we saw when he told a group of supporters in Kentucky, “One of my proudest moments was when I looked at Barack Obama in the eye and I said, ‘Mr. President, you will not fill this Supreme Court vacancy.’”

We understand, though, that the Majority Leader’s power derives not just from his own voters, but from the support of his Republican caucus. So we might ask how many voters the full Republican majority represents. And here’s the awful truth: if you add up the votes most recently won by each of the current fifty-three GOP senators—the class produced by the elections of 2014, 2016, and 2018—it comes to 55.1 million. Not only is that quite short of the 62.6 million votes for Obama in 2012, it’s less than the 65.8 million votes Hillary Clinton won as she edged out Donald Trump in the 2016 popular vote. But there’s one total that’s even higher than that: today’s forty-five Democratic senators together won their seats with 68.1 million votes. (Add in the two independents—Sanders of Vermont and King of Maine—and the total comes to 68.7 million.) Imagine that: the minority of forty-seven senators was elected with about 5.7 million more votes than President Trump received in 2016.

Though we are discussing the Senate, we should also note the recent election results in the House of Representatives, which reflect the will of the voters more reliably than Senate races do. Recall that the Republican leadership put great stock in their gains in the midterm elections of 2014, which they interpreted as a rejection of President Obama (creating the “divided government” that made it appropriate to stymie his judicial nominations). Yet today they ignore the Democratic wave election of 2018, which suggested a rejection of President Trump’s agenda. Democrats gained forty seats in the 2018 midterms, giving them a 235-200 majority in the House. Did this suggest a questionable mandate for the president? The Democratic House candidates that year racked up 60.7 million votes. The Republican candidates won just under 51 million votes.

So again, we must ask: What is the core principle Leader McConnell is acting on? It is not that “the American people” should have a chance to vote for a new president before another lifetime appointment to the High Court is made. Nor is it that they have already sanctioned an election-season choice by giving Republicans the White House and the Senate—neither the president nor the GOP Senate majority won majority support from the electorate. To state the principle honestly, McConnell would have to acknowledge it’s not the majority opinion of the American people that matters, it’s the unbalanced power of the states. Kentucky stands on equal footing with California in deciding upon these lifetime appointments. So I would suggest to you that the McConnell Rule amounts to this: “Supreme Court appointments are acceptable in an election year when a few large conservative states with active voter suppression programs (Texas, Florida, and Georgia) combine with mostly rural low-population states to elect a president and a Senate without an electoral majority.” This is what he calls a “united government” with a clear mandate.

I’m sure many of you on this distinguished panel are aware of the bitter partisan complaints that have been engendered by Leader McConnell’s governing style. He has been called a cynic, a “dollar-store Machiavelli,” and “the gravedigger of American democracy.” And yet those of us who have studied his career know he sees himself as a devoted student of the Constitution and the rules of the Senate. We can be sure he would be little interested in the critique of his inconsistent rationales that I have outlined here. The fact that Republicans hold power in the Senate with 13.6 million fewer votes in their column than Democratic senators is simply an artifact of our constitutional structure. And it is the states that choose the president through the Electoral College, not the people through the national vote. Majority Leader McConnell operates within this constitutional framework and no doubt sleeps easily at night in his conviction that he faithfully follows the letter of the laws.

But we are here today to discuss rules. We are well aware that the rules of the Senate, both the written and unwritten ones, change over time. Senator Lindsey Graham has given us a good understanding of how mercurial and emotional the rule-making process of the Senate can be. He sounded firm in his conviction in 2016 when he declared “the new rule” against filling Supreme Court vacancies in an election year. In explaining his change of heart in a letter to his fellow senators recently, he confessed he was still angry over the way Democrats treated Brett Kavanaugh, and for that matter Robert Bork, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito, when they appeared before the Senate for confirmation hearings. Consequently, Graham recently explained, “the rules have changed.”

I think we can all agree that spite is not necessarily the highest justification for changing the rules. If you haven’t thought more than a few minutes about the question, you might take the high-minded stand that seeking partisan advantage is not a good justification, either. But what do we do when partisan advantage is inherent in existing rules? The pursuit of new rules is bound to either add to those advantages or to reverse them. There is no neutrality in politics. Yet, there ought to be a pursuit of fairness. This is a sports-crazed nation: everyone should be able to understand the problem if a basketball game is played with one team getting four points for every shot made from behind the “three-point” line, while the other team gets only two points.

It seems to me to be a damn shame that we don’t currently have a political party that is willing to stand up and fight for the true interests of the American voter.

