Thursday, October 23, 2025

Wednesday, October 22, 2025

Norman Greenbaum

Norman Greenbaum, singer, guitarist, songwriter

Soon after that, I was playing the Troubadour club in LA when the Lovin’ Spoonful’s producer Erik Jacobsen walked in. He said he had a production deal with Warner Brothers and was interested in signing me. When we recorded Spirit in the Sky for my debut album, the finished mix sent shivers up my spine. Initially, Warner said a four-minute single containing lyrics about Jesus would never get played on pop radio, but eventually they relented. In 1969, it sold two million copies. But I couldn’t recreate the success.

In 1986, I was working as a cook when Dr and the Medics took it back to No 1 in the UK. Then Gareth Gates’s 2003 version meant it was No 1 in three different decades. It’s been in countless movies, including Apollo 13, Oceans 11 and Guardians of the Galaxy. I’m 82. A few years ago, I was a passenger in a car crash and spent three weeks in a coma. I feel like I was granted another life. So now every day, I pray and give thanks to the spirit in the sky.

Erik Jacobsen, producer

I saw Norman at a hootenanny at the Troubadour singing one song, School for Sweet Talk, but he said: “I’ve got a million songs I’d love to play for ya.” It turned out he’d had a minor hit called The Eggplant That Ate Chicago with a group called Dr West’s Medicine Show and Junk Band and had a whole raft of crazy songs about goats, chickens or a Chinese guy who ate some acid. I said: “Let’s make some records that somebody might like.”

I put him together with Norman Mayell, the drummer from San Francisco psychedelic group Sopwith Camel, and Doug Killmer, a bassist, who’d played a lot of black music. The Spirit in the Sky riff originated in an old John Lee Hooker tune called Boogie Chillen’ and set the tone for where the song went, but the rhythm track sounded too loose. I got Norman to bring his acoustic guitar in and we recorded two performances – each slightly different – and made it stereo. Then we brought in gospel singers the Stovall Singers and their church-type clapping became a key part of the groove. A guitarist called Russell DaShiell played a hell of a solo. By now, the track was sounding immense, but when I heard Norman’s little vocal, my heart sank. It just wasn’t heavy enough, so once again I recorded two performances and combined the two together. I thought: “Thank God!” It sounded amazing. (...)

The funny thing is that when we went in to record it, my engineer was sick but we went ahead anyway with just a handful of little mics, no headphones and no sound baffling. Every sound was coming in on every mic, but it sounded great. For years people asked: “How in the world did you get that sound?” I said: “I just pointed the amps right at the drums. I had no idea what I was doing.”

[ed. I think Norman (Iron Butterfly and Jimi) did more to invent the term "heavy" back in the late-60s than anybody else - along with this new thing called a fuzz box. See also: The Uncool by Cameron Crowe - Inside Rock's Wildest Decade (Guardian).]

Spirit in the Sky started as an old blues riff I’d been playing since my college days in Boston, but I didn’t know what to do with it. After I moved to LA, a guy I knew came up with a way of putting a fuzzbox inside my Fender Telecaster, which created the distinctive sound on Spirit in the Sky.

I’d come across a greeting card with a picture of some Native Americans praying to the “spirit in the sky”. The phrase stuck in my head. One night I was watching country music on TV and the singer Porter Wagoner sang a gospel song, which gave me the idea to write religious lyrics. Although I came from a semi-religious Jewish family, I wasn’t religious, but found myself writing Christian lyrics such as “When I die and they lay me to rest, I’m going to the place that’s the best” and “Gotta have a friend in Jesus”. It came together very quickly. I survived a car crash and now give thanks to the spirit every day

I’d come across a greeting card with a picture of some Native Americans praying to the “spirit in the sky”. The phrase stuck in my head. One night I was watching country music on TV and the singer Porter Wagoner sang a gospel song, which gave me the idea to write religious lyrics. Although I came from a semi-religious Jewish family, I wasn’t religious, but found myself writing Christian lyrics such as “When I die and they lay me to rest, I’m going to the place that’s the best” and “Gotta have a friend in Jesus”. It came together very quickly. I survived a car crash and now give thanks to the spirit every day

Soon after that, I was playing the Troubadour club in LA when the Lovin’ Spoonful’s producer Erik Jacobsen walked in. He said he had a production deal with Warner Brothers and was interested in signing me. When we recorded Spirit in the Sky for my debut album, the finished mix sent shivers up my spine. Initially, Warner said a four-minute single containing lyrics about Jesus would never get played on pop radio, but eventually they relented. In 1969, it sold two million copies. But I couldn’t recreate the success.

In 1986, I was working as a cook when Dr and the Medics took it back to No 1 in the UK. Then Gareth Gates’s 2003 version meant it was No 1 in three different decades. It’s been in countless movies, including Apollo 13, Oceans 11 and Guardians of the Galaxy. I’m 82. A few years ago, I was a passenger in a car crash and spent three weeks in a coma. I feel like I was granted another life. So now every day, I pray and give thanks to the spirit in the sky.

Erik Jacobsen, producer

I saw Norman at a hootenanny at the Troubadour singing one song, School for Sweet Talk, but he said: “I’ve got a million songs I’d love to play for ya.” It turned out he’d had a minor hit called The Eggplant That Ate Chicago with a group called Dr West’s Medicine Show and Junk Band and had a whole raft of crazy songs about goats, chickens or a Chinese guy who ate some acid. I said: “Let’s make some records that somebody might like.”

I put him together with Norman Mayell, the drummer from San Francisco psychedelic group Sopwith Camel, and Doug Killmer, a bassist, who’d played a lot of black music. The Spirit in the Sky riff originated in an old John Lee Hooker tune called Boogie Chillen’ and set the tone for where the song went, but the rhythm track sounded too loose. I got Norman to bring his acoustic guitar in and we recorded two performances – each slightly different – and made it stereo. Then we brought in gospel singers the Stovall Singers and their church-type clapping became a key part of the groove. A guitarist called Russell DaShiell played a hell of a solo. By now, the track was sounding immense, but when I heard Norman’s little vocal, my heart sank. It just wasn’t heavy enough, so once again I recorded two performances and combined the two together. I thought: “Thank God!” It sounded amazing. (...)

The funny thing is that when we went in to record it, my engineer was sick but we went ahead anyway with just a handful of little mics, no headphones and no sound baffling. Every sound was coming in on every mic, but it sounded great. For years people asked: “How in the world did you get that sound?” I said: “I just pointed the amps right at the drums. I had no idea what I was doing.”

by Dave Simpson, The Guardian | Read more:

Image: Henry Diltz/Corbis/Getty Images[ed. I think Norman (Iron Butterfly and Jimi) did more to invent the term "heavy" back in the late-60s than anybody else - along with this new thing called a fuzz box. See also: The Uncool by Cameron Crowe - Inside Rock's Wildest Decade (Guardian).]

Tuesday, October 21, 2025

The Shadow President

On the afternoon of Feb. 12, Russell Vought, the director of the White House Office of Management and Budget, summoned a small group of career staffers to the Eisenhower Executive Office Building for a meeting about foreign aid. A storm had dumped nearly 6 inches of snow on Washington, D.C. The rest of the federal government was running on a two-hour delay, but Vought had offered his team no such reprieve. As they filed into a second-floor conference room decorated with photos of past OMB directors, Vought took his seat at the center of a worn wooden table and laid his briefing materials out before him.

Vought, a bookish technocrat with an encyclopedic knowledge of the inner workings of the U.S. government, cuts an unusual figure in Trump’s inner circle of Fox News hosts and right-wing influencers. He speaks in a flat, nasally monotone and, with his tortoiseshell glasses, standard-issue blue suits and corona of close-cropped hair, most resembles what he claims to despise: a federal bureaucrat. The Office of Management and Budget, like Vought himself, is little known outside the Beltway and poorly understood even among political insiders. What it lacks in cachet, however, it makes up for in the vast influence it wields across the government. Samuel Bagenstos, an OMB general counsel during the Biden administration, told me, “Every goddam thing in the executive branch goes through OMB.”

