Matt Taibbi’s Hate Inc. is the most insightful and revelatory book about American politics to appear since the publication of Thomas Frank’s Listen, Liberal almost four full years ago, near the beginning of the last presidential election cycle.

While Frank’s topic was the abysmal failure of the Democratic Party to be democratic and Taibbi’s is the abysmal failure of our mainstream news corporations to report news, the prominent villains in both books are drawn from the same, or at least overlapping, elite social circles: from, that is, our virulently anti-populist

liberal class, from our intellectually mediocre

creative class, from our bubble-dwelling

thinking class. In fact, I would strongly recommend that the reader spend some time with Frank’s

What’s the Matter with Kansas? (2004) and

Listen, Liberal! (2016) as he or she takes up Taibbi’s book. And to really do the book the justice it deserves, I would even more vehemently recommend that the reader immerse him- or herself in Taibbi’s favorite book and

vade-mecum, Manufacturing Consent (which I found to be a grueling experience: a relentless cataloging of the official lies that hide the brutality of American foreign policy) and, in order to properly appreciate the brilliance of Taibbi’s chapter 7, “How the Media Stole from Pro Wrestling,” visit some locale in Flyover Country and see some pro wrestling in person (which I found to be unexpectedly uplifting — more on this soon enough).

Taibbi tells us that he had originally intended for

Hate, Inc. to be an updating of Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky’s

Manufacturing Consent (1988), which he first read thirty years ago, when he was nineteen. “It blew my mind,” Taibbi writes. “[It] taught me that some level of deception was baked into almost everything I’d ever been taught about modern American life…. Once the authors in the first chapter laid out their famed

propaganda model [italics mine], they cut through the deceptions of the American state like a buzz saw” (p. 10). For what seemed to be vigorous democratic debate, Taibbi realized, was instead a soul-crushing simulation of debate. The choices voters were given were distinctions without valid differences, and just as hyped, just as trivial, as the choices between a Whopper and a Big Mac, between Froot Loops and Frosted Mini-Wheats, between Diet Coke and Diet Pepsi, between Marlboro Lites and Camel Filters. It was all profit-making poisonous junk.

“

Manufacturing Consent,” Taibbi writes, “explains that the debate you’re watching is choreographed. The range of argument has been artificially narrowed long before you get to hear it” (p. 11). And there’s an indisputable logic at work here, because the reality of hideous American war crimes is and always has been, from the point of view of the big media corporations, a “narrative-ruining” buzz-kill. “The uglier truth [brought to light in

Manufacturing Consent], that we committed genocide of a fairly massive scale across Indochina — ultimately killing at least a million innocent civilians by air in three countries — is pre-excluded from the history of the period” (p. 13).

So what has changed in the last thirty years? A lot! As a starting point let’s consider the very useful metaphor found in the title of another great media book of 1988: Mark Crispin Miller’s

Boxed In: The Culture of TV. To say that Americans were held captive by the boob tube affords us not only a useful historical image but also suggests the possibility of their having been able to view the television as an antagonist, and therefore of their having been able, at least some of them, to rebel against its dictates. Three decades later, on the other hand, the television has been replaced by iPhones and portable tablets, the workings of which are so precisely intertwined with even the most intimate minute-to-minute aspects of our lives that our relationship to them could hardly ever become antagonistic.

Taibbi summarizes the history of these three decades in terms of three “massive revolutions” in the media plus one actual massive political revolution, all of which, we should note, he discussed with his hero Chomsky (who is now ninety! — Edward Herman passed away in 2017) even as he wrote his book. And so: the media revolutions which Taibbi describes were, first, the coming of FoxNews along with Rush Limbaugh-style talk radio; second, the coming of CNN, i.e., the Cable News Network, along with twenty-four hour infinite-loop news cycles; third, the coming of the Internet along with the mighty social media giants Facebook and Twitter. The massive political revolution was, going all the way back to 1989, the collapse of the Berlin Wall, and then of the Soviet Union itself — and thus of the usefulness of anti-communism as a kind of coercive secular religion (pp. 14-15).