We have seen the results of crafty Republican partisanship: control of the presidency, the Senate, and many state legislatures, all as part of a drive to impose minority rule on the rest of us. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party fails to defend essential principles of fairness and democracy. I saw the other day a Republican strategist quoted by a newspaper columnist claiming that Mitch McConnell and the Democrats’ Senate leader Chuck Schumer “play the same game. McConnell just plays it a little better.” This is wrong on both counts. Minority Leader Schumer plays a different game. He and others in the Democratic leadership believe they can impress voters by acting like reasonable and civil moderates who “play by the rules,” which are stacked against them. We also can’t know whether McConnell truly plays the game better. He uses a structure that gives him many built-in advantages.

The difference is that he is willing to use the rules—and change the rules—in whatever ways benefit his party’s hold on power. So I now come to my modest proposals. These are premised on the possibility that the Democratic Party will someday win back control of the White House and the Senate, while holding a majority in the House. And further, that leaders of the Democratic Party might decide to remake the party as a powerful force for a functioning and fair democracy.

by Dave Denison, The Baffler | Read more:

Wednesday, September 30, 2020

Tuesday, September 29, 2020

The Love That Lays the Swale in Rows

If that sounds naive or hopeless, it’s because we have been misled by a metaphor. We’ve defined our relation with technology not as that of body and limb or even that of sibling and sibling but as that of master and slave. The idea goes way back. It took hold at the dawn of Western philosophical thought, emerging first with the ancient Athenians. Aristotle, in discussing the operation of households at the beginning of his Politics, argued that slaves and tools are essentially equivalent, the former acting as “animate instruments” and the latter as “inanimate instruments” in the service of the master of the house. If tools could somehow become animate, Aristotle posited, they would be able to substitute directly for the labor of slaves. “There is only one condition on which we can imagine managers not needing subordinates, and masters not needing slaves,” he mused, anticipating the arrival of computer automation and even machine learning. “This condition would be that each [inanimate] instrument could do its own work, at the word of command or by intelligent anticipation.” It would be “as if a shuttle should weave itself, and a plectrum should do its own harp-playing.”

The conception of tools as slaves has colored our thinking ever since. It informs society’s recurring dream of emancipation from toil. “All unintellectual labour, all monotonous, dull labour, all labour that deals with dreadful things, and involves unpleasant conditions, must be done by machinery,” wrote Oscar Wilde in 1891. “On mechanical slavery, on the slavery of the machine, the future of the world depends.” John Maynard Keynes, in a 1930 essay, predicted that mechanical slaves would free humankind from “the struggle for subsistence” and propel us to “our destination of economic bliss.” In 2013, Mother Jones columnist Kevin Drum declared that “a robotic paradise of leisure and contemplation eventually awaits us.” By 2040, he forecast, our computer slaves—“they never get tired, they’re never ill-tempered, they never make mistakes”—will have rescued us from labor and delivered us into a new Eden. “Our days are spent however we please, perhaps in study, perhaps playing video games. It’s up to us.”

With its roles reversed, the metaphor also informs society’s nightmares about technology. As we become dependent on our technological slaves, the thinking goes, we turn into slaves ourselves. From the eighteenth century on, social critics have routinely portrayed factory machinery as forcing workers into bondage. “Masses of labourers,” wrote Marx and Engels in their Communist Manifesto, “are daily and hourly enslaved by the machine.” Today, people complain all the time about feeling like slaves to their appliances and gadgets. “Smart devices are sometimes empowering,” observed The Economist in “Slaves to the Smartphone,” an article published in 2012. “But for most people the servant has become the master.” More dramatically still, the idea of a robot uprising, in which computers with artificial intelligence transform themselves from our slaves to our masters, has for a century been a central theme in dystopian fantasies about the future. The very word “robot,” coined by a science fiction writer in 1920, comes from robota, a Czech term for servitude.

The master-slave metaphor, in addition to being morally fraught, distorts the way we look at technology. It reinforces the sense that our tools are separate from ourselves, that our instruments have an agency independent of our own. We start to judge our technologies not on what they enable us to do but rather on their intrinsic qualities as products—their cleverness, their efficiency, their novelty, their style. We choose a tool because it’s new or it’s cool or it’s fast, not because it brings us more fully into the world and expands the ground of our experiences and perceptions. We become mere consumers of technology.