The OMB reviews all significant regulations proposed by individual agencies. It vets executive orders before the president signs them. It issues workforce policies for more than 2 million federal employees. Most notably, every penny appropriated by Congress is dispensed by the OMB, making the agency a potential choke point in a federal bureaucracy that currently spends about $7 trillion a year. Shalanda Young, Vought’s predecessor, told me, “If you’re OK with your name not being in the spotlight and just getting stuff done,” then directing the OMB “can be one of the most powerful jobs in D.C.”

During Donald Trump’s first term, Vought (whose name is pronounced “vote”) did more than perhaps anyone else to turn the president’s demands and personal grievances into government action. In 2019, after Congress refused to fund Trump’s border wall, Vought, then the acting director of the OMB, redirected billions of dollars in Department of Defense money to build it. Later that year, after the Trump White House pressured Ukraine’s government to investigate Joe Biden, who was running for president, Vought froze $214 million in security assistance for Ukraine. “The president loved Russ because he could count on him,” Mark Paoletta, who has served as the OMB general counsel in both Trump administrations, said at a conservative policy summit in 2022, according to a recording I obtained. “He wasn’t a showboat, and he was committed to doing what the president wanted to do.”

After the pro-Trump riots at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, many Republicans, including top administration officials, disavowed the president. Vought remained loyal. He echoed Trump’s baseless claims about election fraud and publicly defended people who were arrested for their participation in the melee. During the Biden years, Vought labored to translate the lessons of Trump’s tumultuous first term into a more effective second presidency. He chaired the transition portion of Project 2025, a joint effort by a coalition of conservative groups to develop a road map for the next Republican administration, helping to draft some 350 executive orders, regulations and other plans to more fully empower the president. “Despite his best thinking and the aggressive things they tried in Trump One, nothing really stuck,” a former OMB branch chief who served under Vought during the first Trump administration told me. “Most administrations don’t get a four-year pause or have the chance to think about ‘Why isn’t this working?’” The former branch chief added, “Now he gets to come back and steamroll everyone.”

At the meeting in February, according to people familiar with the events, Vought’s directive was simple: slash foreign assistance to the greatest extent possible. The U.S. government shouldn’t support overseas anti-malaria initiatives, he argued, because buying mosquito nets doesn’t make Americans safer or more prosperous. He questioned why the U.S. funded an international vaccine alliance, given the anti-vaccine views of Trump’s nominee for secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. The conversation turned to the United States Institute of Peace, a government-funded nonprofit created under Ronald Reagan, which worked to prevent conflicts overseas; Vought asked what options existed to eliminate it. When he was told that the USIP was funded by Congress and legally independent, he replied, “We’ll see what we can do.” (A few days later, Trump signed an executive order that directed the OMB to dismantle the organization.)

The OMB staffers had tried to anticipate Vought’s desired outcome for more than $7 billion that the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development spent each year on humanitarian assistance, including disaster relief and support for refugees and conflict victims. During the campaign, Trump had vowed to defund agencies that give money to people “who have no respect for us at all,” and Project 2025 had accused USAID of pursuing a “divisive political and cultural agenda.” The staffers proposed a cut of 50%.

Vought was unsatisfied. What would be the consequences, he asked, of a much larger reduction? A career official answered: Less humanitarian aid would mean more people would die. “You could say that about any of these cuts,” Vought replied. A person familiar with the meeting described his reaction as “blasé.” Vought reiterated that he wanted spending on foreign aid to be as close to zero as possible, on the fastest timeline possible. Several analysts left the meeting rattled. Word of what had happened spread quickly among the OMB staff. Another person familiar with the meeting later told me, “It was the day that broke me.”

What Vought has done in the nine months since Trump took office goes much further than slashing foreign aid. Relying on an expansive theory of presidential power and a willingness to test the rule of law, he has frozen vast sums of federal spending, terminated tens of thousands of federal workers and, in a few cases, brought entire agencies to a standstill. In early October, after Senate Democrats refused to vote for a budget resolution without additional health care protections, effectively shutting down the government, Vought became the face of the White House’s response. On the second day of the closure, Trump shared an AI-generated video that depicted his budget director — who, by then, had threatened mass firings across the federal workforce and paused or canceled $26 billion in funding for infrastructure and clean-energy projects in blue states — as the Grim Reaper of Washington, D.C. “We work for the president of the United States,” a senior agency official who regularly deals with the OMB told me. But right now “it feels like we work for Russ Vought. He has centralized decision-making power to an extent that he is the commander in chief.”

[ed. It wasn't as if Republicans in Congress had any illusions about Vought and his agenda when they confirmed him for the OMB job. Except one: miscalculating how quickly they'd become roadkill themselves. See also: What You Should Know About Russ Vought, Trump’s Shadow President.]

Vought, a bookish technocrat with an encyclopedic knowledge of the inner workings of the U.S. government, cuts an unusual figure in Trump’s inner circle of Fox News hosts and right-wing influencers. He speaks in a flat, nasally monotone and, with his tortoiseshell glasses, standard-issue blue suits and corona of close-cropped hair, most resembles what he claims to despise: a federal bureaucrat. The Office of Management and Budget, like Vought himself, is little known outside the Beltway and poorly understood even among political insiders. What it lacks in cachet, however, it makes up for in the vast influence it wields across the government. Samuel Bagenstos, an OMB general counsel during the Biden administration, told me, “Every goddam thing in the executive branch goes through OMB.”

The OMB reviews all significant regulations proposed by individual agencies. It vets executive orders before the president signs them. It issues workforce policies for more than 2 million federal employees. Most notably, every penny appropriated by Congress is dispensed by the OMB, making the agency a potential choke point in a federal bureaucracy that currently spends about $7 trillion a year. Shalanda Young, Vought’s predecessor, told me, “If you’re OK with your name not being in the spotlight and just getting stuff done,” then directing the OMB “can be one of the most powerful jobs in D.C.”

During Donald Trump’s first term, Vought (whose name is pronounced “vote”) did more than perhaps anyone else to turn the president’s demands and personal grievances into government action. In 2019, after Congress refused to fund Trump’s border wall, Vought, then the acting director of the OMB, redirected billions of dollars in Department of Defense money to build it. Later that year, after the Trump White House pressured Ukraine’s government to investigate Joe Biden, who was running for president, Vought froze $214 million in security assistance for Ukraine. “The president loved Russ because he could count on him,” Mark Paoletta, who has served as the OMB general counsel in both Trump administrations, said at a conservative policy summit in 2022, according to a recording I obtained. “He wasn’t a showboat, and he was committed to doing what the president wanted to do.”

After the pro-Trump riots at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, many Republicans, including top administration officials, disavowed the president. Vought remained loyal. He echoed Trump’s baseless claims about election fraud and publicly defended people who were arrested for their participation in the melee. During the Biden years, Vought labored to translate the lessons of Trump’s tumultuous first term into a more effective second presidency. He chaired the transition portion of Project 2025, a joint effort by a coalition of conservative groups to develop a road map for the next Republican administration, helping to draft some 350 executive orders, regulations and other plans to more fully empower the president. “Despite his best thinking and the aggressive things they tried in Trump One, nothing really stuck,” a former OMB branch chief who served under Vought during the first Trump administration told me. “Most administrations don’t get a four-year pause or have the chance to think about ‘Why isn’t this working?’” The former branch chief added, “Now he gets to come back and steamroll everyone.”

At the meeting in February, according to people familiar with the events, Vought’s directive was simple: slash foreign assistance to the greatest extent possible. The U.S. government shouldn’t support overseas anti-malaria initiatives, he argued, because buying mosquito nets doesn’t make Americans safer or more prosperous. He questioned why the U.S. funded an international vaccine alliance, given the anti-vaccine views of Trump’s nominee for secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. The conversation turned to the United States Institute of Peace, a government-funded nonprofit created under Ronald Reagan, which worked to prevent conflicts overseas; Vought asked what options existed to eliminate it. When he was told that the USIP was funded by Congress and legally independent, he replied, “We’ll see what we can do.” (A few days later, Trump signed an executive order that directed the OMB to dismantle the organization.)