For all that, however, the most salient difference between the news media of 1989 and the news media of 2019 is the disappearance of the single type of calm and decorous and slightly boring cis-het white anchorman (who somehow successfully appealed to a nationwide audience) and his replacement by a seemingly wide variety of demographically-engineered news personæ who all rage and scream combatively in each other’s direction. “In the old days,” Taibbi writes, “the news was a mix of this toothless trivia and cheery dispatches from the frontlines of Pax Americana…. The news [was] once designed to be consumed by the whole house…. But once we started to be organized into

demographic silos [italics mine], the networks found another way to seduce these audiences: they sold intramural conflict” (p. 18).

And in this new media environment of constant conflict, how, Taibbi wondered, could public

consent, which would seem to be at the opposite end of the spectrum from conflict, still be

manufactured?? “That wasn’t easy for me to see in my first decades in the business,” Taibbi writes. “For a long time, I thought it was a flaw in the Chomsky/Herman model” (p. 19).

But what Taibbi was at length able to understand, and what he is now able to describe for us with both wit and controlled outrage, is that our corporate media have devised — at least for the time being — highly-profitable marketing processes that manufacture

fake dissent in order to smother

real dissent (p. 21). And the smothering of real dissent is close enough to public

consent to get the goddam job done: The Herman/Chomsky model is, after all these years, still valid.

Or pretty much so. Taibbi is more historically precise. Because of the tweaking of the Herman/Chomsky propaganda model necessitated by the disappearance of the USSR in 1991 (“The Russians escaped while we weren’t watching them, / As Russians do…,” Jackson Browne presciently prophesied on MTV way back in 1983), one might now want to speak of a Propaganda Model 2.0. For, as Taibbi notes, “…the biggest change to Chomsky’s model is the discovery of a far superior ‘common enemy’ in modern media: each other. So long as we remain a bitterly-divided two-party state, we’ll never want for TV villains” (pp. 207-208).