The metaphor encourages society to take a simplistic and fatalistic view of technology and progress. If we assume that our tools act as slaves on our behalf, always working in our best interest, then any attempt to place limits on technology becomes hard to defend. Each advance grants us greater freedom and takes us a stride closer to, if not utopia, then at least the best of all possible worlds. Any misstep, we tell ourselves, will be quickly corrected by subsequent innovations. If we just let progress do its thing, it will find remedies for the problems it creates. “Technology is not neutral but serves as an overwhelming positive force in human culture,” writes one pundit, expressing the self-serving Silicon Valley ideology that in recent years has gained wide currency. “We have a moral obligation to increase technology because it increases opportunities.” The sense of moral obligation strengthens with the advance of automation, which, after all, provides us with the most animate of instruments, the slaves that, as Aristotle anticipated, are most capable of releasing us from our labors.

The belief in technology as a benevolent, self-healing, autonomous force is seductive. It allows us to feel optimistic about the future while relieving us of responsibility for that future. It particularly suits the interests of those who have become extraordinarily wealthy through the labor-saving, profit-concentrating effects of automated systems and the computers that control them. It provides our new plutocrats with a heroic narrative in which they play starring roles: job losses may be unfortunate, but they’re a necessary evil on the path to the human race’s eventual emancipation by the computerized slaves that our benevolent enterprises are creating. Peter Thiel, a successful entrepreneur and investor who has become one of Silicon Valley’s most prominent thinkers, grants that “a robotics revolution would basically have the effect of people losing their jobs.” But, he hastens to add, “it would have the benefit of freeing people up to do many other things.” Being freed up sounds a lot more pleasant than being fired.

There’s a callousness to such grandiose futurism. As history reminds us, high-flown rhetoric about using technology to liberate workers often masks a contempt for labor. It strains credulity to imagine today’s technology moguls, with their libertarian leanings and impatience with government, agreeing to the kind of vast wealth-redistribution scheme that would be necessary to fund the self-actualizing leisure-time pursuits of the jobless multitudes. Even if society were to come up with some magic spell, or magic algorithm, for equitably parceling out the spoils of automation, there’s good reason to doubt whether anything resembling the “economic bliss” imagined by Keynes would ensue.

In a prescient passage in The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt observed that if automation’s utopian promise were actually to pan out, the result would probably feel less like paradise than like a cruel practical joke. The whole of modern society, she wrote, has been organized as “a laboring society,” where working for pay, and then spending that pay, is the way people define themselves and measure their worth. Most of the “higher and more meaningful activities” revered in the distant past have been pushed to the margin or forgotten, and “only solitary individuals are left who consider what they are doing in terms of work and not in terms of making a living.” For technology to fulfill humankind’s abiding “wish to be liberated from labor’s ‘toil and trouble’ ” at this point would be perverse. It would cast us deeper into a purgatory of malaise. What automation confronts us with, Arendt concluded, “is the prospect of a society of laborers without labor, that is, without the only activity left to them. Surely, nothing could be worse.” Utopianism, she understood, is a form of self-delusion.

Writing a Book: Is It Worth It?

To me, the success of this book was totally unexpected: while I was writing it, I thought that it was going to be a bit niche, and I set myself the goal of selling 10,000 copies over the lifetime of the book. Having passed that goal tenfold, this seems like a good opportunity to look back and reflect on the process. I don’t want to make this post too self-congratulatory, but rather I will try to share some insights into the business of book-writing.