The OMB staffers had tried to anticipate Vought’s desired outcome for more than $7 billion that the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development spent each year on humanitarian assistance, including disaster relief and support for refugees and conflict victims. During the campaign, Trump had vowed to defund agencies that give money to people “who have no respect for us at all,” and Project 2025 had accused USAID of pursuing a “divisive political and cultural agenda.” The staffers proposed a cut of 50%.

Vought was unsatisfied. What would be the consequences, he asked, of a much larger reduction? A career official answered: Less humanitarian aid would mean more people would die. “You could say that about any of these cuts,” Vought replied. A person familiar with the meeting described his reaction as “blasé.” Vought reiterated that he wanted spending on foreign aid to be as close to zero as possible, on the fastest timeline possible. Several analysts left the meeting rattled. Word of what had happened spread quickly among the OMB staff. Another person familiar with the meeting later told me, “It was the day that broke me.”

What Vought has done in the nine months since Trump took office goes much further than slashing foreign aid. Relying on an expansive theory of presidential power and a willingness to test the rule of law, he has frozen vast sums of federal spending, terminated tens of thousands of federal workers and, in a few cases, brought entire agencies to a standstill. In early October, after Senate Democrats refused to vote for a budget resolution without additional health care protections, effectively shutting down the government, Vought became the face of the White House’s response. On the second day of the closure, Trump shared an AI-generated video that depicted his budget director — who, by then, had threatened mass firings across the federal workforce and paused or canceled $26 billion in funding for infrastructure and clean-energy projects in blue states — as the Grim Reaper of Washington, D.C. “We work for the president of the United States,” a senior agency official who regularly deals with the OMB told me. But right now “it feels like we work for Russ Vought. He has centralized decision-making power to an extent that he is the commander in chief.”

by Andy Kroll, Pro Publica | Read more:

Image: Evan Vucci/AP[ed. It wasn't as if Republicans in Congress had any illusions about Vought and his agenda when they confirmed him for the OMB job. Except one: miscalculating how quickly they'd become roadkill themselves. See also: What You Should Know About Russ Vought, Trump’s Shadow President.]

China Has Overtaken America

In 1957 the Soviet Union put the first man-made satellite — Sputnik — into orbit. The U.S. response was close to panic: The Cold War was at its coldest, and there were widespread fears that the Soviets were taking the lead in science and technology.

In retrospect those fears were overblown. When Communism fell, we learned that the Soviet economy was far less advanced than many had believed. Still, the effects of the “Sputnik moment” were salutary: America poured resources into science and higher education, helping to lay the foundations for enduring leadership.

Today American leadership is once again being challenged by an authoritarian regime. And in terms of economic might, China is a much more serious rival than the Soviet Union ever was. Some readers were skeptical when I pointed out Monday that China’s economy is, in real terms, already substantially larger than ours. The truth is that GDP at purchasing power parity is a very useful measure, but if it seems too technical, how about just looking at electricity generation, which is strongly correlated with economic development? As the chart at the top of this post shows, China now generates well over twice as much electricity as we do.

Yet, rather than having another Sputnik moment, we are now trapped in a reverse Sputnik moment. Rather than acknowledging that the US is in danger of being permanently overtaken by China’s technological and economic prowess, the Trump administration is slashing support for scientific research and attacking education. In the name of defeating the bogeymen of “wokeness” and the “deep state”, this administration is actively opposing progress in critical sectors while giving grifters like the crypto industry everything that they want.

The most obvious example of Trump’s war on a critical sector, and the most consequential for the next decade, is his vendetta against renewable energy. Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill rolled back Biden’s tax incentives for renewable energy. The administration is currently trying to kill a huge, nearly completed offshore wind farm that could power hundreds of thousands of homes, as well as cancel $7 billion in grants for residential solar panels. It appears to have succeeded in killing a huge solar energy project that would have powered almost 2 million homes. It has canceled $8 billion in clean energy grants, mostly in Democratic states, and is reportedly planning to cancel tens of billions more. (...)

In his rambling speech at the United Nations, Donald Trump insisted that China isn’t making use of wind power: “They use coal, they use gas, they use almost anything, but they don’t like wind.” I don’t know where Trump gets his misinformation — maybe the same sources telling him that Portland is in flames. But here’s the reality:

Special interests and Trump’s pettiness aside, my sense is that there’s something more visceral going on. A powerful faction in America has become deeply hostile to science and to expertise in general. As evidence, consider the extraordinary collapse in Republican support for higher education over the past decade:

In retrospect those fears were overblown. When Communism fell, we learned that the Soviet economy was far less advanced than many had believed. Still, the effects of the “Sputnik moment” were salutary: America poured resources into science and higher education, helping to lay the foundations for enduring leadership.

Today American leadership is once again being challenged by an authoritarian regime. And in terms of economic might, China is a much more serious rival than the Soviet Union ever was. Some readers were skeptical when I pointed out Monday that China’s economy is, in real terms, already substantially larger than ours. The truth is that GDP at purchasing power parity is a very useful measure, but if it seems too technical, how about just looking at electricity generation, which is strongly correlated with economic development? As the chart at the top of this post shows, China now generates well over twice as much electricity as we do.

Yet, rather than having another Sputnik moment, we are now trapped in a reverse Sputnik moment. Rather than acknowledging that the US is in danger of being permanently overtaken by China’s technological and economic prowess, the Trump administration is slashing support for scientific research and attacking education. In the name of defeating the bogeymen of “wokeness” and the “deep state”, this administration is actively opposing progress in critical sectors while giving grifters like the crypto industry everything that they want.

The most obvious example of Trump’s war on a critical sector, and the most consequential for the next decade, is his vendetta against renewable energy. Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill rolled back Biden’s tax incentives for renewable energy. The administration is currently trying to kill a huge, nearly completed offshore wind farm that could power hundreds of thousands of homes, as well as cancel $7 billion in grants for residential solar panels. It appears to have succeeded in killing a huge solar energy project that would have powered almost 2 million homes. It has canceled $8 billion in clean energy grants, mostly in Democratic states, and is reportedly planning to cancel tens of billions more. (...)

In his rambling speech at the United Nations, Donald Trump insisted that China isn’t making use of wind power: “They use coal, they use gas, they use almost anything, but they don’t like wind.” I don’t know where Trump gets his misinformation — maybe the same sources telling him that Portland is in flames. But here’s the reality:

Chris Wright, Trump’s energy secretary, says that solar power is unreliable: “You have to have power when the sun goes behind a cloud and when the sun sets, which it does almost every night.” So the energy secretary of the most technologically advanced nation on earth is unaware of the energy revolution being propelled by dramatic technological progress in batteries. And the revolution is happening now in the U.S., in places like California. Here’s what electricity supply looked like during an average day in California back in June:

Special interests and Trump’s pettiness aside, my sense is that there’s something more visceral going on. A powerful faction in America has become deeply hostile to science and to expertise in general. As evidence, consider the extraordinary collapse in Republican support for higher education over the past decade:

Yet the truth is that hostility to science and expertise have always been part of the American tradition. Remember your history lesson on the Scopes Monkey Trial? It took a Supreme Court ruling, as recently as 2007, to stop politicians from forcing public schools to teach creationism. And with the current Supreme Court, who can be sure creationism won’t return?

Anti-scientism is a widespread attitude on the religious right, which forms a key component of MAGA. In past decades, however, the forces of humanism and scientific inquiry were able to prevail against anti-scientism. In part this was due to the recognition that American science was essential for national security as well as national prosperity. But now we have an administration that claims to be protecting national security by imposing tariffs on kitchen cabinets and bathroom vanities, while gutting the CDC and the EPA.

Does this mean that the U.S. is losing the race with China for global leadership? No, I think that race is essentially over. Even if Trump and his team of saboteurs lose power in 2028, everything I see says that by then America will have fallen so far behind that it’s unlikely that we will ever catch up.