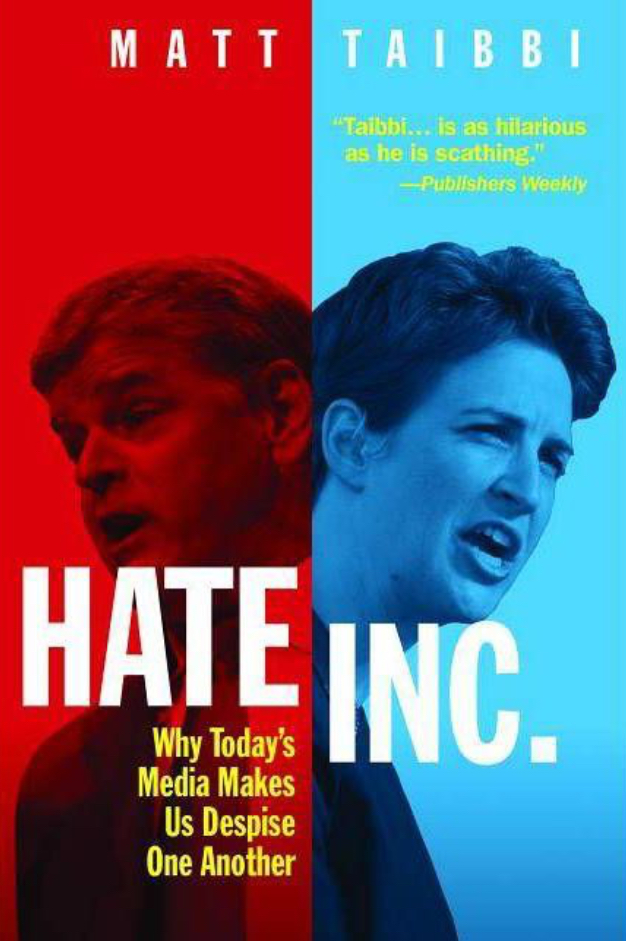

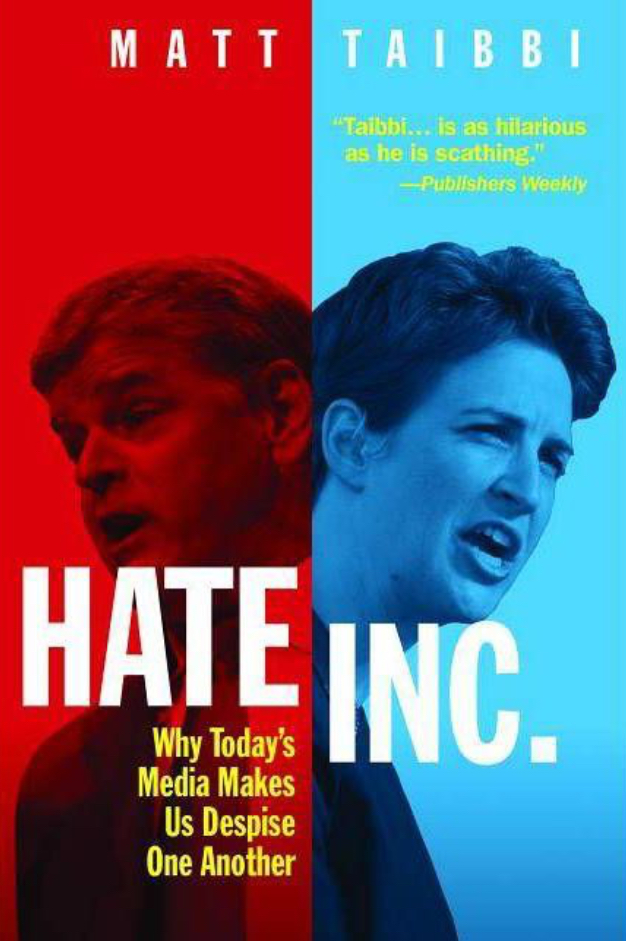

To rub his great insight right into our uncomprehending faces, Taibbi has almost sadistically chosen to have dark, shadowy images of a yelling Sean Hannity (in lurid FoxNews Red!) and a screaming Rachel Maddow (in glaring MSNBC Blue!) juxtaposed on the cover of his book. For Maddow, he notes, is “a depressingly exact mirror of Hannity…. The two characters do exactly the same work. They make their money using exactly the same commercial formula. And though they emphasize different political ideas, the effect they have on audiences is much the same” (pp. 259-260).

And that effect is hate. Impotent hate. For while Rachel’s fan demographic is all wrapped up in hating Far-Right Fascists Like Sean, and while Sean’s is all wrapped up in despising Libtard Lunatics Like Rachel, the bipartisan consensus in Washington for ever-increasing military budgets, for everlasting wars, for ever-expanding surveillance, for ever-growing bailouts of and tax breaks for and and handouts to the most powerful corporations goes forever unchallenged.

Oh my. And it only gets worse and worse, because the media, in order to make sure that their various

siloed demographics stay superglued to their Internet devices, must keep ratcheting up levels of hate: the Fascists Like Sean and the Libtards Like Rachel must be continually presented as more and more deranged, and ultimately as demonic. “There is us and them,” Taibbi writes, “and they are Hitler” (p. 64). A vile

reductio ad absurdum has come into play: “If all Trump supporters are Hitler, and all liberals are also Hitler,” Taibbi writes, “…[t]he

America vs. America show is now

Hitler vs. Hitler! Think of the ratings!…” The reader begins to grasp Taibbi’s argument that our mainstream corporate media are as bad as — are worse than — pro wrestling. It’s an ineluctable downward spiral.

Taibbi continues: “The problem is, there’s no natural floor to this behavior. Just as cable TV will eventually become seven hundred separate twenty-four-hour porn channels, news and commentary will eventually escalate to boxing-style, expletive-laden, pre-fight tirades, and

the open incitement to violence [italics mine]. If the other side is literally Hitler, … [w]hat began as

America vs. America will eventually move to

Traitor vs. Traitor, and the show does not work if those contestants are not eventually offended to the point of wanting to kill one another” (pp. 65-69). (...)

On the same day I read this chapter I saw that, on the bulletin board in my gym, a poster had appeared, as if by magic, promoting an upcoming

Primal Conflict (!) professional wrestling event. I studied the photos of the wrestlers on the poster carefully, and, as an astute reader of Taibbi, I prided myself on being able to identify which of them seemed be playing the roles of

heels, and which of them the roles of

babyfaces.

For Taibbi explains that one of the fundamental dynamics of wrestling involves the invention of crowd-pleasing narratives out of the many permutations and combinations of pitting

heels against

faces. Donald Trump, a natural

heel, brings the goofy dynamics of pro wrestling to American politics with real-life professional expertise. (Taibbi points out that in 2007 Trump actually performed before a huge cheering crowd in a

Wrestlemania event billed as the “battle of the billionaires.” Watch it on YouTube!

https://youtu.be/5NsrwH9I9vE— unbelievable!!)