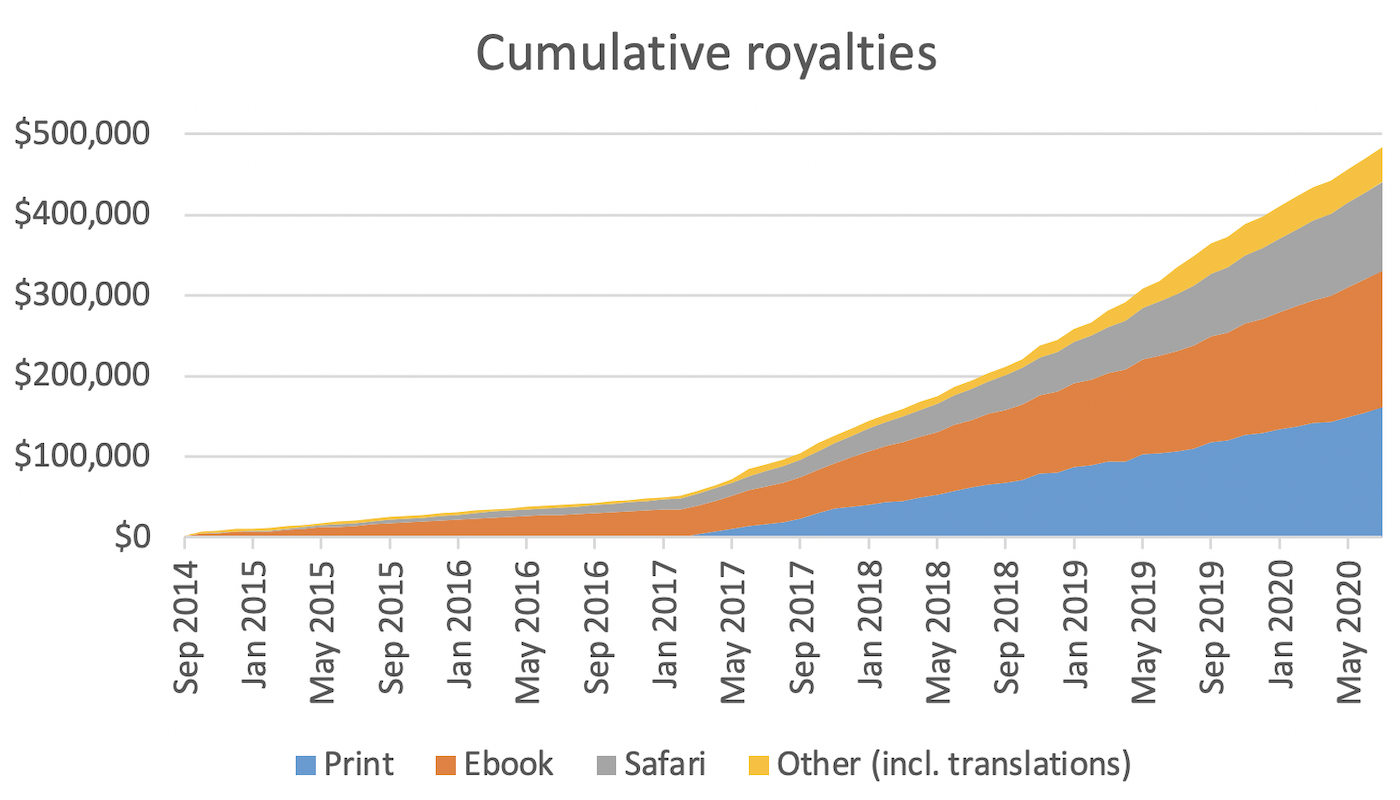

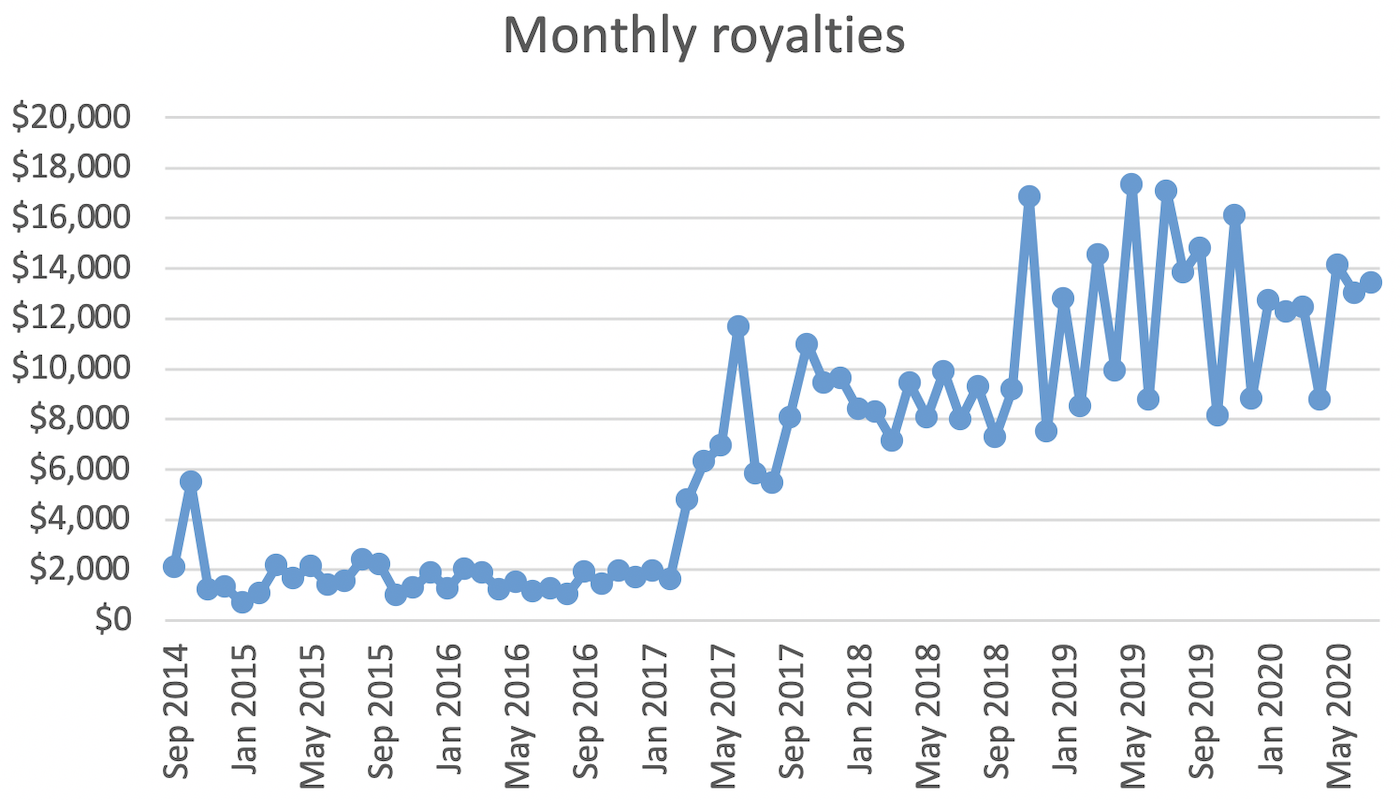

For the first 2½ years the book was in “early release”: during this period I was still writing, and we released it in unedited form, one chapter at a time, as ebook only. Then in March 2017 the book was officially published, and the print edition went on sale. Since then, the sales have fluctuated from month to month, but on average they have stayed remarkably constant. At some point I would expect the market to become saturated (i.e. most people who were going to buy the book have already bought it), but that does not seem to have happened yet: indeed, sales noticeably increased in late 2018 (I don’t know why). The x axis ends in July 2020 because from the time of sale, it takes a couple of months for the money to trickle through the system.

My contract with the publisher specifies that I get 25% of publisher revenue from ebooks, online access, and licensing, 10% of revenue from print sales, and 5% of revenue from translations. That’s a percentage of the wholesale price that retailers/distributors pay to the publisher, so it doesn’t include the retailers’ markup. The figures in this section are the royalties I was paid, after the retailer and publisher have taken their cut, but before tax.

The total sales since the beginning have been (in US dollars):

- Print: 68,763 copies, $161,549 royalties ($2.35/book)

- Ebook: 33,420 copies, $169,350 royalties ($5.07/book)

- O’Reilly online access (formerly called Safari Books Online): $110,069 royalties (I don’t get readership numbers for this channel)

- Translations: 5,896 copies, $8,278 royalties ($1.40/book)

- Other licensing and sponsorship: $34,600 royalties

- Total: 108,079 copies, $477,916

Now, in retrospect, it turns out that those 2.5 years were a good investment, because the income that this work has generated is in the same ballpark as the Silicon Valley software engineering salary (including stock and benefits) I could have received in the same time if I hadn’t quit LinkedIn in 2014 to work on the book. But of course I didn’t know that at the time! The royalties could easily have turned out to be a factor of 10 lower, in which case it would have been a financially much less compelling proposition.