Anti-scientism is a widespread attitude on the religious right, which forms a key component of MAGA. In past decades, however, the forces of humanism and scientific inquiry were able to prevail against anti-scientism. In part this was due to the recognition that American science was essential for national security as well as national prosperity. But now we have an administration that claims to be protecting national security by imposing tariffs on kitchen cabinets and bathroom vanities, while gutting the CDC and the EPA.

Does this mean that the U.S. is losing the race with China for global leadership? No, I think that race is essentially over. Even if Trump and his team of saboteurs lose power in 2028, everything I see says that by then America will have fallen so far behind that it’s unlikely that we will ever catch up.

by Paul Krugman | Read more:

Images: OurWorldInData/FT

[ed. See also: Losing Touch With Reality; Civil Resistance Confronts the Autocracy; and, An Autocracy of Dunces (Krugman).]

Labels:

Business,

Environment,

Government,

Politics,

Science,

Technology

Microplastics Are Everywhere

You can do one simple thing to avoid them.

If you are concerned about microplastics, the world starts to look like a minefield. The tiny particles can slough off polyester clothing and swirl around in the air inside your home; they can scrape off of food packaging into your take-out food.

But as scientists zero in on the sources of microplastics — and how they get into human bodies — one factor stands out.

Microplastics, studies increasingly show, are released from exposure to heat.

“Heat probably plays the most crucial role in generating these micro- and nanoplastics,” said Kazi Albab Hussain, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln.

Pour coffee into a plastic foam cup, and pieces of the cup will leach out into the coffee itself. Brew tea, and millions of microplastics and even tinier nanoplastics will spill from the tea bag into your cup. Wash your polyester clothing on high heat, and the textiles can start to break apart, sending microplastics spinning through the water supply.

In one recent study by researchers at the University of Birmingham in England, scientists analyzed 31 beverages for sale on the British market — from fruit juices and sodas to coffee and tea. They looked at particles bigger than 10 micrometers in diameter, or roughly one-fifth the width of a human hair. While all the drinks had at least a dozen microplastic particles in them on average, by far the highest numbers were in hot drinks. Hot tea, for example, had an average of 60 particles per liter, while iced tea had 31 particles. Hot coffee had 43 particles per liter, while iced coffee had closer to 37.

These particles, according to Mohamed Abdallah, a professor of geography and emerging contaminants at the university and one of the authors of the study, are coming from a range of sources — the plastic lid on a to-go cup of coffee, the small bits of plastic lining a tea bag. But when hot water is added to the mix, the rate of microplastic release increases.

“Heat makes it easier for microplastics to leach out from packaging materials,” Abdallah said.

The effect was even stronger in plastics that are older and degraded. Hot coffee prepared in an eight-year-old home coffee machine with plastic components had twice as many microplastics as coffee prepared in a machine that was only six months old.

Other research has found the same results with even smaller nanoplastics, defined as plastic particles less than one micrometer in diameter.

Scientists at the University of Nebraska, including Hussain, analyzed small plastic jars and tubs used for storing baby food and found that the containers could release more than 2 billion nanoplastics per square centimeter when heated in the microwave — significantly more than when stored at room temperature or in a refrigerator.

The same effect has been shown in studies looking at how laundry produces microplastics: Higher washing temperatures, scientists have found, lead to more tiny plastics released from synthetic clothing.

Heat, Hussain explained, is simply bad for plastic, especially plastic used to store food and drinks.

by Shannon Osaka, Washington Post | Read more:

But as scientists zero in on the sources of microplastics — and how they get into human bodies — one factor stands out.

Microplastics, studies increasingly show, are released from exposure to heat.

“Heat probably plays the most crucial role in generating these micro- and nanoplastics,” said Kazi Albab Hussain, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln.

Pour coffee into a plastic foam cup, and pieces of the cup will leach out into the coffee itself. Brew tea, and millions of microplastics and even tinier nanoplastics will spill from the tea bag into your cup. Wash your polyester clothing on high heat, and the textiles can start to break apart, sending microplastics spinning through the water supply.

In one recent study by researchers at the University of Birmingham in England, scientists analyzed 31 beverages for sale on the British market — from fruit juices and sodas to coffee and tea. They looked at particles bigger than 10 micrometers in diameter, or roughly one-fifth the width of a human hair. While all the drinks had at least a dozen microplastic particles in them on average, by far the highest numbers were in hot drinks. Hot tea, for example, had an average of 60 particles per liter, while iced tea had 31 particles. Hot coffee had 43 particles per liter, while iced coffee had closer to 37.

These particles, according to Mohamed Abdallah, a professor of geography and emerging contaminants at the university and one of the authors of the study, are coming from a range of sources — the plastic lid on a to-go cup of coffee, the small bits of plastic lining a tea bag. But when hot water is added to the mix, the rate of microplastic release increases.

“Heat makes it easier for microplastics to leach out from packaging materials,” Abdallah said.

The effect was even stronger in plastics that are older and degraded. Hot coffee prepared in an eight-year-old home coffee machine with plastic components had twice as many microplastics as coffee prepared in a machine that was only six months old.

Other research has found the same results with even smaller nanoplastics, defined as plastic particles less than one micrometer in diameter.

Scientists at the University of Nebraska, including Hussain, analyzed small plastic jars and tubs used for storing baby food and found that the containers could release more than 2 billion nanoplastics per square centimeter when heated in the microwave — significantly more than when stored at room temperature or in a refrigerator.

The same effect has been shown in studies looking at how laundry produces microplastics: Higher washing temperatures, scientists have found, lead to more tiny plastics released from synthetic clothing.

Heat, Hussain explained, is simply bad for plastic, especially plastic used to store food and drinks.

by Shannon Osaka, Washington Post | Read more:

Image: Yaroslav Litun/iStock

Monday, October 20, 2025

The Team That Makes Mariners Games More Fun

Inside the Mariners control room at T-Mobile Park on Friday afternoon, more than a dozen staff members operating cameras, video screens and soundboards were united by a single mission: Craft a unique, rallying gameday experience with the M’s backed against a wall.

The Mariners and their fans needed a comeback. After losing Games 3 and 4 of the American League Championship Series in Seattle this week, the chance to clinch a first-ever World Series berth at T-Mobile Park had slipped away. Now, headed into Game 5 against the Toronto Blue Jays, the control room was preparing for the last guaranteed baseball game in the Emerald City this season.

(The ALCS heads back to Ontario to finish out the series on Sunday for Game 6 and Monday for a winner-take-all Game 7, if necessary.) [ed. Necessary. Tonight's the night!]

[ed. See also: Words (and Stats) Struggle to Capture Shohei Ohtani’s GOAT Game (Ringer).]

For one night, we marveled anew at perhaps the most impressive player in baseball history, as he produced perhaps the most impressive postseason game in baseball history. And for one night, Ohtani seemed less like a means to the Dodgers’ success than the Dodgers seemed like a means to Ohtani’s.

The Mariners and their fans needed a comeback. After losing Games 3 and 4 of the American League Championship Series in Seattle this week, the chance to clinch a first-ever World Series berth at T-Mobile Park had slipped away. Now, headed into Game 5 against the Toronto Blue Jays, the control room was preparing for the last guaranteed baseball game in the Emerald City this season.

(The ALCS heads back to Ontario to finish out the series on Sunday for Game 6 and Monday for a winner-take-all Game 7, if necessary.) [ed. Necessary. Tonight's the night!]

So how do you get a sellout crowd of M’s fans onto their feet and cheering like there’s no tomorrow? And how do you keep folks excited and smiling for nine innings (or more) when the games can be so stressful that smartwatches send out cardio warnings?

“Ultimately it’s just knowing the fans, knowing the team and knowing your content,” said Nicholas Sybouts, coordinator of game entertainment for the Mariners.

Three hours before first pitch on Friday, Sybouts and Tyler Thompson, the Mariners’ director of game entertainment and experiential marketing, were poring over a thick stack of papers that detailed the schedule for the game. Not the baseball itself, mind you. Each minute of the game off the field is carefully orchestrated, from the ceremonial first pitch to the team’s famous salmon run and late-game rally videos.