The mainstream corporate media, on the other hand, their eyes fixed on ever bigger and bigger profits, have drifted into the metaphorical pro wrestling ring in ignorance, and so, when they face off against Trump, they often end up in the role of inept prudish pearl-clutching faces.

Taibbi condemns the mainstream media’s failure to understand such a massively popular form of American entertainment as “malpractice” (p. 125), so I felt more than obligated to buy a ticket and see the advertised event in person. To properly educate myself, that is.

On the poster in my gym I had paid particular attention to the photo of character named

Logan Easton Laroux, who was wearing a sweater tied around his neck and was extending an index finger upwards as if he were summoning a waiter. Ha! I thought. This Laroux chap must be playing the role of an arrogant preppy

face. The crowd will delight in his humiliation! I imagined the vile homophobic and even Francophobic abuse to which he would likely be subjected.

On the night of the Primal Conflict event, I intentionally showed up a little bit late, because, to be honest, I was fearing a rough crowd. Pro wrestling in West Virginia, don’t you know. But I was politely greeted and presented with the ticket I had PayPal-ed. I looked over to the ring, and, sure enough, there was

Logan Easton Laroux being body-slammed to the mat. Ha! Just the ritual humiliation I anticipated! But I had most certainly not anticipated the sudden display of Primal Conflict wit that ensued. Our plucky Laroux dramatically recovered from his fall and adroitly pinned his opponent as the crowd happily cheered for him, cheered in unison, cheered an apparently rehearsed chant again and again:

ONE PER CENT! ONE PER CENT!

So no homophobic obscenities??

Au contraire! Here was a twist in narrative far more nuanced than anything you might read in the

New York Times!

Soon enough I realized that this was

wholesome family entertainment. The most enthusiastic fans seemed to be the eight- and nine-year-old boys. (A couple of the boys were proudly wearing their Halloween costumes.) There was no smoking, no drinking, no foul language, no sexual innuendo of any sort, and, above all no racial insults — just the opposite: For both the wrestlers and the spectators were a mix of white and black, and the most popular wrestler was a big black guy in an afro wig who “lost” his bout to a white guy who played a cheating sleazebag

heel named Quinn. Also, significantly, there was zero police presence, and zero chance of any kind of actual altercation. When the night was over the promoter stood at the exit and shook the hand of and said good-bye and come-back to each of us departing spectators — sort of like, well, a pastor after church in a small southern town as his congregation disperses.

So here I was in the very midst of — to use Hillary Clinton’s contemptuous terminology—

the deplorables. But they weren’t the racist misogynistic homophobes Clinton had condemned. The vibe was that everyone liked all the wrestlers, even the ones they had booed, and that everyone pretty much liked each other. During intermission the promoter called out a birthday greeting to a spectator named John. A middle-aged black guy stood up to a round of applause. He was with his wife and kids.

Where was the hate?

by Yves Smith, Naked Capitalism |

Read more:

Image: OR Books

[ed. See also:

Is Politics a War of Ideas or of Us Against Them? (NY Times)]

It has become one of the peculiar features of the NFL calendar since both the Chargers and Rams relocated to Los Angeles in 2017, marking a reunion between America’s second-largest market and its most popular sporting league: more often than not, the teams’ home games look and sound like home games for the opposition. Chargers players were showered with boos when they took the field against the visiting Philadelphia Eagles two years ago. The Rams got the same treatment last season at home against the Packers. Both Rivers, the Chargers quarterback, and Rams quarterback Jared Goff have regularly been forced to use a silent count to combat the noise generated by the away side’s fans, typically an unnecessary measure to take for a team playing at home.

It has become one of the peculiar features of the NFL calendar since both the Chargers and Rams relocated to Los Angeles in 2017, marking a reunion between America’s second-largest market and its most popular sporting league: more often than not, the teams’ home games look and sound like home games for the opposition. Chargers players were showered with boos when they took the field against the visiting Philadelphia Eagles two years ago. The Rams got the same treatment last season at home against the Packers. Both Rivers, the Chargers quarterback, and Rams quarterback Jared Goff have regularly been forced to use a silent count to combat the noise generated by the away side’s fans, typically an unnecessary measure to take for a team playing at home.