by Martin Kleppmann | Read more:

Images: Martin Kleppmann

Social Cooling

Big Data is supercharging this effect.

This could limit your desire to take risks or exercise free speech.

Over the long term these 'chilling effects' could 'cool down' society.

[ed. Comments (Hacker News).]

Monday, September 28, 2020

Antidote to COVID-19 Science Overload

The wall-to-wall coverage has eased since then, but the pace of discovery hasn’t. Every day, hundreds of new research papers are published or posted about the virus and pandemic, ranging from case studies of single patients to randomized, controlled trials of potential treatments.

It’s a fire hose of information that overwhelms even the most fervent COVID-19 science junkies.

But there’s a way to keep current without having to spend your days and nights clicking through journal websites. For the past five months, a small group of faculty and students at the University of Washington has been wading through the deluge so you don’t have to. Five days a week, the Alliance for Pandemic Preparedness produces the “COVID-19 Literature Situation Report,” which provides a succinct summary of key scientific developments.

It’s a quick read and mostly jargon-free in keeping with a target audience that includes not only public health officials, but also politicians, community leaders and the general public. The group also prepares occasional in-depth reports about issues of pressing interest, like the long-term health effects of COVID-19.

The project started as an effort by staff at the Washington Department of Health (DOH) to keep up with rapid-fire developments early in the outbreak. But the agency was stretched too thin and contracted with Guthrie and his colleagues to continue and expand the work.