Thompson said well-timed rally videos — featuring everything from breathing exercises to sea shanties and the fan-favorite Windows desktop crash screen — have been winning strategies for reviving the crowd this season at T-Mobile Park. A good idea can come from anywhere, Sybouts said. He and Thompson create a storyboard for each video before sending it to a team of motion graphic animators to bring the idea to life.

The team creates so many ideas, in fact, that they have filled up an entire binder that’s divided into subgroups that reflect the tone of the game.

“You don’t want to play a cute otter video when the team is down,” Sybouts said.

Half of the entries are highlighted green, which means they were added for the postseason. Control room operators Edward Cunningham and Zachary McHugh are in charge of queuing up each video onto the ballpark’s enormous video board.

“We’ve been rolling out some new ones,” Cunningham said. One of them, dubbed the “horror rally,” quotes a sound bite from the Texas Rangers broadcast booth, which called T-Mobile Park “a nightmare” for opposing teams.

Running the scoreboard is no walk in the park. The team reacts in real time and efficiently communicates with each other to line up videos that fit the tone of any given moment in a game.

“In baseball, anything can happen,” Cunningham said. “So, it kind of keeps us on our toes a lot.”

Throughout a season, about 2.5 million fans come through the ballpark, Sybouts said. Being able to serve sold-out crowds during the postseason has been special, said Sybouts, who was born in Yakima and is a lifelong Mariners fan.

“People are doing so much to be here,” he said. “They’re finding tickets, they’re taking time off work. So many people’s lives are invested in Mariners baseball right now, and it means the world that we could help create unforgettable experiences for them.”

by Nicole Pasia, Seattle Times | Read more:

Images: Ivy Ceballo

“Ultimately it’s just knowing the fans, knowing the team and knowing your content,” said Nicholas Sybouts, coordinator of game entertainment for the Mariners.

Three hours before first pitch on Friday, Sybouts and Tyler Thompson, the Mariners’ director of game entertainment and experiential marketing, were poring over a thick stack of papers that detailed the schedule for the game. Not the baseball itself, mind you. Each minute of the game off the field is carefully orchestrated, from the ceremonial first pitch to the team’s famous salmon run and late-game rally videos.

Thompson said well-timed rally videos — featuring everything from breathing exercises to sea shanties and the fan-favorite Windows desktop crash screen — have been winning strategies for reviving the crowd this season at T-Mobile Park. A good idea can come from anywhere, Sybouts said. He and Thompson create a storyboard for each video before sending it to a team of motion graphic animators to bring the idea to life.

The team creates so many ideas, in fact, that they have filled up an entire binder that’s divided into subgroups that reflect the tone of the game.

“You don’t want to play a cute otter video when the team is down,” Sybouts said.

Half of the entries are highlighted green, which means they were added for the postseason. Control room operators Edward Cunningham and Zachary McHugh are in charge of queuing up each video onto the ballpark’s enormous video board.

“We’ve been rolling out some new ones,” Cunningham said. One of them, dubbed the “horror rally,” quotes a sound bite from the Texas Rangers broadcast booth, which called T-Mobile Park “a nightmare” for opposing teams.

Running the scoreboard is no walk in the park. The team reacts in real time and efficiently communicates with each other to line up videos that fit the tone of any given moment in a game.

“In baseball, anything can happen,” Cunningham said. “So, it kind of keeps us on our toes a lot.”

Throughout a season, about 2.5 million fans come through the ballpark, Sybouts said. Being able to serve sold-out crowds during the postseason has been special, said Sybouts, who was born in Yakima and is a lifelong Mariners fan.

“People are doing so much to be here,” he said. “They’re finding tickets, they’re taking time off work. So many people’s lives are invested in Mariners baseball right now, and it means the world that we could help create unforgettable experiences for them.”

by Nicole Pasia, Seattle Times | Read more:

Images: Ivy Ceballo

[ed. Historic night tonight. Go Ms! Update: Not to be, unfortunately... oh well, still a great, great season, just two runs short. Toronto now gets to face this guy: Shohei Ohtani just played the greatest game in baseball history (WSJ):]

This is Beethoven at a piano. This is Shakespeare with a quill. This is Michael Jordan in the Finals. This is Tiger Woods in Sunday red.

This is too good to be true with no reason to doubt it. This is the beginning of every baseball conversation and the end of the debate: Shohei Ohtani is the best baseball player who has ever played the game, the most talented hitter and pitcher of an era in which data and nutrition have made an everyman’s sport a game for superhumans. And Friday night, when he helped his Los Angeles Dodgers win the pennant with a 5-1 victory over the Milwaukee Brewers in Game 4 of the National League Championship Series, was his Mona Lisa.

This is Beethoven at a piano. This is Shakespeare with a quill. This is Michael Jordan in the Finals. This is Tiger Woods in Sunday red.

This is too good to be true with no reason to doubt it. This is the beginning of every baseball conversation and the end of the debate: Shohei Ohtani is the best baseball player who has ever played the game, the most talented hitter and pitcher of an era in which data and nutrition have made an everyman’s sport a game for superhumans. And Friday night, when he helped his Los Angeles Dodgers win the pennant with a 5-1 victory over the Milwaukee Brewers in Game 4 of the National League Championship Series, was his Mona Lisa.

[ed. See also: Words (and Stats) Struggle to Capture Shohei Ohtani’s GOAT Game (Ringer).]

For one night, we marveled anew at perhaps the most impressive player in baseball history, as he produced perhaps the most impressive postseason game in baseball history. And for one night, Ohtani seemed less like a means to the Dodgers’ success than the Dodgers seemed like a means to Ohtani’s.

My Last Day as an Accomplice of the Republican Party

Since Donald Trump descended that golden escalator in 2015, the Republican party has devolved into a cult of personality that mirrors the worst authoritarian regimes of the last one hundred years.

For ten years, the GOP has waged an unrelenting war on our civic institutions, the separation of powers, the foundation of the rule of law, and the very nature of truth itself. While Trump and his supporters in Congress have been the driving force behind the right’s descent into despotism, it would not have been possible without the thousands of consultants, aides, and politicos working behind the scenes to fully execute their systematic dismantling of American democratic norms.

That’s why I’m publishing this letter today.

For over twelve years, I worked inside the Republican ecosystem, helping the party advance its goals in several fields, ranging from grassroots voter outreach to digital fundraising. I worked inside GOP circles through Trump’s takeover of the party, his initial downfall, and his resurgence in 2023–2024. At every step along the way, I rationalized, compartmentalized, and found excuses to stay tethered to the party, even as I grew to believe it was undermining the foundations of our constitutional republic. But over the last few months, the compartmentalization and coping stopped working to silence my conscience.

And now, after more than a decade, I have decided I have finally had enough.

I quit. I quit the Republican party and my job as an accomplice to the party in the throes of an authoritarian cult. Today, I resigned from my career as a senior fundraising strategist for one of the leading Republican digital fundraising firms in Washington, D.C.

I’m not the first to take this path. A lot of ink has been spilled by former Republican politicians and staffers about why they left the Republican party. Tim Miller’s Why We Did It provides a valuable perspective from the vantage point of a political strategist at the Senate and presidential level. My journey has been through the lower tiers of the Republican party, in state-level campaigns and as a mid-level manager in a GOP-affiliated consulting firm. Mine wasn’t as high a vantage point. But when it comes to understanding the MAGA takeover, it was no less critical. It was at this level that I saw firsthand how Trumpism, as both a cultural and political force, took hold at the grassroots level, driving local politicians to make the thousands of decisions and compromises that in turn enabled Trump and GOP leadership to wedge the MAGA movement even deeper into American life.

Don’t get me wrong: My ego is not so large that I believe I played a significant role in putting Trump into office. What I mean is that it took the collective action of thousands of people in similar positions, working nine-to-five jobs, figuring out how they were going to pay for their kid’s daycare or fund their retirement, to get us where we are today. I was a part of that—until I decided I could no longer be.

My goal in quitting the party and writing this piece is twofold: first, to shed light on why someone would continue to work for an increasingly corrupt and authoritarian political party despite their divergent ethical and political beliefs; second, to convince any number of consultants, staffers, and former colleagues to follow their consciences and leave with their integrity still intact.

To do that, I should start by explaining how I arrived at working for the Republican party.

[ed. Probably relevant for others in similar positions unless they figure out how to make serious amends (and a living going forward). They've cast their lots with MAGA, Trump, far-right Nazis, and every other wingnut group in this toxic coalition. Now they have no where else to go outside of the Republican ecosystem. Their words and actions will follow them forever (especially with women who might otherwise have given them a chance). Personally, I'd like to see a Lysistrata rebellion.]

For ten years, the GOP has waged an unrelenting war on our civic institutions, the separation of powers, the foundation of the rule of law, and the very nature of truth itself. While Trump and his supporters in Congress have been the driving force behind the right’s descent into despotism, it would not have been possible without the thousands of consultants, aides, and politicos working behind the scenes to fully execute their systematic dismantling of American democratic norms.

That’s why I’m publishing this letter today.

For over twelve years, I worked inside the Republican ecosystem, helping the party advance its goals in several fields, ranging from grassroots voter outreach to digital fundraising. I worked inside GOP circles through Trump’s takeover of the party, his initial downfall, and his resurgence in 2023–2024. At every step along the way, I rationalized, compartmentalized, and found excuses to stay tethered to the party, even as I grew to believe it was undermining the foundations of our constitutional republic. But over the last few months, the compartmentalization and coping stopped working to silence my conscience.

And now, after more than a decade, I have decided I have finally had enough.

I quit. I quit the Republican party and my job as an accomplice to the party in the throes of an authoritarian cult. Today, I resigned from my career as a senior fundraising strategist for one of the leading Republican digital fundraising firms in Washington, D.C.

I’m not the first to take this path. A lot of ink has been spilled by former Republican politicians and staffers about why they left the Republican party. Tim Miller’s Why We Did It provides a valuable perspective from the vantage point of a political strategist at the Senate and presidential level. My journey has been through the lower tiers of the Republican party, in state-level campaigns and as a mid-level manager in a GOP-affiliated consulting firm. Mine wasn’t as high a vantage point. But when it comes to understanding the MAGA takeover, it was no less critical. It was at this level that I saw firsthand how Trumpism, as both a cultural and political force, took hold at the grassroots level, driving local politicians to make the thousands of decisions and compromises that in turn enabled Trump and GOP leadership to wedge the MAGA movement even deeper into American life.

Don’t get me wrong: My ego is not so large that I believe I played a significant role in putting Trump into office. What I mean is that it took the collective action of thousands of people in similar positions, working nine-to-five jobs, figuring out how they were going to pay for their kid’s daycare or fund their retirement, to get us where we are today. I was a part of that—until I decided I could no longer be.

My goal in quitting the party and writing this piece is twofold: first, to shed light on why someone would continue to work for an increasingly corrupt and authoritarian political party despite their divergent ethical and political beliefs; second, to convince any number of consultants, staffers, and former colleagues to follow their consciences and leave with their integrity still intact.

To do that, I should start by explaining how I arrived at working for the Republican party.

by Miles Bruner, The Bulwark | Read more:

Image: Carl MaynarSunday, October 19, 2025

Gerrymandering - Past, Present, Future

‘I think we’ll get five,’ President Trump said, and five was what he got. At his prompting, the Republican-dominated Texas legislature remapped the districts to be used in next year’s elections to the federal House of Representatives. Their map includes five new seats that are likely to be won by the Republicans, who already hold 25 of the state’s 38 seats. Until this year, the Democrat Al Green’s Ninth Congressional District covered Democrat-leaning south and south-western Houston. Now, it ranges east over Republican-leaning Harris County and Liberty County, with most of the former constituency reallocated to other districts. Green has accused Trump and his allies in Texas of infusing ‘racism into Texas redistricting’ by targeting Black representatives like him and diluting the Black vote. ‘I did not take race into consideration when drawing this map,’ Phil King, the state senator responsible for the redistricting legislation, claimed. ‘I drew it based on what would better perform for Republican candidates.’ His colleague Todd Hunter, who introduced the redistricting bill, agreed. ‘The underlying goal of this plan is straightforward: improve Republican political performance.’

King and Hunter can say these things because there is no judicial remedy for designing a redistricting map that sews up the outcome of a congressional election. In 2019, Chief Justice John Roberts declared that although the Supreme Court ‘does not condone excessive partisan gerrymandering’, any court-mandated intervention in district maps would inevitably look partisan and impugn the court’s neutrality. In 2017, during arguments in a different case, Roberts contrasted the ‘sociological gobbledygook’ of political science on gerrymandering with the formal and objective science of American constitutional law.

‘Sociological gobbledygook’ teaches that the drawing of the boundaries of single-member districts can all but determine the outcome of an election. Imagine a state with twenty blue and thirty red voters that must be sliced into five districts. A map that tracked the overall distribution of votes would have two blue and three red districts. But if you can put six red voters and four blue voters in each of the five boxes, you will end up with five relatively safe red districts. This is known as ‘cracking’ the blue electorate. Or you could create two districts with six blues and one with eight blues, making three safe blue districts by ‘packing’ red supporters – concentrating them in a smaller number of districts. The notion that democratic elections are supposed to allow voters to make a real choice between candidates, or even kick out the bums in power, sits uneasily with the combination of untrammelled redistricting power and predictable political preferences that characterise the US today. But if it is so easy for mapmakers to vitiate the democratic purpose of elections in single-member districts, doesn’t neutrality demand some constraint on the ability of incumbents to choose voters, rather than the other way round?

After the Texas redistricting, Roberts’s belief that neutrality requires inaction appears even shakier. By adding five seats to the expected Texan Republican delegation, the Republican Party improves the odds it will retain, or even increase, its six-seat majority in the House in November 2026. Even a slight advantage gained through redistricting may have national implications because the Democrats’ lead in the polls is consistently small (around two points). Congressional maps are usually redrawn once every ten years, after each decennial census (the next one is in 2030). Mid-cycle redistricting does sometimes happen – Texas did the same thing two decades ago – but it is unusual. So is Trump’s open embrace of gerrymanders. In 1891, Benjamin Harrison condemned gerrymandering as ‘political robbery’. Sixty years later, Harry Truman called for federal legislation to end its use; a bill was introduced in the House but died in the Senate. In 1987, Ronald Reagan told a meeting of Republican governors that gerrymanders were ‘corrupt’. (...)

King and Hunter can say these things because there is no judicial remedy for designing a redistricting map that sews up the outcome of a congressional election. In 2019, Chief Justice John Roberts declared that although the Supreme Court ‘does not condone excessive partisan gerrymandering’, any court-mandated intervention in district maps would inevitably look partisan and impugn the court’s neutrality. In 2017, during arguments in a different case, Roberts contrasted the ‘sociological gobbledygook’ of political science on gerrymandering with the formal and objective science of American constitutional law.

‘Sociological gobbledygook’ teaches that the drawing of the boundaries of single-member districts can all but determine the outcome of an election. Imagine a state with twenty blue and thirty red voters that must be sliced into five districts. A map that tracked the overall distribution of votes would have two blue and three red districts. But if you can put six red voters and four blue voters in each of the five boxes, you will end up with five relatively safe red districts. This is known as ‘cracking’ the blue electorate. Or you could create two districts with six blues and one with eight blues, making three safe blue districts by ‘packing’ red supporters – concentrating them in a smaller number of districts. The notion that democratic elections are supposed to allow voters to make a real choice between candidates, or even kick out the bums in power, sits uneasily with the combination of untrammelled redistricting power and predictable political preferences that characterise the US today. But if it is so easy for mapmakers to vitiate the democratic purpose of elections in single-member districts, doesn’t neutrality demand some constraint on the ability of incumbents to choose voters, rather than the other way round?