Their initial distribution list was 40 people. Today, about 1,600 subscribers get the email newsletter, many of whom share it via other websites and online bulletin boards. Guthrie has heard from readers at the CDC and top universities around the country. Members of Gov. Jay Inslee’s staff are on the distribution list.

Producing what the team calls the “LitRep” is a daily deadline dance that starts at 6 a.m. and doesn’t end until Guthrie or his co-leader Dr. Jennifer Ross, an infectious disease specialist at UW Medicine, hit the “send” button about 12 hours later.

Much of the work is done by a rotating group of five students — mostly doctoral candidates in global health or epidemiology — who work in shifts on a kind of virtual assembly line.

The early birds gather the raw materials, using standard search terms to pull all the new studies posted on PubMed, a free government search engine, and medRxiv and bioRxiv, which posts preprints before peer review. They also manually check several high-profile journals, including the Lancet and the New England Journal of Medicine.

“It’s a very distilled version,” said Brandon Guthrie, assistant professor of global health and epidemiology and co-leader of the effort. “What are the most important things (we) need to know that are coming out today?” (...)

The average haul is about 400 papers a day but can range between 200 and 1,000, said Lorenzo Tolentino, who just finished his master’s degree at the UW Department of Global Health and was one of the first students to sign on for the project.

Image: Greg Gilbert / The Seattle Times

Signs of the Times

The family whose Black Lives Matter sign shook their conservative town (The Guardian); and, ‘Trump Street’ starts a bitter fight over political signs, and much more, in the Alaska town of Eagle (Anchorage Daily News)

Sunday, September 27, 2020

How Work Became an Inescapable Hellhole

I get out of bed and yell at Alexa a few times to turn on NPR. I turn on the shower. As it warms up, I check Slack to see if there’s anything I need to attend to as the East Coast wakes up. When I get out of the shower, the radio’s playing something interesting, so while I’m standing there in my towel, I look it up online and tweet it. I get dressed and get my coffee and sit down at the computer, where I spend a solid hour and a half reading things, tweeting things, and waiting for them to get fav’ed. I post one of the stories I read to the Facebook page of 43,000 followers that I’ve been running for a decade. I check back in five minutes to see if anyone’s commented on it. I tell myself I should try to get to work while forgetting this is kind of my work.

I think, I should really start writing. I go to the Google Doc draft open in my browser. Oops, I mean I go to the clothing website to see if the thing I put in my cart last week is on sale. Oops, I actually mean I go back to Slack to drop in a link to make sure everyone knows I’m online and working. I write 200 words in my draft before deciding I should sign that contract for a speaking engagement that’s been sitting in my Inbox of Shame. I don’t have a printer or scanner, and I can’t remember the password for the online document signer. I try to reset the password but it says, quite nicely, that I can’t use any of my last three passwords. Someone is calling with a Seattle area code; they don’t leave a message because my voicemail is full and has been for six months.

I’m in my email and the “Promotions” tab has somehow grown from two to 42 over the course of three hours. The unsubscribe widget I installed a few months ago stopped working when the tech people at work made everyone change their passwords, and now I spend a lot of time deleting emails from West Elm. But wait there’s a Facebook notification: A new post in the group page for the dog rescue where I adopted my puppy! Someone I haven’t spoken to directly since high school has posted something new!

Over on LinkedIn, my book agent is celebrating her fifth work anniversary; so is a former student whose face I vaguely remember. I have lunch and hate-skim a blog I’ve been hate-skimming for years. Trump does a bad tweet. Someone else wrote a bad take. I eke out some more writing between very important-seeming Slack conversations about Joe Jonas’ musculature.

I go on a walk. I get interrupted once, twice, 15 times by one of my group texts. I get home and go to the bathroom, where I have just enough time to look at my phone again. I drive to the grocery store and get stuck at a long stoplight. I pick up my phone, which says, “It looks like you are driving.” I lie to my phone.

I’m checking out at the grocery store and I’m checking email. I’m getting into the car to drive home and I’m texting my friend an inside joke. I’m five minutes from home and I’m checking in with my boyfriend. I’m back at home with a beer and sitting in the backyard and “relaxing” by reading the internet and tweeting and finalizing edits on a piece. I’m texting my mom instead of calling her. I’m posting a dog walk photo to Instagram and wondering if I’ve posted too many dog photos lately. I’m making dinner while asking Alexa to play a podcast where people talk about the news I didn’t really internalize.

I get into bed with the best intention of reading the book on my nightstand but wow, that’s a really funny TikTok. I check my Instagram likes on the dog photo I did indeed post. I check my email and my other email and Facebook. There’s nothing else to check, so somehow I decide it’s a good time to open my Delta app and check on my frequent flyer mile count. Oops, I ran out of book time; better set SleepCycle.

I’m equally ashamed and exhausted writing that description of a pretty standard day in my digital life—and it doesn’t even include all of the additional times I looked at my phone, or checked social media, or went back and forth between a draft and the internet, as I did twice just while writing this sentence. In the United States, one 2013 study found that millennials check their phone 150 times a day; a different 2016 study claimed we log an average of six hours and 19 minutes of scrolling and texting and stressing out over emails per week. No one I know likes their phone. Most people I know even realize that whatever benefits the phone allows—Google Maps, Emergency Calling—are far outweighed by the distraction that accompanies it.

We know this. We know our phones suck. We even know the apps on them were engineered to be addictive. We know that the utopian promises of technology—to make work more efficient, to make connections stronger, to make photos better and more shareable, to make the news more accessible, to make communication easier—have in fact created more work, more responsibility, more opportunities to feel like a failure.

Part of the problem is that these digital technologies, from cell phones to Apple Watches, from Instagram to Slack, encourage our worst habits. They stymie our best-laid plans for self-preservation. They ransack our free time. They make it increasingly impossible to do the things that actually ground us. They turn a run in the woods into an opportunity for self-optimization. They are the neediest and most selfish entity in every interaction I have with others. They compel us to frame experiences, as we are experiencing them, with future captions, and to conceive of travel as worthwhile only when documented for public consumption. They steal joy and solitude and leave only exhaustion and regret. I hate them and resent them and find it increasingly difficult to live without them.

Digital detoxes don’t fix the problem. Moving to the woods and going full Thoreau, for most of us, is simply not an option. The only long-term fix is making the background into foreground: calling out the exact ways digital technologies have colonized our lives, aggravating and expanding our burnout in the name of efficiency.

What these technologies do best is remind us of what we’re not doing: who’s hanging out without us, who’s working more than us, what news we’re not reading. They refuse to allow our consciousness off the hook, in order to do the essential, protective, regenerative work of sublimating and repressing. Instead, they provide the opposite: a nonstop barrage of notifications and reminders and interactions. They bring life to the forefront, constantly, so that we can’t ignore it. They’re not a respite from work—or, as promised, a way to optimize your work. They’re just more work. And six months into a society-throttling pandemic, they’re more inescapable than ever.

by Anne Helen Petersen, Backchannel/Wired | Read more:

Image: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Saturday, September 26, 2020

The Last Days of a Store with the Deck Stacked Against It

“Hear what?” I muttered through my mask as I picked up my grocery bag.

"Hear that the store is closing. September 19 is the last day. We're finished."

The clerk now had my full attention. I had been shopping at the Northway Mall Carrs/Safeway for 34 years. I must have walked between my Airport Heights home and the grocery store thousands of times — in all types of weather. I had been served by several generations of clerks, served well. I probably had spent more money in this store than in any business in Anchorage.

Given there was no one in line behind me, I pushed the clerk for more. “You heard this from a manager, someone in authority, someone who knows? This is not ‘People are sayin.’”

The clerk was right, although when I asked workers why the store was closing, they had differing explanations. Some said Safeway officials didn’t want to remain in a failing mall - a dump. Some said the store had suffered intolerable losses to shoplifters. Some said Mayor Ethan Berkowitz was going to buy the mall and convert it into a homeless shelter.

Well, the Northway Mall is failing — and a dump. The owner long ago stopped investing in the facility. The last paint job must have been laid on before President Bill Clinton met Monica Lewinsky. The parking lot is often full of nasty potholes.

Shoplifting? There was a lot out in the open. Especially at the liquor store, sometimes by obviously homeless people, sometimes by well-dressed men who looked as if they were coming home from work. I watched one of these men laugh at the clerk. “What are you gonna do about it? You caught me this time — you know I’ll be back.”

The Los Angeles Times recently reported “A 2020 survey by the National Retail Federation found that theft — which the industry calls “shrink” — was at an all-time high, costing the industry $61.7 billion in fiscal year 2019, or 1.62% of retailers' profits.” Safeway has not confided in me, but I am betting 1.62% would be way under the percentage for the Northway Mall.

As for setting up the homeless in the mall, this didn’t make any sense on the face of it. For starters, the plumbing was designed for shoppers, not residents.

Change came slowly, like the leaves turning. The displays, the selections of food and other goods all looked the same for a few days. Then I saw a notice to shoppers: “The pharmacy will close Aug. 31.” A couple days later, I picked the last loaf of my favorite rye bread from a shelf, and Jewish rye never returned.