After the Texas redistricting, Roberts’s belief that neutrality requires inaction appears even shakier. By adding five seats to the expected Texan Republican delegation, the Republican Party improves the odds it will retain, or even increase, its six-seat majority in the House in November 2026. Even a slight advantage gained through redistricting may have national implications because the Democrats’ lead in the polls is consistently small (around two points). Congressional maps are usually redrawn once every ten years, after each decennial census (the next one is in 2030). Mid-cycle redistricting does sometimes happen – Texas did the same thing two decades ago – but it is unusual. So is Trump’s open embrace of gerrymanders. In 1891, Benjamin Harrison condemned gerrymandering as ‘political robbery’. Sixty years later, Harry Truman called for federal legislation to end its use; a bill was introduced in the House but died in the Senate. In 1987, Ronald Reagan told a meeting of Republican governors that gerrymanders were ‘corrupt’. (...)

Democratic states have threatened to retaliate. In California, Governor Gavin Newsom has scheduled a special election on Proposition 50, which would temporarily suspend the state’s independent redistricting commission, making it possible for the Democratic legislature to flip five Republican seats (43 of California’s 52 seats are held by Democrats). Like California, New York has a bipartisan commission, which usually redraws its maps once a decade. The Democrats have brought in legislation allowing mid-decade changes, but new maps won’t be in place until 2028. Democrats who used to be fierce advocates of independent commissions are now asking themselves whether they’ve been too slow to fight back. From a party that has a habit of bringing a knife to a gunfight, the question answers itself.

In the late 20th century, there were only ten seats nationally that repeatedly changed hands as a result of partisan gerrymandering, with control of the House flipping on just one occasion, in 1954. But in 2012, Republicans started to change this. Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Virginia were all sliced up. The increase in gerrymanders was in part a result of Redmap, the Redistricting Majority Project, a Republican initiative set up in 2010 which invested in the races for the state legislatures, such as Texas’s, tasked with drawing district maps. In 1981, Democrats controlled the mapmaking process in 164 seats, while Republicans controlled it in 50. By 2021, the Republicans controlled line-drawing for 187 seats, the Democrats 49. At the same time, computers had made it cheaper and easier to design maps optimising one party’s performance without breaking the legal constraints on redistricting, such as the Voting Rights Act and the prohibition on districts drawn on the basis of race. In the 1980s, it cost $75,000 to buy software to do this; by the early 2000s, programs such as Maptitude for Redistricting cost $3000.

Just as in the late 19th century, urbanisation is now producing new political geography: migration from Democrat-leaning states such as California, New York, Pennsylvania and Illinois means they will lose House seats after the 2030 census. Meanwhile, Texas, Florida, Georgia and North Carolina, all of which lean Republican, are set to gain seats. Texas’s gerrymander, in other words, foreshadows a change in national political power that is coming anyway.

by Azia Huq, London Review of Books | Read more:

Image: The Ninth Congressional District in Texas, before and after this year’s remapping.In the late 20th century, there were only ten seats nationally that repeatedly changed hands as a result of partisan gerrymandering, with control of the House flipping on just one occasion, in 1954. But in 2012, Republicans started to change this. Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Virginia were all sliced up. The increase in gerrymanders was in part a result of Redmap, the Redistricting Majority Project, a Republican initiative set up in 2010 which invested in the races for the state legislatures, such as Texas’s, tasked with drawing district maps. In 1981, Democrats controlled the mapmaking process in 164 seats, while Republicans controlled it in 50. By 2021, the Republicans controlled line-drawing for 187 seats, the Democrats 49. At the same time, computers had made it cheaper and easier to design maps optimising one party’s performance without breaking the legal constraints on redistricting, such as the Voting Rights Act and the prohibition on districts drawn on the basis of race. In the 1980s, it cost $75,000 to buy software to do this; by the early 2000s, programs such as Maptitude for Redistricting cost $3000.

Just as in the late 19th century, urbanisation is now producing new political geography: migration from Democrat-leaning states such as California, New York, Pennsylvania and Illinois means they will lose House seats after the 2030 census. Meanwhile, Texas, Florida, Georgia and North Carolina, all of which lean Republican, are set to gain seats. Texas’s gerrymander, in other words, foreshadows a change in national political power that is coming anyway.

by Azia Huq, London Review of Books | Read more:

[ed. If you can't win fair and square, cheat. It looks almost certain that all national elections going forward will be a nightmare.]

Biologists Announce There Absolutely Nothing We Can Learn From Clams

WOODS HOLE, MA—Saying they saw no conceivable reason to bother with the bivalve mollusks, biologists at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution announced Thursday that there was absolutely nothing to be learned from clams. “Our studies have found that while some of their shells look pretty cool, clams really don’t have anything to teach us,” said the organization’s chief scientist, Francis Dawkins, clarifying that it wasn’t simply the case that researchers had already learned everything they could from clams, but rather that there had never been anything to learn from them and never would be. “We certainly can’t teach them anything. It’s not like you can train them to run through a maze the way you would with mice. We’ve tried, and they pretty much just lie there. From what I’ve observed, they have a lot more in common with rocks than they do with us. They’re technically alive, I guess, if you want to call that living. They open and close sometimes, but, I mean, so does a wallet. If you’ve used a wallet, you know more or less all there is to know about clams. Pretty boring.” The finding follows a study conducted by marine biologists last summer that concluded clams don’t have much flavor, either, tasting pretty much the same as everything else on a fried seafood platter.

by The Onion | Read more:

Image: uncredited

A photograph by Berenice Abbott of an unidentified engineer wiring a computer made by IBM in the late 1950s, MIT, 1961. This image was part of the exhibition Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960–1991, which was on view last winter at Madam Luxembourg and during the spring Kunsthalle Wien, in Vienna.The catalog was published this month by D.A.P. Courtesy D.A.P.

America's Future Could Hinge on Whether AI Slightly Disappoints

A burning question that’s on a lot of people’s minds right now is: Why is the U.S. economy still holding up? The manufacturing industry is hurting badly from Trump’s tariffs, the payroll numbers are looking weak, and consumer sentiment is at Great Recession levels:

And yet despite those warning signs, there has been nothing even remotely resembling an economic crash yet. Unemployment is rising a little bit but still extremely low, while the prime-age employment rate — my favorite single indicator of the health of the labor market — is still near all-time highs. The New York Fed’s GDP nowcast thinks that GDP growth is currently running at a little over 2%, while the Atlanta Fed’s nowcast puts it even higher.

One possibility is that everything is just fine with the economy — that Trump’s tariffs aren’t actually that high because of all the exemptions, and/or that economists are exaggerating the negative effects of tariffs in the first place. Weak consumer confidence could be a partisan “vibecession”, payroll slowdown could be from illegal immigrants being deported or leaving en masse, and manufacturing’s woes could be from some other sector-specific factor.

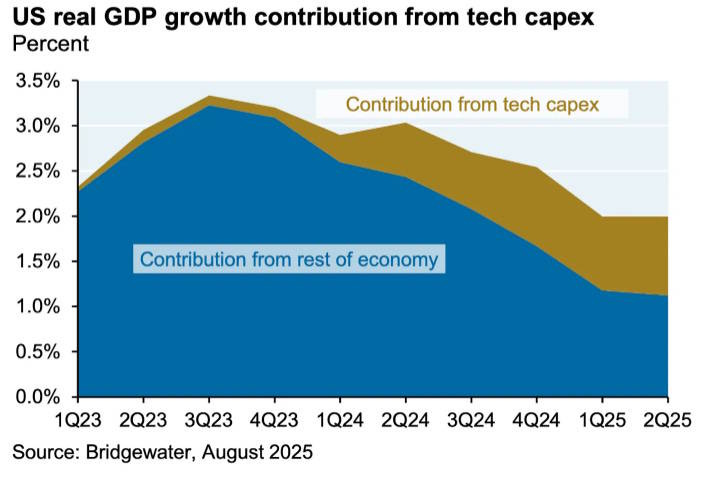

Another possibility is that tariffs are bad, but are being canceled out by an even more powerful force — the AI boom. The FT reports:

Pantheon Macroeconomics estimates that US GDP would have grown at a mere 0.6 per cent annualised rate in the first half were it not for AI-related spending, or half the actual rate.

Paul Kedrosky came up with similar numbers. Jason Furman does a slightly different calculation, and arrives at an even starker number: [ed. 0.1 percent]

And here’s an impressive chart:

The Economist writes:

Now as Furman points out, this doesn’t necessarily mean that without AI, the U.S. economy would be stalling out. If the economy wasn’t pouring resources into AI, it might be pouring them into something else, spurring growth that was almost as fast as what we actually saw. But it’s also possible that without AI, America would be crashing from tariffs. (...)

But despite Trump’s tariff exemptions, the AI sector could very well crash in the next year or two. And if it does, it could do a lot more than just hurt Americans’ employment prospects and stock portfolios.

If AI is really the only thing protecting America from the scourge of Trump’s tariffs, then a bust in the sector could change the country’s entire political economy. A crash and recession would immediately flip the narrative on Trump’s whole presidency, much as the housing crash of 2008 cemented George W. Bush’s legacy as a failure. And because Trump’s second term is looking so transformative, the fate of the AI sector could potentially determine the entire fate of the country.

And yet despite those warning signs, there has been nothing even remotely resembling an economic crash yet. Unemployment is rising a little bit but still extremely low, while the prime-age employment rate — my favorite single indicator of the health of the labor market — is still near all-time highs. The New York Fed’s GDP nowcast thinks that GDP growth is currently running at a little over 2%, while the Atlanta Fed’s nowcast puts it even higher.

One possibility is that everything is just fine with the economy — that Trump’s tariffs aren’t actually that high because of all the exemptions, and/or that economists are exaggerating the negative effects of tariffs in the first place. Weak consumer confidence could be a partisan “vibecession”, payroll slowdown could be from illegal immigrants being deported or leaving en masse, and manufacturing’s woes could be from some other sector-specific factor.

Another possibility is that tariffs are bad, but are being canceled out by an even more powerful force — the AI boom. The FT reports:

Pantheon Macroeconomics estimates that US GDP would have grown at a mere 0.6 per cent annualised rate in the first half were it not for AI-related spending, or half the actual rate.

Paul Kedrosky came up with similar numbers. Jason Furman does a slightly different calculation, and arrives at an even starker number: [ed. 0.1 percent]

And here’s an impressive chart:

The Economist writes:

[L]ook beyond AI and much of the economy appears sluggish. Real consumption has flatlined since December. Jobs growth is weak. Housebuilding has slumped, as has business investment in non-AI parts of the economy[.]And in a post entitled “America is now one big bet on AI”, Ruchir Sharma writes that “AI companies have accounted for 80 per cent of the gains in US stocks so far in 2025.” In fact, more than a fifth of the entire S&P 500 market cap is now just three companies — Nvidia, Microsoft, and Apple — two of which are basically big bets on AI.

Now as Furman points out, this doesn’t necessarily mean that without AI, the U.S. economy would be stalling out. If the economy wasn’t pouring resources into AI, it might be pouring them into something else, spurring growth that was almost as fast as what we actually saw. But it’s also possible that without AI, America would be crashing from tariffs. (...)

But despite Trump’s tariff exemptions, the AI sector could very well crash in the next year or two. And if it does, it could do a lot more than just hurt Americans’ employment prospects and stock portfolios.

If AI is really the only thing protecting America from the scourge of Trump’s tariffs, then a bust in the sector could change the country’s entire political economy. A crash and recession would immediately flip the narrative on Trump’s whole presidency, much as the housing crash of 2008 cemented George W. Bush’s legacy as a failure. And because Trump’s second term is looking so transformative, the fate of the AI sector could potentially determine the entire fate of the country.

by Noah Smith, Noahpinion | Read more:

Image: Derek Thompson/Bridgewater

No Kings Day - October 18, 2025

The president has tried to leverage the power of the federal government against his political opponents and legal adversaries, sending the Justice Department after James Comey, a former director of the F.B.I.; Attorney General Letitia James of New York; and one of Trump’s former national security advisers, John Bolton. Trump also wants to use the I.R.S. and other agencies to harass liberal donors and left-leaning foundations. He has even tried to revive lèse-majesté, threatening critics of his administration and its allies with legal and political sanctions. With Trump, it’s as if you crossed the bitter paranoia of Richard Nixon with the absolutist ideology of Charles I.

Today’s protesters, in other words, are standing for nothing less than the anti-royal and republican foundations of American democracy. For the leaders of the Republican Party, however, these aren’t citizens exercising their fundamental right to dissent but subversives out to undermine the fabric of the nation.

Senator John Barrasso of Wyoming said of a planned No Kings protest that it would be a “big ‘I hate America’ rally” of “far-left activist groups.” House Majority Leader Steve Scalise of Louisiana also called No Kings a “hate America rally.” House Speaker Mike Johnson told reporters that he expected to see “Hamas supporters,” “antifa types” and “Marxists” on “full display.” People, he said without a touch of irony, “who don’t want to stand and defend the foundational truths of this republic.” And all of this is of a piece with the recent declaration by the White House press secretary, Karoline Leavitt, that “the Democrat Party’s main constituency is made up of Hamas terrorists, illegal aliens and violent criminals.”

This, I should think, is news to the Democratic Party.

... much of Trump’s effort to extend his authority across the whole of American society depends on more or less voluntary compliance from civil society and various institutions outside of government. And that, in turn, rests on the idea that Trump is the authentic tribune of the people. Reject Trump, and you reject the people, who may then turn on your business or your university or, well, you.

Nationwide protests comprised of millions of people are a direct rebuke to the president’s narrative. They send a signal to the most disconnected parts of the American public that the president is far from as popular as he says he is, and they send a clear warning to those institutions under pressure from the administration: Bend the knee and lose our business and support.

Nationwide protests comprised of millions of people are a direct rebuke to the president’s narrative. They send a signal to the most disconnected parts of the American public that the president is far from as popular as he says he is, and they send a clear warning to those institutions under pressure from the administration: Bend the knee and lose our business and support.

by Jamelle Bouie, NY Times | Read more:

Images: markk

[ed. So proud of my little (red) town. Over 1500 patriots coming together in support of democracy and a United States for All. America will never be great again if we continue to let one administration, one party, one media channel, and a slew of billionaire elitists divide us. China and other adversaries will only get stronger while we're busy shooting ourselves in the foot. For example: America could win this trade war if it wanted to (Noahpinion):]

***

China has unveiled broad new curbs on its exports of rare earths and other critical materials…Overseas exporters of items that use even traces of certain rare earths sourced from China will now need an export license…Certain equipment and technology for processing rare earths and making magnets will also be subject to controls…[China] later announced plans to expand export controls to a range of new products…[these] five more rare earths — holmium, europium, ytterbium, thulium, erbium — plus certain lithium-ion batteries, graphite anodes and synthetic diamonds, as well as some equipment for making those materials.Trump immediately responded with bellowing bravado, announcing new 100% tariffs on Chinese goods, as well as various new export controls. Trump’s treasury secretary, Scott Bessent, joined in, calling China’s trade negotiators “unhinged”.

But just a few days later, Trump and Bessent were already backing down in the face of China’s threats. Trump admitted that 100% tariffs on China were “not sustainable”, and declared that “[W]e’re doing very well. I think we’re getting along with China.” Bessent offered a “truce” in which the U.S. suspends tariffs on China in exchange for China suspending its threat of export controls.

The most likely outcome, therefore, is that China simply wins this round of the trade war, as it won the last round. In April, Trump announced big tariffs on China. China retaliated by implementing rare earth export controls, causing Trump to back down and reduce tariffs to a low level. But China didn’t reciprocate — it kept its export controls in place, allowing America to keep buying rare earths only through some short-term conditional arrangements. China then used these controls to extract even more concessions from the hapless Americans: (...)

This was also entirely consistent with the pattern of Trump’s first term, in which he agreed to suspend planned tariffs on China in exchange for empty promises of agricultural purchases that China never ended up keeping. It fit the common caricature of Trump as a cowardly bully who acts with extreme aggression toward weak opponents, but who retreats from any rival who stands up and hits back.

If the pattern holds this time, then Trump will retreat from his threats of sky-high tariffs, but China will keep its new export controls in place. Lingling Wei and Gavin Bade report that China’s leaders believe they have the American President over a barrel: (...)