On Sept. 5, the flower stand closed. On Sept. 7, bacon was no more, while birthday cards were at 50% off. Fresh fish and seafood had disappeared. Cat food remained in abundance.

I assumed the goods would remain on the aisles where they had been located for years until everything sold. This is not how professional liquidation is done. The stockers, at night perhaps as I never saw them in action, began consolidating goods on aisles toward the center of the store. So the beans wound up with the salad dressing and olive oil. The checkers no longer knew where to send people to find items. “Nobody tells us anything,” a checker told me. “I tell customers where the cat food used to be.”

She went on to explain that Safeway management had been very good about finding jobs at other stores for the employees. Her colleagues told me the same thing. “They really were concerned about placing us,” said one.

Sign wavers began appearing at the edge of the Safeway parking lot bearing tall signs that read “Total Inventory Blowout.” I love signs like these — they are a testament to American abundance. The Russians lost the Cold War in part because they were incapable of a “Total Inventory Blowout.” Commie stores had so little. I once visited a Warsaw “supermarket” that had a single product — bottles of vinegar.

I asked one of the sign wavers about the job. “I am glad to do it — the money, but this is not a real job. I have to get a real job.” He said he was paid $10 an hour for four hours a day. I told him “You’re not getting enough” and gave him five bucks, a tip.

By Sept. 13, there was no fresh chicken and heavy discounts were in place. In the liquor store, a man and his wife, both short, chunky, of uncertain age, properly masked, bought several shopping carts full of wine and liquor. The guy put $1,300 on his credit card - and the clerk cheerfully told him, he saved $900 with the discount. I wondered, “Is the guy going to drink all that?”

On Sept. 14, I walked in at noon. Almost all the vegetable bins were empty. If you wanted broccoli and carrots, go someplace else. Safeway’s music system was piping in Tommy James' “I Think We’re Alone Now.” I usually don’t expect irony from a supermarket. (...)

A couple days later the liquor, reduced to 50% off, was gone. And there were only three or four aisles left with food. Clearly, some foods had not been sold — they had been removed by stockers. Cheese, for example, disappeared overnight.

On the morning of the last day, I walked down to the store at 7 a.m. I was the only customer. There was salsa, hummus, dried fruit, salad dressing, packaged baby food. Hey, 90% off! I bought a container or hummus and a packet of figs for 95 cents. As I checked out, I told the cashier, “I feel like crying.” She answered “Go ahead; we’ve been crying for weeks.”

Friday, September 25, 2020

Do We Really Need Daily Mail Delivery?

There has been a longstanding interest by various members of Congress and business world to privatize the USPS - allegedly to modernize and improve its service, but in real life because the USPS is a monopoly with enormous profit potential.

“These changes are happening because there’s a White House agenda to privatize and sell off the public Postal Service,” said Mark Dimondstein, president of the American Postal Workers Union. “But there’s too much approval for the organization right now. They want to separate the service from the people and then degrade it to the point where people aren’t going to like it anymore.”

This started back in the Bush administration:

"But the agency has been rapidly losing money since a 2006 law, passed with the support of the George W. Bush administration, required USPS to pre-fund employee retiree health benefits for 75 years in the future. That means the Postal Service must pay for the future health care of employees who have not even been born yet. The burden accounted for an estimated 80% to 90% of the agency’s losses before the pandemic."

Imagine any other business being told to pre-fund health benefits for the next 75 years.

Then this past year the prospect arose that disruption or slowing of the mail service might provide grounds for delegitimizing the results of mail-in ballots in the November election. Some post offices were physically removing mail-sorting machines. The justification (which may well be valid) was that the mix of mail has shifted massively away from letters to packages, and different machines are required for that purpose.

But for this post I'm going to set aside politics and just ask whether daily mail delivery is necessary in this modern era. What prompted me to do this was some interesting items I noticed in the philatelic news:

"News from vanishing postal services are familiar everywhere in these days... In Finland the Post has already dropped Tuesday, and is now planning a three-times per week delivery system. The iconic main Post office at the Helsinki city center was closed this summer, and there are not many post offices left in the city."

"Norway Post will provide every other day delivery of mail due to the decline in mail volume... Recipients will get their mail on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday one week, and Tuesday and Thursday the following week. Those who have a post office box will receive normal daily delivery each weekday... Packages will be delivered every day or every other day depending on where in Norway the household is... Newspapers will be delivered every other day, or daily if the addressee has a post office box."

Those reports were in the March 2020 issue of The Posthorn - Journal of Scandinavian Philately, a publication of the Scandinavian Collector's Club.

via: